The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| II. |

| II. 1. |

| II. 2. |

| II.2.1. |

CROSSING |

| II.2.2. |

| II. 3. |

| III. |

| IV. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

CROSSING

The reconstruction of the crossing (figs. 108-112) has been

a matter of some controversy and, in fact, permits different

interpretations. Two basic questions present themselves

immediately: first, was the crossing surmounted by a

tower; and second, were the roofs of nave and transept of

equal height? The first of these two questions must, I

think, be answered in the negative. The second does not

admit a clear-cut answer.

Crossing towers have been assumed in Fiechter-Zollikofer's

and Gruber's reconstructions of the Church of

the Plan (figs. 277 and 282).[136]

Historically, this is a perfectly

feasible solution. Square towers, rising from crossings

produced by the interpenetration of two volumes of space

of essentially equal height, existed in the Abbey Church of

St.-Denis, constructed under Abbot Fulrad, 750-755;[137]

in the basilica of Neustadt-on-the-Main after 768/69[138]

(fig. 116); in the Abbey Church of St. Mary's on the island

of Reichenau, consecrated by Bishop Haito in 816[139]

(fig.

117); and in the church of St. Martin at Angers, end of

ninth century.[140]

But the Plan of St. Gall does not call for a

tower. In any of the other buildings, wherever a structure

was composed of two stories, the maker of the Plan indicated

this by an explanatory title, defining the function of

the lower story with a phrase that begins with the adverb

infra, "below," and that of the upper story by a phrase

that begins with the adverb supra, "above."[141]

Had he

meant the crossing to be surmounted by a tower, he could

have expressed his intention with a statement such as infra

chorus, supra turris—"below, the choir; above, a tower."

The fact that he did not do this suggests that a crossing

tower was not intended.

With regard to the respective heights of nave and transept,

the traditional view has been that they were of equal

height and that the crossing was framed by boundary

arches on all four sides, rising from wall pilasters and from

cruciform piers (figs. 107-110). It is in this manner that

the crossing unit was interpreted by Friedrich Seesselberg

(1897), Georg Dehio (1901), Wilhelm Effmann (1899 and

1912), Friedrich Ostendorf (1922), Joseph Hecht (1928),

Ernst Gall (1930), and Edgar Lehman (1938).[142]

It is also

the view that underlies the graphical reconstructions of the

Church, published by J. R. Rahn (1876), Joseph Hecht

(1928), H. Fiechter-Zollikofer (1936), and Karl Gruber

(1937 and 1952).[143]

However, this explanation of the Plan was questioned by

Hermann Beenken and by Samuel Guyer,[144]

who felt that

to interpret the supports in the corners of the crossing of

the Church as piers and pilasters was not permissible,

because the symbol used for these members (a square with

a circle inscribed) is identical with that which is used for

the nave columns. Beenken's and Guyer's criticism is based

on the arbitrary assumption that the square with the

inscribed circle could only have had the exclusive meaning

of "column." A more circumspect analysis of the use and

distribution of this symbol discredits this view. In the

Monks' Refectory, the House for Distinguished Guests,

and the Abbot's House, the same sign is used to designate

used to designate a lectern (analogiu). In the room for the

preparation of the holy bread and the holy oil it stands for

"oil press," in the Monks' Privy, for "a table with a

lantern" (lucerna), and in the hypocausts of the Monks'

Warming Room, the Novitiate and the Infirmary, it stands

for "chimney stack" (euaporatio fumi). It seems absurd to

persist on a course of reasoning which is based on the

supposition that the designer of the Plan of St. Gall was

unaware of the distinction between a pier and a column

because he used the same symbol for both of these structural

members. To do so would be no less incongruous than

to accuse him of having designed a clerestory wall whose

arcades rested on cupboards, lecterns, oil presses, lantern-carrying

tables, or chimney stacks.[145]

It is obvious that in drawing the structural members of

his church, the architect availed himself of a symbol whose

meaning was not limited to "columns," but could be understood

in the more general sense of "arch-support," leaving

it to the builder of the Church to interpret this sign as its

architectural context required, either as a freestanding

column (as in the nave arcades) or as an engaged half column

(wherever it is shown as being part of a wall), or as cruciform

piers (as in the four corners of the crossing). In order

to preclude any further misunderstandings I should like to

pursue more closely the evidence furnished by the Plan

itself.

