The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| II. |

| II. 1. |

| II.1.1. |

| II.1.2. |

| II.1.3. |

| II.1.4. |

| II.1.5. |

| II.1.6. |

| II.1.7. |

| II.1.8. |

| II.1.9. |

| II.1.10. |

| II.1.11. |

| II.1.12. | II.1.12 |

| II.1.13. |

| II. 2. |

| II. 3. |

| III. |

| IV. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

II.1.12

SCRIPTORIUM AND LIBRARY

Nec non sanctorum dicta sacrata patrum;

Hic interserere caveant sua frivola verbis,

Frivola nec propter erret et ipsa manus,

Correctosque sibi quaerant studiose libellos,

Tramite quo recto penna volantis eat.

Per cola distinguant proprios et commata sensus,

Et punctos ponant ordine quosque suo

Ne vel false legat, taceat vel forte repente

Ante pios fratres lector in ecclesia.

Est opus egregium sacros iam scribere libros,

Nec mercede sua scriptor et ipse caret.

Fodere quam vites melius est scribere libros,

Ille suo ventri serviet, iste animae.

Vel nova vel vetera poterit proferre magister

Plurima, quisque legit dicta sacrata patrum.

Together with the inspired Fathers' gloss.

Here let no empty words of writers' own creep in—

Empty, as well, when hand or eye betray.

By might and main they try for wholly perfect texts

With flying pen along the straight-ruled line.

Per cola et commata[75] should make clear the sense

To prevent the lector, before reverend monks in church,

From reading false, or stumblingly, or fast.

Our greatest need these days is copying sacred books;

Hence every scribe will thereby gain his meed.

To copy books is better than to ditch the vines:

The second serves the belly, but the first the mind.

The master—whoe'er transmits the holy Fathers' words—

Needs wealthy stores to bring forth new and old.[76]

On the Scribes by Charles W. Jones.[77]

Alcuin's poem On the Scribes offers a metrical inscription

intended to decorate the entrance of a monastic scriptorium,

perhaps the scriptorium of the Monastery of St. Martin's

at Tours.[78]

95. LUTTRELL PSALTER, LONDON, BRITISH MUSEUM. Add. Ms. 42130, fol. 37

Baptismal scene [by courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum]

97. AACHEN, COLLECTION DR. PETER LUDWIG

Baptismal font, around 1100

96. DEERHURST, GLOUCESTERSHIRE, ENGLAND

Priory church, Saxon baptismal font

LAYOUT

On the northern side of the Church of the Plan, in a

position corresponding exactly to that of the Sacristy and

Vestry, there is a double-storied structure of like design,

which contains "below, the seats for the scribes, and above,

the library" (infra sedes scribentiū, supra bibliotheca). From

a purely functional point of view the location of these two

important cultural facilities is ideal. Their situation at the

northeast corner of the church, in the shadow cast by

transept and choir, protected the scribes from the glare of

the sun as it travelled through the southern and western

portion of its trajectory and allowed them to work in the

more diffused light made available by their east and north

exposure.

The Scriptorium is accessible by a door from the northern

transept arm of the Church. The Library is reached from the

presbytery by a stairway or passage designated the "upper

entrance into the Library above the crypt" (introitus in

bibliothecā sup criptā superius). This implies that there was

another lower entrance, not shown on the Plan, presumably

an internal stair connecting Library and Scriptorium

directly. The Plan depicts the layout of the Scriptorium.

This has in its center a large square table, identical in size

and shape with that for the sacred vessels in the Sacristy

and like the latter, it, too, is raised on a plinth. Along the

north and east walls of the room, there are seven desks for

writing, and seven windows[79]

placed to provide the scribes

with adequate lighting. This, incidentally, is one of the

only two instances where windows are marked on the

Plan.[80]

Unquestionably they owe this distinction to the

fact that they were of vital importance for the work performed

in this room. The windows must have been glazed.

Glass windows, although still a considerable luxury in

Carolingian times, were indispensable in a monastic scriptorium.

