The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| II. |

| II. 1. |

| II. 2. |

| II.2.1. |

| II.2.2. | II.2.2 |

| II. 3. |

| III. |

| IV. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

II.2.2

THE CHURCH AS MODIFIED IN THE

LIGHT OF ITS CORRECTIVE TITLES

To reconstruct what the Church of the Plan would have

looked like had it been modified in the light of the corrective

titles is an intriguing historical task and has produced

a variety of different proposals. It is not surprising that no

agreement has ever been reached in this matter. The

attempt involves some delicate changes on which even

Carolingian architects might not easily have come to terms

with one another.

GEORG DEHIO (1887) & JOSEPH HECHT (1924)

One of the distinctive and historically most fascinating

features of the Church drawing is that it is constructed

according to a system of squares (fig. 61), exhibiting a

principle of spatial organization that became a guiding

feature in certain schools of the Romanesque, two centuries

later.[191]

To reduce the Church to the requested length of

200 feet implies the abandonment of the square schematism;

anyone who attempts to redraw the Church using

the measurements listed in the explanatory titles has made

this distressing discovery. Not wishing to totally relinquish

this feature Georg Dehio, who belonged to a generation of

architectural historians profoundly interested in the problem

of modular geometricity in medieval architecture,

retained the squares in the transept and in the fore choir.

By diminishing the interstices of the arcades of the nave

to the stipulated twelve feet, he then arrived at the compromise

length of 218 feet (fig. 130).[192]

Joseph Hecht, pursuing

similar lines of thought, arrived at a length of 224

feet.[193]

124. PARIS. ST. GERMAIN-DES-PRÈS

[after Deneux, 1927, 50, fig. 70]

125. PARIS. ST. PIERRE DE MONTMARTRE

[after Deneux, 1927, 50, fig. 71]

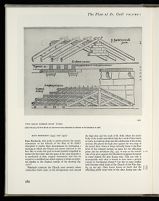

Two typical examples of the SPARRENDACH, a relatively steep-pitched

roof with supporting frames of narrowly spaced rafters in continuous

sequence, with light scantling, and braced internally but without purlins

or ridge beams.

126. ROME. ROOF OF OLD ST. PETER'S RECORDED IN 1694 IN

CARLO FONTANA'S TEMPLUM VIATICANUM ET IPSIUS ORIGO. Detail of engraving same size as original

[after FONTANA, 1694, 99]

In publishing this design of what he refers to as "the trusses which sustained the

roof over the nave of Old St. Peter's" (LE INCAUALLATURE, CHE SOSTUEUANO LI

TETTI DELLA NAUE MAGGIORE . . . DEL ANTICA BASILICA VATICANA) Carlo Fontana

(1634-1714), disciple and collaborator of Lorenzo Bernini and architect in charge

of the Pontifical Office of Architects and Engineers, informs his readers that his

engraving was made after an "accurate drawing" (UN GIUSTO DISEGNO) tendered

him by an "informed person" (UNA PERSONA DILETTEUOLE); and that it was

because of the extraordinary constructional "sophistication" (INTELLIGENZA) as

well as the soundness of the timbers employed in these trusses that the roof of the

Constantinian basilica survived intact for so many centuries—to the extent that

when finally taken down, it was found to be in such good condition that its timbers

could be reassembled to sustain the roof of the Palazzo Farnese.

If timbers from the roof of Old St. Peter's were re-used in the Palazzo Farnese

(1546-1589) they must have come from the western half of the nave dismantled

by Bramante (1502) to make room for the construction of New St. Peter's. The

eastern half of the nave (closed off from the construction site by a provisional wall

under Paul III, 1534-1549) was demolished only in 1606 to make room for Carlo

Maderna's westward elongation of New St. Peter's. The roof timbers of this

portion were also re-used, this time for the Palazzo Borghese (1605-1621).

The names of the component members of the truss shown in Fontana's engraving

are enumerated on two scrolls which form part of the drawing. On these the tie

beams are referred to as CORDE MAGGIORI (B), the collar beams as CORDE

MINORI (C), the rafters as PARADOSSI (D), the center post suspended from the

apex of the truss as traue pendente adVso di monaco (E).

