The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| II. |

| II. 1. |

| II. 2. |

| II. 3. |

| II.3.1. |

| II.3.2. |

| II.3.3. |

| II.3.4. |

| II.3.5. |

| II.3.6. |

| II.3.7. |

| II.3.8. |

| II.3.9. |

| II.3.10. |

MEDITERRANEAN OR NORTHERN ROOTS:

A DIVISION OF MINDS |

| III. |

| IV. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

MEDITERRANEAN OR NORTHERN ROOTS:

A DIVISION OF MINDS

Because of its geographical distribution primarily in the

territory of the Franks, Saxons, and Normans, Georg

Dehio considered the square schematism to be essentially

a "Germanic" contribution.[288]

Samuel Guyer,[289]

in a complete

reversal of this contention declared this "geometrical

clarity" to be a mark "of the Mediterranean way of thinking,"

and "one that had its roots in classical antiquity."[290]

The square schematism of the Plan of St. Gall, he maintained,

was not one of the new and creative contributions

to medieval architecture that it had been assumed to be,

but "transmits to the West in a rather muddled manner the

thought of the qualitatively superior art" of the Early

Christian period.[291]

These statements are of questionable historical validity—

and the argument does not gain in power when one finds it

supported by such sweeping generalities as "A civilization

in process of just awakening from the darkness of an

a-historical past" and "as yet suspended in a state of

unstable hovering between unconsciousness and awakeness"

could not possibly have produced aesthetic concepts

"of such distinct and clear rationality. . . . The period of

Charlemagne had never the significance ascribed to it so

fervently in recent times. . . . In the time of Emperor

Charlemagne the thoughts of Late Antiquity and Early

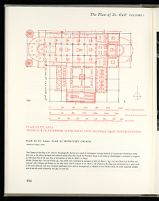

173. PLAN OF ST. GALL. PLAN OF MONASTERY CHURCH

SHOWN AT SCALE 1:600

The Church of the Plan of St. Gall is chronologically the last of a triad of Carolingian transept basilicas of monumental dimensions owing

their size to the tide of spiritual and cultural exhilaration that seized the Frankish clergy in the wake of Charlemagne's coronation as emperor,

on Christmas Eve of the year 800, in the basilica of Old St. Peter's in Rome.

Unlike Cologne (fig. 172) and Fulda (fig. 169) which were occidented in imitation of Old St. Peter's, (fig. 170) the Church of the Plan was

oriented. Like Cologne and Fulda, on the other hand, and in contrast to St. Peter's, the Church of the Plan was constructed on a square grid,

in the most elaborate and most consistent application of it, since it encompassed, in addition to the Church itself, the entire claustral complex

and in fact the entire monastery site (figs. 62 and 63).

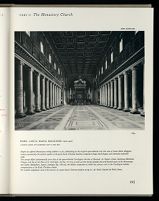

174. ROME. SANTA MARIA MAGGIORE (432-440)

LOOKING NORTH AND SOMEWHAT EAST TO THE APSE

Despite its coffered Renaissance ceiling (added in 1500, substituting for the original open-timbered roof) this view of Santa Maria Maggiore

conveys persuasively the stylistic quality of the great Early Christian basilicas composed of huge, block-shaped, and internally undivided

voids.

The concept differs fundamentally from that of the square-divided Carolingian churches of Neustadt, St. Riquier, Fulda, Reichenau-Mittelzell,

Cologne, and that of the Plan of St. Gall (figs. 167-69; 171-73), as well as from the bay-divided and arch-framed spaces of the Romanesque

and Gothic (Hildesheim, Speyer, Jumièges; figs. 188-90), the cellular composition of which has primary roots in the Carolingian modular

reorganization of the Early Christian scheme.

For another magnificent view of the interior of a great Early Christian basilica see fig. 81, St. Paul's Outside the Walls, Rome.

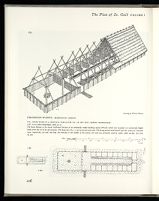

175. FEDDERSEN-WIERDE, BREMERHAVEN, GERMANY

175: AISLED HOUSE OF A CHIEFTAIN, WARF-LAYER 11B, 1ST-2ND CENT. (authors' reconstruction)

176: PLAN (after Haarnagel, 1956, pl. 3)

The house belongs to the second settlement horizon of an artificially raised dwelling mound (Warf) which was occupied, on successively higher

levels, from the 1st to the 4th centuries. The house was 28.5 × 7.5m on an east-west axis. The living portion with hearth and the section for livestock

were, respectively, 9m and 16m long. An entrance in the middle of the eastern end wall was primarily used by cattle. (Also see figs. 315-316, II, 58.)

to be incapable of taking any deep root or of being developed

any further."[292]

I propose that we confine ourselves to specific issues

rather than argue the case in such global terms.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||