In June 1739, in order to secure evidence for an action of libel,

agents of the Walpole ministry raided the offices of the printer and editor

of the Opposition organ, Common Sense, and seized their

papers. Of these, 218 autograph items, the great majority representing copy

for the printer, are preserved together at the Public Record Office

(Chancery Lane)—call number: SP9/35. Since this collection by no

means comprises a complete run of the printer's copy to the time of

seizure, and since—no doubt for prudential reasons—none of

the copy

is signed, scholars will find this material of limited use in identifying

contributors, though, by a comparative analysis of the handwriting, it is a

simple matter to distinguish, in a general way, articles written by the editor

from those submitted by occasional correspondents to the journal.

Included among these papers, however, is at least one item of

exceptional interest; for here, in the form of a pseudonymous letter to the

editor recommending silence as "the utmost Perfection of human Wisdom,"

is the only extant literary prose manuscript by Henry Fielding. Signed

"Mum Budget" and dated from Devon on April Fool's Day 1738, this witty

piece, though published in Common Sense on 13 May, has

never been attributed to Fielding. It is valuable, however, not only as an

important addition to the canon, representing one of Fielding's earliest

known publications as a periodical essayist, the form in which—as

editor

of The Champion (1739-41), The True Patriot

(1745-46), The Jacobite's Journal (1747-48), and The

Covent-Garden Journal (1752)—he would soon outshine every

rival

for a decade. What is more, appearing in the midst of the

two-and-a-half-year interval between the passage of the Theatrical Licensing

Act (June 1737), which put an

end to his career as a dramatist, and the publication of The

Champion (November 1739), when he emerged as principal

journalist

for the Opposition, the essay sheds light on Fielding's personal

circumstances and political relationships in one of the most obscure periods

of his life. Because

literary manuscripts by Fielding are so rare

[1] —and because this, indeed,

is the only

one extant which he intended as printer's copy—I will reproduce it

here

photographically, as well as supplying an annotated transcript for more

convenient reference. Fully to appreciate its implications, both political and

biographical, we need first, however, to review the circumstances in which

Fielding wrote it.

Sponsored by his friends in Opposition, Common Sense: or,

The

Englishman's Journal began publication on 5 February 1737, during

Fielding's final season as manager of the Little Theatre in the Haymarket.

In a month's time, with the production of The Historical

Register, he would cap the brilliant success of Pasquin

a

year earlier—a triumph no less spectacular than it was disastrous in

its

consequences for his career as a playwright; for, though Fielding's satire

in these plays spared neither party, it linked him in the public mind with the

Opposition's cause and moved the Ministry to silence him. As one

ministerial writer was well assured, Fielding's success with

Pasquin had caused him to be "secretly buoy'd

up,

by some of the greatest Wits and finest

Gentlemen

of the Age"[2] —among them,

surely, Lyttelton and Chesterfield, who had now initiated the new journal.

Its editor and principal writer,

however, was the Irishman, Charles Molloy (d. 1767), himself a comic

dramatist manqué and, as the former author of

Fog's

Weekly Journal (1728-37), a journalist well skilled in the art of

making ministerial politicians die sweetly in print. Its printer was the

inflexible Tory, John Purser.

In a sense Fielding, too, was associated with this paper from the start;

for its title had been borrowed from the "emblematical" figure whose

"Tragedy" is rehearsed, to hilarious effect, in the final acts of

Pasquin. Though in Pasquin Common Sense

suffered what might seem her inevitable fate in the age of Walpole, in the

pages of Molloy's weekly paper, presumably, she would live on, with due

acknowledgments to Fielding, who understood her best: "An ingenious

Dramatick Author," we are reminded in the first issue, "has consider'd

Common Sense as so extraordinary a Thing, that he has lately, with great

Wit and Humour, not only personified it, but dignified it too with the Title

of a Queen . . . ." A few months later, when Fielding needed

a "Vehicle" by which to answer a ministerial attack against the alleged

licentiousness of his political satire in The Historical Register,

it was, predictably, Molloy

who provided it.

[3] As C. W. Nichols

saw some time ago, the letter signed "Pasquin" published in

Common

Sense for 21 May 1737 is certainly by Fielding, an attribution

Molloy

himself confirms, albeit obliquely, in his leader of 21 October 1738.

