The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| II. |

| II. 1. |

| II. 2. |

| II. 3. |

| II.3.1. |

| II.3.2. |

| II.3.3. |

| II.3.4. |

| II.3.5. |

| II.3.6. |

| II.3.7. |

| II.3.8. |

| II.3.9. |

| II.3.10. | II.3.10 |

| III. |

| IV. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

II.3.10

SQUARE SCHEMATISM

"Square schematism" is a principle of medieval church

design by which the constituent spaces of the church are

calculated as multiples of a basic spatial unit, usually that

of the crossing square. The origin and evolution of this

concept is still one of the great mysteries of medieval

architectural history. The Church of the Plan of St. Gall

represents a crucial stage in the conceptual development of

this principle. The importance of this fact has been blurred

because no consensus of opinion had been obtained, in

previous inquiries, with regard to even the simple question

of whether or not the design of the Church of the Plan had,

in fact, been developed within a system of squares; let alone

the infinitely more complex problem of the historical roots

and the deeper cultural significance of this fascinating

principle of articulating space. I, for one, am convinced

that these questions cannot be solved from within the

field of architectural history. The modular mode of thinking

that underlies this schematism is a general cultural

phenomenon that manifests itself in other spheres of life.

On the following pages I shall try to isolate some of the

converging historical currents that merge in this concept.

PRESENCE OR ABSENCE OF THE GRID OF SQUARES

On the Plan of St. Gall the square and the grid of squares

are used in two different ways: as a method of mensuration,

and as an aesthetic principle. In the first instance the square

grid offered a convenient method of dividing a given area

internally by defining it as a multiple or fraction of certain

modular master units (2½-foot square, 40-foot square, 160foot

square).[282]

In the other case, the square grid was used

as an active principle of architectural composition. It is this

latter type alone with which we are now concerned. Reinhardt

categorically denied its presence on the Plan of St.

Gall.[283]

Similar views were expressed in 1945 by Samuel

Guyer,[284]

but convincingly challenged in 1952 by Albert

Knoepfli[285]

in a drawing which shows a grid of 10-foot

squares superimposed upon the Plan of the Church.[286]

My

own analysis of the scale and construction methods used in

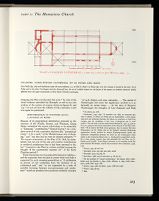

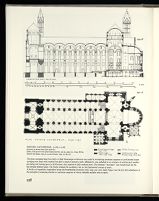

172. COLOGNE. CAROLINGIAN CATHEDRAL OF SS PETER AND MARY

Like Fulda (fig. 169) and doubtlessly under the same influence, i.e., of Old St. Peter's in Rome (fig. 170), the transept is located in the west. As in

Fulda and in the other Carolingian churches discussed here, the use of modules imparts to the layout of the spaces an aesthetic character wholly

different from the squat corporeality of their Early Christian prototypes.

visual evidence submitted by Knoepfli, as well as my own

analysis of the system of squares shown in figures 61 and

173, I do not see how the validity of this contention could

ever again be questioned.

Reinhardt, 1937, 269: "A première vue, déjà, on reconnait que,

dans le dessin, le choeur ne forme pas un quadrilatère a côtés égaux,

mais qu'il est nettement barlong. De même, on constatera, a l'aide d'un

compas, que les croisillons, à leur tour, n'attaignent pas le carré

parfait." On the basis of these observations Reinhardt, 1952, 25, goes so

far as to question the entire schematism of the Church of the Plan of St.

Gall: "Es is bereits die Rede davon gewesen, dass in neuerer Zeit dem

Klosterplan von St. Gallen eine in die Zukunft weisende Bedeutung

zugemessen wurde, insofern in seinem Kirchengrundriss bereits die

Quadratur massgeblich gewesen sei sowie sie erst zweihundert Jahre

später in den deutschen Bauten des 11. Jahrhunderts ausgebildet wurde.

Es is oben gezeigt worden dass dies jedenfalls für den Plan von St.

Gallen nicht zutrifft." Even Edgar Lehmann, in his excellent book Der

frühe deutsche Kirchenbau, shares this erroneous view (Lehmann, 1938,

137).

MEDITERRANEAN OR NORTHERN ROOTS:

A DIVISION OF MINDS

Because of its geographical distribution primarily in the

territory of the Franks, Saxons, and Normans, Georg

Dehio considered the square schematism to be essentially

a "Germanic" contribution.[288]

Samuel Guyer,[289]

in a complete

reversal of this contention declared this "geometrical

clarity" to be a mark "of the Mediterranean way of thinking,"

and "one that had its roots in classical antiquity."[290]

The square schematism of the Plan of St. Gall, he maintained,

was not one of the new and creative contributions

to medieval architecture that it had been assumed to be,

but "transmits to the West in a rather muddled manner the

thought of the qualitatively superior art" of the Early

Christian period.[291]

These statements are of questionable historical validity—

and the argument does not gain in power when one finds it

supported by such sweeping generalities as "A civilization

in process of just awakening from the darkness of an

a-historical past" and "as yet suspended in a state of

unstable hovering between unconsciousness and awakeness"

could not possibly have produced aesthetic concepts

"of such distinct and clear rationality. . . . The period of

Charlemagne had never the significance ascribed to it so

fervently in recent times. . . . In the time of Emperor

Charlemagne the thoughts of Late Antiquity and Early

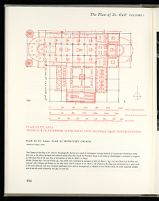

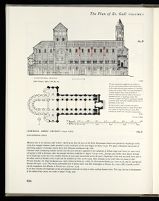

173. PLAN OF ST. GALL. PLAN OF MONASTERY CHURCH

SHOWN AT SCALE 1:600

The Church of the Plan of St. Gall is chronologically the last of a triad of Carolingian transept basilicas of monumental dimensions owing

their size to the tide of spiritual and cultural exhilaration that seized the Frankish clergy in the wake of Charlemagne's coronation as emperor,

on Christmas Eve of the year 800, in the basilica of Old St. Peter's in Rome.

Unlike Cologne (fig. 172) and Fulda (fig. 169) which were occidented in imitation of Old St. Peter's, (fig. 170) the Church of the Plan was

oriented. Like Cologne and Fulda, on the other hand, and in contrast to St. Peter's, the Church of the Plan was constructed on a square grid,

in the most elaborate and most consistent application of it, since it encompassed, in addition to the Church itself, the entire claustral complex

and in fact the entire monastery site (figs. 62 and 63).

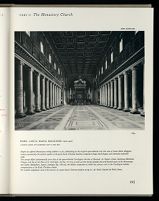

174. ROME. SANTA MARIA MAGGIORE (432-440)

LOOKING NORTH AND SOMEWHAT EAST TO THE APSE

Despite its coffered Renaissance ceiling (added in 1500, substituting for the original open-timbered roof) this view of Santa Maria Maggiore

conveys persuasively the stylistic quality of the great Early Christian basilicas composed of huge, block-shaped, and internally undivided

voids.