The Plan indicates clearly that the supports which stand

in the western corners of the crossing must have been

shaped in such a way as to receive the arches of the easternmost

arcade on either side of the nave, as well as the arches

of the openings which connect the aisles with the transept.

Furthermore, they must have been able to receive on a

higher level the springing of the triumphal arch. The

existence of the triumphal arch cannot be proven on the

basis of the linear layout of the Plan, but its presence is

mandatory in a building of this size for obvious constructional

reasons.

The square symbols with the inscribed circles in the two

eastern corners of the crossing postulate the existence in

these places of engaged pilasters on columns, that make

sense only if we assume that they served as footing for

either a transverse arch, which separated the crossing from

the fore choir, or two longitudinal arches thrown across the

transept arms in prolongation of the nave walls. One of these

two assumptions is obligatory, but the fact that only one

of them can be established compellingly does not preclude

the other. The Plan does not provide us with any evidence

that would warrant dismissing the possibility that the

Church was meant to have had an arch-framed crossing

(fig. 110).

As for the elevation of this crossing unit of the Church of

the Plan, it is futile to speculate whether it belonged to the

fully developed type with arches of equal height, which

became a standard feature of western architecture at the

period of the Romanesque, or whether it belonged to any

PLAN OF ST. GALL

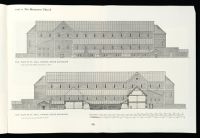

111.A CHURCH. NORTH ELEVATION

111.B CHURCH. SOUTH ELEVATION

Because of the surrounding buildings, no one standing on the

monastery grounds would have been able to entirely encompass

these two magnificent views of the Church. They strikingly

portray the antinomy and balance between directional thrust and

inward-turning that characterizes Carolingian double-apsed

churches of this type.

One may feel perplexed by the aesthetic kinship of these two-apsed

Carolingian churches—not so much by such unidirectional classics

of Early Christian architecture as Old St. Peter's (fig. 141) or

St. Paul's Outside the Walls (fig. 81) upon which their layout is

based (cf. below, p. 187ff); but rather with the pagan imperial

prototypes of these great palaeochristian transept churches, the

Roman market halls, many of which had apses at each end; and

most of which had attached to one broad side (as in the case of the

Church of the Plan of St. Gall) an open, galleried court through

which the building was entered laterally rather than on axis

(basilica of Trajan, fig. 239; Severan basilica at Lepcis Magna,

fig. 159; basilica of Silchester, fig. 202).

The Church of the Plan of St. Gall is a sophisticated combination

of both concepts. It is directional like the churches of the two

prime apostles, because the transept and presbytery, in the

heaping-up of their spatial masses, make it clear that the architecturally

most prominent part of the church, and its liturgical

focus, is its cruciform eastern end. This effect is emphasized in the

interior, through the raising of the floor level of the Presbytery

over the level of all of the other parts of the church; and on the

exterior, through the attachment to the two transept arms, on

either side of the Presbytery, of two double storied lean-to's, one

containing Sacristy and Vestry (south side) the other Scriptorium

and Library (north side).

Yet this directionalism has no starting point, because the church

has no façade. Instead it faces the outside world with a counter

apse which binds its spatial energies inward, blocking access to the

nave, and channeling visiting laymen in a semicircular movement

around it to aesthetically insignificant secondary entrances in the

aisles (cf. caption to fig. 82).

Double apsed-churches (cf. below, pp. 199ff) were common in the

palaeochristian architecture of North Africa, but rare in the

Italian homeland. Recent studies have shown that they also were

very common in Visigothic Spain (for a brief review see the

article Hispania in Reallexikon zur Byzantinischen

Kunst) which may have played a more important role in transmission

of this motif to the Carolingian world than has hitherto

been admitted or recognized.