That they were actually in use in Carolingian times

is attested in the chronicles of the Abbey of St. Wandrille

(Fontanella) for the period of Abbot Ansegis (823-833) and

by sources pertaining to the cathedral of Reims, for the

time of Bishop Hincmar (845-882).[81]

Also to be mentioned

in this context is a passage in the Casus sancti Galli of

Ekkehard IV, where we are told that Sindolf the Maligner,

while eavesdropping on a conversation carried on in the

scriptorium of St. Gall, pressed his ear at night "to the

glass window where Tutilo was seated" (fenestrae vitreae

cui Tutilo assederat).[82]

The tale, written around 1050, is

almost certainly fictitious, but may in fact reflect the

architectural conditions of the Carolingian scriptorium of

St. Gall, which was rebuilt by Abbot Gozbert, when he

reconstructed the monastery church between 830 and 837.

One observes, not without surprise, that the scriptorium is

not furnished with any facilities for heating.

The other case is the privy of the monks (see below, p. 259) where

windows for light and ventilation are indicated on the east and west wall.

For St. Wandrille see Schlosser, 1896, 289, No. 870 and the more

recent edition of the Gesta Sanctorum Patrum Fontanellensium Coenobii,

ed. Lohier, and Laporte, 1936, 105-106. For the Cathedral of Reims see

Schlosser, op. cit., 250, No. 771.

Ekkeharti (IV.) Casus sancti Galli, chap. 36; ed. Meyer von Knonau,

1877, 133ff; ed. Helbling, 1958, 77ff.

LOCATION

The position of the sacristy "to the right of the apse" (a

dextra absidae) and of the library in a corresponding place

"to the left" (a sinistra eiusdem) is traditional. It existed, as

George H. Forsyth has pointed out, as early as the fifth

century, in the church which St. Paulinus had erected at

Nola near Naples.[83]

Forsyth also drew attention to the

interesting fact that the double-storied side chambers of

the kind found on the Plan of St. Gall were common in

many Early Christian churches of the Near East. The most

striking parallel is to be found in the church of St. John of

Ephesus where this motif is combined with the centralized

Latin-cross plan exactly as in the Church of the Plan of St.

Gall.[84]

ADMINISTRATIVE ORGANIZATION

The Scriptorium and the Library were the intellectual

nerve centers of the monastery. Without the cultural

activities carried on in these spatially relatively modest

facilities, western civilization would not be what it is today.

A substantial portion of what is known to us of classical

learning was transmitted in manuscripts copied in monastic

scriptoria and rescued for posterity in the carefully protected

bookcases (armaria) of monastic libraries (fig. 105).

By the time the Plan of St. Gall was drawn these two

institutions had already developed internally into a fairly

complex organization. Their management was in the hands

of an official who received his orders from the abbot. In

pre-Carolingian times this was, in general, the choirmaster

(cantor) whose leading role in the performance of the daily

choral services made him a natural candidate for this position.[85]

Under the impetus of the Carolingian renaissance,

scriptorium and library were placed in the care of a special

official, the bibliothecarius or armarius (from armarium, the

"press" or "wardrobe" in which the books were kept).[86]

This official became responsible for the maintenance and

administration of an entire system of different collections

of books: the main collection (kept in the central library),

the liturgical collection, i.e., the books used in the divine

services (often chained to their places of use in the church;

otherwise, kept in the Sacristy), and several branch

libraries: viz., a reference library of school books needed

98. AMBO, HAGIA SOFIA AT SALONIKA

ISTANBUL ARCHAEOLOGICAL MUSEUM

[redrawn from Orlandos, 11, 1954, fig. 11]

Novitiate), another one needed for the teaching in the

Outer School (by necessity kept in that location), and a

third collection used for the daily readings of the monks,

the lectio divina established as a primary monastic occupation

by St. Benedict, for which each monk was allowed in

the aggregate some four hours per day.[87]

In St. Gall this position was introduced under Abbot Grimoald

(841-872). The first known holder of the title is Liuthard (858-886) who

refers to himself as diaconus et bibliothecarius or monachus et bibliothecarius.

He is followed by such men as Uto, Notker, Balbulus, and

Waldram (end of ninth and turn from the ninth to the tenth century).

See Bruckner, 1938, 33 and Roover, 1939, 615.

