The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| II. |

| II. 1. |

| II.1.1. |

| II.1.2. |

| II.1.3. | II.1.3 |

| II.1.4. |

| II.1.5. |

| II.1.6. |

| II.1.7. |

| II.1.8. |

| II.1.9. |

| II.1.10. |

| II.1.11. |

| II.1.12. |

| II.1.13. |

| II. 2. |

| II. 3. |

| III. |

| IV. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

II.1.3

TOWERS

Two doors in the outer atrium wall, placed midway

between the outer porch and the two inner porches give

access to two detached circular towers. Their diameter is

30 feet and their closest point lies at a distance of 7½ feet

from the outer atrium wall. Both towers are ascended by

winding stairs, suggested graphically by spirals and verbally

by an inscription in the northern tower (from the hand

of the main scribe) which reads: "Ascent by a spiral

staircase to survey the entire orbit [of the monastery] from

above" (ascensus per c·/·ocleam ad uniuersa super inspicienda).

A title in the southern tower (written by the same hand)

simply states: "another one of the same kind" (alter

similis). The northern tower has in its summit an altar

dedicated to the archangel Michael (in summitate altare sci

Michahelis archangeli), the southern tower, an altar dedicated

to archangel Gabriel (in fastigio altare sci Gabrihelis

archangeli). These last two titles are written by the hand

of the second scribe in such a pale shade of ink that they

are barely legible.[6]

CONNECTION WITH IRELAND?

The purpose of the two detached towers of the Plan of

St. Gall has been the subject of a considerable amount of

controversy. J. R. Rahn suggested a connection with the

round towers of Ireland (fig. 85).[7]

But it appears that no

circular towers are known to have existed in Ireland early

enough to have been copied on the Plan of St. Gall.[8]

Moreover,

there is nothing else in the architectural layout of the

Plan that would suggest any special ties with Ireland; and

the general trend of the monastic reform movement, to

which the Plan owes its existence, was away from the Irish

tradition rather than toward it.

CALL TOWERS OR FUNERARY LIGHT TOWERS?

Even more tenuous than the suggestion of an Irish

origin for the towers appears to me a theory recently

advanced by Hans Reinhardt,[9]

who sketches a developmental

line leading to the towers of St. Gall from the

triumphal columns of Rome through the intermediary

forms of the Mohammedan minaret (fig. 86) and certain

funerary light towers (fig. 87), especially well-attested in

twelfth-century western France. Leaving entirely to one

side the question of the very doubtful connection of all these

disparate architectural entities, it must be stressed that

there is nothing in the Plan itself that would suggest that

the two towers of the Church were used either as call

towers, from which the monks sang their daily vigils and

announced the hours of prayer (in the sense in which this

was done in the Mohammedan ritual), or as light towers on

the top of which a lantern was lit at night in commemoration

of the dead. The author of the Plan is very specific.

The purpose of the towers, he tells us, is "to survey the

entire orbit [of the monastery] from above" (ad uniuersa

super inspicienda); this defines them as places of surveillance

—surveillance in the sense of "watch over approaching

danger." The use of the term uniuersa suggests that the

protective function of the towers was meant to extend

beyond the physical plant of the monastery; and the

patronage of the archangels Michael and Gabriel tends to

strengthen this view. Michael, through his defeat of

Lucifer, became the embodiment of the forces of light

prevailing over the powers of darkness; Gabriel was the

announcer of the human incarnation of the Saviour. Both

angels, through these accomplishments, became in a special

sense the protectors and guardians of the Church. All over

the Western world, St. Michael was venerated in sanctuaries

built on high-lying ground, on mountains, in the

upper stories of the western avant-corps of churches, or in

the steeples of towers. From there he pits himself against

the forces of darkness that rush against the House of the

Lord from the west.[10]

On coins and in medieval manuscript

illuminations Rome and Jerusalem, the two terrestrial

counterimages of the City of God, were represented by a

gate flanked by two defending towers.[11]

In like manner, on

the Plan of St. Gall, the Church is defended by its two

protective towers against the evil that rushes against it.