The concept differs fundamentally from that of the square-divided Carolingian churches of Neustadt, St. Riquier, Fulda, Reichenau-Mittelzell,

Cologne, and that of the Plan of St. Gall (figs. 167-69; 171-73), as well as from the bay-divided and arch-framed spaces of the Romanesque

and Gothic (Hildesheim, Speyer, Jumièges; figs. 188-90), the cellular composition of which has primary roots in the Carolingian modular

reorganization of the Early Christian scheme.

For another magnificent view of the interior of a great Early Christian basilica see fig. 81, St. Paul's Outside the Walls, Rome.

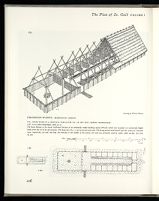

175. FEDDERSEN-WIERDE, BREMERHAVEN, GERMANY

175: AISLED HOUSE OF A CHIEFTAIN, WARF-LAYER 11B, 1ST-2ND CENT. (authors' reconstruction)

176: PLAN (after Haarnagel, 1956, pl. 3)

The house belongs to the second settlement horizon of an artificially raised dwelling mound (Warf) which was occupied, on successively higher

levels, from the 1st to the 4th centuries. The house was 28.5 × 7.5m on an east-west axis. The living portion with hearth and the section for livestock

were, respectively, 9m and 16m long. An entrance in the middle of the eastern end wall was primarily used by cattle. (Also see figs. 315-316, II, 58.)

to be incapable of taking any deep root or of being developed

any further."[292]

I propose that we confine ourselves to specific issues

rather than argue the case in such global terms.

On the question of "square schematism," see Adamy, 1887, 180ff;

Dehio and von Bezold, I, 1892, 161ff.; Effman, I, 1899, 161ff; idem.,

1912, 133ff; Gall, 1930, 16ff.

Guyer, 1950, 116-17. Guyer is over-reacting to a cultural prejudice

that has been ruthlessly expressed by some of the proponents of the

opposite view.

INCREASING PROPENSITY FOR MODULAR

SPACE DIVISION IN PRE-CAROLINGIAN AND

CAROLINGIAN ARCHITECTURE NORTH OF

THE ALPS

The emergence of the square schematism in medieval

architecture depended on two crucial innovations in the

interrelation of the component spaces of the basilican

church:

1. The nave and the transept of the church had to be

given the same width, and

2. The width of the aisles had to be fixed to one-half

the width of the nave.

Without the first, the crossing could not form a square;

without the second, the modular division of the nave could

not be carried into the aisles. Both of these features

occurred separately in Early Christian times, but they were

not integrated then into a programmatic architectural

system.

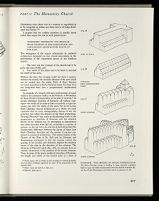

An example of a church with nave and transept of equal 177.A 177.B 177.C 177.D The Early Christian concept of building in large, internally undivided

width is the Justinian basilica of the Nativity at Bethlehem

(if Hans Christ's interpretation of its plan is correct).[293]

In

several Christian churches of Ravenna—all without transepts—the

width of the aisles is fixed at one half, or approximately

one half, the width of the nave. Yet as we survey

Early Christian church architecture as a whole, we must

conclude that its truly distinguishing feature is not the

presence, but rather the absence of any fixed proportions.

Nevenka Petrović[294]

has made an illuminating study of the

proportions in churches of Ravenna and the adjacent

littoral of the Adriatic sea. In attempting to demonstrate

that these churches were laid out according to a system of

squares, as she set out to do, she has de facto illustrated the

fundamental difference between the layout of these later

Early Christian churches and the system of squares employed

in medieval architecture. The salient feature of the

Church of the Plan of St. Gall and its Ottonian and

Romanesque successors is that the squares control the

spacing of the arcades and therefore express the modular

layout of the plan in the elevation of the columns. The

divisions of Petrović's grids (fig. 166), by contrast, have no

relation whatsoever to the position of the arcade columns.

True, in some of the proto-medieval churches of Ravenna,

the length and width of the church exist in a state of

DIAGRAM: TWO MODES OF SPACE COMPOSITION

blocks of space (A) differs fundamentally from bay-divided vernacular (B),

and bay-divided Romanesque and Gothic church construction (C, D).

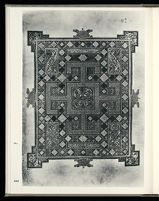

178.

Great Cruciform page

size of original about 33·8 × 24·1cm.

LINDISFARNE GOSPELS

179.A

179.B

LONDON, British Museum, Cotton Nero D. IV, fol. 2v

[by courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum]

Stages of layout

control the spacing of the columns, it is aesthetically of no

consequence.

I tend to agree with George Dehio that the square schematism

is essentially a "Germanic" contribution to Western

architecture for two reasons: first, because it is found

primarily in regions of relatively strong Germanic concentration,[295]

and second, because it is in these areas also that

we may detect its developmental antecedents. An early

medieval church exhibiting an incipient tendency toward

the use of the square as a module was Fulrad's church of

St. Denis, begun after 754 and consecrated in 775 (fig.

167).[296]

Its basic layout, if Formigé's interpretation is correct,

was developed within a grid of 6-foot squares which,

in contrast to San Giovanni Evangelista at Ravenna (fig.

166), determined not only the overall dimensions of nave

and transept, but also the interstices of its arcades. The

transept was seven 6-foot units wide, and thirteen long; the

nave was five units wide and fifteen long. The distance from

center to center of arcade columns was two units, and in the

middle part of the transept two cruciform piers establish a

square of five by five units. As yet we cannot speak of

square schematism, because the dimensions of the crossing

square are not mirrored anywhere else in the building, and

in particular not in the intercolumniation of the arcades. A

church that comes closer to this ideal is the Saviour's

Church of Neustadt-on-the-Main, after 768/69 (fig. 167).

The plan of this church together with other cruciform

churches of similar design built in early medieval times,

such as Pfalzel near Trier, and Metlach (both before 713),

may have formed a connecting link between square-divided

Carolingian basilicas of the ninth century and certain

cruciform churches of the fourth and fifth centuries, typical

examples of which are shown in fig. 144-146 and 148-149.

A grandiose variant of this church type, built as early as

380 by Emperor Gratian in his residential city of Trier,

rose in territory that later was part of the very core of the

Frankish kingdom—for every Carolingian to see! (Its

masonry survives to this day, incorporated in the fabric of

the Romanesque church that superseded it.) This is the

only pre-medieval church type where nave and transept

are of equal width, their intersecting bodies forming a

square—and one might indeed regard the fully developed

square schematism of the Carolingian period as a transference

to churches of basilican plan of a principle already

experimented with in pre-medieval times in the highly

specialized context of these Early Christian cross-in-square

180. LINDISFARNE GOSPELS

LONDON, British Museum, Cotton Nero D.IV, fol 2v

Square panel above arm of cross on cruciform page shown in fig. 178

A. Photo of panel

B. Photo of square grid visible on corresponding portion of

fol. 4r.C. Square grid with outlines of cross and lozenge pattern

(first stage of construction)D. Final stage of pattern (authors' interpretation)

significant moment of the adoption of the

square schematism in a building of unequivocally basilican

design was the abbey church of Centula, 790-799, if

Irmingard Achter's reconstruction of this building is

correct (fig. 170).[298] Because of the scarcity of archaeological

data available on this important building, such an assumption

can neither be fully accepted nor convincingly

rejected. For the same reason it is impossible to ascertain

whether the interstices of the nave arcades were aligned

with these modules.

