The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| II. |

| II. 1. | II. 1 |

| II.1.1. |

| II.1.2. |

| II.1.3. |

| II.1.4. |

| II.1.5. |

| II.1.6. |

| II.1.7. |

| II.1.8. |

| II.1.9. |

| II.1.10. |

| II.1.11. |

| II.1.12. |

| II.1.13. |

| II. 2. |

| II. 3. |

| III. |

| IV. |

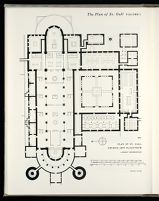

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

II. 1

DESCRIPTION

INTRODUCTION

THE Church of the Plan of St. Gall (figs. 82, 84, 93, and 99) is an aisled cruciform structure with an apse at either

end, an eastern and western paradise, and two detached round towers on its entrance side. Its most remarkable

feature, historically, apart from its length, is the fact that its layout is based on a system of squares that bears

startling resemblance to the so-called square schematism of the German Romanesque. This system is here carried

out with a logic and consistency unparalleled in any of the Carolingian churches actually constructed, with the sole

exception, possibly, of the cathedral and monastery church that Archbishop Hildebold (d. 819) built at Cologne

sometime after the year 800 (figs. 16-18).[1]

The Church measures 300 feet from apse to apse.[2]

Its nave and transept have the same width, 40 feet, and thus

their area of intersection, the crossing, forms a square. The fore choir and two transept arms repeat the dimensions

of the crossing square, and the dimensions of the nave are so arranged as to cover a surface area of exactly four-and-one-half

times the size of the crossing square. The width of the aisles, 20 feet, is half the width of the nave (40 feet);

the interstices between the columns which support the clerestory wall on either side of the nave are spaced at intervals

of 20 feet on center.

The most striking feature to a modern visitor, were he able to enter this church, would be the many screens and

railings which divide the interior into separate areas for worship (figs. 82, 84, 93, and 99). In the time of Constantine

the Great, the Christian house of worship had only one altar, and its nave and aisles were so arranged

architecturally that the entering crowd could move from the entrances to the altar in a straight, continuous movement

that paralleled the columnar rhythm of the arcades supporting its walls (fig. 81). No barriers blocked the path

of those proceeding to the altar until they reached the chancel railing, which screened off the space for the officiating

clergy. By contrast, the Church of the Plan of St. Gall is furnished with seventeen altars (nineteen, if we add the

altars of its towers), but except for a narrow passage in each aisle by which the pilgrims gain access to the tomb of

St. Gall in the crypt, only one-sixth of the entire surface area of the Church is open to laymen (fig. 82): a portion

of the nave of the Church, 40 feet wide and 110 feet long, extending from the second pair of columns to halfway

eastern half for services held for pilgrims, and for the Monastery's serfs and workmen. All the remaining portions of

the Church—transept, presbytery, the terminal bays of the nave, most of the aisles, and the two apses—are screened

off for exclusive use by the monks and their clergy.

On the discrepancies between the Church as it was drawn and the

form it would have attained had it been modified in light of its explanatory

title, see above, pp. 77ff.

II.1.1

APPROACH

The official approach to the Church, which is also the only

legitimate access to the Monastery grounds, is a road 25 feet

wide and 145 feet long. This road is coaxial with the Church

and intersects, to the west of it, the large tract of land that

accommodates the houses for the monastic livestock and

their keepers, and the houses for servants and knights who

travel in the emperor's following (fig. 83). The road is

identified by a distich written in capitalis rustica:

OMNIBUS AD SCM TURBIS PATET HAEC UIA TEMPLUM

QUO SUA UOTA FERANT UNDE HILARES REDEANT

THIS IS THE ROAD OF ACCESS TO THE CHURCH IN

WHICH ALL FOLK MAY WORSHIP THAT THEY MAY LEAVE REJOICING

There must have been other entrances to the service yards

for the passage of livestock, for hauling in the harvest and

wine on wagons or carts, and for the delivery of tithes from

outlying estates, but these passageways were not open to

pilgrims. Since the Plan does not tell us anything about the

outer wall enclosure, we do not know where such entrances

might have been. As the yards that lie to the west of the

Church are completely surrounded by fences, the Monastery

may not have required an outer gate.

II.1.2

ATRIUM

The gate to the Monastery is a large semicircular atrium,

which lies immediately west of the Church (fig. 84). This

installation comes under the jurisdiction of the Porter

(portarius) and the master of the paupers (procurator pauperum).

It is provided with three porches, in which the

visitors are received and screened for dispersion to their

respective quarters. The first of these three porches faces

west and carries the inscription:

Adueniens aditum populus hic cunctus habebit

Here all the arriving people will find their entry

The other two, facing south and north, lie at the ends of the

atrium. The one to the north gives access to the grounds of

the House for Distinguished Guests and the Outer School.

It is inscribed with a distich that reads:

Exi & hic hospes uel templi tecta subibit

Discentis scolae pulchra iuuenta simul[3]

At this point the guests will either go out or enter

quietly under the roof of the church.

Likewise the noble youth who attend the academic school.

The southern porch opens onto the grounds of the Hospice

for Pilgrims and Paupers and also serves as entryway for

the Monastery's serfs and workmen:

Tota monasterio famulantum hic turba subintret

Here let the entire crowd of the servants enter the

monastery quietly

The lodgings of the porter and of the almoner are contiguous

to these porches. That of the porter abuts the

northern aisle of the Church, that of the almoner the

southern.[4]

The principal body of the atrium consists of a covered

semicircular gallery that gives access to the aisles of the

Church. The outer perimeter of this gallery is formed by a

solid wall; its inner perimeter consists of an open arcade

with arches rising from square piers. A hexameter inscribed

into the gallery in capitalis rustica states:

HIC MURO TECTUM IMPOSITUM

PATET ATQUE COLUMNIS

HERE A ROOF EXTENDS, SUPPORTED

BY A WALL AND BY COLUMNS

A title entered in the interstices of the arcades that support

the roof of the covered walk ascribes to them an inter-columniary

distance of 10 feet:

Has interque pedes denos moderare columnas

Between these columns count ten feet

The gallery encloses concentrically an open plot of land

covered with grass, whose purpose is explained by another

hexameter, again in capitalis rustica:

HIC PARADISIĀCUM SINE TECTO

STERNITO CAP̄UM[5]

HERE STRETCH OUT A PARKLIKE

SPACE WITHOUT A ROOF

The first three lines of this verse, as has been noted above, are written

by the hand of the second scribe, the last three by the hand of the main

scribe. See pp. 13ff.

"Paradisus," a word of Persian origin, denoting a royal park or enclosed

pleasure garden, used in the Greek Old Testament in the sense of

"green space" or "park" for the Garden of Eden, and subsequently, in a

more supernatural sense, for the paradise of Hope, situated not on earth

but in heaven. In architecture it is used as a name for the hallowed spaces,

encircled by porticoes, in front of the entrance of temples and churches.

"Fecit et atrium ante ecclesiam, quod nos Romana consuetudine Paradisum

vocitamus." Leo of Ostia, 1115; for other sources, see Du Cange, Glossarium,

s.v. "paradisus." For later uses of the term, see Parker, 1850,

338-39.

II.1.3

TOWERS

Two doors in the outer atrium wall, placed midway

between the outer porch and the two inner porches give

access to two detached circular towers. Their diameter is

30 feet and their closest point lies at a distance of 7½ feet

from the outer atrium wall. Both towers are ascended by

winding stairs, suggested graphically by spirals and verbally

by an inscription in the northern tower (from the hand

of the main scribe) which reads: "Ascent by a spiral

staircase to survey the entire orbit [of the monastery] from

above" (ascensus per c·/·ocleam ad uniuersa super inspicienda).

A title in the southern tower (written by the same hand)

simply states: "another one of the same kind" (alter

similis). The northern tower has in its summit an altar

dedicated to the archangel Michael (in summitate altare sci

Michahelis archangeli), the southern tower, an altar dedicated

to archangel Gabriel (in fastigio altare sci Gabrihelis

archangeli). These last two titles are written by the hand

of the second scribe in such a pale shade of ink that they

are barely legible.[6]

CONNECTION WITH IRELAND?

The purpose of the two detached towers of the Plan of

St. Gall has been the subject of a considerable amount of

controversy. J. R. Rahn suggested a connection with the

round towers of Ireland (fig. 85).[7]

But it appears that no

circular towers are known to have existed in Ireland early

enough to have been copied on the Plan of St. Gall.[8]

Moreover,

there is nothing else in the architectural layout of the

Plan that would suggest any special ties with Ireland; and

the general trend of the monastic reform movement, to

which the Plan owes its existence, was away from the Irish

tradition rather than toward it.

