| | ||

Since the 18th century collation has been a standard procedure in editing Shakespeare. At first it sought lexical differences between editions; but recently variation within the same edition has come into focus, largely through the work of the late Charlton Hinman.[1] His mechanical collator and its adaptations[2] have revolutionized collation. Instead of comparing words

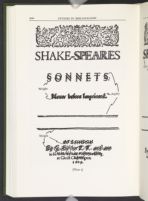

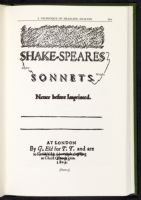

Let me illustrate the principle with an example from

Shakespeares Sonnets, 1609 that has hitherto escaped notice,

and in the process introduce a photographic method of collation that does

not employ expensive mechanical collators. The title page of the Q1 of

1609 has long been known to have two imprints. In the account of Hyder

Rollins, the authoritative Variorum editor, the title pages "represent an

identical setting of type except for the imprints."[3]

The alteration of the imprint, long known, seems to have been accompanied by something never guessed at. First there is horizontal and vertical displacement of rows of type between the two images, although identical letterpress is found in common text. The horizontal movement might, to some degree, be explained by application of different pressures in locking up the forme after the change of imprint (for collation of the surviving title pages reveals that the gross differences observed here correspond to the change of imprint). But the vertical displacement of type can be explained only by the transposing of a reglet from above to below 'SONNETS.'—or vice versa. This alteration occurs in conjunction with another, revealed by the fact that the two images of 'SHAKE-SPEARES' do not fully align with each other (see Pl. 2). This evidence can be readily understood by another manipulation of the photoimages (a procedure impossible on mechanical collators). The following plate is made as the former two except that the transparency is turned over and rotated 180° with the result that the two imprints can be

The explanation of the misalignment is now obvious: the first and third E's in the name have been interchanged; this feature, like that of the transposing of the reglet, coincides with the change in imprint. In the Wright title the first E (that in 'SHAKE') has a slightly narrower set than the two E's in 'SPEARE' and may represent a different fount. In the Aspley title this E with the narrower body is transposed with the second E of 'SPEARES'. The difference in the bodies of these transposed types throws off the alignment of '-SPEARES' up to the final S by altering the spacing before the hyphen. Of course, there is no change in length of the whole line.

The order of these changes, which coincide with the unlocking and adjustment of the page to alter the imprint, is not to be determined by strict bibliographical evidence. It is possible that in the unlocking of the page the

Let me now turn the techniques used here to a specific kind of problem that arises in close bibliographic scrutiny of any book—analysis of running headlines.

| | ||