Modular adjustment between width and length of the

component spaces is clearly visible, however, in the abbey

church of Fulda (802-817).[299]

Its nave, measured from the

base of its western to that of its eastern apse, was exactly

four times its width (fig. 169). The dimensions of the

transept were identical with those of the nave. In the vast

body of literature devoted to Fulda—whose authors never

weary of citing the dependence of its design on that of Old

St. Peter's—this crucial aesthetic novelty has never been

pointed out, much less set into proper historical perspective.

We know nothing about the intercolumniation of

Fulda.

On the other hand, it is not possible to interpret Old

St. Peter's as having been developed within a grid of

identical squares—neither each volume by itself, nor any

volume in relation to a neighboring unit or to the whole of

the building mass. The architect who planned St. Peter's

employed instead a constructional system as classical in

concept as the modularity of the Carolingian churches

shown in figs. 144ff is medieval (see Born's analysis, fig.

170). He calculated the length of the longitudinal body of

the church by making use of the diagonal of a square with a

side equal to the width of the church, and developed the

overall length of the church in the same manner, with the

aid of the diagonal of the rectangle obtained by the preceding

method. This configuration, known as a √2

rectangle, is irrational, since the diagonal of a square is not

in any integral relationship to its sides (1: √2 = 1:1.414)

and therefore cannot be defined as an aggregation of an

integral modular value.

Hildebold's church of Cologne (ca. 800-819) was

composed wholly of equal squares: three in the transept,

four in the nave, one in the fore choir (fig. 172). If the

elevation of its nave walls was identical with that of the

church dedicated in 870, the piers of the arcades that

carried the clerestory walls would not have been in alignment

with this system.

The abbey church of Reichenau-Mittelzell, built by

Haito (806-816) is also developed within a modular grid of

squares, but the grid is irregular, and its existence, for that

reason, has been questioned. In evaluating this problem it

is important to distinguish the existence or nonexistence of

the concept of squares at Reichenau from the regularity or

perfection of its execution. The irregularity, in the angular

deviation of the walls from the grid (especially noticeable in

the eastern part of the church) is caused by special topographical

conditions. But no doubt can be entertained that

the concept exists. The shape of the fore choir and of the two

transept arms are almost a mirror image of the shape of the

crossing square, but the squares of the nave are slightly

oblong. Yet the principle of divisions is clearly there, and

the boundary between the two oblongs of the nave is

marked by piers, whose design differs from the columns

standing midway between them. In this feature St. Mary's

Church at Reichenau goes a step beyond even the Church

of the Plan of St. Gall, which has no such alternation in its

main supports.

In Hildebold's church of Cologne (fig. 172) the system

of squares finds clear expression in the west transept and

in the eastern fore choir, both of which are formed of squares

of identical size: three in the transept, one in the fore choir.

The nave is composed of four squares of like dimensions.

We know nothing about its elevation. If it was identical

with that of the church that was dedicated in 870, the piers

of the arcades which carry the clerestory walls would not

have been in alignment with the system of squares.

In the Church of the Plan of St. Gall the square schematism

attains its purest Carolingian form of expression (fig.

173). The basic unit is the 40-foot module of the crossing

square. The transept is formed of three such squares, the

fore choir of one, the nave of four and one-half; and the

dimensions of the crossing square are echoed even in the

Library and Vestiary. In St. Gall, moreover, the interstices

of the columns are in rhythmical alignment with the

squares. It is incomprehensible to me how this fact should

ever have been questioned. What the designer of this

church had in mind were arcades cutting deep into the

masonry of the nave walls (fig. 110) with their supports so

spaced as to give bodily expression to the sequence of

squares on which the Plan was based. This schematism is

a conscious and willed aesthetic principle. It is a fundamentally

different concept from that which produced the

low, narrowly spaced columnar orders of the Early Christian

basilicas of Rome (figs. 141 and 174). Contrary to what

Guyer, Reinhardt, and Reinle believe, it is an ingenious

anticipation of the square schematism of the Romanesque.

What are the historical preconditions of this propensity

for modular organization of space? Some clearly are functional.

181.

Cruciform page preceding the Gospels of St. Luke

size of original about 33·8 × 23·1cm.

182. LINDISFARNE GOSPELS

LONDON, British Museum, Cotton Nero D. IV, fol. 138r

[by courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum]

Diagram illustrating use of square grid in constructing the layout for

the opposite illustration

For still others we shall have to reach, beyond the

boundaries of architectural history, into the field of book

illumination, where strong expression of modular modes

of thinking can be observed over a century before they

assert themselves in church building. Yet others, and perhaps

the most important of all, may have to be sought in

deeper and more general cultural levels.

Formigé, 1960, 51 and 57. Formigé's interpretation of the layout of

the transept of Fulrad's church differs from that of Crosby, but the

differences and their rationale are nowhere discussed as far as I can

determine. (Cf. Crosby, 1966, 7 Figs., 1 and 6, note 4.) There appears to

be no disagreement with regard to the layout of the nave of the church.

On the emergence of modular thinking in Carolingian architecture

see Horn and Born, 1975, 351-390. In this same publication Charles W.

Jones and Richard E. Crocker deal with emergence of similar concepts in

literary and musical composition of the Carolingian period.

For Neustadt-on-the-Main and Metlach see Boeckelmann, 1952, 109ff

and Boeckelmann, 1956. For Pfalzel see Vorromanische Kirchenbauten,

ed. Oswald et al., 1966-1967, 259. For Trier see Krautheimer, 1965, 61,

fig. 23.

For a fuller discussion of Fulda in relation to St. Peter's and the

historical position of Haito's church at Reichenau-Mittelzell in the

development of modular concepts of organizing space see Horn and

Born, 1975.

NEW LITURGICAL NEEDS

CONTRIBUTING TO MODULAR SPACE DIVISION

I have already drawn attention to a number of contributing

factors that tended to facilitate this development in a functional

sense: the need for an extension of the altar space,

leading to the interposition of a new spatial unit between

transept and apse; the framing of the crossing by means of

arches, creating a square division in the transept, that would

lend itself to being extended to the nave; and most of all,

perhaps, the multiplication of altars, demanding a subdivision

of the spaces of nave and aisles into a sequence of

devotional stations (figs. 164 and 165). We add to this a

feature (which Irmingard Achter stressed in her discussion

of the Carolingian Abbey Church of Centula): circular

towers such as the towers which surmounted the crossing

and the westwork of this church require as base a square-shaped

underpinning. All of these innovations contributed

to the development of a modular scheme, but none of them

alone (and perhaps, not even all together), might have

led to the creation of the modular space division of the

medieval church as a binding architectural principle. There

are other forces to be taken into account.