CALL TOWERS OR FUNERARY LIGHT TOWERS?

Even more tenuous than the suggestion of an Irish

origin for the towers appears to me a theory recently

advanced by Hans Reinhardt,[9]

who sketches a developmental

line leading to the towers of St. Gall from the

triumphal columns of Rome through the intermediary

forms of the Mohammedan minaret (fig. 86) and certain

funerary light towers (fig. 87), especially well-attested in

twelfth-century western France. Leaving entirely to one

side the question of the very doubtful connection of all these

disparate architectural entities, it must be stressed that

there is nothing in the Plan itself that would suggest that

the two towers of the Church were used either as call

towers, from which the monks sang their daily vigils and

announced the hours of prayer (in the sense in which this

was done in the Mohammedan ritual), or as light towers on

the top of which a lantern was lit at night in commemoration

of the dead. The author of the Plan is very specific.

The purpose of the towers, he tells us, is "to survey the

entire orbit [of the monastery] from above" (ad uniuersa

super inspicienda); this defines them as places of surveillance

—surveillance in the sense of "watch over approaching

danger." The use of the term uniuersa suggests that the

protective function of the towers was meant to extend

beyond the physical plant of the monastery; and the

patronage of the archangels Michael and Gabriel tends to

strengthen this view. Michael, through his defeat of

Lucifer, became the embodiment of the forces of light

prevailing over the powers of darkness; Gabriel was the

announcer of the human incarnation of the Saviour. Both

angels, through these accomplishments, became in a special

sense the protectors and guardians of the Church. All over

the Western world, St. Michael was venerated in sanctuaries

built on high-lying ground, on mountains, in the

upper stories of the western avant-corps of churches, or in

the steeples of towers. From there he pits himself against

the forces of darkness that rush against the House of the

Lord from the west.[10]

On coins and in medieval manuscript

illuminations Rome and Jerusalem, the two terrestrial

counterimages of the City of God, were represented by a

gate flanked by two defending towers.[11]

In like manner, on

the Plan of St. Gall, the Church is defended by its two

protective towers against the evil that rushes against it.

On the widespread veneration of St. Michael in sanctuaries located

on mountains or in the upper stories of towers, see Ostendorf, 1922, 44ff

and 287ff; Vallery-Radot, 1929, 453-78; O. Gruber, 1936, 149-73;

Lehmann Brockhaus, 1938, 69-70, note 85; Schmidt, 1956, 380; and

Fuchs, 1957, 6 and 30.

BELL TOWERS OR TOWERS OF DEFENSE

AND SURVEILLANCE?

It cannot be stressed with sufficient strength that the

explanatory titles associated with these towers fail to make

any reference to campana, signa, or tintinnabula; and for

that reason they cannot be interpreted as bell towers. On

purely historical grounds this would be a perfectly feasible

assumption. Bells set in motion with ropes, to mark the

various phases of the divine services or other festive events,

are mentioned at various places in the History of the

Franks of Gregory of Tours (d. 593/94). In the course of

the seventh and eighth centuries the evidence in contemporary

sources attesting their existence increases so

markedly that it can safely be assumed that they existed elsewhere.[12]

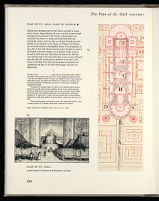

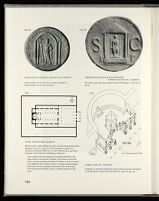

82. PLAN OF ST. GALL. PLAN OF CHURCH

Shaded areas distinguish parts of the Church accessible to monks,

and to laymen. Approaching by the access road (A) cutting through

the large service yard west of the Church, visiting pilgrims are

received by the Porter in a square porch (B) lying before the

semicircular atrium, and from there are directed through two more

porches (C, D), the poor to the Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers,

the rich to the House for Distinguished Guests. Two passageways no

more than 7½ feet wide channel entering laymen through the aisles of

the Church, across the transept, to a U-shaped corridor crypt at

the end of which they may kneel before the tomb of St. Gall (E).

Two reserved areas in the nave allow them to hear sermons delivered

from the ambo (F), attend services celebrated at the altar of the

Savior at the Holy Cross (G), and participate in baptismal rites

conducted at the altar of SS John the Evangelist and John the

Baptist (H).

The pale red tint defines the area of the church proper. This, in

its totality was the province of the monk. Part of it he willingly shared with laymen

so that they also might be touched by mystery and deepened in faith. Those areas of the

church where layman and pilgrim were welcome and to which their movements were

restricted for enjoyment, contemplation, and prayer are indicated in a meandering

vignetted black stipple:

The pattern of circulation began at the Entry Porch, flowed along the aisles of

the church, passed by shrines and nave columns all with carved capitals supporting

arcades and walls above the arcades aglow with the color of painting. Then reaching

the crossing square, the circulation descended by stairs beneath apse and high altar

(dedicated to St. Mary and St. Gall) to the crypt passage where at point of climax,

illuminated by candle light, immersed in vibrant shadow, could be seen the tomb of St.

Gall.

This was moving theater and impressive, even to the sophisticated viewer. In such

a setting the Order of St. Benedict would gather momentum for centuries.

SCALE OF PLAN: 3/10 ORIGINAL SIZE (1:192 × 0.3 = 1:640)

83. PLAN OF ST. GALL

ACCESS ROAD TO CHURCH & MONASTERY GROUNDS

the towers of the Plan of St. Gall do not contain any suggestion

that they were meant to house bells; and there is

some doubt in my mind that any bells suspended in these

towers could have successfully fulfilled their function. The

use of these instruments implies an element of timing

which requires that the brother charged with the task of

ringing them be within sight or hearing of the officiating

priest.[13] Bell ringers stationed in the isolated towers of the

Church of the Plan of St. Gall could have neither seen nor

heard the priest.[14]

For Tours see Otte, 1884, 9 and Mon. Germ. Hist., Script. Rer.

Merov., I:1, 1885, 258; for the seventh and eighth century sources see

Otte, op. cit., 12ff and von Sommerfeld, 1906, 198ff.

The monastic consuetudines of the period abound with references

to bells and tell us exactly at what point in the divine service they were

struck. Bells of "small," "middling," and "large" size (signum pussillum,

signum modicum, signum majus) are mentioned in the Consuetudines

Cluniacenses antiquores, which reflected a considerably earlier tradition

with which Benedict of Aniane was familiar. See Cons. mon., ed. Bruno

Albers, II, 1905, 2 and 3. For other references to bells, see under the

words campana, signum, tintinnabulum, cymbalum in the indices of Corp.

cons. mon., 1963; Schlosser, 1896; and Cons. mon., I-V, 1900-12; as well

as in Du Cange's Glossarium.

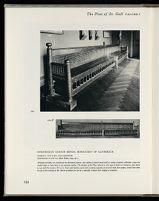

A rectangular bell of Irish design and probably Irish provenience is on

exhibit in the Stiftsbibliothek of St. Gall. It was used, according to tradition,

by St. Columban and St. Gall in a cell which these two missionaries

occupied from 610 to 612 in the vicinity of Bregenz (Gallenstein). The bell

is of sheet iron. It is 33 cm. high, has a diameter at the bottom of 15 cm. ×

23 cm. and at the top of 11 cm. × 17 cm. It was never suspended in a

bell tower, but apparently held in the hand and struck on one of its outer

surfaces with the aid of a club or rod. Before the introduction of cast

bronze bells, hammered iron bells of this type were used not only in

Ireland, but also on the Continent. Walahfrid Strabo tells us that they

were called "signals" (signa) and used to announce the hours of the

divine service (quibusdam pulsibus significantur horae). The "St. Gall-Bell

of Bregenz" is dealt with by Duft, 1966, 425-36, where, incidentally,

attention is drawn to the fact that the squarish design of modern Alpine

cow bells is derived from that of the service bells used in the early Irish

monasteries of the Alpine forelands. The spread of the form has an

interesting etymological parallel in the propagation of the word with

which this object is designated: the German word Glocke comes from

Irish clogg through the intermediary stages of Medieval Latin clocca and

Old High German glokka (Duft, op. cit., 431).

