The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| II. |

| II. 1. |

| II.1.1. |

| II.1.2. |

| II.1.3. |

| II.1.4. |

| II.1.5. |

| II.1.6. |

| II.1.7. |

| II.1.8. | II.1.8 |

| II.1.9. |

| II.1.10. |

| II.1.11. |

| II.1.12. |

| II.1.13. |

| II. 2. |

| II. 3. |

| III. |

| IV. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

II.1.8

PRESBYTERY

HIGH ALTAR: ST. MARY AND ST. GALL

Raised as it is by seven steps above the level of the transept,

the presbytery with its high altar dominates the entire

Church. The liturgical pre-eminence of this part of the

building is emphasized by a hexameter in capitalis rustica:

SC̄A SUPER CRPTĀ SC̄ŌRUM

STRUCTA NITEBUNT

ABOVE THE CRYPT THE

HOLY STRUCTURES OF THE SAINTS

SHALL SHINE.

The "holy structures" are the high altar of the Church,

dedicated jointly to St. Mary and St. Gall (altare sc̄ē mariae &

scī galli) and the tomb of the holy body (sacrophagū scī

89. MEROVINGIAN CARVED STONE

POITIERS, MUSÉE DU BAPTISTÈRE, FRANCE

[photo: Photomecaniques]

The stone may have come from the

church of Notre-Dame l'Ancienne.

90. MARBLE SLAB WITH CROSS

& SIX-LOBED ROSETTES (8TH CENT.)

LUCCA, MUSED DI VILLA GRININI

Associated with the cross, as in many

Syrian, North African and Visigothic slabs

of earlier periods, the six-lobed rosette

probably retained its original meaning as a

symbol of light overcoming evil forces allied

with darkness. In the Middle Ages the

symbol went underground.

[after Arte Lombarda, suppl. vol. 9:1]

92. HEX SIGNS

On Pennsylvania Dutch barns, they often are several feet in diameter

[after Sloane, 1954, 67]

91. SIX-LOBED ROSETTE IN MASONRY OF

MONASTIC BARN (1211-1227) PARCAY-MESLAY, FRANCE

[photo: Horn]

The rosette was cut into masonry or timber work of many medieval

tithe barns as a spell to ward off harm to livestock or harvest.

the altar.

The joint patrocinium of Mary and St. Gall has its

explanation in the fact that Mary was the patron of the

original oratory of St. Gall. The deeds of the Monastery

disclose how in the course of the eighth century the name

of St. Gall began to be associated with that of Mary with

increasing frequency until it eventually replaced it entirely

and became the local place name (coenobium sancti Galli, or

sancti Galloni).[56]

The altar is raised on a plinth, a distinction

not accorded any other altars in the Church. We must

expect it to have been surmounted by a canopy. A capitulary

issued by Charlemagne in 789 directs that altars should

be surmounted by such superstructures (Ut super altaria

teguria fiant vel laquearia).[57]

An ancient symbol of the

celestial dome and hence, by implication, of universal

rulership, this motif had been transmitted from the Roman

rank of the gods (fig. 102.B),[60] and from the emperor to Christ

as Christ acquired the status of a Roman state god. It was

no lesser person than Constantine the Great who set a

conspicuous precedent for this transmission of celestial

prerogatives to the new God of Heaven when he adorned the

high altar of the latter's prime apostle with a pedimented

canopy richly revetted with silver and gold, in the Church

of St. Peter's in Rome (fig. 104).[61]

Duplex legationis edictum, May 23, 789, chap. 33; ed. Boretius,

Mon. Germ. Hist., Leg. II, Cap., I, 1883, 64. Considering the vast

number of altars with which churches were equipped during this period,

it is possible that the law applied only to the high altar.

WALL BENCHES

Wall benches lined both sides of the fore choir and

continued into the round of the apse. The monks faced

each other vultus contra vultum from either side of the

altar, except for those who sat in the curving parts of the

apse, and faced the altar westward. The abbot presumably

sat at the apex of the apse and had a counterpart in the

choir master, who occupied a position of comparable

centrality in the middle of the crossing square. The layout

of the benches discloses that crossing and presbytery—

despite their different levels—formed liturgically a unitary

space; and a count of the sitting places available for the

monks in the areas screened off for their exclusive use in the

eastern parts of the Church suggests that when the entire

community participated at a common service, even the

benches in the transept arms were occupied by monks

attending the service,[62]