MODULAR SPACE DIVISION: AN INTRINSIC

FEATURE OF PREHISTORIC, PROTOHISTORIC, AND

MEDIEVAL WOOD CONSTRUCTION

In an article dealing with the origins of the medieval bay

system,[300]

I have pointed out that modular design has been

from the remotest periods an intrinsic feature of northern

wood construction. The stability of the timbered Germanic

house required that its roof-supporting posts be joined

together at the top: lengthwise by means of plates, and

crosswise by means of tie beams. This divides the space of

the house into a modular sequence of timber-framed bays

(figs. 175 and 176). Recent excavations have made it clear

that this construction type came into existence around 1200

B.C., and for the next two thousand years it served as an

all-purpose house in the Germanic territories of Holland,

Germany, England, and Scandinavia as well as in all those

areas of Central and Western Europe that were primarily

settled by Germanic peoples.[301]

In timber this concept is

old; in stone it is new. In timber it develops as a logical

construction method from the natural properties of the

Canon Tables (183.A)

The Ada Gospels is the first great highlight of the classicizing phase of

illumination of the so-called Court School. It consists of an earlier part

(fols. 6-38) containing the canon tables (fols. 6v-11v) which combine the

decorative tradition of the Hiberno-Saxon school (figs. 178-182) with a tendency

to treat the arcades of the tables in a more architectural manner.

Size of leaves of the manuscript in the present cropped state is 36 × 24.5cm.

Figures 183.A and 183.B are reduced about 12.5 percent.

Originally the leaves were larger.

The later part of the Ada Gospels consists of the remainder of the text, and

portraits of the four evangelists (fols. 15v, 59v, 85v, 127v), one of which is

illustrated in fig. 184 (see overleaf).

183.C ADA GOSPELS (EARLY 9TH CENT.)

DIAGRAM SHOWING USE OF SQUARE GRID IN THE

CONSTRUCTION OF THE CANON TABLES SHOWN IN

183.A AND 183.B (see overleaf)

TRIER, Municipal Library, MS. XXII, fol. 6v

upon the material as a willed aesthetic principle—and

therefore ushers in a conflict between style and building

material which, in its ultimate phase, the Gothic, led to a

complete denial of the natural properties of stone. I have

suggested that the modular arrangement of space, which

begins in Carolingian Church architecture, gathers increasing

strength in the Ottonian period and reaches its peak of

expression in the Romanesque and Gothic (fig. 177), has

one of its roots in the fact that these churches were constructed

by men in whose collective memory "to build"

had been synonymous with building in modular sequences

of space.

The validity and importance of this explanation cannot

be appreciated until it is understood that the determining

factor in analyzing the origins of square schematism is not

that it is based on the shape of the square, but that it

establishes a system of binding modular relationships. In

distinguishing between the système des carrés of the Romanesque

and the système des barlongs of the Gothic, we have

lost sight of the fact that both of these systems are members

of the same family. Whether the module is square or

rectangular is determined by secondary conditions, sometimes

functional, sometimes constructional, sometimes

stylistic, and on occasion, even by purely arbitrary reasons.

The house of the Germanic chieftain of the first and second

centuries A.D., which is shown in figures 175-176, employs

both the square and the rectangular module, the former in

the living area, identifiable by the hearth; the latter, in the

section of the house where the cattle are stabled, identifiable

by the manure mats.[302]

Here the shape of the module is

conditioned by strictly functional considerations: the roof-supporting

trusses are spaced at intervals of 6 to 7 feet, just

as much space as is needed to stable two head of cattle. In

the living section of the house, on the other hand, the

trusses are set further apart to give greater freedom of

movement. The distinction is very old and can be observed

in Bronze Age houses of the same construction type, dating

from around 1200 B.C., recently excavated by Waterbolk in

Elp, Holland.[303]

In the Carolingian monastery churches discussed in the

preceding pages, the square is the more reasonable form

to be adopted—at least in the liturgically most important

areas—the choir and the transept— which lend themselves

to square division with notable ease. In the nave, this was

more difficult to obtain, since here the square division

conflicted with the narrow intercolumniation inherited

from the Early Christian prototype churches. It required

a strong personality to move the columns apart to the novel

and daring distance of 20 feet, as was done in the Church

of the Plan, and thus to express the module in the bodily

sequence on the columns. The designer of the Church of

Cologne may have struggled with similar ideas (fig. 172), but

abandoned the scheme in actual construction (figs. 15-16).

183.B

183.D ADA GOSPELS

DIAGRAM SHOWING USE OF SQUARE GRID

TRIER, Municipal Library, MS. XXII, fol. 8v

For a brief review of this material, prehistoric and medieval, see

Horn, 1958, 2-16, and II, 23-77.

MODULAR AREA DIVISION: AN INTRINSIC

FEATURE IN THE LAYOUT AND DESIGN

OF ILLUMINATED PAGES IN HIBERNO-SAXON

AND CAROLINGIAN MANUSCRIPTS

The modular bay division that governed the construction

of the Germanic house from the first millennium B.C.

onward was not the only source for the appearance of

modular relationships in Carolingian church architecture. It

may, in fact, take second place when weighed against

another influence, which reflects an attitude of mind more

than a constructional necessity. An organization based on

modules is one of the distinguishing features of the layout

of the illuminated pages of Hiberno-Saxon and Carolingian

manuscripts.

Figures 179.A and 179.B show how the artist of the Lindisfarne

Gospels set out to decorate the large cruciform page

that forms the frontispiece (fol. 2v) to this remarkable book

(fig. 178).[304]

The principal motif is a square-headed cross

framed by a narrow band and decorated internally with a

key pattern. In the field between the arms of the cross and

the outer frame of the page, there are four panels with step

patterns, two square ones on the top, two of oblong shape

at the bottom. The background is filled with an intricate

design of interlace. The page is framed by a strip of interlaced

birds, held in by narrow bands which terminate at

each of the four corners in an ornamental knot.

An analysis of the construction method used in setting

out the design of this page shows that all the basic divisions

are multiples of the width of the framing bands. The basic

values are 5 · 6 · 7 · 12 (fig. 179.A). The squares of the cross

measure 12 · 12; the panels in the fields above and beneath

the arms of the cross are 10 · 10 and 10 · 25. I feel certain

that a system of linear coordinates, such as is shown in

figures 179.A and B, was laid out on the page, by means of

either lines or prickings before the artist entered the

decorative details. In certain places where the design was

very intricate, such as the panels above and under the arms

of the cross with their complicated step patterns (fig. 180.A),

the illuminator actually drew out the lines with the point

of a fine stylus. This is visible on the opposite side of the

sheet (fol. 2r) as a grid of delicately protruding ridges (fig.

180.B).[305]

I have shown in figures 180.C and D how this system was

worked out. First, the illuminator divided the square

internally into sixteen subordinate squares by the method

of continuous halving. Then he divided each subordinate

square into nine base squares through internal tri-section.

This furnished him with all the desired linear co-ordinates

for the lozenge, cross, and step patterns with which these

squares are decorated (fig. 180.A). The same or similar

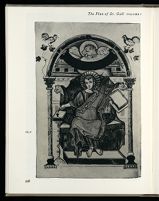

184.A St. Luke

The Ada Gospel portraits of the four evangelists framed by arcades

(fols. 15v, 59v, 85v, 127v) depend stylistically on a Late Antique

manuscript tradition combining the sculptural corporeality of Roman

figure style with touches of Byzantine mannerism.

Revived in the art of the Frankish illuminators of the Court School,

this tradition merged with the northern concept of organization of

space. This first encounter of the two traditions is not reflected in the

portrayal of the Ada evangelists, but visibly controls the layout of

the surface in which their images are placed. Later, in a synthesis of

southern corporeality and northern abstraction that parallels the

same development in architecture, these concepts will produce a

figure style that, despite strong dependance on classical prototypes, is

distinctly medieval (see fig. 185).