READING COLLECTION

The reading collection was of substantial size and must

have been composed of at least as many books as there were

monks in the monastery, since the Rule prescribes that

each monk be handed a book at the beginning of Lent

which as the year went by he was bound "to read it in

consecutive order from cover to cover."[88]

The selection

and distribution of this material was one of the duties of the

provost. A directive issued at the synod of 816 allowed him

to augment the regular annual allotment at his discretion.[89]

The titles of the books loaned out in this manner were

entered in a check-out list (breve) to facilitate their return

and assure control over the holdings.[90]

Hildemar, in his

commentary to the Rule, written around 845, provides a

detailed, here abridged, description of this procedure:

The librarian (bibliothecarius) with the aid of the brothers

takes all the books to the chapter meeting. There they

spread out a rug, upon which the books are placed. After

the regular business of the chapter meeting has been concluded

the librarian announces from the check-out list

(breve) the titles of the books and the names of the monks

to whom they had been lent in the preceding year. Thereupon

each brother deposits his book on the rug. Then the

provost, or anyone else to whom he may have delegated this

task, collects each book, and as it is being returned, he

probes the brother with questions whether he has diligently

studied his assignment. If the response is satisfactory, he

inquires of the brother which book he considers to be of

use to him in the coming year and provides him with the

desired book. However, if the abbot finds that a book is not

suited for a brother who asked for it, he does not give it to

him but hands him a more suitable one. If the interview

establishes that the brother was derelict in his study, he is

not given a new book, but asked to study the old one for

another year. If the abbot finds that the brother has studied

with diligence, but is nevertheless not capable of comprehending

it, he gives him another one. After the brothers

have left the chapter meeting, the abbot sees to it that all

books that have been entered in the check-out list are

accounted for, and if they are not on record, searches until

they are found.[91]

The books disposed of in this manner were obviously

not kept in the central library, but were in permanent

circulation, each monk retaining his own copy, which he

probably kept on a shelf or locker under or near his bed,

together with the other modest supplies that the Rule

allowed him.[92]

Benedicti regula, chap. 48, ed. Hanslik, 1960, 114-19; ed. McCann,

1963, 110-13; ed. Steidle, 1952, 246-51: "In quibus diebus Quadragesimae

accipiant omnes singulos codices de bibliotheca, quos per ordinem ex integro

legant; qui codices in capite Quadragesimae dandi sunt."

Synodi primae decr. auth., chap. 18, ed. Semmler in Corp. Cons.

Mon., I, 1963, 461: "Ut in Quadragesima libris de bibliotheca secundum

prioris dispositionem acceptis, aliis nisi prior decreuerit expedire non accipiant."

MAIN LIBRARY

In his Renaissance of the Twelfth Century Charles Homer

Haskins made the remark that "when men spoke of a

library in the Middle Ages they did not mean a special

room, and still less a special building" but rather thought

of a "book press" or wardrobe, as is suggested by the word

armarium commonly used for libraries.[93]

I do not know

whether this assessment is tenable for the later Middle

Ages. It is certainly not what the framers of the Plan of St.

Gall had in mind for a monastic library of the time of

Charlemagne or Louis the Pious. The Plan provides for a

central library of a surface area of 1600 square feet, located

over a scriptorium of identical dimensions, the two together

totaling 3200 square feet. We know at least of one

other Carolingian library that was installed in a separate

building: that of the monastery of St. Wandrille (Fontanella).

It stood in the cloister yard in front of the Refectory,

and opposite it, on the other side of the yard, was a

twin building which served as charter house.[94]

In the

monastery of St. Emmeran there must have been a special

library, for it is said of Bishop Wolfgang (972-94) that he

had it decorated with metrical inscriptions of his own composing.[95]

If Haskins infers from Lanfranc's description of

the annual distribution of the daily reading matter that "all

of the books of a monastery can be piled on a single rug"

this cannot be taken as referring to the whole of the

monastic library, but only to that portion of it that was

checked out to the monks at the beginning of Lent.[96]

In

such monasteries as St. Riquier and Corbie, which housed

as many as 350 to 400 monks, even this circulating portion

of the general library holdings must have been of substantial

bulk.