[4] That Fielding, especially after the

Licensing Act had put a stop to his play writing, might contribute other

pieces to his friends' journal has always seemed likely. W. L. Cross, for

instance, wished to assign to him a pair of essays treating affectation as the

source of ridicule, which were published in

Common Sense

(3,

10 September 1737); and a recent anthologist of Fielding's criticism has

considered Cross's suggestion plausible enough to justify reprinting

them.

[5] But these essays, though the

opening of the first does bear some resemblance to Fielding's definition of

"the true Ridiculous" in the Preface to

Joseph Andrews

(1742), are stylistically quite different from his usual manner; and unlike

his known contributions to the journal, they take the form of leaders, not

pseudonymous letters to the editor—a circumstance suggesting that

they

are by someone (Chesterfield is the usual candidate) whose connection with

the paper was closer and more regular than Fielding's. Unfortunately, the

manuscripts of these essays, which would settle such speculation, have not

survived; but Cross's reasons for attributing them to Fielding are not

persuasive.

We may take it as certain, I believe, that after the "Pasquin" letter

almost precisely a year went by before Fielding made his next appearance

in Common Sense, this time as that wonderfully garrulous

advocate of the wisdom of holding one's tongue, "Mum Budget." The essay

begins, accordingly, with his anticipating the editor's surprise "at not

hearing from me in so long time." Besides making an amusing addition to

the canon, this piece is of considerable interest biographically, for what it

reveals both of Fielding's own sense of the events that precipitated the

Licensing Act, and of his hardening attitude toward Sir Robert Walpole,

whose patronage he once had courted.

[6] Indeed, to those who care about

the kind

of man Fielding was, one of the essay's special pleasures derives from its

tone: that he could make a joke of the hard blow the minister had dealt

him—by thus writing a witty

tour de force on the

wisdom of

keeping one's mouth shut in Walpole's England—is part of what one

finds so admirable in his character. For, as is evident here for the first

time, Fielding was himself convinced that, whatever may have been its

general utility to the government, the Licensing Act had been pushed

through Parliament specifically to muzzle him, and that, whatever other

plays may have

annoyed the prime minister, it was the satiric characterization of him as

Quidam in

The Historical Register which proved to be the

last

offending straw. After a long and humorous preamble, the essay from this

point takes the political turn for which, no doubt, it was chiefly written.

The yarn about the whimsical "Coffee House Politician" who was so fond

of silence that he bribed others "to hold their Tongue" and who by such

means became "the Oracle of the House" is, of course, a transparent

allegory of Walpole. The old gentleman's habit of urging "weighty Motions

concerning Tobacco, Coffee,

&c." recalls the prime

minister's unpopular Excise Scheme of 1733,

[7] as his way of fainting "at the

Sound of a

Musquet" ridicules his pacific policies toward Spain at a time when

"

Spanish Depradations" against English ships were a constant

theme of the Opposition press and in March 1738 the burden of petitions

presented to Parliament by

aggrieved merchants.

[8] His droll

indulgence of the inane and loquacious waiter, "

young Will,"

is a hit, surely, at Walpole's "creature," Sir William Yonge (1693-1755),

no less "notorious a Babbler" in "the House," who at the time was

consolidating his reputation for meaningless eloquence in speeches

supporting the minister's foreign policy.

[9] Clearly, however even-handed

Fielding

had earlier tried to be

in his political satires, he was ready now to take sides against Walpole and

his ministry. This essay is his first in a vein that, late in the following year,

would become familiar to readers of

The Champion.