184.B ADA GOSPELS (EARLY 9TH CENT.)

DIAGRAM SHOWING USE OF SQUARE GRID IN CONSTRUCTION

OF ARCH FRAMING

TRIER. Municipal Library. MS XXII, fol. 59v

manuscript, and also in the layout of the canon tables (fol.

10r-fol. 17r).

Figures 182.A, B, and C give an analysis of the design

of the great cruciform page on fol. 138v that precedes the

Gospel of St. Luke (fig. 181).[306]

This page has as its main

motif a cross with T-shaped arms, filled in with a background

of interlaced patterns; the spaces around the cross

are filled with an animal interlace. The entire decoration of

this page is laid out on a system of squares, each side of

which is four times the width of the framing band. The

page measures thirteen units across and seventeen units up

and down. The transverse axis of the cross is laid out in

the sequence:

4 · 12 · 4 · 12 · 4 · 12 · 4

the vertical axis in the sequence:

4 · 4 · 4 · 12 · 4 · 12 · 4 · 12 · 4 · 4 · 4

The protruding knots at the corners and in the prolongation

of the two intersecting axes of the page are inscribed

into a marginal area seven units wide.

These principles of modular book design so typical of

Hiberno-Saxon art were inherited by the continental

Carolingian illuminators. Figures 183.C and D are a design

analysis of two of the canon tables of the Ada Gospels, fol.

6v and fol. 8v (figs. 183.A and B).[307]

The layout of these

tables varies. Some have four arcades, others have three.

As in the Lindisfarne Gospels all the internal subdivisions of

these pages are calculated as multiples of the width of the

framing bands. In both tables the design is suspended in a

square grid composed of 4 × 4 base units.

On fol. 6v (figs. 183.A and C) the bases of the columns

and their interstices are calculated in the sequence:

14 · 2 · 14 · 2 · 14 · 2 · 14 · 2 · 14

the column shafts and their interstices in the sequence:

4 · 12 · 4 · 12 · 4 · 12 · 4 · 12 · 4

The columns are inscribed into a grid of 16 × 19 squares,

the arches into a 9 × 19-square grid.

The canon arch on fol. 8v (figs. 183.B and D) has only

three columns. It is based on the same grid pattern. The

bases of the columns are calculated in the sequence:

16 · 4 · 16 · 4 · 16 · 4 · 16

the column shafts and their interstices in the sequence:

4 · 16 · 4 · 16 · 4 · 16 · 4

Figures 184.A and B show that the same method of construction

is used in the layout of the arch which frames the

figure of St. Mark on fol. 59v of the Ada Gospels. The basic

185. CODEX AUREUS OF ECHTERNACH

MADRID, Escorial, Cod. Vitr. 17, fol. 2v

[by courtesy of the Patrimonio Nacional]

Emperor Konrad and Empress Gisela prostrate themselves before

Christ in Majesty. School of Echternach, 1043-1046. The Gospel

book was presented to Speyer between 1043 and 1046 by Henry III

(1038-1056) who (folio 3v) is portrayed with Agnes, his consort, in

the act of transmitting the manuscript to Mary, patron saint of the

cathedral. Both illuminations are high points in the synthesis of a

figurative style rooted in Antiquity, with a medieval propensity for

planimetric order and linear simplicity pervading both figurative and

geometric components of each picture (rectangle, lozenge, circles,

semicircles). Byzantinizing mannerisms (cf. fig. 184) are dropped;

the figures have acquired the magnificent blocklike stance that

characterizes much of the contemporary sculpture.

The columnar section is a square, 20 × 20 units; the arch

section, an oblong of 9 × 20 units.

The square grid affects the layout of the page, but not the

design of the figure of the Evangelist. This latter is clearly

patterned after a Byzantine model. The conflict between

the corporeal emphasis of the classical design, and the

tendency of the northern medieval illuminator to subject

the borrowed image to linearism and geometricity provoked

a developmental dialectic in which the ability to absorb

classical influences with increasing strength, in successive

stages, is preconditioned by a partial rejection and successful

transformation of those absorbed in a preceding phase.

In the period of the Romanesque, as a consequence of this

dialectic, solutions are obtained in which southern corporeality

and northern abstraction enter into a state of

balance (fig. 185). In like manner in the field of architecture,

southern masonry tradition fuses with northern frame

construction in a marriage in which the two component

traditions are matched with consummate perfection (fig.

186).

The square schematism is the primary organizing agent

in this development. It helps to disassemble the large

corporeal spaces of the Early Christian basilica, and to

arrange its parts in modular sequences that could be

vaulted. It determines the take-off points for the rising

shafts and arches that were needed to carry the vaults.

Millar, 1923, pl. I; Codex Lindisfarniensis, 1956, fol. 2v. As my

analysis is based on photographic reproductions, the validity of these

observations must be checked against the original.

This fact has been observed and pointed out by Millar, 1923, 20-21.

The grid is clearly visible in the facsimile edition (Codex Lindisfarniensis,

1956, fol. 2r) from which figure 180.B is taken.

My analysis is based on the photographs published by Janitschek

in 1889. I have had an opportunity to check my observations against the

original in Trier and found that my drawings were not reliable in every

detail, but not to the extent of invalidating the basic tenets of the

theory proposed here.

MODULAR AREA DIVISION:

AN INTELLECTUAL PRINCIPLE AFFECTING THE

CONCEPTUAL ORGANIZATION IN THE

RELATIONSHIP OF CHURCH AND STATE

It has become a commonplace of historical reference to

speak of the "anthropomorphic" character of Greco-Roman

and Late Antique art and of the "corporeal"

quality of their figurative and spatial composition; and it

has been stressed time and again that this quality grows

out of a way of thinking that interprets man and his metaphysical

environment "in the image of man," a concept so

embedded that even Christianity could not rout it. We

have not yet found any way of describing or explaining

adequately the way of thinking that impelled the medieval

illuminators to submit the classical prototypes to relentless

abstraction and caused the medieval architects to break up

and reassemble their spaces in controlled volumetrical

sequences.[308]

Until we have, we shall not be able to understand

fully the meaning of such a phenomenon as the

square schematism of medieval art or, for that matter, any

other schematisms conceptually related to it. Square

schematism is an intellectual principle by which formerly

existent, yet isolated or only loosely connected parts are

brought into an ordered modular relationship. It is a

principle of intellectual alignment that strikes far beyond

the reality of architecture or book illumination into the

realm of literary and musical composition—as Charles W.

Jones and Richard D. Crocker have shown in recent

studies[309]

—reflect a cultural attitude that may have had a

186. SPEYER CATHEDRAL (1082-1106)

[after Dehio, GESCHICHTE DER DEUTSCHEN KUNST,

4th ed., I, 1930, plate vol., figure 63]

About 1030, Emperor Konrad II (1029-1039) began to replace the

Merovingian cathedral with a new building (Speyer I) whose crypt

(dedicated in 1041) became a sepulchral sanctuary for the imperial

house. The nave walls of this structure were articulated by a

continuous sequence of engaged shafts rising from the floor to the

head of the walls. The roof was timbered. The aisles by contrast were

covered with shaft-supported and arch-framed groin vaults.