Library and Charter House are listed in the Gesta Sanctorum Patrum

Fontanellensis Coenobii amongst the buildings erected by Abbot Ansegis

(822-833): "In medio autem porticus, quae ante dormitorium sita uidetur,

domum cartarum constituit. Domum uero qua librorum copia conseruaretur

quae Graece pyrigiscos dicitur ante refectorium collocauit" (Gesta Sanctorum

Patrum., ed. Lohier and Laporte, 1936, 107). The text says nothing

about the size of this building, but the cloister yard in which it stood

must have been of spectacular dimensions, since the Dormitory and the

Refectory, which formed two sides of the square, as is stated elsewhere

in the same text, were each 208 feet long.

For a visual reconstruction of the layout of the Carolingian monastery

of St. Wandrille, see W. Horn, "The Architecture of the Abbey of

Fontanella, From the Time of its Foundation by St. Wandrille (A.D. 649)

to the Rebuilding of its Cloister by Abbot Ansegis (823-833)," Speculum

(in press).

Haskins, loc. cit. Lanfranc's description of the distribution of books

at Lent, is a slightly shortened version of Hildemar's account of ca. 845.

It is given in the chapter Feria Secunda Post Dominicam Primam Quadragesimae.

See Decreta Lanfranci, ed. and trans. by David Knowles, 1951,

19ff and Decreta Lanfranci, ed. Knowles, 1967, 19-20.

WRITING POSTURE AND VARIOUS

CLASSES OF SCRIBES

All of these books were written by the monks themselves

in the scriptorium. The scriptorium served not only as

work room for copying scribes, it was also the monastery's

chancellery, where letters, deeds, and documents were

written. The scribes sat upon stools before tables or desks,

the writing surface of which rose at a sharp angle so that

the scribe wrote almost in a vertical plane. The book from

which a new text was copied was held in a firm position by

a reading frame. This is a posture quite distinct from that

which was in use in ancient times, when the scribes wrote

either standing (as seems to have been the rule in court

procedure) or seated held their writing materials in their

lap, as is shown in the illumination of prophet Ezra, on fol.

5r of the famous Codex Amiatinus (fig. 105), that was

copied, early in the eighth century, in the monastery of

Jarrow and Monkwearmouth in Northumbria from an

illustration of the same subject in the sixth century manuscript

of the Institutiones of Cassiodorus. The transition

from this ancient custom of holding on one's lap the scroll or

codex on which one was writing to the medieval custom of

writing on a desk (fig. 106) was made in the course of the

eighth century, as a recent study has disclosed. It has two

probable causes: for one the growing popularity of large

deluxe codices, which it was well nigh impossible to cover

with writing without the use of some firm support to steady

the hand of the scribe, and second, the fact that the craft of

writing (in ancient times essentially in the hands of slaves),

in the monastic scriptoria in the north had become the

prerogative of an intellectual elite, whose high social

standing called both for greater comfort and greater efficiency.[97]

Medieval sources in referring to scribes distinguish

between antiquarii, the experienced writers whose skills

were reserved for the making of liturgical books; scriptores,

the less trained but still reliable writers; rubricatores,

writers who specialized in the insertion of decorative letters

rendered in different colors, usually in connection with

opening words; miniatores, the highly skilled scribes who

embellished the manuscript with its pictorial illuminations;

and last, but not least, the correctores, the proof

99. PLAN OF ST. GALL. TRANSEPT, PRESBYTERY, EASTERN APSE AND PARADISE

From the crossing two flights of stairs, each of seven steps, lead to the Presbytery, leaving between them a passage to the CONFESSIO where monks

can pray in privacy near the tomb of St. Gall. Presbytery and Crypt are one of two places on the Plan where different levels are shown in the

same plane: above, the high altar dedicated to SS Mary and Gall; and below, a u-shaped corridor leading laymen to the tomb of St. Gall. In the

two-storied spaces located between Presbytery and transept arms the draftsman delineates the plan of just one level. He identifies another level only

by an inscription—his standard method of indicating a superincumbent level.

most learned monks. The manuscripts of the Abbey of St.

