The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| II. |

| II. 1. |

| II.1.1. |

| II.1.2. |

| II.1.3. |

BELL TOWERS OR TOWERS OF DEFENSE

AND SURVEILLANCE? |

| II.1.4. |

| II.1.5. |

| II.1.6. |

| II.1.7. |

| II.1.8. |

| II.1.9. |

| II.1.10. |

| II.1.11. |

| II.1.12. |

| II.1.13. |

| II. 2. |

| II. 3. |

| III. |

| IV. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

BELL TOWERS OR TOWERS OF DEFENSE

AND SURVEILLANCE?

It cannot be stressed with sufficient strength that the

explanatory titles associated with these towers fail to make

any reference to campana, signa, or tintinnabula; and for

that reason they cannot be interpreted as bell towers. On

purely historical grounds this would be a perfectly feasible

assumption. Bells set in motion with ropes, to mark the

various phases of the divine services or other festive events,

are mentioned at various places in the History of the

Franks of Gregory of Tours (d. 593/94). In the course of

the seventh and eighth centuries the evidence in contemporary

sources attesting their existence increases so

markedly that it can safely be assumed that they existed elsewhere.[12]

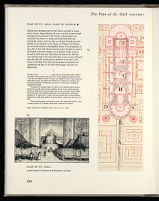

82. PLAN OF ST. GALL. PLAN OF CHURCH

Shaded areas distinguish parts of the Church accessible to monks,

and to laymen. Approaching by the access road (A) cutting through

the large service yard west of the Church, visiting pilgrims are

received by the Porter in a square porch (B) lying before the

semicircular atrium, and from there are directed through two more

porches (C, D), the poor to the Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers,

the rich to the House for Distinguished Guests. Two passageways no

more than 7½ feet wide channel entering laymen through the aisles of

the Church, across the transept, to a U-shaped corridor crypt at

the end of which they may kneel before the tomb of St. Gall (E).

Two reserved areas in the nave allow them to hear sermons delivered

from the ambo (F), attend services celebrated at the altar of the

Savior at the Holy Cross (G), and participate in baptismal rites

conducted at the altar of SS John the Evangelist and John the

Baptist (H).

The pale red tint defines the area of the church proper. This, in

its totality was the province of the monk. Part of it he willingly shared with laymen

so that they also might be touched by mystery and deepened in faith. Those areas of the

church where layman and pilgrim were welcome and to which their movements were

restricted for enjoyment, contemplation, and prayer are indicated in a meandering

vignetted black stipple:

The pattern of circulation began at the Entry Porch, flowed along the aisles of

the church, passed by shrines and nave columns all with carved capitals supporting

arcades and walls above the arcades aglow with the color of painting. Then reaching

the crossing square, the circulation descended by stairs beneath apse and high altar

(dedicated to St. Mary and St. Gall) to the crypt passage where at point of climax,

illuminated by candle light, immersed in vibrant shadow, could be seen the tomb of St.

Gall.

This was moving theater and impressive, even to the sophisticated viewer. In such

a setting the Order of St. Benedict would gather momentum for centuries.

SCALE OF PLAN: 3/10 ORIGINAL SIZE (1:192 × 0.3 = 1:640)

83. PLAN OF ST. GALL

ACCESS ROAD TO CHURCH & MONASTERY GROUNDS

the towers of the Plan of St. Gall do not contain any suggestion

that they were meant to house bells; and there is

some doubt in my mind that any bells suspended in these

towers could have successfully fulfilled their function. The

use of these instruments implies an element of timing

which requires that the brother charged with the task of

ringing them be within sight or hearing of the officiating

priest.[13] Bell ringers stationed in the isolated towers of the

Church of the Plan of St. Gall could have neither seen nor

heard the priest.[14]

For Tours see Otte, 1884, 9 and Mon. Germ. Hist., Script. Rer.

Merov., I:1, 1885, 258; for the seventh and eighth century sources see

Otte, op. cit., 12ff and von Sommerfeld, 1906, 198ff.

The monastic consuetudines of the period abound with references

to bells and tell us exactly at what point in the divine service they were

struck. Bells of "small," "middling," and "large" size (signum pussillum,

signum modicum, signum majus) are mentioned in the Consuetudines

Cluniacenses antiquores, which reflected a considerably earlier tradition

with which Benedict of Aniane was familiar. See Cons. mon., ed. Bruno

Albers, II, 1905, 2 and 3. For other references to bells, see under the

words campana, signum, tintinnabulum, cymbalum in the indices of Corp.

cons. mon., 1963; Schlosser, 1896; and Cons. mon., I-V, 1900-12; as well

as in Du Cange's Glossarium.

A rectangular bell of Irish design and probably Irish provenience is on

exhibit in the Stiftsbibliothek of St. Gall. It was used, according to tradition,

by St. Columban and St. Gall in a cell which these two missionaries

occupied from 610 to 612 in the vicinity of Bregenz (Gallenstein). The bell

is of sheet iron. It is 33 cm. high, has a diameter at the bottom of 15 cm. ×

23 cm. and at the top of 11 cm. × 17 cm. It was never suspended in a

bell tower, but apparently held in the hand and struck on one of its outer

surfaces with the aid of a club or rod. Before the introduction of cast

bronze bells, hammered iron bells of this type were used not only in

Ireland, but also on the Continent. Walahfrid Strabo tells us that they

were called "signals" (signa) and used to announce the hours of the

divine service (quibusdam pulsibus significantur horae). The "St. Gall-Bell

of Bregenz" is dealt with by Duft, 1966, 425-36, where, incidentally,

attention is drawn to the fact that the squarish design of modern Alpine

cow bells is derived from that of the service bells used in the early Irish

monasteries of the Alpine forelands. The spread of the form has an

interesting etymological parallel in the propagation of the word with

which this object is designated: the German word Glocke comes from

Irish clogg through the intermediary stages of Medieval Latin clocca and

Old High German glokka (Duft, op. cit., 431).

From a strictly practical point of view, a small towerlike superstructure

over the transept would have provided a more suitable solution

for placing bells to announce the various phases of the liturgical cycle

than two isolated towers standing at a distance of over 300 feet from the

high altar. In large metropolitan churches, as well as in smaller parish

churches which were designed primarily for the worship of laymen,

conditions may have been different.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||