From a strictly practical point of view, a small towerlike superstructure

over the transept would have provided a more suitable solution

for placing bells to announce the various phases of the liturgical cycle

than two isolated towers standing at a distance of over 300 feet from the

high altar. In large metropolitan churches, as well as in smaller parish

churches which were designed primarily for the worship of laymen,

conditions may have been different.

THE EIGHT-LOBED ROSETTE:

A STELLAR AND APOTROPAIC SYMBOL

One of the smaller unexplained motifs of the Plan of St.

Gall is the eight-lobed rosette that decorates the area in the

center of the two church towers which corresponds to the

open shaft of its stairs. The same motif appears on the two

poultry houses in connection with a circular "tower-like"

projection.[15]

It has been interpreted in various ways, as

"being of no significance,"[16]

as "indicating the conical

roof of the building, or its ornamental finial,"[17]

and as

representing "the decorative design in the shingles which

cover the roof of the building."[18]

None of these explanations

seems convincing. The motif, rather, belongs to an

old and widespread family of stellar symbols, the origins

of which reach back into antiquity. Eight- or six-lobed

rosettes, as symbols of the stellar nature of God, are a

common occurrence in Sumerian, Babylonian, Jewish, and

Roman art (fig. 88). The motif was quickly absorbed into

the Christian cult, as a reference to the celestial nature of

the new god, and subsequently became so closely associated

with the cross of Christ as to be practically interchangeable

with it (figs. 89 and 90).[19]

The symbol placed its bearers

under the stellar protection of Christ, and through a

vernacular vulgarization of its original meaning eventually

assumed the role of a charm against lightning and fire, or

against disease affecting the health of livestock. The

symbol appears frequently in monastic medieval tithe

barns (fig. 91),[20]

and survives to this very day in the

repertoire of decorative motifs, which are locally referred

to as "hex-signs," on numerous barns in the state of

Pennsylvania, in the United States of America (fig. 92).[21]

Concerning the use of the rosette motif in Syrian, Coptic, and North

African Early Christian art, see Mellinkoff, 1947; in Visigothic art, Puig i

Cadafalch, 1961, 53ff; in Merovingian art, Benoit, 1959, 49-51; and in

Anglo-Norman art, Keyser, 1927, passim.

On one of the large bracing struts of the timber frame of the

thirteenth-century Monastery Barn of Ter Doest, in Maritime Flanders,

Belgium, there are seven six-lobed rosettes. For a brief account of this

barn, see Horn and Born, 1965.

With regard to the so-called hex signs of the Pennsylvania Dutch

barns, see Mahr, 1945, 1-32; Morrison, 1952, 545-46; and Sloane, 1954,

66ff.

I follow the reading suggested by Johannes Duft; cf. I. Müller, in

Studien, 1962, 165; and Reinhardt, 1952, 10.

II.1.4

WESTERN APSE

ALTAR OF ST. PETER

The western apse (exedra) of the Church is dedicated to St.

Peter. Its floor is raised above the level of the nave by two

steps (gradus) and it is furnished with a wall bench which

follows the apse in its entire circumference. A square in the

center of the apse is designated as the altar of St. Peter by a

hexameter:

Hic Petrus eclae pastor sortitur honorē

Here Peter, the shepherd of the Church, allots

honor

This location of the altar of St. Peter at the western end

of the Church, in counterposition to that of St. Paul at the

eastern end, is doubtlessly patterned after the churches of

these two primary apostles in Rome, where the altar of St.

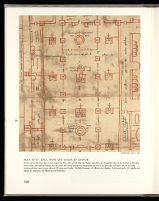

84. PLAN OF ST. GALL, ATRIUM, TOWERS, AND WESTERN PART OF CHURCH

This layout, of consummate beauty and unique in its own period, has only one parallel in Early Christian architecture (fig. 161). The Church of

the Plan is preceded by a semicircular atrium surrounding an open pratellum, which is in turn flanked by two imposing circular towers built for symbolic

rather than functional purposes. There is no façade as in the great Early Christian prototype churches designed to receive huge metropolitan crowds.

The Church of the Plan of St. Gall is constructed for monks and—inward-turned—faces the outside world with a counter apse housing the altar

of St. Peter.

The importance of the cult of St. Peter and St. Paul and the

close association with Rome that it suggests finds expression

in the fact that their altars are installed in the apses,

where they are second only to the high altar. They are

smaller than the high altar but larger than any of the other

altars, including the altar of the Holy Cross in the center of

the nave of the Church.

A further sign of distinction is that their function is

expressed in the form of a verse rather than the simple

word altare by which the altars in the transept and the nave

are designated. Poeschel's suggestion that the squares in the

two apses of the Church should be interpreted as "pulpits"

or "lecterns" rather than as altars appears to me untenable,

both in the light of their inscriptions[23]

and in view of their

location. The apse is the place par excellence for altars.[24]

Moreover, the raised floor level, the semicircular wall

bench for the worshiping monks, and the carefully segregated

choir (chorus) in the two contiguous bays of the nave

have distinct eucharistic implications and would be meaningless

were they not connected liturgically with the rituals

performed at an altar (see fig. 84).

As correctly and strongly stressed by Poeschel, 1956, 135-36. See

also Iso Müller, in Studien, 1962, 139; and Arens, 1938, 61, note 89.

Poeschel, loc. cit. On the eucharistic implications of the word

honores, used in the inscriptions of both altars, see Father Iso Müller, op.

cit., 137-38. Poeschel is disturbed by the fact that the squares in the

apses of St. Peter and St. Paul are not inscribed with the word altare, as

most of the other altars are. If they were meant to serve as lecterns or

pulpits for special devotional functions, as Poeschel suggests, it should be

equally disturbing that they are not inscribed with the word analogium

or ambo, as are all the other pulpits or lecterns of the Plan of St. Gall

(two easternmost bays of the nave and Refectory); see below, p. 136.

There was no need to identify the altars of the two primary apostles with

the word altare, as their purpose was already expressed in the more

explicit form of verse. The fact that the two altars are not decorated with

a cross does not militate against this interpretation. Five other altars in

the Church (including the all-important high altar) lack this sign, as

Poeschel himself has pointed out. Nor should it come as a surprise that

the altars in the two apses are not enclosed by any chancel barriers. They

stand in areas that are not easily accessible to the secular visitors of the

Church. The eastern apse is entirely outside the reach of any layman, and

the western apse was undoubtedly protected by a rail, like the choir in

front of it.

Of scores of examples that could be cited, I refer only to the Abbey

Church of St.-Riquier (altar of St. Richarius in the eastern apse), the

Abbey Church of Fulda (altar of the Saviour), not to speak of the great

Constantinian prototype church, Old St. Peter's (altar of St. Peter in the

west apse); see Effman, 1912, fig. 8; Beumann and Grossmann, 1949, 45,

figs. 3 and 4; and Toynbee and Ward-Perkins, 1953, 202, fig. 20, and

215, fig. 22.

II.1.5

AISLES

The apse with the altar of St. Peter would not have been

readily accessible to visiting pilgrims and noblemen; on the

contrary, those who entered the Church at the two extreme

corners of the aisles found their progress blocked in the

nave by the choir of St. Peter, and in each of the aisles by

four altars, forcing them into a narrow passageway along

the arcades, through which they could move eastward to

gain access to the sanctuary in the crypt of the Church. The

altars of the aisles are located at intervals of 40 feet and are

carefully aligned with every second pair of nave columns.

Each of these altars is surmounted by a cross, shown in

horizontal projection. Each altar is enclosed by its own

chancel barrier that extends laterally toward the walls of

the church, thus dividing the floor space of the outer two-thirds

of the aisles into separate stations for worship.

The altars of the northern aisle, as we move west to east,

are dedicated as follows: the first one, jointly to SS. Lucia

and Cecilia (altar s̄c̄ cie & cecilie); the second, to the Holy

Innocents (altare scōr̄r̄ innocent); the third, to St. Martin

(altare sci martini); the fourth, to St. Stephen (altare s̄c̄

stephani mar̄). The dedications of the corresponding altars

in the southern aisle are: the first one, jointly to SS. Agatha

and Agnes (altare sctar agtae & agnet);[25]

the second, to St.

Sebastian (altare sci sebastiani); the third, to St. Mauritius

(altare sci maricii); and the fourth, to St. Lawrence (altare

sancti laurenci). The names of these saints are written in

the barely legible pale-brown ink used by the second

scribe. The choice for the patrocinium of these altars, if

Father Iso Müller is correct,[26]

was influenced by the layout

of the altars in the Abbey Church of St.-Riquier, and in

certain cases, where parallels with St.-Riquier cannot be

drawn, by the existence in the monastery of St. Gall of

relics not available elsewhere.