Gall as well as those of many other writing schools abound

with marginal or interlinear annotations that testify to the

care with which this work was done.[98] At Reichenau this

task was performed by Reginbert (d. 847), librarian under

four successive abbots—that same Reginbert who seems to

have supervised the writing of the explanatory titles of the

Plan of St. Gall.[99] At St. Gall this work was done by such

famous teachers as Ratpert, Notker, and Tutilo. Purity and

correctness of the sacred texts was a primary concern of the

period (as Alcuin's poem attests) and of sufficient interest

even to the emperor to be singled out as a matter of

statewide importance in a capitulary issued in 789, or 805,

in which it is stipulated that the copying of such sacred

texts as the Gospels, the Psalter, and the Missal should

only be entrusted to men of superior intellectual attainment

(et si opus est evangelium, psalterium et missale scribere,

perfectae aetatis homines scribant cum omni diligentia).[100]

On the introduction of writing desks, their sporadic appearance in

Early Christian times, their general acceptance in the age of Charlemagne

and the occasional retention of earlier forms, see the interesting

chapter, "When did scribes begin to use writing desks?" in Metzger,

1968, 123-37.

On corrections and emendations in the manuscripts of the Abbey of

St. Gall see Bruckner, 1938, 29ff. On the various types of scribes see

Roover, 1939, 598ff.

Admonitio generalis, 23 March 789, chap. 72; ed. Boretius, in Mon.

Germ. Hist., Leg. II, Capit., I, Hannover, 1883, 60.

METHOD OF CATALOGING AND SHELVING BOOKS

Once a manuscript was written and corrected, its title

was entered in the catalogue that listed the monastery's

holdings in books—not in alphabetical sequence, but

according to subject matter, and probably in the same

order in which the books were shelved in their wooden

cases.[101]

A splendid example of this kind of furniture is

shown in the illumination of Prophet Ezra on fol. 5R of the

famous Codex Amiatinus (fig. 105).[102]

Another one of

practically identical design is depicted on the mosaic of St.

Lawrence in the mausoleum of Galla Placidia (424-450).[103]

The books, as these works disclose, lay on their sides, and

did not stand. This is confirmed by the fact that their titles

are, in general, entered lengthwise, not crosswise, on the

back of the book.[104]

To judge by the number of volumes

listed in extant monastic catalogues, Carolingian libraries

must have been equipped with a considerable number of

such wooden "wardrobes" for the shelving of books. A

catalogue compiled by Reginbert of Reichenau enumerates

415 manuscripts.[105]

The holdings of the library of St. Gall,

according to a catalogue compiled at the time of Abbot

Grimald (841-872), lists 400 volumes.[106]

Grimald himself

had a private collection of 34 volumes that after his death

went to the general library.[107]

His follower, Hartmut (872883)

collected for himself another 28 volumes. These, too,

were bequeathed to the general library on his death.[108]

The longest title list found for any Carolingian monastery

appears to be the list of the library of the monastery of

Lorsch. It amounted to 590 titles.[109]

NUMBER OF SCRIBES & COLLABORATION

The number of monks who sat at work in the scriptorium

must have varied greatly. The layout of the Scriptorium on

the Plan of St. Gall would allow fourteen monks to write

simultaneously, if we assume that each writing desk was

manned by two scribes. Since there are ten feet of space

between each window, two scribes could have worked in

comfort at a single desk. But the total number of scribes at

work each day in the Scriptorium could have been considerably

increased if the scribes worked in shifts.

A. Bruckner, on the basis of an actual count of the hands

at work in individual manuscripts, has calculated that the

monastery of St. Gall, between 750 and 770, employed

some twenty-five scribes for copying manuscripts and

around fifteen more for writing documents—a total of

forty.[110]

Under Abbot Waldo and shortly after him (770790)

the number of scribes rose to about eighty;[111]

under

Abbot Gozbert (816-836) to about a hundred.[112]

Some of

these may have worked in carrels, in one of the cloister

walks, as was customary in Tournai in the eleventh

century[113]

and to be found later on in many other places.[114]

A codex was rarely written entirely by a single hand. At

the scriptorium of St. Martin's at Tours, in the first half of

the eighth century, more than twenty scribes collaborated

in a copy of Eugippius.[115]

The texts of other manuscripts

copied at that same school were written, variously, by five,

seven, eight, or twelve different hands.[116]

Fourteen scribes

listed by name in manuscripts of St. Martin appear in a

register drawn up in 820.[117]

ROMANESQUE CHURCH BENCH, MONASTERY OF ALPIRSBACH

100.