During the reign of Emperor Henry IV (1056-1106, or more

precisely from about 1082-1106), the design of the aisles was

transferred to the nave by the superimposition upon each alternate

tier of a second and heavier shaft, and their connection lengthwise

and crosswise by means of arches capable of carrying vaults. The

view shown above represents the cathedral in the form it had attained

at this point (Speyer II).

of Church and State, where similar tendencies can be observed

at about the same time. An illuminative reflection of

this mode of thinking is to be found in Walahfrid Strabo's

Libellus de Exordiis, written between 840 and 842. Here

secular rulership and ecclesiastical government are brought

into a system of modular relationships in which each of the

two respective hierarchies is formed by a series of parallel

offices:

Just as the Roman emperors are said to have been the monarchs of

the whole world, so the pontiff of the see of Rome, filling the place

of the Apostle Peter, is at the very head of all the church. We may

compare archbishops to kings, metropolitans to dukes. What the

counts and prefects perform in the secular world, the bishops do in

the church. Just as there are praetors or comites palatii who hear the

cases of secular men, so there are the men whom the Franks call the

highest chaplains who preside over the cases of clerics. The lesser

chaplains are just like those whom we call in Gallic fashion the

lord's vassals (vassos dominicos).[310]

Like the "disengaged crossing" or the "extended altar

square" many of the component parts of this system are

old. But the manner in which they were drawn together

into a system of homologous parts presaged a development

which, two to three centuries later, led to the accomplished

and intensely sophisticated metaphysical visions of scholastics.

They envisioned the universe as a triad of structurally

related hierarchies (fig. 187)—each being an identical image

of the other as well as of the system as a whole—that

possessed identical subdivisions into triads of ranks, and

in each of these triads each subordinate rank corresponded

in substance to its equivalent part in every other triad.[311]

I have dealt with a typical expression of this conflict between classical

corporeality and medieval abstraction in my article on the Baptistery

of Florence; see Horn, 1938, 126ff.

Translation quoted after Odegaard, 1945, 20-21. For the original

text see Walafridi Strabonis libellus de exordiis et incrementis quarundam

in observationibus ecclesiasticis rebus, ed. Krause, in Mon. Germ. Hist.,

Legum II, Capit. II:2, 515-16; "Sicut augusti Romanorum totius orbis

monarchiam tenuisse feruntur, ita summus pontifex in sede Romana vicem

beati Petri gerens totius ecclesiae apice sublimatur . . . Deinde archiepiscopos

. . . regibus conferamus; metropolitanos autem ducibus comparemus . . . Quod

comites vel praefecti in seculo, hoc episcopi ceteri in ecclesia explent . . .

Quemadmodum sunt in palatiis praetores vel comites palatii, qui saecularium

causas ventilant, ita sunt et illi, quos summos capellanos Franci appellant,

clericorum causis praelati. Capellani minores ita sunt, sicut hi, quos vassos

dominicos Gallica consuetudine nominamus. Dicti sunt autem primitus

cappellani a cappa beati Martini, quam reges Francorum ob adiutorium

victoriae in proeliis solebant secum habere, quam ferentes et custodientes cum

ceteris sanctorum reliquiis clerici cappellani coeperunt vocari."

The diagram shown in fig. 187 is based on Berthold Vallentin's

analysis of William's Liber de Universo, in Gustav Schmoller, Grundrisse

und Bausteine zur Staats-und zur Geschichtslehre (Berlin, 1908, 41-120).

It was first published in Horn, 1958, 19, fig. 42.

SETBACK AND RE-EMERGENCE

On the preceding pages I have shown that the square

schematism appeared in western architecture neither as

187. WILLIAM OF AUVERGNE. LIBER DE UNIVERSO (1230-1236)

HIERARCHIES OF HEAVEN, STATE AND CHURCH

[Author's diagrammatic interpretation]

Components of this concept are Early Christian; their integration into an all-embracing metaphysical scheme is medieval. Similarities in the institutional

organization of Church and State were apparent in the 4th century after the Church began to model its administrative structure after that

of the State. Carolingian awareness of this fact is attested by the passage of Walahfrid Strabo quoted above, p. 231.

Dionysius the Pseudo-Areopagite (5th-6th cent.) speculated that the celestial hierarchies of angels and the orders of the Church were parallel. This

concept became a central theme of Carolingian theology after a manuscript of Dionysius (presented to Pepin I by Pope Paul in 758) had been

translated into Latin by Hilduin of St. Denis. (For more detail see Glossary, s.v. Hierarchy.)

HILDESHEIM. ST. MICHAEL'S CHURCH (1010-1033)

188.B

188.A

Alternating piers and columns at modular intervals is a leitmotif of Ottonian architecture, but has sporadic Carolingian antecedents in Reichenau-Mittelzell

(figs. 117, 134, 171), Werden (Vorromanische Kirchenbauten, 1966-71, 372ff), and the basilica of Solnhofen (see V. Milojcic,

Ausgrabungen in Deutschland, II, Mainz, 1975, 278-312).

formerly thought. This raises the question: why, once

conceived, did it so suddenly disappear, not to re-emerge

until almost two centuries later?

The answer to this, I think, is relatively simple. The

square schematism, in the highly sophisticated and accomplished

form, which it attained in the layout of the Church

of the Plan of St. Gall, was born within the conceptual

framework of a building that had an overall length of no

less than 300 feet and for that reason could readily be

divided internally into a sequence of 40-foot squares. When

in the revisionary textual titles of the Plan it was suggested

that the church be reduced to a length of 200 feet and that

the columnar interstices be shortened from 20 to 12 feet,[312]

the modular order of the original layout was demolished.

There is no evidence to suggest that this reduction in size

was conditioned by structural or aesthetic considerations.

The change occurred as has been shown,[313]

at more or less

the same time—and probably for the same reasons for

which—the abbot of Fulda was deposed for overtaxing the

spiritual and economic resources of his monastery with the

construction of a church considered by his monks as being

outrageously large. In this historical climate the dimensions

of the Church of the Plan of St. Gall, as laid down in the

drawing, could no longer be considered prototypal. The

JUMIÈGES, ABBEY CHURCH (1040-1067)

189.B

The red overprinting supplied by the authors on

Lanfry's fine drawing indicates where certain scars

in the original masonry give evidence of a structural

feature now vanished. This is by some interpreted as

a simple engaged column rising from floor to

clerestory wall-head level, by others as the seat of

abutment masonry of diaphragm arches. The

controversy requires thorough re-examination through

a masonry study made from scaffolds giving access to

full height of nave wall.

As long as such a study is lacking, and until a

structural engineering analysis is made, Ernest Born

and I prefer to keep the controversy alive, Born

favoring the former and I the latter interpretation.

W.H.

189.A

SEINE-INFÉRIEURE, FRANCE

Masonry scars in its clerestory walls (189.C, 189.D) prove that the nave of this Early Romanesque church was spanned by diaphragm arches

rising from engaged columnar shafts attached to every second pier of the nave (begun not before 1052). The square schematism and system of

alternating supports of Jumièges clearly derive from Ottonian architecture (fig. 188).