According to a new reading proposed by Bischoff (cf. Müller, in

Studien, 1962, 158-59). Earlier authors interpreted this title as reading

SS. Catherine and Agnes (altare sc̄tar̄ catherine & agnetis); cf. Reinhardt,

1952, 10.

II.1.6

NAVE

The nave (figs. 84, 93 and 99) is 40 feet wide and 180 feet

long. Its clerestory rests on nine arcades, with columns

spaced at intervals of 20 feet on center. In three places

the nave is blocked in its entirety by cross partitions which

make it impossible for anyone at any point within the

nave to move in a straight line from the western apse to

the transept. The first of these screens connects the second

pair of columns; the second lies in line with the fifth pair;

and the third, midway between the seventh and eighth pair.

In addition, in three places, the nave is also railed off from

the aisles: in the third arcade, the sixth, and the last one-and-a-half

arcades. The spaces thus segregated isolate the

areas reserved for the monks from those accessible to the

laymen.

CHOIR OF ST. PETER

Between the two westernmost arcades of the nave an area

22½ feet wide and 32½ feet long is screened off to serve as a

choir (chorus) for the monks who chant before the altar of

St. Peter. The railing of this choir has a wide central

opening toward the altar of St. Peter, and two narrow

lateral passages at the opposite end. What such choir

85. MEDIEVAL ROUND TOWER, NORTHWEST CORNER OF CATHEDRAL

VALE OF GLENDALOUGH, WICKLOW, IRELAND

The Old Irish word for these towers, some of which rise to over 100 feet, is CLOIGTHEACH or "bell tower;" but the placement in most of them

of entrances well above ground level suggests they were used as places of refuge during attack. The earliest date from about 900.

choir and altar railings of the churches of Santa Sabina and

San Clemente in Rome, as well as from numerous fragments

of other screens of this type in Greek, Syrian, and

Palestinian churches. The arrangement is traditional. We

are showing as a typical example a reconstruction of the

presbytery of the Basilica of Thasos, Macedonia (fig. 94),

which also displays the Early Christian prototype for the

semicircular wall benches in the two apses of the Church

of the Plan of St. Gall.[27]

After Orlandos, II, 1954, 528, fig. 493. For Santa Sabina in Rome

see Deichmann, 1958, pl. 28; for San Clemente, Matt, 1950, pl. 99; for

other Macedonian examples, Orlandos, II, 1954, 526-27, figs. 490-92.

BAPTISMAL FONT AND ALTAR

The space between the first and second cross-partitions

of the nave serves as a baptistery. In the westernmost bay

is the baptismal font of the Church, and in the bay next to

it, an altar dedicated jointly to SS. John the Baptist and

John the Evangelist (altare sc̄ī iohannis & sc̄ī iohī euangelistae).

The baptismal font (fons) is marked by two concentric

circles and the hexameter:

Ecce renascentes susceptat x̄p̄s̄ alumnos

See, it is here that Christ receives reborn disciples

Francis Bond interpreted these two rings as representing

"either a circular piscina or a circular font."[28]

The first

proposition in this alternative must, I think, be abandoned.

Baptismal fonts constructed in the form of piscinae sunk

below the level of the pavement were common in Early

Christian times and during the period of conversion of the

barbaric tribes, when the majority of the people to be

baptized were adults. But in Carolingian times (with the

notable exception of the conversion of the Saxons, as Bond

himself points out),[29]

the baptism of adults had become

unusual. Babies,[30]

unable to stand upright, had to be dipped

into the water by the officiating priest and this could be

done successfully only if the water level were brought

within reasonable range of the priest as he bent over to

perform the ceremonial immersion of the child. The

elevated tub-shaped water font was the logical answer to

this need.

A convention of bishops held at the banks of the Danube

River in the summer of 796 reaffirmed an old ecclesiastical

directive according to which baptismal rites could be held

only at Pentecost and Easter, except in cases of extreme

urgency.[31]

This may explain the large dimensions of the

font of the Plan of St. Gall, whose diameter runs over 6 feet.

That same convention took it for granted that the baptismal

rite should be performed "in a font, or some such

vessel, in which one can be immersed thrice in the name of

the Holy Trinity" (in fonte, vel tali vase, ubi in nomine

sanctae trinitatis trina mersio fieri possit).[32]

Baptismal fonts were in general made of stone, but a

directive issued in 852 by Bishop Hincmar of Reims orders

that "if a parish church cannot afford a baptismal font of

stone, it must provide for other suitable substitutes,"[33]

which can only refer to portable wooden tubs. A charming

picture of a baptismal rite performed in such a temporary

contrivance may be found in one of the marginal illuminations

of the Luttrell Psalter (fig. 95).[34]

Circular fonts of

stone exist in many places; like the font of the Plan of St.

Gall, they usually are raised on a plinth. I show as typical

examples (fig. 96 and 97) a highly decorated font in the

church of Deerhurst, Gloucestershire, England, of pre-Conquest

date,[35]

and a larger cylindrical font of around

1100 now in the possession of Dr. Peter Ludwig, Aachen.[36]

In the Middle Ages the baptismal font usually stood in

the northern aisle of the church close to the western

entrance.[37]

The arrangement on the Plan of St. Gall where

the font is placed into the very axis of the church is unusual[38]

and probably owes its existence to the desire to

restrict the services for the laymen to the nave in order to

keep the aisles clear for the passage of the pilgrims who

wished to visit the tomb of St. Gall.

A capitulary issued by Charlemagne between 775 and 790 directed

that all children be baptized during their first year of life. Although this

law applied mainly to the newly conquered Saxon territories, it was not

likely to have been issued had it not reflected a general custom. Capitulatio

de Partibus Saxoniae, 775-790, chap. 19; ed. Boretius, Mon. Germ.

Hist., Leg. II, Cap., I, 1883, 69: "Similiter placuit his decretis inserere,

quod omnes infantes infra annum baptizantur."

Conventus episcoporum ad ripas Danubii, 796; ed. Werminghoff,

Mon. Germ. Hist., Conc., II, 1906-9, 173: "Duo tantummodo legitima

tempora, in quibus sacramenta baptismatis . . . sunt celebranda, Pascha . . .

et Pentecosten."

Hincmari Rhemensis archiepiscopi opera omnia; Migne, Patr. Lat.,

col. 773: "Et qui fontes lapideos habere nequiverit, vas conveniens ad hoc

solummodo baptizandi officium habeat."

Here reproduced by courtesy of Dr. Peter Ludwig, to whom I owe

the following information: Height, 95-96 cm.; diameter, 97.5 cm. The

walls of the font are slightly curved and slightly askew. A similar font,

from Petershausen (Cochem) is now in Feldkirchen (Neuwied). See

Kunstdenkmäler Rheinland-Pfalz, 647, fig. 489.

Although not unique; fonts are found in the same place, according

to Pudelko, 1932, 15, in the churches of Halberstadt, Gernrode, and

Magdeburg.

ALTAR OF THE SAVIOR AT THE CROSS & THE

PLACE OF WORSHIP FOR LAYMEN

The space between the second and third transverse partitions

of the nave serves as the parish church for the monastery's

serfs and tenants and as the place of worship for the

pilgrims and visitors. It contains between the sixth pair of

columns the altar of the Saviour at the Cross (altar

scī saluatoris ad crucem). This altar is surmounted by a large

86. TABRIZ, IRAN. RECONSTRUCTION AFTER PASCAL COSTE [after Saare, Denkmäler Persischer Baukunst, Berlin, 1901, 29, fig. 26]

The masjed i Kebud or Blue Mosque was built by Jehan Shah of the Kira Kuyumli dynasty (1437-1467). The mosque, now in ruins, is of a

type reaching far back to the early centuries of Mohammedism.

the hexameter:

Crux pia uita salus miseriq, redemptio mundi[39]

Pious cross: life, health, and redemption

of the wretched world

The cross rises 10 feet above the altar, and has a spread of

7½ feet. Altars in honor of the Holy Cross existed in the

abbey churches of Centula, Fulda, Corvey-on-the-Weser,

St. Vaast at Arras, the Cathedral of Le Mans, and at many

other places.[40]

As in the Church of the Plan of St. Gall,

they were located in the axis of the church at a point lying

midway between the eastern and western ends of the

church.

Willis (1848, 94) mistakenly read via instead of pia. Leclercq (in

Cabrol-Leclercq, VI:1, 1924, col. 94) copied the error.