The discovery of this manuscript, of course, makes the possibility all

the more attractive that Fielding made other contributions to

Common

Sense during the eighteen months that would pass before he

launched

his own paper in behalf of the Opposition. Textually, the relationship

between the manuscript and the two printed versions of the

essay—that

of the original issue of Common Sense (13 May 1738) and

that

appearing in the two-volume reprint (1738-39)—reveals, however,

certain

peculiarities which complicate the problem of identifying Fielding's hand

elsewhere in the journal. Most significant of these is the fact that, in setting

the article, the compositor systematically, and without editorial authority,

altered a characteristic of Fielding's style which has long served as an

indispensable test for anyone proposing additions to the canon: in every

instance Fielding's favorite archaism, the use of hath for

has, has been modernized. And presumably

his doth's would have been similarly treated if he had had

occasion to use that verb in the essay. To compound the problem, it is clear

that this particular sophistication was not a feature of Purser's "house

style": the printed versions of the "Pasquin" letter retain Fielding's

characteristic usage. Indeed, Molloy himself often (though not invariably)

prefers the same archaisms. These changes from the manuscript, therefore,

would seem to be an expression of the stylistic taste of a particular

compositor—who, since he was no doubt employed at other times by

Purser, may be supposed to have treated other essays in the same manner.

What this practice means to anyone looking for signs of Fielding's

authorship in the published numbers of Common Sense is

obvious: we cannot now automatically exclude an essay from consideration

merely because it shows has and does where

Fielding would have used hath and doth.

Inspection of the manuscript, and collation of the manuscript with

the printed versions, reveal two other sources of possible confusion.

Molloy, for instance, was not above tampering with Fielding's phrasing

when, to his by no means infallible ear, it seemed infelicitous. Thus in the

second sentence of the manuscript Fielding's forceful declaration "that the

utmost Perfection of human Wisdom is Silence" is padded out by Molloy

to read, "that the utmost Perfection that human Wisdom is capable of

attaining to is, Silence"—a pointless adulteration of the original

which I

have ignored in transcribing the essay. Another such revision occurs at the

end of the first sentence of the penultimate paragraph, where Molloy

obliterated Fielding's own phrase and substituted the words "maintained in

It as long as he lived." Happily, Molloy did not take many such liberties

with Fielding's text. Even so, this essay in its published form presents an

additional, if no doubt minor, hazard to anyone trying to weigh its claims

to be Fielding's work: we would be

right in supposing that Fielding could not have written the feeble phrase in

the first example above, but we would be wrong to infer therefore that

Fielding had not written the essay as a whole. And finally, anyone seeking

Fielding's traces in the pages of the two-volume reprint of

Common

Sense may expect to encounter numerous pitfalls of another sort.

For,

though the essay as originally published includes Molloy's revisions as well

as a number of errors committed by the compositor, who in several places

misread the manuscript, the version in the reprint is more imperfect still;

besides preserving the faults of the original issue, it introduces others of its

own, including the deletion of four entire phrases.

For these reasons, then, the task of identifying Fielding's hand in the

published numbers of Common Sense cannot be undertaken

very

confidently. Without the hath-doth test to rely on, we have

lost

one simple means of narrowing the range of possibilities. The manuscripts

preserved at the Public Record Office are, of course, a considerable help

toward this end, and in some instances may serve to chasten the rash: if,

for example, we set aside the hath-doth test, the leader

published in the journal on 30 September 1738—an ironic allegory

of

corruption in English society written in the form of a "Letter from Common

Honesty to Common Sense"—sounds rather like Fielding; but, as the

manuscript proves, he was not the author.[10] And what about the issue of 23

December

1738, in which the author anticipates the satiric analogy between Walpole

and Jonathan Wild which Fielding would develop at length in his novel? If,

like W. R.

Irwin,[11] we had resisted the

temptation to attribute

this leader to Fielding chiefly because it fails the

hath test, we

may wish now to have another, closer look; the manuscript, unfortunately,

has not been preserved. I doubt, however, that this is Fielding's work:

though the basic device of the satire is identical with that of

Jonathan

Wild—and represents, moreover, the earliest known instance

of the

analogy after its original occurrence in

Mist's Weekly Journal

(12, 19 May 1725)—yet Fielding could not have developed the idea

in so

dogged a manner, and his humor, needless to say, is never so lifeless and

heavy-handed. A more playful piece that might well be his is the clever

satire of Theophilus Cibber (

Common Sense, 19 May 1739)

which takes the form of a brazen, hectoring epistle, partly in verse, from

"Pistol" to the editor—"Pistol" being, of course, Fielding's name for

Theophilus Cibber in

Tumble-Down Dick (1736) and

The

Historical Register, where he is made to strut and rant in a

similar vein.