Columnar shafts introducing modular division into the nave walls first appeared in the cathedrals of Orléans (990) and Tours (ca. 990-1002)

and gained a hold in Germany, after the principle had been established in Speyer I (1030-1061). Jumièges goes further than Speyer through

use of diaphragm arches that carry modular division of nave walls transversely across the space. Diaphragm arches had previously been used in

the abbey church of Nivelles (1000-1046) and the cathedral of Trier (1016-1047). After Jumièges (1052-1067) they are found in other

Norman churches: St. Vigor-de-Bayeux (ca. 1060), Cérizy-la-Foret (ca. 1080), St. Gervaise-de-Falaise (ca. 1100-1123), and St. Georges-de-Boscherville

(after 1114). They become fashionable even in distant Italy: San Pier Scheraggio in Florence (ca. 1050-1086), Lomello (1060?)

and the magnificent San Miniato in Florence (ca. 1070-ca. 1150).

In all these churches the diaphragm arches were placed at intervals too large to allow vaulting between them. This step, the last in development

of the medieval bay system, was made in Speyer II (fig. 190).

189.C SOUTH WALL OF NAVE

Southwest view (toward the Seine and the quarry site for the stones

of Jumièges, showing clerestory windows.

Originally the nave of the church was covered by an open timber

roof, which in 1688-92 was concealed under a vaulted wooden

ceiling supported by sculptured brackets and foliated capitals inserted

on sill level of the clerestory windows.

On this occasion scars were left in clerestory walls through the

removal of some feature, which some believe to have been a

diaphragm arch (Pfitzer, Michon, Horn) and others a simple

engaged column (Martin Du Gard, Lanfry, Born).

189.D DETAIL

A close view shows one of the masonry scars left on the inner face of the

clerestory walls when the original feature for which it formed a seating was

removed, to make room for a vaulted 17th-century ceiling. It is the narrowness

and shallowness of these scars, as well as the height and thinness of the

clerestory walls, that induced earlier scholars to discard the assumption of

diaphragm arches.

Against this view it can be argued that for roughly two-thirds of their total

height, the nave walls are externally buttressed by the gallery vaults of the

church; and that along the lines where the scars occur, the clerestory is externally

reinforced by engoged buttresses rising from the galleries to clerestory wall-head

level. For a good summary of the controversy, see Michon-Du Gard, 1927.

47-54.

SPEYER CATHEDRAL (1082-1106)

190.B

190.A

[redrawn by Ernest Born after plans by

Dehio, Geschichte der Deutschen Kunst, 3rd ed., plate vol. I, figs. 68-69;

Kubach and Haas, 1972, pl. 9; and Conant, 1959, 75, fig. 22]

The great conceptual leap from Early to High Romanesque architecture was made by introducing continuous sequences of arch-framed vaults

springing from shafts that reached from floor to head of clerestory walls. Modularity, now embodied in an armature of architectural members

pervading and framing space in all directions, thus acquired its fully medieval form. The Ottonian "box-space" was transformed into the

bay-divided medieval space. The Gothic changed the vocabulary, but not the fundamental concept of space.

A basilica of magnificent longitudinal sweep and breathtaking verticality (70m. long, over 30m. high), Speyer was the first full embodiment of

this principle of composing churches in continuous sequences of clearly definable modular units of space.

shattering blow in the neo-asceticism of the monastic reform

movement, and, in consequence, was abandoned.

The political chaos that followed the reign of Louis the

Pious offered no opportunities for a return to the earlier

concepts. Their renascence had to await the political and

economic consolidation that was brought about in Germany

by the house of the Saxon kings, and in France by the rising

power and importance of the dukes of Normandy that

peaked in the conquest of England.

The steps that lead to the re-emergence of square

schematism in Ottonian and Norman architecture are well

known and need not be reiterated. They are marked by

such highlights of medieval architecture as St. Michael's

Church at Hildesheim, 1010-1033 (fig. 188); the Abbey

Church of Jumièges, 1040-1061 (fig. 189); and the second

stage of the imperial cathedral of Speyer, ca. 1080-1106

(figs. 186 and 190).

St. Michael's at Hildesheim had a total length of 230 feet

and was internally composed of a sequence of seven

modules 30 feet square plus an apse with a radius of 20 feet

(fig. 188).[314]

One could not wilfully construct a more convincing

mirror-image of the modular square division of the

Church of the Plan of St. Gall (figs. 61 and 173).

I do not know of the existence of any accurate measurement

studies of the Abbey Church of Jumièges (10401067).

But from the plans of Martin du Gard[315]

and of

Lanfry[316]

one gains the impression that it might have been

based on a modular sequence of 35-foot squares, four of

those composing the nave, one the crossing, one the fore

choir, and one half the apse, for a total of six and one-half

squares.

Whether or not the renascence of these modular concepts

at Hildesheim and Jumièges has any direct connection with

the Plan of St. Gall is impossible to say. The discussion of

this subject has suffered from the fact that until very

recently the square schematism even of the Church of the

Plan of St. Gall had been questioned.[317]

Yet the similarities

can hardly be overlooked. As in the Church of the Plan of

St. Gall (fig. 61), so in Hildesheim and in Jumièges the

general dimensions of the principal spaces were calculated

as multiples of the crossing square. In both of these churches

this modular division was aesthetically underscored by a

rhythmical alternation of light supports with heavy supports,

the latter marking the corners of the module, the

former rising in the interstices between them. The system

has two isolated Carolingian precursors in the abbey

churches of Werden (dedicated 804)[318]

and Reichenau-Mittelzell

(consecrated in 816)[319]

but becomes a governing

principle of style only in the Ottonian period, starting with

the abbey church of Gernrode (961-965)[320]

and leading

from there in successive steps of refinement through the

magnificent series Hildesheim[321]

—Jumièges—Speyer. A

feature of primary developmental implications—completely

overlooked in all authoritative studies on the Abbey Church

of Jumièges—were the great diaphragm arches that spanned

the nave crosswise, rising from shafts attached to every

alternate pier.[322]

Aesthetically this is a first attempt to visually connect the

alternating support articulation of the nave walls with the

aid of a bold transverse member reaching full width across

the space of the nave as well as full height into the roof of

the structure. The diaphragm arch has been variously derived

from Roman,[323]

Syrian,[324]

Mohammedan,[325]

and

Italian[326]

sources; but its prototype is much closer at hand;

in the masonry arches that frame the area of intersection in

churches with nave and transept of equal height, and

establish in the transepts of these churches a modular cross

division of space that precedes that of the nave by centuries

(Church of the Plan of St. Gall, 816-17; Hildebold's

Cathedral of Cologne, after 800 and before 819; and perhaps

even the abbey church of St. Riquier, 790-799).[327]

The ultimate prototype of the diaphragm arch is, of course,

the triumphal arch of the Early Christian basilica[328]

and

the longitudinal body of the church are the aisles, where

precocious modular cross division by means of transverse

arches appear as early as the beginning of the ninth century

(Werden-on-the-Ruhr, dedicated by Bishop Ludger in 804

and Reichenau-Mittelzell, consecrated by Bishop Haito in

816).