For Centula, see Effmann, 1912, fig. 8; for Fulda, see Beumann and

Grossmann, 1949, 45, figs. 3 and 4; for Corvey-on-the-Weser, Rave,

1957, 94, fig. 83; a comprehensive treatment of the subject may be found

in the chapter "Heiligkreuzalter" in Braun, 1924, 401-406.

AMBO

The last 1½ bays of the nave are again completely

screened off by railings. In the center of this enclosure,

which is accessible by two lateral passages from the west

and a central passage from the east, there rises a circular

pulpit (ambo) on a concentric plinth 10 feet in diameter,

from which "is recited the lesson of evangelic peace" (hic

euangelacae recitat' lectio pacis).

The Plan does not tell us from what side the ambo was

entered. But since it was from here that the abbot or

visiting bishop addressed the crowd congregated around

the altar of the Holy Cross, the lectern side of the ambo

must have been at the west, the entrance side at the east.

Pulpits of this kind were in use in Early Christian churches

from the fourth century onward.[41]

They were of circular,

ovoid, or polygonal shape. A typical example from the

church of Hagia Sophia, in Salonica, now in the Museum

of Constantinople, is shown in figure 98.[42]

For early documentary sources, see the article "Ambon" by Leclercq

in Cabrol-Leclercq, I, 1907, cols. 1330-47; the article "Ambo" in

Reallexikon der Deutschen Kunstgeschichte, I, 1937, cols. 627-35.

After Orlandos, II, 1954, 546, fig. 511. For other examples, see ibid.,

544-66, and the articles cited in the preceding notes. A remarkable

medieval specimen is the ambo of Henry II in the Palace Chapel at

Aachen (Doberen, 1957, 308-59). In our reconstruction of the ambo of the

Plan of St. Gall, we have aimed at a solution that lies stylistically somewhere

between the ambo of Hagia Sophia at Salonica and the ambo of

Henry II at Aachen.

LECTERNS FOR READING

Further east of the ambo, yet within the same enclosure,

are "two lecterns for reading" (analogia duo ad legendū),

one to be used "at night" (in nocte), the other, by implication,

in the daytime. They are built against the railing that

separates the nave from the crossing and must have faced

eastward toward the place where the monks congregated.

The existence of these two lecterns suggests that the service

books which they supported were so large that they could

not be easily held in the hand. This holds true, practically

without exception, for the Carolingian Bibles and Psalters.[43]

For typical cases see Koehler, I, 1930, pl. 42-52 (Grandval Bible)

and pl. 69-89 (Vivian Bible); and Merton, 1923, pl. XXI-XXVI

(Folchart Psalter) and XXVIII-XXXII (Psalterium aureum).

II.1.7

TRANSEPT

The transept (fig. 99) is separated from nave and aisles by

screens that run across the entire width of the Church. It is

also divided internally into separate compartments by

means of longitudinal screens that separate the crossing

from the transept arms, and within the latter there is a

further separation of the areas reserved for the monks from

the crypt. The monks and priests who seek access to the

crossing and to the presbytery must cross these passages.

The layout of the transept and the choir that adjoins it

in the east is complex and, sometime after the Plan was

drawn, someone—perhaps the author of the Plan himself—

considered it desirable that the boundaries of the constituent

spaces of this part of the Church be made more conspicuous.

He put them into visual prominence by redrawing

them in a dark brown ink, thus distinguishing the principal

architectural partitions from the furnishings shown in the

interior of these spaces. In consequence all the transept

walls, as well as the boundary lines between the crossing

and the transept arms, as well as the two lateral walls of the

presbytery, were rendered twice, first in red, and subsequently

in brown ink.

THE CROSSING SQUARE AND ITS FURNISHINGS

The crossing is the "choir for the psalmodists" (chorus

psallentium). It is furnished with four "benches" (formulae).

Schmidt's interpretation of formulae as lecterns (Pulte)

appears to me untenable. In the ninth century only the

directing monk held an antiphonary in his hands; and this

was too small to require even one lectern,[44]

let alone four

of the size of the formulae on the Plan of St. Gall which are

10 feet long and at least 2½, probably 3¾, feet wide.

Moreover, the scribe's term for "lectern" is not formula but

analogium and in the three places where lecterns are shown

on the Plan, they are rendered either as simple squares (the

two lecterns by the rail that separates the crossing from the

nave of the Church; see end of preceding paragraph) or as

a square with a circle inscribed (the Reader's lectern in the

Refectory; see below, p. 268f). Formula, a diminutive of

forma[45]

(used in the same sense) is the common medieval

designation for "bench" or "choirstall" as well as for those

wooden supports that are used for kneeling in prayer (prieDieu—kneeling

chair—Betstuhl) or to be leaned upon in the

act of inclination (hence also called inclinatoria) to preclude

excessive physical strain during the long hours of religious

devotion, a problem that had been of considerable concern

to the fathers of early monasticism.[46]

In the choir stalls of

later monastic churches (and to an even higher degree the

large cathedral churches) both of these appurtenances are

combined into a single piece of furniture, consisting of a

wooden range of seats with panelled lean-to's in the back

and a solid range of supports for kneeling and prayer in

front.[47]

The formulae in the crossing of the Church of the

Plan may have been an early variant of this type of seat. In

their simplest form, one might imagine them to have looked

like the church bench from Alpirsbach (fig. 100) with

supports for kneeling and bending either physically

attached to them or placed separately in front of them. The

reader may have observed that the formulae of the crossing

are a little wider than the corresponding benches in the two

transept arms (also called formulae). The latter have the

standard width of 2½ feet used by the designer for benches

wherever they appear on the Plan. The former look as

though they were meant to be 3¾ feet wide (1½ standard

modules). I think that this distinction is intentional, i.e.,

that the designer used this variation in size to emphasize the

greater liturgical importance of the formulae of the crossing

square.[48]

In two essays published in 1965 and 1967/68[49]

Father

Corbinian Gindele expressed the view that the location of

the formulae in the crossing square (all at right angles to the

longitudinal axis of the Church) indicates that the entire

choir of monks when seated faced the altar in an easterly

direction (versus or contra altare) in compliance with a

custom which he claims was common in Early Christian

times, rather than facing each other transversely across the

altar from two opposite rows of seats ranged longitudinally

along the walls of the altar space, as became the rule in later

Cluniac monasteries. This is incorrect visual exegesis. The

four formulae in the crossing square when fully occupied

could seat no more than four monks each, altogether sixteen

(counting as normal requirement a sitting area 2½ feet

square per person). The full contingent of monks attending

88. ALTAR OF MITHRAS. WIESBADEN,

ALTERTUMSMUSEUM

FROM THE MITHRAS SANCTUARY, HEDDERNHEIM

[photo: Horn]

The six- or eight-lobed rosette (a misnomer, since it is by origin a

symbol of stellar, not chthonic forces) appears in Near Eastern

imagery as an attribute of gods and royalty from the 3rd millennium

onward. It became associated with Mithras after his cult was

established in the Euphrates Valley. It spread westward into Rome

as Rome increased its hold on Asia, finding a stronghold in the army

among tradesmen and slaves, mainly Asiatics. Christian antagonism

to Mithraism prevented the rosette from becoming one of Christ's

personal attributes along with the halo, globe, and canopy

(cf. figs. 102-103), all of which Christ inherited from pagan deities.

Despite official antagonism, the rosette was nevertheless widely

diffused in the Christian communities of Syria and North Africa and

with fervor adopted by the Germanic invaders of Rome.

89. MORTUARY LANTERN

Pers, deux-sevres, france

[Archives photographiques d'art et d'histoire:

Monuments historiques, Sept. 1890]

"Lanterns of the Dead" are tall, hollow columns of stone, often of

considerable height, with entrances at the bottom and small pavilions

at the top, where the light of a lamp during the night signaled

existence of a cemetery or seigneurial tomb. The specimen here shown

is one of the finest of its kind.

p. 342). These could not under any circumstances have

been accommodated by the four free-standing benches of

the crossing square. The Plan shows with unequivocal

clarity where the main body of monks was seated: on the

long bench that runs along the walls of the presbytery and

through the round of the apse, as well as on supplementary

benches ranged along the walls of the two transept arms.