[12] But again, there is no

manuscript to confirm the attribution.

Since all the extant manuscripts of the journal antedate 27-28 June

1739, when Walpole's agents confiscated them,[13] they offer no clues to the

authorship of

any essays published after that time. In my opinion, however, Fielding did

make at least one, and quite possibly two, further contributions to

Common Sense during the period before The

Champion began publication on 15 November. On 15 September

Molloy devoted his front page to two witty and learned letters from,

ostensibly,

two anonymous correspondents. The first is a political piece which begins

with a friendly caveat to the editor—"The Restraint, or Excise,

which

Wit may some Time or other suffer, will confine the Use of it altogether

to Manuscripts or Discourse; and even then, the Use of it may lead its

Owner into great Inconveniencies, if he has not the Art to check it, or let

it loose with Judgment and Discretion"—and proceeds through

references

to Tacitus and Juvenal, Bacon and Ralegh, to apply the lessons of history

to present politics, most particularly to the consequences of corruption and

luxury in high places and to the threat ministerial "Whisperers" post to

freedom of expression. The second is on a moral theme, being the droll

complaint of a man who has pored over many books hoping in vain that the

wisdom of the ancients might cure him of his favorite

vices—"

Talkativeness" and "

Intemperance in

eating and

drinking." Both these letters show

has and

does

instead of Fielding's usual archaisms; but, with some reservations about the

first, I believe they are his work. Certainly, as the "Mum Budget" essay

attests, few others at this time could speak more feelingly, or with such

humor and playful erudition, about the "great Inconveniencies" authors

might suffer owing to the "Restraint, or Excise," on "Wit" in Walpole's

England. And again, with "Mum Budget's" views on the wisdom of silence

in mind, there is, at least, a witty symmetry worthy of Fielding in this new

piece on talkativeness from a man who, though he has "a thousand Precepts

in [his] Budget against going too far," finds them all sadly ineffectual.

Might we not see these two letters, treating political and moral matters in

that humorous way so characteristic of Fielding's manner in

The

Champion, as a sort of preliminary exercise calculated to

demonstrate

his qualifications for conducting a periodical paper of his own? However

that may be, I do believe he wrote them.

Proving he did is a very different matter of course, perhaps for another

occasion.

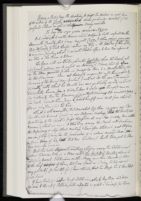

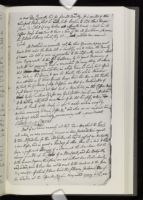

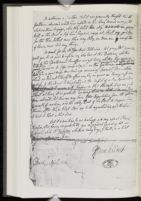

What follows is an annotated transcript of the manuscript in the

Public Record Office (Chancery Lane)—call number: SP9/35, items

215-16. The manuscript itself, comprising two folio sheets (12½ by

7¾ inches) with writing on both sides, is photographically reproduced

in the plates accompanying this article. In preparing the transcript, I have

tried to convey a sense of Fielding's original intentions. Whenever I was

confident that I could distinguish these from the changes introduced by

Molloy as he edited the copy, I have disregarded the latter in order to

restore Fielding's own phrasing and his own practice with respect to the

accidentals, particularly paragraphing. Unfortunately, though it is

comparatively easy to distinguish between author and editor in substantive

matters—Molloy's hand being quite different from

Fielding's— it is

virtually impossible to do so in the case of pointing. Elsewhere, in

his correspondence, Fielding tends toward minimal punctuation;

[14] but he may well have followed a

different

practice when marking copy for publication—and since the present

manuscript is the only such copy by him which has survived, there is no

basis for comparison. Some decisions affecting

capitalization—especially

the capitalization of nouns— were also difficult, since the form

Fielding

gives certain letters is constant, whether he intends them for upper or lower

case: this is true of his

m,

o,

s,

u,

v,

w, and occasionally his

a. When he means to capitalize these letters he simply writes

them larger; and size being a relative thing, his intention is not always

clear. In doubtful cases, therefore, I have followed his normal practice of

capitalizing substantive nouns. Finally, in annotating the essay, I have not

glossed biographical or political matters when these have been dealt with

above.

* * *