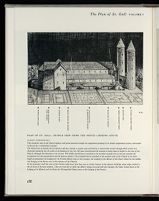

112. PLAN OF ST. GALL. CHURCH SEEN FROM THE NORTH LOOKING SOUTH

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

This broadside view of the Church displays with great pictorial strength the magnificent grouping of its slender longitudinal masses, intercepted

in the east by a monumental transept.

The Church has no façade, but its entrance side has, instead, a counter apse encircled by a semicircular atrium through which visitors are

channeled sidewards into the aisles of the building (cf. fig. 82). We have reconstructed the transept as being equal in height to the nave of the

Church, although this dimension is not certain. The double-storied lean-to attached to the northern transept arm in the east contains the

Scriptorium (on the ground floor) and the Library (above). The extended lean-to attached to the northern aisle of the Church in its entire

length accommodates the Lodging for the Visiting Monks (next to the transept), the Lodging of the Master of the Outer School (in the middle,

and Lodging of the Porter next to the entrance of the Church).

In the monastery itself this view of the Church could never have been seen in totality because of the adjacent buildings whose ridge reached to

the sill level of the nave windows. They are from left to right: the Abbot's House (co-axial with the transept), the Outer School (next to the

Lodging of its Master) and the House for Distinguished Guests (next to the Lodging of the Porter).

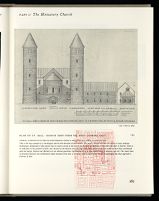

113. PLAN OF ST. GALL. CHURCH SEEN FROM THE WEST LOOKING EAST

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION [after the model displayed at Aachen in 1965]. ELEVATION TAKEN ON SECTION X-X

This is the only example of a Carolingian church with detached circular towers. The motif is unique and does not appear in later medieval

architecture. Explanatory titles denote that its towers carried at the top of one the altar of Michael, of the other, the altar of Gabriel. There is

no indication of the presence of bells, and, because of the distance from the high altar, their sound in any case could not have been coordinated

with the liturgy. Gabriel and Michael are the celestial guardians representing forces of light against those of darkness and evil. The towers have

no practical function, but symbolically might announce from afar to travellers (and at close range almost threateningly) that they approach a

Fortress of God.

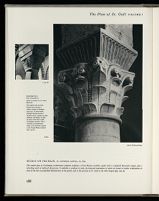

115.X REICHENAU-MITTELZELL

HAITO'S CHURCH OF ST. MARY

(806-816)

This capital from the main

arcades was re-used in a

column ascribed to Witigowo

(985-997). Its floral motifs,

although distantly based on

classical sources, represent in their

simplicity and flatness of relief

an early, rather than a high

Carolingian tradition. One is

reminded of developmental

stages of the Godescale Gospels

or the Genoels-Elderen diptych

(Fig. 190.X).

114. HÖCHST-ON-THE-MAIN. ST. JUSTINIUS, CAPITAL, CA. 834

This superb piece of Carolingian architectural sculpture combines a Greco-Roman acanthus capital with a strigilated Byzantine impost, plus a

refreshing touch of medieval abstraction. It embodies a synthesis of style, the historical ingredients of which are found in similar combinations in

some of the most accomplished illuminations of the period, such as the portrait of St. Luke in the Ada Gospels (fig. 184.A)

115 ST. GALL CAPITAL.

EXCAVATED BELOW THE PAVEMENT OF THE PRESENT CHURCH

CAPITAL FROM GOZBERT'S ABBEY CHURCH (830-837)

[after Sennhauser, "Zu den Ausgrabungen in der Kathedrale, der ehemaligen

Klosterkirche von St. Gallen," Festschrift zum 70. Geburtstag von Architekt

Hans Burkard, Gossau 1965, 109-116.]

More classicizing in the detail of its design than the capital of Höchst,

opposite, this one nevertheless seems to project a touch of weariness with

the classical tradition, clearly lacking stylistic firmness and sophistication

of the Höchst capital.