During the 12th to 13th centuries of its existence, the roof of the Constantinian

basilica of Old St. Peter's was, not surprisingly, in need of numerous repairs. A

complete account of them, including what in the sources is referred to as a "renovation"

by Pope Benedict XII (fecit fieri de novo tecta huius Basilicae sub anno

1341) is given by Michele Cerrati in Tiberii Alpharini, "De Basilica Vaticana

Antiquissima et Nova Structura" (STUDI E TESTI vol. 26 Rome, 1914, 13 note 2;

brought to my attention by my colleague Loren Partridge). There is no compelling

reason to presume that Benedict's renovation involved any basic changes in the

roof's design.

Fontana's rendering of the trusses of Old St. Peter's is in complete accord with

that which Vitruvius recommends for broad spans, except that all of the principal

members of the truss are doubled, and that the tie beams are fashioned in two

pieces, joined midway by an overlapping scarf joint. Owing to the extraordinary

width of the nave of Old St. Peter's (23.6 3m.), two-piece tie beams were necessary

since it would have been hard to find trees of sufficient height to yield single timbers

to span the whole space. Doubling all of the principal members was an extremely

wise constructional feature—probably the primary contribution to the longevity

of the Constantinian trusses—which evolved from the strategic function made of

the TRAVE PENDENTE. The scheme is a laminative one; a kind of truss-sandwich

is formed in which the structural components are assembled and joined in a function

that yields, in effect, a "pair" of trusses, but which is really a single homogeneous

creation of remarkable simplicity and purity of concept—revealing a mastery of static

mechanics that transcends Vitruvius and commands admiration today. Yet the design

does not seem to have found general acceptance. On the contrary, a medieval carpentry

truss, when it is impressive, gains our attention rather by its quaintness, its

intricacy of joinery and the complexity of its members.

The construction is ingenious. Transmitting the entire roof load to the two outer ends

of the tie beams, the principal rafters D-D are in compression and thus act as

columns as well as beams. Column action augmented by the deflection of beam

action is resisted by the horizontal strut C-C (collar beam) which functions in

compression. These minor chords support the rafter pairs midway in their span, a

construction that reduces the effective length of the rafters to approximately one-fourth

the nave span. Strut C-C is supported at mid-point by the vertical member

E-E (MONACO) which concurrently serves as a tension member to prevent sag in

the great lower chords. The scarf joint of these tie beams, tabled, locked, and

girdled by iron bands, prevents them from separating in the horizontal plane. In

contemplating the brilliance and simplicity of the design, remember that the wall-to-wall

span was above 84 feet—reflecting a state of theory of mechanics and

knowledge of structure existing in the 4th century!

127. TWO BASIC ROMAN ROOF TYPES

[after Vitruvius, Fourth Book on Architecture; interpreted by Barbaro in his translation of 1556]

HANS REINHARDT (1937 and 1952)

Hans Reinhardt, who tends to under-evaluate the square

schematism of the Church of the Plan of St. Gall,[194]

attempted to resolve these discrepancies by developing a

drawing in which the Church was shown reduced to 200

feet. But to attain this goal he found himself compelled to

reduce the fore choir and the space of the crypt beneath it

to one-fourth of their original dimensions, and thus he

arrived at a modified plan which appears to retain no spiritual

kinship to the original concept of the drawing (fig.

131).[195]

Reinhardt contracts the Church most severely where

contraction hurts most: in the all-important area around

the high altar and the tomb of St. Gall, where the entire

body of the monks assembled daily for a total of four hours

or more, in common chant and the celebration of the divine

services. He placed the high altar against the very edge of

the raised choir, where it drops vertically down to the floor

level of the transept leaving no space for the officiating

priest and his attendants (fig. 132). A step on the eastern

side of the altar suggests that Reinhardt imagines the priest

to stand behind the altar facing west. This not only is

incompatible with what is known to have been a general

custom in Carolingian liturgy,[196]

but also in open conflict

with fourteen other altars in the Church of the Plan (figs.

84, 93 and 99). Their layout leaves no doubt that the

officiating priest stood west of the altar, facing east; the

128. SYRIA, BATUTA CHAPEL. PORCH, SOUTH SIDE

[courtesy Princeton University Archaeological Expedition to Syria]

leaves no doubt on this score.