On the widespread veneration of St. Michael in sanctuaries located

on mountains or in the upper stories of towers, see Ostendorf, 1922, 44ff

and 287ff; Vallery-Radot, 1929, 453-78; O. Gruber, 1936, 149-73;

Lehmann Brockhaus, 1938, 69-70, note 85; Schmidt, 1956, 380; and

Fuchs, 1957, 6 and 30.

BELL TOWERS OR TOWERS OF DEFENSE

AND SURVEILLANCE?

It cannot be stressed with sufficient strength that the

explanatory titles associated with these towers fail to make

any reference to campana, signa, or tintinnabula; and for

that reason they cannot be interpreted as bell towers. On

purely historical grounds this would be a perfectly feasible

assumption. Bells set in motion with ropes, to mark the

various phases of the divine services or other festive events,

are mentioned at various places in the History of the

Franks of Gregory of Tours (d. 593/94). In the course of

the seventh and eighth centuries the evidence in contemporary

sources attesting their existence increases so

markedly that it can safely be assumed that they existed elsewhere.[12]

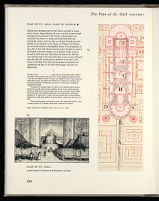

82. PLAN OF ST. GALL. PLAN OF CHURCH

Shaded areas distinguish parts of the Church accessible to monks,

and to laymen. Approaching by the access road (A) cutting through

the large service yard west of the Church, visiting pilgrims are

received by the Porter in a square porch (B) lying before the

semicircular atrium, and from there are directed through two more

porches (C, D), the poor to the Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers,

the rich to the House for Distinguished Guests. Two passageways no

more than 7½ feet wide channel entering laymen through the aisles of

the Church, across the transept, to a U-shaped corridor crypt at

the end of which they may kneel before the tomb of St. Gall (E).

Two reserved areas in the nave allow them to hear sermons delivered

from the ambo (F), attend services celebrated at the altar of the

Savior at the Holy Cross (G), and participate in baptismal rites

conducted at the altar of SS John the Evangelist and John the

Baptist (H).

The pale red tint defines the area of the church proper. This, in

its totality was the province of the monk. Part of it he willingly shared with laymen

so that they also might be touched by mystery and deepened in faith. Those areas of the

church where layman and pilgrim were welcome and to which their movements were

restricted for enjoyment, contemplation, and prayer are indicated in a meandering

vignetted black stipple:

The pattern of circulation began at the Entry Porch, flowed along the aisles of

the church, passed by shrines and nave columns all with carved capitals supporting

arcades and walls above the arcades aglow with the color of painting. Then reaching

the crossing square, the circulation descended by stairs beneath apse and high altar

(dedicated to St. Mary and St. Gall) to the crypt passage where at point of climax,

illuminated by candle light, immersed in vibrant shadow, could be seen the tomb of St.

Gall.

This was moving theater and impressive, even to the sophisticated viewer. In such

a setting the Order of St. Benedict would gather momentum for centuries.

SCALE OF PLAN: 3/10 ORIGINAL SIZE (1:192 × 0.3 = 1:640)

83. PLAN OF ST. GALL

ACCESS ROAD TO CHURCH & MONASTERY GROUNDS

the towers of the Plan of St. Gall do not contain any suggestion

that they were meant to house bells; and there is

some doubt in my mind that any bells suspended in these

towers could have successfully fulfilled their function. The

use of these instruments implies an element of timing

which requires that the brother charged with the task of

ringing them be within sight or hearing of the officiating

priest.[13] Bell ringers stationed in the isolated towers of the

Church of the Plan of St. Gall could have neither seen nor

heard the priest.[14]

For Tours see Otte, 1884, 9 and Mon. Germ. Hist., Script. Rer.

Merov., I:1, 1885, 258; for the seventh and eighth century sources see

Otte, op. cit., 12ff and von Sommerfeld, 1906, 198ff.

The monastic consuetudines of the period abound with references

to bells and tell us exactly at what point in the divine service they were

struck. Bells of "small," "middling," and "large" size (signum pussillum,

signum modicum, signum majus) are mentioned in the Consuetudines

Cluniacenses antiquores, which reflected a considerably earlier tradition

with which Benedict of Aniane was familiar. See Cons. mon., ed. Bruno

Albers, II, 1905, 2 and 3. For other references to bells, see under the

words campana, signum, tintinnabulum, cymbalum in the indices of Corp.

cons. mon., 1963; Schlosser, 1896; and Cons. mon., I-V, 1900-12; as well

as in Du Cange's Glossarium.