If in the course of the development that led from Early

Christian to medieval monasticism, the seats of the monks

were shifted from an eastward-facing position to one in

which the monks faced each other transversely from either

side of the altar, this shift must have been undertaken before

the Plan of St. Gall was drawn. The seating arrangement

for the monks shown on the Plan of St. Gall, however, in

fact follows a pattern that had already been firmly established

for the bishop and the secular clergy in the days of

Constantine the Great (fig. 104) and in the course of the

fifth and sixth centuries become standard for the great

episcopal churches, both in the eastern and western part of

the empire.[51]

The four free-standing benches in the crossing square

must have had a function distinct from that of the wall

benches in the presbytery, the apse and the transept arms.

I am inclined to assume (accepting a suggestion made by

my colleague, Richard L. Crocker) that they served as seats

for the specially trained singers who chanted the more

difficult sequences of the psalms in alternation with the

regular monks. A magnificent twelfth-century example of

the type of bench we might expect to have found in the

crossing of the Church of the Plan is shown in figure 100.[52]

On the eastern side of the crossing, two flights of stairs

of "seven steps" (septem gradus, similit) lead up into the

fore choir. Halfway up these steps, against the crossing

piers, there is, to the left, the "altar of St. Benedict" (altar̄

sc̄ī benedicti), to the right, the "altar of St. Columban"

(altar̄ scī colūbani).

The presence of the altars of St. Benedict and St.

Columban in such a prominent place is not surprising.

They are the representatives of the two great monastic

traditions, the Irish and the Benedictine, which shaped the

history of the monastery of St. Gall.[53]

Schmidt, 1956, 372. That Carolingian antiphonaries were of small

size was pointed out to me by my colleague Richard L. Crocker. Johannes

Duft, in a personal note addressed to me on 21 July 1967, writes: "My

knowledge of the antiphonaries of the 9th, 10th and 11th centuries fully

confirms this view. They are small books, held in the hands of the monks

who conducted the liturgical songs."

On early monastic attitudes concerning the need for alleviation of

devotional strain (onus, labor) through diversity (diversitas) and physical

relaxation (relevatio) with the goal of attaining spiritual delight and

refreshment (delectatio), see the interesting study of Gindele, 1966,

321-26.

For good examples see Viollet-le-Duc, Dictionnaire Raisonné, VIII

(Paris, n.d.), 461ff, s.v. "Stalle"; Loose, 1931, passim and Ganz-Seeger,

1946, passim.

See the remarks made above, p. 95, on the occasional use of a

submodule of 1¼ feet by the designer of the Plan, besides the standard

module of 2½ feet.

From the Church of Alpirsbach (Black Forest); destroyed during

World War II; see Müller-Christensen, 1950, 11, figs. 2 and 3; and

Falke, 1924, pl. 1.

Cf. Poeschel, 1956, 138; and Müller, in Studien, 1962, 141-45. In

the Abbey Church of St. Riquier, the altars of St. John and St. Martin

were in exactly corresponding positions; see Effmann, 1912, fig. 8.

SOUTHERN TRANSEPT ARM

In the southern transept arm, against the east wall on a

platform raised by two steps (gradus), is the "altar of St.

Andrew" (alt̄ scī andreae). It is a little larger than the altars

in the aisles of the Church, but smaller than the altars of

St. Paul and St. Peter in the apses. The three remaining

walls of this transept arm are lined with benches providing

sitting space for twenty monks. A freestanding bench

(formula) in the center of the floor can accommodate five

more monks. Like the corresponding benches in the crossing,

this bench must have been reserved for the trained

singers. The layout suggests that in such cases where

professional celebrations required that the full choir of

monks be split into smaller segments officiating simultaneously

in different parts of the Church, each transept

arm was so laid out as to be capable of serving as a liturgically

autonomous station.

The southern transept arm has entrances which make it

possible for the monks to enter it directly from the Dormitory

for night services (Matins) and at daybreak (Lauds),

and from the northeastern corner of the Cloister for the day

offices. A door in the east gives access to the Sacristy. From

the Dormitory the southern transept arm could only be

reached by a "night" stairway. The draftsman does not

tell us anything about the course or the landing of this

stairway, but stairways just like this exist in the corresponding

places in the abbey churches of Fontenay (Côted'Or)

and Noirlac (Cher), France, and in the Priory

Church of Hexham (Northumberland), England (fig. 101).[54]

The traces of others, not quite as well preserved, may be

found in the abbeys of Tintern (Monmouthshire),

Beaulieu (Hampshire), Hayles (Gloucestershire), and at

St. Augustine's in Bristol.[55]

For Fontenay and Noirlac, see Aubert, I, 1947, 304, fig. 220, and

303, fig. 218; for Hexham, see Hodges, 1913; Cook, 1961, 66 and pl.

VIII; Cook-Smith, 1960, fig. 39.

For Tintern Abbey, see Brakspear, 1936, 9 and plan; for Beaulieu

Abbey, see Fowler, 1911, 71 and pl. XXVI, and VHC, Hampshire, IV,

1911, plan facing 652; for Hayles Abbey, see Brakspear, 1901, 126-35;

for St. Augustine's in Bristol, see Cook, 1961, 66 and pl. IX.

NORTHERN TRANSEPT ARM

The layout of the northern transept arm is identical with

that of its southern counterpart. Its altar is dedicated

jointly to SS. Philip and James (alt̄ scī philippi et iacobi). A

door in the north wall communicates with the Abbot's

House, another one in the east wall leads into the Scriptorium.

II.1.8

PRESBYTERY

HIGH ALTAR: ST. MARY AND ST. GALL

Raised as it is by seven steps above the level of the transept,

the presbytery with its high altar dominates the entire

Church. The liturgical pre-eminence of this part of the

building is emphasized by a hexameter in capitalis rustica:

SC̄A SUPER CRPTĀ SC̄ŌRUM

STRUCTA NITEBUNT

ABOVE THE CRYPT THE

HOLY STRUCTURES OF THE SAINTS

SHALL SHINE.

The "holy structures" are the high altar of the Church,

dedicated jointly to St. Mary and St. Gall (altare sc̄ē mariae &

scī galli) and the tomb of the holy body (sacrophagū scī

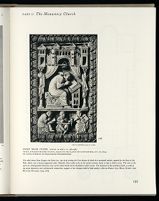

89. MEROVINGIAN CARVED STONE

POITIERS, MUSÉE DU BAPTISTÈRE, FRANCE

[photo: Photomecaniques]

The stone may have come from the

church of Notre-Dame l'Ancienne.

90. MARBLE SLAB WITH CROSS

& SIX-LOBED ROSETTES (8TH CENT.)

LUCCA, MUSED DI VILLA GRININI

Associated with the cross, as in many

Syrian, North African and Visigothic slabs

of earlier periods, the six-lobed rosette

probably retained its original meaning as a

symbol of light overcoming evil forces allied

with darkness. In the Middle Ages the

symbol went underground.

[after Arte Lombarda, suppl. vol. 9:1]

92. HEX SIGNS

On Pennsylvania Dutch barns, they often are several feet in diameter

[after Sloane, 1954, 67]

91. SIX-LOBED ROSETTE IN MASONRY OF

MONASTIC BARN (1211-1227) PARCAY-MESLAY, FRANCE

[photo: Horn]

The rosette was cut into masonry or timber work of many medieval

tithe barns as a spell to ward off harm to livestock or harvest.

the altar.

The joint patrocinium of Mary and St. Gall has its

explanation in the fact that Mary was the patron of the

original oratory of St. Gall. The deeds of the Monastery

disclose how in the course of the eighth century the name

of St. Gall began to be associated with that of Mary with

increasing frequency until it eventually replaced it entirely

and became the local place name (coenobium sancti Galli, or

sancti Galloni).[56]

The altar is raised on a plinth, a distinction

not accorded any other altars in the Church. We must

expect it to have been surmounted by a canopy. A capitulary

issued by Charlemagne in 789 directs that altars should

be surmounted by such superstructures (Ut super altaria

teguria fiant vel laquearia).[57]

An ancient symbol of the

celestial dome and hence, by implication, of universal

rulership, this motif had been transmitted from the Roman

rank of the gods (fig. 102.B),[60] and from the emperor to Christ

as Christ acquired the status of a Roman state god. It was

no lesser person than Constantine the Great who set a

conspicuous precedent for this transmission of celestial

prerogatives to the new God of Heaven when he adorned the

high altar of the latter's prime apostle with a pedimented

canopy richly revetted with silver and gold, in the Church

of St. Peter's in Rome (fig. 104).[61]

Duplex legationis edictum, May 23, 789, chap. 33; ed. Boretius,

Mon. Germ. Hist., Leg. II, Cap., I, 1883, 64. Considering the vast

number of altars with which churches were equipped during this period,

it is possible that the law applied only to the high altar.