. On the north side "an upper

entrance leads into the library above the crypt" (introitus

in bibliothecā sup criptā superius). The qualifying adjective

"upper" implies the existence of a "lower" entrance, which

must have made the library accessible from the Scriptorium

below it. The prototype for the raised platform of the

presbytery and the apse of the Church of the Plan of St. Gall

was the raised presbytery that Pope Gregory the Great had

installed in Old St. Peter's in Rome between 594 and 604

(fig. 104) by lifting the pavement of the new choir 5 feet

above the original floor of the church and establishing

below this platform a crypt that incorporated directly

beneath the new altar the old shrine of St. Peter, which

before this alteration had been exposed to view.[63]

TOMB OF ST. GALL AND ITS RELATION

TO THE CRYPT

There has been considerable discussion on whether the

tomb of St. Gall should be interpreted as standing in the

presbytery above, or in the crypt below it; and whether, if in

the crypt, it should be thought of as standing behind or

underneath the altar.[64]

It should be remarked that on the

Plan the tomb is entered on the east side of the altar, and

that the plurality of "holy structures" referred to in the

affixed hexameter as "shining above the crypt" should

lead one to think that the sarcophagus stood in the upper

sanctuary.

Despite these facts, it has generally been assumed that

the tomb of St. Gall was meant to stand in the crypt underneath

the presbytery, and for good reason, since it was the

desire to find appropriate protection for the relics, in the

first place, that had led to the invention of crypts. The

proper solution to this puzzle may have been found by

Willis when he speculated, "It is not impossible that

although the real sepulchre of the saint was in the confessionary

or crypt below, a monument to his honour may

have been erected above the altar."[65]

That such a double-storied

structure actually existed in St. Gall is suggested by

two tales reported in the Miracles of St. Gall. One of these

tales speaks of a cripple who was taken by his friends to the

memoriam B. Galli and daily "laid close to the sepulcher in

the crypt" (cottidie juxta sepulchrum in crypta collocatus).

Another tale mentions "a lamp which burned nightly

before the upper altar and tomb and which also threw some

light through a small window upon the altar of the crypt"

(lumen quod ante superius altare et tumbam ardebat per

quandam fenestrum radios suos ad altare infra cryptam

positum dirigebat).[66]

Some further information concerning

the topographical relation of tomb and altar at St. Gall can

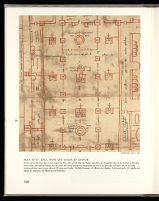

93. PLAN OF ST. GALL. NAVE AND AISLES OF CHURCH

In the axis of the nave, west to east: baptismal font, altar of SS John the Baptist and John the Evangelist, altar of the Saviour at the Holy

Cross, ambo; and midway between the two latter, two crucial inscriptions designating the nave as 40 feet wide, and each aisle, 20 feet wide.

In the north aisle, west to east: altars of SS Lucia and Cecilia, The Holy Innocents, SS Martin and Stephen. In the south aisle: SS Agatha and

Agnes, St. Sebastian, SS Mauritius and Lawrence.

work informs us that on his death at Arbon, October 16,

about the year 646, the body of the Saint was taken to his

oratory at St. Gall and buried in a grave dug between the

altar and the wall.[67] Forty years later, his sepulcher was

violated by plunderers who mistook the coffin for a treasure

chest, but Boso, Bishop of Constance, replaced the coffin

"housing the relics of the sacred body, in a worthy sarcophagus

between the altar and the wall, erecting over it a

memorial structure congruent with the merits of the God-chosen."[68]

The chronicles of St. Gall report no further

translation of the Saint, and from this fact, as Willis concluded

correctly, it has to be inferred that the location of

the tomb remained the same, even in Gozbert's church.[69]

Nowhere in any contemporary allusions to the sepulcher of

the Saint, is the tomb reported to stand underneath the altar.

For the latest discussion, see Reinhardt, 1952, 20, where the tomb is

reconstructed standing directly beneath the altar.

Willis, loc. cit. The Life and Miracles of St. Gall was written by an

anonymous monk of St. Gall during the last third of the eighth century.

At the request of Abbot Gozbert (816-837) this work was re-edited in

833-34 by Walahfrid Strabo, who incorporated into his edition a continuation

of the account of the miracles which had been written by the

Monk Gozbertus, a nephew of Abbot Gozbert. Best edition: Vita Galli

confessoris triplex, ed. Bruno Krusch, Mon. Germ. Hist., Script. rer.

merov., IV, Hannover, 1902, 229-337. The miracles to which Willis

refers belong to the part that was written by the Monk Gozbertus. See

"Vita Galli auctore Walahfrido," Liber II, chaps. 31 and 24, ed. Krusch,

1902, 331 and 328-29.

"Sepulchrum deinceps inter aram et parietem peractum est, ac melodiis

caelestibus resonantibus corpus terrae conditum." See "Vita Galli auctore

Wettino," Liber II, chap. 32, ed. Krusch, 1902, 275.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||