A rectangular bell of Irish design and probably Irish provenience is on

exhibit in the Stiftsbibliothek of St. Gall. It was used, according to tradition,

by St. Columban and St. Gall in a cell which these two missionaries

occupied from 610 to 612 in the vicinity of Bregenz (Gallenstein). The bell

is of sheet iron. It is 33 cm. high, has a diameter at the bottom of 15 cm. ×

23 cm. and at the top of 11 cm. × 17 cm. It was never suspended in a

bell tower, but apparently held in the hand and struck on one of its outer

surfaces with the aid of a club or rod. Before the introduction of cast

bronze bells, hammered iron bells of this type were used not only in

Ireland, but also on the Continent. Walahfrid Strabo tells us that they

were called "signals" (signa) and used to announce the hours of the

divine service (quibusdam pulsibus significantur horae). The "St. Gall-Bell

of Bregenz" is dealt with by Duft, 1966, 425-36, where, incidentally,

attention is drawn to the fact that the squarish design of modern Alpine

cow bells is derived from that of the service bells used in the early Irish

monasteries of the Alpine forelands. The spread of the form has an

interesting etymological parallel in the propagation of the word with

which this object is designated: the German word Glocke comes from

Irish clogg through the intermediary stages of Medieval Latin clocca and

Old High German glokka (Duft, op. cit., 431).

From a strictly practical point of view, a small towerlike superstructure

over the transept would have provided a more suitable solution

for placing bells to announce the various phases of the liturgical cycle

than two isolated towers standing at a distance of over 300 feet from the

high altar. In large metropolitan churches, as well as in smaller parish

churches which were designed primarily for the worship of laymen,

conditions may have been different.

THE EIGHT-LOBED ROSETTE:

A STELLAR AND APOTROPAIC SYMBOL

One of the smaller unexplained motifs of the Plan of St.

Gall is the eight-lobed rosette that decorates the area in the

center of the two church towers which corresponds to the

open shaft of its stairs. The same motif appears on the two

poultry houses in connection with a circular "tower-like"

projection.[15]

It has been interpreted in various ways, as

"being of no significance,"[16]

as "indicating the conical

roof of the building, or its ornamental finial,"[17]

and as

representing "the decorative design in the shingles which

cover the roof of the building."[18]

None of these explanations

seems convincing. The motif, rather, belongs to an

old and widespread family of stellar symbols, the origins

of which reach back into antiquity. Eight- or six-lobed

rosettes, as symbols of the stellar nature of God, are a

common occurrence in Sumerian, Babylonian, Jewish, and

Roman art (fig. 88). The motif was quickly absorbed into

the Christian cult, as a reference to the celestial nature of

the new god, and subsequently became so closely associated

with the cross of Christ as to be practically interchangeable

with it (figs. 89 and 90).[19]

The symbol placed its bearers

under the stellar protection of Christ, and through a

vernacular vulgarization of its original meaning eventually

assumed the role of a charm against lightning and fire, or

against disease affecting the health of livestock. The

symbol appears frequently in monastic medieval tithe

barns (fig. 91),[20]

and survives to this very day in the

repertoire of decorative motifs, which are locally referred

to as "hex-signs," on numerous barns in the state of

Pennsylvania, in the United States of America (fig. 92).[21]

Concerning the use of the rosette motif in Syrian, Coptic, and North

African Early Christian art, see Mellinkoff, 1947; in Visigothic art, Puig i

Cadafalch, 1961, 53ff; in Merovingian art, Benoit, 1959, 49-51; and in

Anglo-Norman art, Keyser, 1927, passim.

On one of the large bracing struts of the timber frame of the

thirteenth-century Monastery Barn of Ter Doest, in Maritime Flanders,

Belgium, there are seven six-lobed rosettes. For a brief account of this

barn, see Horn and Born, 1965.

With regard to the so-called hex signs of the Pennsylvania Dutch

barns, see Mahr, 1945, 1-32; Morrison, 1952, 545-46; and Sloane, 1954,

66ff.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||