100.X

FORMERLY STUTTGART, SCHLOSSMUSEUM

(DESTROYED IN WW II.) After Falke, 1924, pl. 1

Although probably not antedating the thirteenth century, this medieval church bench with its simple carpentry embodies a type one

would expect to have been in use centuries earlier. The drafter of the Plan referred to this type of bench as FORMULA (see above

p. 137 and Glossary, III, s.v.). Four such benches, each with a seating capacity of not more than four people, would have been

set up in the crossing of the Church probably for use by a specially trained choir singing in antiphon.

HEXHAM, NORTHUMBERLAND, ENGLAND

NIGHT STAIRS, PRIORY CHURCH

Unquestionably one of the finest extant medieval night stairs, located in the southern transept arm, it leads directly from dormitory into church.

In general such stairs provided the only connection between dormitory and cloister. In the 12th and 13th centuries, they were invariably made of

stone; in earlier times perhaps of timber. Except for those in the Church, the author of the Plan of St. Gall omits stairs from it.

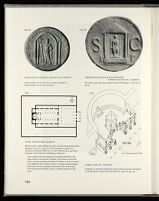

102.A GOD JANUS UNDER A CELESTIAL CANOPY

Roman medal of A.D. 187, more than twice original size

[after Gnecchi, II, 1912, pl. 84, fig. 5]

104. TYRE, PALESTINE (LEBANON)

Basilica built by Bishop Paulinus in A.D. 314. Reconstructed plan [after

Nussbaum, 1965, II, 24, fig. 1]. The reconstruction is based on a

description by Eusebius, History of the Church (X, 4, 44) where

the layout of Synthronon and Bema is referred to:

"after completing the great building he [Constantine] furnished it with

thrones high up, to accord with the dignity of the prelates, and also with

benches arranged conveniently throughout. In addition to all this, he placed

in the middle the Holy of Holies—the altar—excluding the general public

from this part too by surrounding it with wooden trellis-work wrought

by the craftsmen with exquisite artistry, a marvellous sight for all who

see it."

102.B EMPEROR DOMITIAN ENTHRONED

UNDER CELESTIAL CANOPY

Sestertius, nearly three times original size [after Mattingly, II, 1930, pl. 77,

fig. 9]

103. ROME. OLD ST. PETER'S

Presbytery, as rebuilt by Gregory the Great between 594-604. Drawing by

S. Rizzello [after Toynbee and Ward-Perkins, 1956, 215, fig. 22]

Bruckner, 1938, 17. Under Abbot Sturmi (744-779) the same

number, i.e., forty scribes, were constantly employed in the scriptorium

of Fulda. See Thompson, 1939, 51.

Of Tournai it is written "if you had gone into the cloister you

might in general have seen a dozen young monks sitting on chairs in

perfect silence, writing at tables, carefully and skillfully constructed (ita

ut si claustrum ingredereris, videres plerumque duo decim monachos juvenes

sedentes in cathedris et super tabulas diligenter et artificiose compositas cum

silentio scribentes)." See Wattenbach, 1896, 271-72. Whether claustrum

in the passage quoted above can be interpreted as "cloister walk" rather

than "claustral range of buildings" is subject to question: and this

matter as well as the evidence cited by Roover in support of the assumption

that in certain cloisters certain scribes performed their craft in the

open cloister walk (Note 104) requires careful re-examination.

DAILY WORK SPAN

The daily work span of a medieval scribe, to judge by an

anonymous writer of the tenth century, was six hours.[118]

In Cluny, in the twelfth century, the scribes were exempted

from certain choir prayers;[119]

but in the ninth century,

according to Hildemar, a scribe was not allowed to complete

a verse "once the bell for the divine service was rung,

not even a letter which he had started, but must instantly

set it aside unfinished."[120]

The same author lists as the

indispensable tools of the scribe: the pen (penna), the quill

(calamus), the stool (scamellum), the scraping knife (rasorium),

the pumice stone (pumex), and the parchment

(pergamena).[121]

In general, writing was a daytime activity but occasionally

we hear of a monk being at this task before or after

sunset, as in a marginal annotation to a ninth century copy

of a text by Cassidorus, made in a monastery at Laon,

which reads: "It is cold today. Naturally, Winter. The

lamp gives bad light."[122]

From Ekkehart IV we learn that

Ratpert, Notker, and Tutilo had permission from the abbot

to convene at night in the scriptorium for collating and

correcting texts.[123]

But there were also those more joyous occasions in the

spring or early summer when a monk would do his writing

outdoors under the shade of a tree, as evidenced in a

charming marginal gloss of an Irish manuscript of an

eighth- or ninth-century Priscian in the Library of St. Gall

(ms. 904), which reads:

A blackbird's lay sings to me

Above my lined booklet

The trilling birds chant to me

The cuckoo sings

Verily—may the Lord shield me!

