The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| II. |

| II. 1. |

| II. 2. |

| II.2.1. |

ROOF COVERING |

| II.2.2. |

| II. 3. |

| III. |

| IV. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

ROOF COVERING

The customary material used for covering the roofs of

Carolingian churches was tile or lead. The distinction is

not always clear, as the term tegula (classical Latin for

"ceramic tile") is used for both. However, it is probably

safe to assume that when tegula is used without the qualifying

adjective plumbea, it stands for tile.

When Benedict of Aniane founded his first monastery at

the banks of the stream of that name, he covered the

building "not with red-gleaming tiles, but with thatch"

(non tegulis rubentibus, sed stramine).[184]

Conversely, when he

rebuilt the monastery in 772, "he covered the houses not

with thatch, but with tiles" (non iam stramine domos, sed

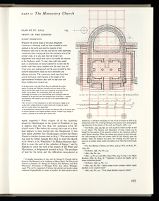

123. PLAN OF ST. GALL

CRYPT OF THE CHURCH

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

Whatever the precise shape of the space designated

CONFESSIO it obviously could not have exceeded an area

confined to the north and south by masonry of the

Presbytery walls and to the west and east by walls separating

CONFESSIO from crossing and from the transverse arm of the

corridor crypt. It is also clear that the Crypt's two

longitudinal arms would have come to lie outside the masonry

of the Presbytery walls. To clear these walls they would

each, in construction, be moved outward by 2½ feet; but the

builder could have easily complied with this need, since the

Crypt arms were underground and the space invaded by their

outward displacement would not have diminished any

adjacent structure. The CONFESSIO surely must have been

covered with groin vaults because of the weight of the

superincumbent Presbytery floor with its high altar and

heavy loading from constant use.

In the plan shown to the right Ernest Born has subdivided the 40-foot

squares of crossing and Presbytery internally each into sixteen 10-foot

squares and the latter again (in the areas occupied by the crypt) each into

sixteen 2½-foot squares. Our reconstruction shows how easily and

convincingly the masonry of an actual building can be developed within the

framework of the grid that forms the conceptual basis of the Plan — masonry

and foundation solid enough to carry the load of the superincumbent walls

of the Church.

The CONFESSIO is here interpreted as an inner hall crypt of roughly 20 by

30 feet with a ceiling formed by six groin vaults each covering the surface

area of a 10-foot square (100 square feet).

In the interpretation illustrated here the gray tint indicates walls of the church above

in locations depicted on the original document, and the U-shaped crypt passage or

corridor is presumed to be covered with a barrel vault.

issued by Charlemagne at the synod of Frankfurt in 794,

it appears that tile was then the customary cover for

church roofs.[186] But before the century had come to a close,

lead appears to have moved into the foreground. It was

with tegulis plumbeis that Charlemagne covered the Palace

Chapel at Aachen (consecrated in 805).[187] The same material

was used by Abbot Ansegis (807-833) to cover the church

of St. Peter's at St. Wandrille,[188] by Bishop Hincmar (845882)

to cover the roof of the cathedral of Reims,[189] and by

Einhard to cover the roof of his church of SS. Peter and

Marcellinus, at Seligenstadt (started in 827). The purchase

of lead for the latter and the difficulties encountered in

written to an unidentified abbot:

I am speaking about the conversation we had when, meeting in the

Palace, we talked about the roof of the blessed martyrs of Christ.

Marcellinus and Peter, which I am now trying to build, although

with great difficulty, and a purchase of lead for the price of 50

pounds was agreed between us. But although work at the basilica

has not yet reached the point where I should be concerned with the

necessity of building the roof, yet it always seems that we should

hasten, because of the uncertain span of mortal life, to complete the

good work we have begun, with God's help.[190]

Ibid., 11, No. 41; and Mon. Germ. Hist., Leg. II, Cap. I, ed. Alfred

Boretius, 1883, 76, chap. 26: "Lignamen, et petras sive tegulas, qui in

domus ecclesiarum fuerint."

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||