The transept of the Cathedral of Speyer looks as though

it might have been conceived as a triad of 50-foot squares.[329]

The spacing of the piers in the original building (Speyer I,

constructed between 1030 and 1061) did not perpetuate

these dimensions; and when the nave, between 1080 and

1106 (Speyer II) was covered by groin vaults, mounted on

arches rising from shafts attached to every alternate pier,

this resulted in a sequence of oblongs rather than squares.

This variance in modular shape and size is an impurity of

minor importance; the epochal historical advance achieved

in Speyer was that the modular division of the ground floor

was here, for the first time, embodied in an all-pervasive

system of shafts and arches that divided the space lengthwise

and crosswise as well as in its entire height into a

modular sequence of clearly definable cells or bays. Once

this point was reached, the walls between the rising shafts

and arches could be perforated—and were in fact transformed

progressively into that intensely skeletal armature

of shafts and arches that led to the formation of the Gothic.

The self-contained and divisive vaults that covered the

bays of Romanesque and Gothic churches—firmly set off

against each other by their strong relief of framing arches

and ribs—were bound to strengthen the modular organization

of the spaces they covered. Yet they cannot by any

stretch of imagination be interpreted as a technical precondition

of that concept. Modular area division—as has

been made abundantly clear by the examples here cited—

preceded modular vault construction by centuries and

reached far beyond the realm of architecture into the layout

of the decorative pages of Christian service books. It has its

roots in a cultural frame of mind, not in technical conditions.

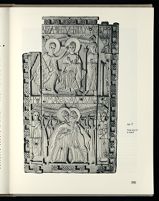

190.X GENOELS-ELDEREN DIPTYCH

190.Y

Shown same size

as original

BRUSSELS. MUSÉES ROYAUX D'ART ET D'HISTOIRE

[by courtesy of the Musées Royaux]

The monumentality of architecture in concept, execution, and fabric

may tend to overwhelm the scale of, and make distant, those objects that

men once handled and used in their daily pursuits. Tools, books, jewelry,

harness trappings, weapons, liturgical objects—with few exceptions they

are gone from us. The survivors, many of them precious then, as now,

lie in museums, remote from the purposes of their makers and rendered

exotic by their scarcity. Thus, the integration in spirit of such intimate

objects with monuments of architecture is somewhat difficult to achieve.

The many handicrafts that provided embellishment to daily life in a

monastic community such as was proposed by the Plan of St. Gall, has

been but lightly touched upon in this study. That works of art and

adornment were important to the community is undisputed. The Plan

has accommodations for making weapons and associated equipment,

saddlery and presumably other harness tack, and goldsmithing. Silversmiths,

lapidaries, and enamellers may have worked with armourer and

swordsmith. These crafts were housed with other facilities for more

ordinary work, in a pair of buildings in the southwestern tract of the

presumed site. Lay artisans were intended to reside in the community,

as is evidenced by comprehensive housing provided in the Plan.

Crafts that enhanced the praise of God by ornamentation of books,

vestments, and liturgical objects to assist in worship, were proper

activities for monks. Most notable were manuscript copying and

illumination, and ivory carving was likely among them. It is not

referred to specifically on the Plan of St. Gall, probably because its

execution did not require special facilities such as forges, smelters, and a

welter of noisy tools. The work of the ivory carver, silent and delicate,

often closely connected with all aspects of bookmaking, could be done

in a scriptorium, in company with scribes and illuminators.

The illustrated book cover is closely related to illuminations of the

Godescalc Gospels (781-783), earliest of the Court School manuscripts.

It has the same flatness of relief, the same delicate linearity, clearly

distinguishing it from the softly rounded forms and classicizing drapery

style of the later ivories of this school. The model must have been an

Early Christian ivory of Coptic or Syrian origin and representing a

style widely diffused in Merovingian Europe.

The front cover of the diptych shows Christ standing on the asp and

basilisk, flanked by two angels. The back cover displays the Annunciation

(upper register) and Visitation (lower register). Both covers are

pieced from several ivory plaques of different sizes. The work is

perforated and may have been mounted on a foil of gold leaf. The eyes

are inlaid lapis; interlace and step-patterns of the frames are clearly

influenced by insular art and stand in strong contrast to the perspective

illusionism of the two scenes. For references, see Braunfels, KARL DER

GROSSE, WERK UND WIRKUNG (exh. cat.), No. 534, pp. 345-46.

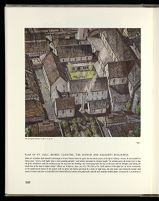

191. PLAN OF ST. GALL. MONKS' CLOISTER, THE CHURCH AND ADJACENT BUILDINGS

When St. Cuthbert built himself a hermitage on Farne Island, where he spent the last eleven years of his life in solitary retreat, he surrounded his

living space "with a wall higher than a man standing upright," and further increased its relative height "by cutting away the living rock so that

the pious inhabitant could see nothing except the sky from his dwelling, thus restraining both the lust of the eyes and the thoughts and lifting the

whole bent of his mind to higher things" (Bede, ed. Colgrave, 1940, 214-17). The Plan of St. Gall achieves a like effect for an entire community

in the sophisticated layout of the cloister with its egress and ingress governed by a body of rigid laws, the open inner court being the monks' only

access to nature and sun—a controlled and ordered island of nature with judiciously selected and carefully tended plants: PARADISUS CLAUSTRALIS.

On the abbey church of Gernrode see Grodecki, 1958, 24 and the

literature cited ibid., 40 note 19.

It is hard for me to understand that this fact should have been so

consistently overlooked in the entire authoritative literature on the Abbey

Church of Jumièges (Ruprich-Robert, 1889; Martin du Gard, 1909;

Lanfry, 1954; Michon alone dissenting in 1927). The evidence of

the once existing transverse arches is deeply engraved into the masonry

of the two clerestory walls and unmistakable. Even the latest discussion

of the church (Vallery-Radot, 1969, 132ff and Musset, 1972,

113-19) entirely disregards the problem of diaphragm arches, although a

foolproof case for their existence had already been made in a study by

C. Pfitzner published in 1933 (Pfitzner, 1933, 161).

For Hildebold's cathedral at Cologne see above, pp. 27ff; for the

abbey church of St. Riquier, above, pp. 169, 209, and 221.

"I suggest that the triumphal arch of the Early Christian basilica

and Carolingian church was the prototype for the diaphragm arches in

the nave proper. A diaphragm arch is, after all, only a triumphal arch

which has migrated to the nave of the church. Why go to Syria for a

prototype when one exists only a few feet away?" (Roger Cushing Aiken

in a graduate seminar report presented at Berkeley in the Spring Quarter

of 1970). The surprising thing about this observation is that it does not

seem to have been made before.

I am not aware of the existence of any reliable measurement studies

concerning the Cathedral of Speyer, and am only making a speculation.

For recent analysis of the masonry and construction sequence of Speyer

see the articles of Kubach, Christ and Bornheim in Festschrift, "900

Jahre Kaiserdom zu Speyer," ed. Ludwig Stamer, Speyer, 1961, and also

the comprehensive treatment of Speyer by Kubach and Haas in Die

Kunstdenkmäler von Rheinland-Pfalz, 3 vols., Berlin and Munich, 1972;

and Kubach, Der Dom zu Speyer, Darmstadt, 1972.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||