One feels equally puzzled about Reinhardt's modification

of the crypt. The drafter of the Plan provided the

monastery with two crypts with different but complementary

functions. One is an outer corridor crypt in the

shape of a crank, which takes the pilgrims and the other

secular visitors to the tomb of St. Gall. The other is an

inner crypt which lies beneath the high altar and is reached

from the crossing through a passage marked accessus ad

confessionem, between the two flights of steps that lead up

to the fore choir (fig. 99). Being accessible from an area

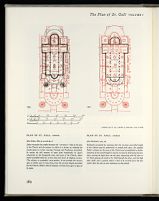

130. PLAN OF ST. GALL. CHURCH

[after Dehio, 1887, pl. 42 and fig. 2]

Dehio reconciles the conflict between the "corrective" titles of the plan

of the Church and the manner in which it is drawn, by reducing the

arcade spans to 12 feet. Leaving Transept and Presbytery untouched,

he retains the full measure of space (and incidentally its square

schematism in the liturgically most vital part of the Church, where

monks assembled daily for no less than four hours of religious services.

This solution is acceptable—even perfect—if one excludes the western

apse, as Dehio seems to have done, from the 200-foot length prescribed

for the Church. Dehio's church measures 218 feet from apex to apex of

its apses.

131. PLAN OF ST. GALL. CHURCH

[after Reinhardt, 1952, 20]

Reinhardt proceeded by assuming that the 200-foot prescribed length

of the Church must be understood to include both apses. He adopted

Dehio's solution for the nave of the Church and accomplished a further

reduction of the overall length to exactly 200 feet by eliminating the fore

choir, moving the high altar into the apse, dispensing with the altar of

St. Paul, placing the tomb of St. Gall beneath the altar, and the high

altar itself, into a position where it had to be serviced from the east

rather than the west as was customary in this period.

129. SYRIA. BRAD CONVENT. PEDIMENT OF PORCH

[after Butler, 1929, 199, fig. 201]

Had Forsyth not discovered the 6th-century roof of St. Catherine's on Mt. Sinai, Brad and Batuta (fig. 128) would be sole evidence for

reconstructing the design of timbered roofs in Early Christian Syria. St. Catherine's roof is still functioning, in perfect condition. See The

Monastery of St. Catherine at Mt. Sinai, 1973.

have been a hall crypt providing the monks with prayer

space around the tomb of St. Gall.[197] Reinhardt eliminates

this confessio altogether and thus creates a spatial vacuum

in one of the most spiritually vital spots of the Church.

From a liturgical and functional point of view the

removal of the fore choir is fatal. Moreover, it is devastating

in its effect on the subsidiary spaces of the Sacristy and the

Scriptorium, which are built against the fore choir and, like

the latter, each cover a surface area of 40 × 40 feet. What

does Reinhardt propose to do with them? To reduce them

proportionately would render them unusable;[198]

to retain

them as originally planned would amount to an aesthetic

degradation of the apse which seems incompatible with its

liturgical and architectural function.

Reinhardt's proposal also seems unsuitable in general

historical terms. The interposition of a separate spatial unit

between apse and transept is one of the new and original

features of Carolingian architecture. It appeared in

Neustadt-on-the-Main shortly after 768-769 (figs. 116, 133);

in the abbey church of St. Riquier (Centula) between 790799

(fig. 135); in the church of Vreden around 800 (fig. 136);

in the cathedral of St. Mary and St. Peter of Cologne, prior

to the death of its founder, Archbishop Hildebold, d. 819

(fig. 139); in St. Mary at Mittelzell on Reichenau, as rebuilt

by Abbot Haito between 806 and 816 (fig. 134); and in the

abbey church of Hersfeld, if Groszmann's reconstruction is

correct, between 831 and 851.[199]

The primary motivation

for this new spatial entity was, as Thümmler has correctly

pointed out, the desire to isolate and strengthen the importance

of the high altar, at which the choral services were

held, and to provide more space for the officiating clergy.[200]

The increasing dimensions of the crypt, and the latter's

division into an outer corridor crypt for the pilgrims and an

inner confessionary for the monks, is directly related to this

development. Both of these innovations were responses to

pressing liturgical needs.