Well do I write under the greenwood.[124]

"Arduous above all arts is that of the scribe: the work is difficult

and it is also hard to bend necks and make furrow on parchments for six

hours" (Madan, 1927, 42; Roover, 1939, 605).

"Scriptor non debet pro verso complendo stare aut certe pro litera

perficienda . . . sed statim imperfecta debet dimittere, sicuti illa sonus signi

invenerit" (Expositio Hildemari; ed. Mittermüller, 1880, 458-59). The

scribe's stopping in the middle of a letter, on the sound of the bell—as

Charles W. Jones informs me—duplicates the act of brother Marcus of

Scete in Pelagius' Verba Seniorum, XIV (Vitae Patrum, V). Transl.

Helen Waddel, The Desert Fathers, London, 1936, 163.

The stipulation appears in almost identical form in the Institutiones of

Cassian and in a slightly different wording in the Regula magistri (for

quotations and reference to sources see Nordenfalk, 1970, 99)."

"Erat tribus illis inseparabilibus consuetudo, permisso quidem prioris,

in intervallo laudum nocturno convenire in scriptorio colationesque tali

horae aptissimas de scripturis facere" (Ekkeharti (IV.) Casus sancti Galli,

chap. 36; ed. Meyer von Knonau, 1877, 133-34; ed. Helbling, 1958,

77-78).

An Anthology of Irish Literature, edited with an Introduction by David H. Greene, New York, 1954, p. 10, after a translation by Kuno Meyer. For the Old Irish version, see Thesaurus Paleohibernicus, A Collection of Old-Irish Glosses, Scholin Prose and Verse, edited by Whitley Stokes and John Strachan, vol. II, Cambridge, 1903, 290. The gloss was brought to my attention by Wendy Stein.

A NOBLE OR BACKBREAKING TASK?

The work in the scriptorium was conducted in silence

and during the hours assigned for that purpose no monk

could leave the scriptorium without permission of the

abbot. Apart from the scribes themselves, only the abbot,

the prior, the subprior, and the librarian had access to the

scriptorium.[125]

The writing of sacred texts was held in high

esteem and in general considered a more noble task than

such physical labors as working in the fields. This is expressed

in unmistakable terms in Alcuin's poem about the

scribes.[126]

In Ireland where the art of calligraphy had risen

to unprecedented heights the life of a scribe was held in

such high regard that the penalty for killing a scribe was

made as great as that for killing a bishop or abbot.[127]

Yet there is no dearth of evidence that, Alcuin notwithstanding,

writing was also bemoaned as an arduous physical

task, as witnessed by such marginal annotations as:

O quam gravis est scriptura: oculos gravat, renes frangit.

simul et omnia membra contristat. Tria digita scribunt,

totus corpus laborat.[128]

Writing is excessive drudgery. It crooks your back, dims

your sight, twists your stomach and your sides. Three

fingers write, but the whole body labors.

From a Visigothic legal manuscript of the eighth century, Mon.

Germ. Hist., Legum, III, 589. Cf. Wattenbach, 1896, 283 and Roover,

1939, 607. For other touching exclamations on the strains of writing,

see Wattenbach, loc. cit. and Lindsay, loc. cit.

"Per cola et commata (by clauses and phrases)," a standard locution in every scriptorium, described St. Jerome's practice of dividing scriptural prose into rhetorical verses as assistance to a public reader: "But just as we are accustomed to copy Demosthenes and Cicero by clauses and phrases, even though they are composed in prose, not verse, so we, looking to the convenience of readers, have broken up our new translation by writing it in a new fashion." (St. Jerome, Preface to Isaiah, Patrologia Latina XXVIII, 771B; cf. 938-39. Consult Evaristo Arns, La technique du livre d'après St. Jérôme, Paris, 1953, pp. 114-15.)

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||