WALL BENCHES

Wall benches lined both sides of the fore choir and

continued into the round of the apse. The monks faced

each other vultus contra vultum from either side of the

altar, except for those who sat in the curving parts of the

apse, and faced the altar westward. The abbot presumably

sat at the apex of the apse and had a counterpart in the

choir master, who occupied a position of comparable

centrality in the middle of the crossing square. The layout

of the benches discloses that crossing and presbytery—

despite their different levels—formed liturgically a unitary

space; and a count of the sitting places available for the

monks in the areas screened off for their exclusive use in the

eastern parts of the Church suggests that when the entire

community participated at a common service, even the

benches in the transept arms were occupied by monks

attending the service,[62]

. On the north side "an upper

entrance leads into the library above the crypt" (introitus

in bibliothecā sup criptā superius). The qualifying adjective

"upper" implies the existence of a "lower" entrance, which

must have made the library accessible from the Scriptorium

below it. The prototype for the raised platform of the

presbytery and the apse of the Church of the Plan of St. Gall

was the raised presbytery that Pope Gregory the Great had

installed in Old St. Peter's in Rome between 594 and 604

(fig. 104) by lifting the pavement of the new choir 5 feet

above the original floor of the church and establishing

below this platform a crypt that incorporated directly

beneath the new altar the old shrine of St. Peter, which

before this alteration had been exposed to view.[63]

TOMB OF ST. GALL AND ITS RELATION

TO THE CRYPT

There has been considerable discussion on whether the

tomb of St. Gall should be interpreted as standing in the

presbytery above, or in the crypt below it; and whether, if in

the crypt, it should be thought of as standing behind or

underneath the altar.[64]

It should be remarked that on the

Plan the tomb is entered on the east side of the altar, and

that the plurality of "holy structures" referred to in the

affixed hexameter as "shining above the crypt" should

lead one to think that the sarcophagus stood in the upper

sanctuary.

Despite these facts, it has generally been assumed that

the tomb of St. Gall was meant to stand in the crypt underneath

the presbytery, and for good reason, since it was the

desire to find appropriate protection for the relics, in the

first place, that had led to the invention of crypts. The

proper solution to this puzzle may have been found by

Willis when he speculated, "It is not impossible that

although the real sepulchre of the saint was in the confessionary

or crypt below, a monument to his honour may

have been erected above the altar."[65]

That such a double-storied

structure actually existed in St. Gall is suggested by

two tales reported in the Miracles of St. Gall. One of these

tales speaks of a cripple who was taken by his friends to the

memoriam B. Galli and daily "laid close to the sepulcher in

the crypt" (cottidie juxta sepulchrum in crypta collocatus).

Another tale mentions "a lamp which burned nightly

before the upper altar and tomb and which also threw some

light through a small window upon the altar of the crypt"

(lumen quod ante superius altare et tumbam ardebat per

quandam fenestrum radios suos ad altare infra cryptam

positum dirigebat).[66]

Some further information concerning

the topographical relation of tomb and altar at St. Gall can

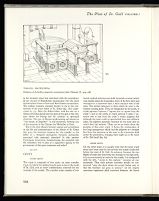

93. PLAN OF ST. GALL. NAVE AND AISLES OF CHURCH

In the axis of the nave, west to east: baptismal font, altar of SS John the Baptist and John the Evangelist, altar of the Saviour at the Holy

Cross, ambo; and midway between the two latter, two crucial inscriptions designating the nave as 40 feet wide, and each aisle, 20 feet wide.

In the north aisle, west to east: altars of SS Lucia and Cecilia, The Holy Innocents, SS Martin and Stephen. In the south aisle: SS Agatha and

Agnes, St. Sebastian, SS Mauritius and Lawrence.

work informs us that on his death at Arbon, October 16,

about the year 646, the body of the Saint was taken to his

oratory at St. Gall and buried in a grave dug between the

altar and the wall.[67] Forty years later, his sepulcher was

violated by plunderers who mistook the coffin for a treasure

chest, but Boso, Bishop of Constance, replaced the coffin

"housing the relics of the sacred body, in a worthy sarcophagus

between the altar and the wall, erecting over it a

memorial structure congruent with the merits of the God-chosen."[68]

The chronicles of St. Gall report no further

translation of the Saint, and from this fact, as Willis concluded

correctly, it has to be inferred that the location of

the tomb remained the same, even in Gozbert's church.[69]

Nowhere in any contemporary allusions to the sepulcher of

the Saint, is the tomb reported to stand underneath the altar.

For the latest discussion, see Reinhardt, 1952, 20, where the tomb is

reconstructed standing directly beneath the altar.

Willis, loc. cit. The Life and Miracles of St. Gall was written by an

anonymous monk of St. Gall during the last third of the eighth century.

At the request of Abbot Gozbert (816-837) this work was re-edited in

833-34 by Walahfrid Strabo, who incorporated into his edition a continuation

of the account of the miracles which had been written by the

Monk Gozbertus, a nephew of Abbot Gozbert. Best edition: Vita Galli

confessoris triplex, ed. Bruno Krusch, Mon. Germ. Hist., Script. rer.

merov., IV, Hannover, 1902, 229-337. The miracles to which Willis

refers belong to the part that was written by the Monk Gozbertus. See

"Vita Galli auctore Walahfrido," Liber II, chaps. 31 and 24, ed. Krusch,

1902, 331 and 328-29.

"Sepulchrum deinceps inter aram et parietem peractum est, ac melodiis

caelestibus resonantibus corpus terrae conditum." See "Vita Galli auctore

Wettino," Liber II, chap. 32, ed. Krusch, 1902, 275.

"His aliisque exortationibus finitis, sancti corporis globa in sarcofago

digno inter aram et parietem sepulturae tradebatur, atque super illud

memoria meritis electi Dei congruens aedificabatur." See "Vita Galli

auctore Wettino," Liber II, chap. 36, ed. Krusch, 1902, 277.

II.1.9

EASTERN APSE

ALTAR OF ST. PAUL

The eastern apse (exedra) houses the altar of St. Paul,

which is designated with the hexameter:

Hic pauli dignos magni celebramus honores

Here we celebrate the honors worthy of

the great St. Paul

It has been argued that St. Paul was given this prominent

position in the Church of St. Gall because he was the

patron saint of an earlier church torn down in 830 to make

room for Abbot Gozbert's new building. This contention

has no base in fact. In the entire historical tradition of the

Abbey of St. Gall there is no source that would attest the

existence of a sanctuary dedicated to St. Paul.[70]

That a previous church was dedicated to St. Paul was first claimed

by Keller, 1844, 9 and subsequently taken over by Braun, 1924, 389. The

theory was refuted by Hecht in 1928, 14-15; Boeckelman, 1956, 137 and,

Poeschel, 1961, 19.

SYNTHRONON

The apse has the full width of the fore choir and is

furnished in its entire circumference with a wall bench that

continues the course of the fore choir benches. Together,

this range of benches offers sitting space for forty-eight

monks and the abbot. Its curved portion in the apse is

broader than the two straight arms in the presbytery. The

latter are 2½ feet wide (1 standard module); whereas the

former look as though they were meant to have a width of

3¾ feet (1½ standard modules). Again I think that this dimensional

differentiation is deliberate and that the designer

used it to stress the hierarchical prominence of that portion

of the bench on which the abbot and the senior monks

were seated, thus distinguishing it from the seats where

monks of lesser status were placed westward in sequence of

decreasing seniority. The designer had used the same

device in stressing the greater liturgical significance of the

benches for the specially trained singers (formulae) in the

crossing square in relation to those located in the transept

arms.