On altar orientation in Carolingian times, see Braun, I, 1924, 411ff.

and Otto Nussbaum's exhaustive study on The Position of the Officiating

Priest at the Christian Altar Prior to the Year 1000, which was not

published when these lines were written. Nussbaum's analysis of the

altarspace in Carolingian and Proto-Carolingian churches of Germany,

France and Switzerland has proven without any shadow of doubt that

from the end of the seventh century onward the officiating priest stood

between the altar and the populace facing the altar eastward. This is the

position in which he is shown on the ivory covers of the Drogo Sacramentary,

in scenes where he celebrates the Mass or is engaged in other

phases of the religious service. From a reading of the Frankish edition of

the Ordo Romanus I, issued during the first half of the eighth century (as

well as all later editions of this treatise) Nussbaum infers that when the

service was performed by the bishop in person, the latter had to walk from

his cathedra in the apex of the apse westward around and to the front of

the altar where he celebrated the Mass with his back turned toward the

worshipping crowd. (See Nussbaum, 1963, 305ff and summary of this

chapter, 358-66).

As correctly observed by Walter Boeckelmann, 1956, 127: "Sakristei,

Schreibstube und Bibliothek schrumpfen zu schmalen Kammern

zusammen . . . der korrigierte Plan kann nicht mehr als exemplarisch

gelten."

For Neustadt-on-Main, see Boeckelmann, 1951, 43-44 and 1956,

38ff and 58ff. For St. Riquier (Centula), see Gall, 1930 and E. Lehmann,

1938, 109. For Vreden see Winkelmann, 1953, 304-19. For the Carolingian

church of Cologne, see Weyres, 1965, 384-423; and the literature

quoted above on p. 26, note 4. For St. Mary in Mittelzell, see Reisser,

1960, and Christ, 1956. For Hersfeld, see Groszmann, 1955, 9, and

Feldkeller, 1964, 1-19.

ARGUMENTS IN FAVOR OF

DEHIO'S INTERPRETATION

It is easy to understand why Dehio was reluctant to

undertake any changes in the eastern parts of the Church

and took the step, for which he was subsequently so

severely criticized, of making the Church a little larger (218

feet) than the stipulated 200 feet. However, there remains

the question whether Dehio is really guilty of such a compromise.

His reconstruction may in fact be based upon a

more accurate interpretation of the title which prescribes

the reduction. Dehio's critics interpret the propositional

phrase AB ORIENTE AD OCCIDENTē to mean "From the

apex of the eastern apse to the apex of the western apse."

There is no assurance whatsoever that this is in fact what

the title meant to convey. The first five letters of the phrase,

AB ORI, are inscribed into the eastern apse, which means

that this apse was a component part of the designated

length. But the inscription does not run into the round of

the western apse; it stops in the westernmost bay of the

nave with the numeral .cc. Literally interpreted this would

mean that the western apse was not meant to be included

in the designated length of 200 feet. If it was not, then

Dehio's reconstruction (fig. 130) would run only 8 feet

132. PLAN OF ST. GALL

CRYPT & ALTAR SPACE, Reinhardt's Interpretation

[after Reinhardt, 1952, 20]

Eliminating the fore choir and moving the high altar into the apse

would have reduced space occupied by monks during divine services to

less than half that foreseen in the Plan. In addition to incongruities

described in fig. 131, this would have led to congestion of disastrous

proportions in this most heavily used part of the Church.

12 feet = 108 feet; crossing unit = 40 feet; fore choir =

40 feet; apse = 20 feet. Total = 208 feet)—close enough

to be acceptable; and acceptable without any shadow of

doubt, if the radius of the eastern apse were shortened from

20 feet to 12 feet.[201]

It is imperative, in this context, to draw attention to the

fact (entirely disregarded in previous discussions of this

subject) that the reconstruction proposed by Georg Dehio

appears to conform, indeed, with the manner in which

Abbot Gozbert and his builders interpreted the Plan when

they rebuilt the church in 830-836, as August Hardegger

inferred from the measured architectural drawings made of

the church by Pater Gabriel Hecht, in 1725/26, when

much of the Carolingian fabric of the church was still

identifiable.[202]

Throughout the entire width and length of the Plan the scribe takes

the utmost care in placing his titles, so that they exactly correspond to the

area which they describe. Amongst the total of 340 separate entries there

is not a single one where this relationship would be ambiguous or

susceptible to misinterpretation.

For more detail on this subject see our chapter "Rebuilding of the

Monastery of St. Gall by Abbot Gozbert and his Successors," II,

319ff. The results of excavations of the remains of Gozbert's church

under the pavement of the present church, conducted by H. R.