The capital, presumably from the columnar order of the nave arcades of

Gozbert's church, was re-used in the masonry of the foundations of the

Gothic choir built by abbots Eglolf and Ulrich VIII, between 1439 and

1483 (II, p. 326). It was discovered by R. H. Sennhauser in 1964 when

the south wall of the choir was breached to accommodate a modern

heating duct. For other discoveries made during these operations, see

preliminary report on Sennhauser's findings (II, 358-59).

Figure 115 shown above is reproduced from an original drawing executed in carbon

pencil, size, 8.5 × 10 inches (215 × 25.5cm). The drawing is based on a document

not adequate for direct photographic reproduction but possessing legibility features

of sufficient clarity and definition of form and detail to permit a drawing to be

developed with reasonable fidelity to the original artifact and satisfactory for the

purpose here.

term "abgeschnürte Vierung."[146] It is true that a great

many Carolingian churches had low transepts, but it is

equally true that high transepts with arch-framed crossing

units existed in St.-Denis, as early as 750-755; in Neustadt-on-the-Main,

shortly after 768/69 (fig. 116); in the Abbey

Church of St. Mary's in Reichenau, before 816 (fig. 117).

The low transept may have been more common, but a

square crossing produced by the interpenetration of two

volumes of space of equal height, and framed by arches on

all four sides, was entirely within the realm of possible

solutions open to a Carolingian architect. Advanced and

superior as he was in so many other respects, the designer

of the Church of the Plan of St. Gall may also, in this

instance, have anticipated a development which had as yet

not found a widespread application in Carolingian architecture.

In our reconstruction of the Church of the Plan (figs.

108-112) we have chosen to emphasize this possibility. Had

we had more leisure and space, we would have supplemented

this solution with an alternate drawing that showed the

Church with a low transept. A reconstruction in which the

Church is furnished with a low transept will be found in

Emil Reisser's study of the Abbey of St. Mary's in

Reichenau-Mittelzell.[147]

The tower of St.-Denis is mentioned in the Miracula Sancti Dyonisi,

I, xv; see Mabillon, Acta, III:2, 348; see also Crosby, 1953, 12-18, and

53, fig. 14.

For Neustadt-on-the-Main, see Boeckelmann, 1951, 43-45; and

idem, 1952, 109; idem, 1956, 58-62.

For St. Mary's at Reichenau, see Reisser, 1933, 163ff; and idem,

1935, 210ff; also Boeckelmann, 1952, 108.

This is the procedure chosen in the case of the Dormitory, the

Refectory, the Cellar, the Abbot's House, and the Stable for Horses and

Oxen; see below, figs. 208, 211, 225, 251; and II, fig. 474.

Seesselberg, 1897, 99, fig. 279; Dehio and von Bezold, I, 1901,

161-62 and Plates, I, pl. 42, fig. 2; Effman, 1899, 163, fig. 134, and 1912,

11, fig. 29; Ostendorf, 1922, 43, fig. 53; Hecht, I, 1928, pl. 4; Gall, 1930,

pl. 1; E. Lehman, 1938, 17, note 2.

Beenken, loc. cit., the discussion of the arch-framed crossing, in

Carolingian architecture suffers somewhat from a skeptical over-reaction

to Effmann's self-assurance in proposing a fully developed arch-framed

crossing in his reconstructions of Centula and Corvey. As far as Centula

is concerned, the situation is not very different from St. Gall. Beenken

could not disprove Effmann's assumption of an arch-framed crossing;

he could only point out that the crossing of Centula need not necessarily

have belonged to the fully developed type suggested by Effmann. On the

problem of the "abgeschnürte Vierung," cf. also Boeckelmann, 1954, 10113;

and Grodecki, 1958, 45ff.

Reisser, 1960, 80ff and figs. 326 and 327. Reisser's reconstruction

of the Church of the Plan (which was made before the publication of the

color facsimile of the Plan in 1952 but published posthumously in 1960)

has two anomalies which I fail to understand. Reisser reduces the arcades

of the nave from 9 to 8; and he omits the transverse arm of the crank-shaped

corridor crypt.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||