To seat the highest dignitaries of the ecclesiastical

community on a semicircular bench raised against the wall

of the apse (synthronon) is not a monastic invention, but a

transference to monastic ritual of a custom established in

the secular church. In Palestine this arrangement is

attested, as early as 314 A.D., for the basilica of Tyre

(fig. 104), built by Bishop Paulinus (known through an

unusually accurate and detailed description by Eusebius)

and such later fourth-century buildings as the Constantinian

Nativity Church in Bethlehem (333 A.D.), the

basilica of Emmaus (first half of the fourth century), the

cathedral of Gerasa (third quarter of the fourth century),

and the Church of the Multiplication of the Bread at

et-Tabgha (end of the fourth century). Toward the turn of

the same century it also appears at the coast of Istria in the

so-called Chiesetta at Grado and Santa Maria delle Grazie

at Grado. By the middle of the fifth century the layout is

standard in most Near-Eastern countries, and above all in

Greece. Frequently the semicircular benches in the apse

are prolonged by two straight arms reaching westward into

the bema. Good examples of this arrangement are the

basilica of Thasos (figs. 94 and 144) and the magnificent

church of Corinth-Lechaion (fig. 161). The Constantinian

basilicas of Rome do not appear to have been provided with

this type of bench for Bishop and clergy—unless they

were built in wood, leaving no traces for posterity—but

toward the end of the sixth century a synthronon of

impressive monumentality was set up by Pope Gregory the

Great in the apse of the most venerable church of western

Christendom, Old St. Peter's (fig. 103) forming a sight of

inescapable impressiveness to every transalpine visitor of

Rome, layman or clergyman, and inter alia the physical

stage for Charlemagne's coronation on Christmas day of

the year 800.[71]

At what time precisely this seating arrangement was

adopted by the monks is an unsolved historical problem.

But it is not unreasonable to conjecture that its acceptance

94. THASOS, MACEDONIA

Presbytery of the basilica, perspective reconstruction [after Orlandos, II, 1954, 528]

(if not victory) of Benedictine monasticism over the more

individualistic forms of Irish and Near-Eastern monachism.

The earliest monastic example known to me is the synthronon

of the royal abbey of St. Denis (fig. 167) consecrated

in 775. Here the Abbot-father took his seat on a

throne of bronze placed into the apex of the apse at the very

spot where the bishop had his cathedra in episcopal

churches. The seat, of Roman workmanship and known as

"the throne of Dagobert" is still preserved, forming one

of the treasures of the Cabinet des Médailles in Paris.

Was it the close alliance between regnum and sacerdotium

in the life and administration of the Abbey of St. Denis

that gave the historical impetus for the transfer to the

abbot of a liturgical prerogative formerly exclusively

associated with episcopal churches? Is this another

Carolingian innovation, foreshadowing the powerful role

the monastery was to play as a supportive agency in the

government of this great statesman and ruler?

On the archaeology and history of the synthronon in Greece and

the Near East see Soteriou, 1931, passim; Orlandos, 1952, 489ff; Hodinott,

1963, passim; Kraeling, 1938, passim, and Crowfoot, 1941, passim. For

examples along the Adriatic coast see Egger, 1916, 29ff and 130 and

Brusin-Zovatto, 1957, 419ff. All of this and much additional material is

now conveniently compiled in Nussbaum's exhaustive study of 1965,

with full bibliographical references to previous literature.

On the reconstruction of the basilica of Tyre see Nussbaum, op. cit.,

64-66 and the literature there cited; and for the description by Eusebius,

on which this reconstruction is based: Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History,

ed. Lake, II, 1932, 426-27; ed. Williamson, 1965, 394.

II.1.10

CRYPT

OUTER CRYPT

The crypt is composed of two parts: an outer corridor

crypt, by which the visiting laymen gain access to the tomb

of St. Gall, and an inner confessionary, reserved for the

worship of the monks. The corridor crypt consists of two

barrel-vaulted subterranean shafts (inuolutio arcuum) which

run outside along the foundation walls of the fore choir and

terminate in a transverse shaft a short distance west of the

apse. The arched entrances to these shafts lie next to the

eastern crossing piers. They are designated in the south, in

criptā ingressus ʈ egressus ("ingress into or egress from the

crypt") and in the north, in criptā introitus ʈ exitus ("entrance

into or exit from the crypt") which suggests that

although the tomb could be approached from two different

sides, the pilgrims generally returned on the same side on

which they had entered. There can be no doubt about the

purpose of this outer crypt. It forms the continuation of

two long passageways which lead the pilgrims in a straight

line from the entrances in the west to the transverse shaft

under the presbytery, bringing them right up to the tomb

of St. Gall itself (fig. 82).

INNER CRYPT

On the other hand, it is equally clear that the inner crypt

must have been used for the services the monks conducted

before the tomb of St. Gall. Its entrance, between the two

flights of stairs that lead from the crossing to the high altar,

is in an area entirely set aside for the monks. It is designated

with the title, "access to the confessio" (accessus ad confessionem).

That such private oratories should be constructed

"near the place where the sacred bodies rest, so

that the brothers can pray in secrecy" (ut ubi corpora

sanctorum requiescunt aliud oratorium habeatur, ubi fratres

capitulary issued in 789.[72]

Duplex legationis edictum, May 23, 789, chap. 7; ed. Boretius, Mon.

Germ. Hist., Leg. II, Capit., I, 1883, 63.

II.1.11

SACRISTY AND VESTRY

In the corner between the fore choir and the southern

transept arm, and directly attached to them, there is a

double-storied structure, 40 feet square, which contains

"below, the Sacristy, above, the repository for the church

vestments" (subtus sacratorium, supra uestiū ecʈae repositio).

The Plan gives the layout of the Sacristy. In the center a

large square table for the sacred vessels (mensa scōr̄ uasorum)

is raised on a plinth. Benches and a chest or table are set

against the walls, and the room is heated by a corner fireplace.

The Plan does not disclose the location of any stairs

connecting the Sacristy with the Vestry, but it is reasonable

to assume that they were located above the arm of the

corridor crypt that lies beneath the Sacristy.[73]

The custodianship of Sacristy and Vestry was the

responsibility of the Sacrist (custos ecclesiae)[74]

who also was

in charge of the preparation of the host and the holy oil.

This task was performed in a separate building, as the title

indicates: the building where the holy bread is baked

and where the oil is pressed (domus ad pparandū panē scm̄ &

oleum exprimendum.); this building measures 22½ × 37½

feet and is connected to the Sacristy by a covered passageway

that is bent twice at right angles. The room contains

a press, a table, and an oven as well as benches all along

the remaining parts of its walls.

II.1.12

SCRIPTORIUM AND LIBRARY

Nec non sanctorum dicta sacrata patrum;

Hic interserere caveant sua frivola verbis,

Frivola nec propter erret et ipsa manus,

Correctosque sibi quaerant studiose libellos,

Tramite quo recto penna volantis eat.

Per cola distinguant proprios et commata sensus,

Et punctos ponant ordine quosque suo

Ne vel false legat, taceat vel forte repente

Ante pios fratres lector in ecclesia.

Est opus egregium sacros iam scribere libros,

Nec mercede sua scriptor et ipse caret.

Fodere quam vites melius est scribere libros,

Ille suo ventri serviet, iste animae.

Vel nova vel vetera poterit proferre magister

Plurima, quisque legit dicta sacrata patrum.

Together with the inspired Fathers' gloss.

Here let no empty words of writers' own creep in—

Empty, as well, when hand or eye betray.

By might and main they try for wholly perfect texts

With flying pen along the straight-ruled line.

Per cola et commata[75] should make clear the sense

To prevent the lector, before reverend monks in church,

From reading false, or stumblingly, or fast.

Our greatest need these days is copying sacred books;

Hence every scribe will thereby gain his meed.

To copy books is better than to ditch the vines:

The second serves the belly, but the first the mind.

The master—whoe'er transmits the holy Fathers' words—

Needs wealthy stores to bring forth new and old.[76]

On the Scribes by Charles W. Jones.[77]

Alcuin's poem On the Scribes offers a metrical inscription

intended to decorate the entrance of a monastic scriptorium,

perhaps the scriptorium of the Monastery of St. Martin's

at Tours.[78]

95. LUTTRELL PSALTER, LONDON, BRITISH MUSEUM. Add. Ms. 42130, fol. 37

Baptismal scene [by courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum]

97. AACHEN, COLLECTION DR. PETER LUDWIG

Baptismal font, around 1100

96. DEERHURST, GLOUCESTERSHIRE, ENGLAND

Priory church, Saxon baptismal font

LAYOUT

On the northern side of the Church of the Plan, in a

position corresponding exactly to that of the Sacristy and

Vestry, there is a double-storied structure of like design,

which contains "below, the seats for the scribes, and above,

the library" (infra sedes scribentiū, supra bibliotheca). From

a purely functional point of view the location of these two

important cultural facilities is ideal. Their situation at the

northeast corner of the church, in the shadow cast by

transept and choir, protected the scribes from the glare of

the sun as it travelled through the southern and western

portion of its trajectory and allowed them to work in the

more diffused light made available by their east and north

exposure.

The Scriptorium is accessible by a door from the northern