Sennhauser, were not known to me when this chapter was written. From

information personally received from Dr. Sennhauser, I infer that his

findings confirm the main conjecture here advanced, viz. that the overall

reduction in the length of the church was accomplished through a radical

shortening of the nave, and not by diminishing the surface area of

transept and choir.

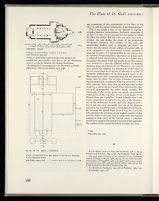

WOLFGANG SCHÖNE (1960)

By far the most radical attempt to reconcile the drawing SAVIOUR'S CHURCH (after 768/69). PLAN [after Boeckelmann, 1952, fig. 3] Although the early date of this church has recently been questioned

of the church of the Plan of St. Gall with that of its corrective

explanatory titles was that which Wolfgang Schöne

published in 1960.[203]

Schöne not only shortened the church

to the desired 200 feet, but applied the same reduction to

all the other buildings of the Plan. However, in advancing

this theory he either overlooked or disregarded the fact that

the same proposition had already been discussed and convincingly

133. NEUSTADT-AM-MAIN

(see Vorromanische Kirchenbauten, 1965, 233), with other

Carolingian churches of similar plan (fig. 153.B) it demonstrates the

liveliness of the concept of the square-divided Early Christian quincunx

church (figs. 144-149) with tower-surmounted crossing and extended

altar space.

Arens, who pointed out that if one were to redraw the Plan

according to the measurements given for the length of the

Church (i.e., 200 feet), the Cloister and all of the service

structures of the Plan would be too small to perform their

designated functions.[204]

My own analysis of the scale used in designing the Plan

confirmed this view. Were the Plan redrawn in this manner

not only would the monks, including the abbot and the

visiting noblemen (i.e., Monks' Dormitory, Abbot's House,

and House for Distinguished Guests) no longer fit into

their beds, but the Refectory of the Monks would be too

small to seat the full contingent of monks, the horses would

lack the required floor space to stand in their stables, and

the workmen could not carry out their respective crafts and

labors.[205]

The most decisive counter argument, however, to

Schöne's interpretation of the Plan is to be found in a

statement made by a man who lived at the time when the

Plan was drawn. In his commentary on the Rule of St.

Benedict, written around 845 in the monastery of Civate,

Hildemar, a monk from Corbie, declared that in his days

"It was generally held that the cloister should be 100 feet

square and no less because that would make it too small."[206]

Schöne reduces it to a little less than 67 × 67 feet. It is

historically incongruous to assume that a scheme of paradigmatic

134. REICHENAU-MITTELZELL

HAITO'S CHURCH (CONSECRATED 816)

[after Reisser, 1960, fig. 285]

Built by the "author" of the Plan of St. Gall, between 806-817 (but

the nave perhaps not before 811), this church continues the tradition of

St. Riquier with its extended altar space and tower-surmounted

crossing. (Also see figs. 117 and 171 for comment on its alternating

supports, and its underlying modular concepts.)

fall by one-third below what at the time was

considered to be the lowest suitable limit.

Schöne, 1960, 147-54. Thomas Puttfarken, in an article not

available when this chapter was written (Puttfarken, 1968, 78-95)

expressed similar views. My objections are the same as those here

proffered against Schöne's interpretation. Both studies tend to give

insufficient weight to the carefully argued views of previous students of

the Plan (Arens, 1938; Boeckelman, 1956).

See my analysis of the Dormitory, below, pp. 249ff; the Abbot's

House, below, pp. 321ff; the House for Distinguished Guests, below, p.

155ff; and the Refectory, below, pp. 267ff.

Wolfgang Hafner has drawn attention to this fact in an interesting

article in Studien, 1962, 177-92; see below, p. 246, for a more detailed

discussion of this passage.

ADOLF REINLE (1963-64)

The reconstruction of Adolf Reinle (fig. 137), because of ANGILBERT'S ABBEY CHURCH (790-799) [after Achter, 1938, fig. 86] This is the first great Carolingian church built on a Latin cross plan,

his radically different interpretation of the axial explanatory

title of the Church, occupies a position entirely apart from

those of any of the previous students of the Plan. Translating

the axial title of the Church "AB ORIENTE AD OCCIDENTE[M]

PED .CC." in the sense of "THIS PLAN IS DRAWN

AT THE SCALE OF 1:200," he felt himself under no compulsion

to reduce the Church to a length of 200 feet, as so

many others had tried to do. He rather endows it with its

full length of 300 feet. However, in adjustment to the title

which designates the intercolumnar interstices of the

arcades of the nave to be 12 feet, Reinle consequently

increased the number of arcades from nine to fifteen.

Reinle draws support for this interpretation from the

observation that arcades of a span of 20 feet (6.8 m.) are

not known to have existed in any of the large colonnaded

basilicas of the first millennium.[207]

This being as it is, he

concludes "we must assume that the columnar order of the

Church of the Plan of St. Gall is rendered in a schematic

manner in logical explication of the system of squares which

controls the Plan of the Church."[208]

He categorically rejects

135. ST. RIQUIER (CENTULA)

with extended choir and a monumental westwork. The church is so well

described in an 11th-century chronicle that its general outlines can be

reconstructed with fair certainty. Achter accounts for irregularities that

reflect the Carolingian predecessor of the Gothic church. For her other

views of this building see figs. 168 and 196.

136. VREDEN. PLAN

CHURCH OF SS FELICISSIMUS, AGAPITUS, & FELIGITAS

[after Thummler, 1953, 306]

Vreden is a three-aisled cruciform basilica with westwork and

extended choir, plus an annular crypt, built ca. 800 (W. Winkelmann,

1953) or ca. 839 (H. Claussen). See Claussen-Winkelmann,

"Archäologische Untersuchungen unter der Pfarrkirche zu Vreden

(Vorbericht)," Westfalen XXXI, 1953, 304ff.

137. PLAN OF ST. GALL. CHURCH

REINLE'S INTERPRETATION OF THE CHURCH OF THE PLAN AS MODIFIED

BY ITS CORRECTIVE TITLES

[after Reinle, 1962/3, 100]

SCALE 1/64 INCH = ONE FOOT [1:768]

Church with the square schematism of the Romanesque.[209]

This is too simple a way, in my opinion, to explain a

complex historical phenomenon. Columnar interstices of

20 feet, it is true, are not attested for the period in which

the Plan was drawn. But this does not mean that such a

solution was not within the grasp of an imaginative

Carolingian architect. Our analysis of the scale and

construction method used in designing the Plan[210]

has

shown that the author of this scheme proceeded with an

acute awareness of the dimensional realities involved in

whatever he drew. It is inconceivable, in my opinion, that

an architect whose punctilious observance of spatial needs

is reflected in the dimensioning of even the smallest detail

throughout the entire width and length of the Plan, should

have reverted to a radically different method of rendering

when he drew the Church of the Monastery and should

have spaced the columns at a distance of 20 feet when in

fact he meant them to be placed at intervals of 12 feet. A

consistent interpretation of the dimensional layout of the

Plan permits no other conclusion than that the draftsman

meant what he drew. Nor is there evidence to presume

that the instruction to make the columnar interstices 12 feet

wide stemmed from fears that arcades spanning 20 feet

would be a constructional hazard. Our reconstruction (figs.

107-110) demonstrates this point clearly enough. The

shortening of the arcade spans was simply an inevitable

consequence of the reduction of the overall length of the

Church from 300 to 200 feet. It dealt a deadly blow to the

square schematism as applied to the nave of the Church—

one of the draftsman's favorite and most original ideas—

but it was the most reasonable way out of the dilemma

caused by the overall reduction of the length of the Church.

By reducing the spatial depth of each bay, the corrective

title permitted the retention of the original number of altar

stations, while at the same time it safeguarded the original

concept in those parts of the Church where a reduction

would have impaired the primary function of the sanctuary,

the conduct of the sacred services in transept and choir.

PLAN OF ST. GALL

137.X CENTULA

(ST. RIQUIER)

see also page 185 and figs. 135, 168, and 196

141. ROME. OLD ST. PETER'S

[after Jongkees, 1966, 34, Pl. I and II]

The church's inner length was 112m (368′), its height 84m (276′), and its width

58m (190′). Probably begun after 324 and finished by Constantine's death in 377,

its precise dates are unknown.

138. FULDA

[after Groszmann, 1962, 351, fig. 5]

Ratger's church of 802-817. Precise measurements unknown

139. COLOGNE

Hildebold's church of SS Peter and Mary

[after Weyres, 1966, 408, fig. 10]

140.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||