The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| III. |

| III. |

| I. |

| II. | APPENDIX II |

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| III. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

II. APPENDIX II

THE CUSTOMS OF CORBIE

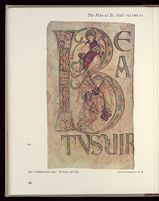

527. THE "CORBIE PSALTER," INITIAL LETTER

CORBIE PSALTER (CA. 800)

AMIENS 18, fol. Iv

The script of the psalter is that of the Maurdramnus Bible, the embryonic

Carolingian minuscule, possibly derived from North Italian uncial. Since the many

designs in the codex betray direct dependence on Byzantium, Jean Porcher (Karl

der Grosse III, 59-60; ill. p. 69 fig. 7) surmises that the artist came from the

Greek colony of Ostia near Rome to Picardy in the company of another Greek,

George, who became Bishop of Amiens, 769-798.

The CUSTOMS OF CORBIE

CONSUETUDINES CORBEIENSES

A translation by CHARLES W. JONES

of

THE DIRECTIVES OF ADALHARD OF CORBIE [753-826]

PREFACE

TO include in a book on the Plan of St. Gall a translation of Adalhard's Consuetudines Corbeienses hardly calls for

justification. The two documents have much in common. Both are examples of a type of ordinance that in the

Middle Ages were referred to as brevia, i.e., "briefs"—a designation which in modern general (and distinct from

legal) parlance is more appropriately rendered by the term "directives." Such administrative ordinances were

intended to make regular and generally uniform the usages and practices (consuetudines, i.e., "customs") of a

given institution.

The Plan of St. Gall delineates in the graphic language of the architect the aggregate of buildings of which an

exemplary Carolingian monastery should be composed, the manner in which they are to relate to one another,

and how they should be arranged internally. In a comparable manner, the Directives of Adalhard of Corbie set

forth in the form of a body of managerial directives what measures should be taken by the heads of the monastery's

various economic departments in order to guarantee an even and unfailing flow of food supplies and other

material necessities for the physical sustenance of life in the abbey of Corbie. One could not conceive of two

mutually more elucidating historical sources.

It is therefore with gratitude that I accept for inclusion in this book Charles W. Jones's masterful translation

of this unique and important document. It will be a valuable source of information for those who cannot read it

in its original language and of more than casual interest to those who are aware of the (in places exasperating!)

difficulties of interpretation presented by medieval texts of this nature. Jones's translation of Adalhard's Directives

is the first of this treatise in any modern language, so far as we know, and we hope to make it available in the near

future for broader distribution by means of a separate, more easily accessible edition. More than one hundred and

twenty years ago B. E. C. Guérard, one of the greatest students of the Age of Charlemagne, recognizing the need

for translations of primary sources of this type published a French version of another important managerial

treatise of the period, the famous Capitulare de Villis (q.v.), and thus made the subject of the management of royal

desmesnes available for study in a broad spectrum of neighboring disciplines. I have no doubt that Charles W.

Jones's translation of the Customs of Corbie will have a similar effect in broadening our historical perspective of the

monastic economy of the period.

TWO WAYS TO SHARPEN A SWORD UTRECHT PSALTER (CA. 830) fol. 35v

528.A

528.B

Utrecht University Library

THE CIVILIZING ACHIEVEMENTS OF THE CAROLINGIAN DYNASTY

CANNOT OBSCURE THE FACT THAT ITS POWER RESTED ON ITS PROWESS

IN WAR;

IT LOST THAT POWER WHEN IT CEASED TO BE CAPABLE OF

ANSWERING VIOLENCE WITH VIOLENCE.

Jean Porcher, The Carolingian Renaissance, p. 4

Sharpening by grindstone and whetstone may in fact show two stages, rough edge,

to finished, of one process. Fabrication and maintenance of arms were tasks of

major monastic centers, indicating their active military role. The Plan provides

such facilities (below, p. 65).

This illustration is for verses 2-4 of Psalm LXIII (64):

"Hide me from the secret counsel of the wicked . . . who whet

their tongues like a sword . . . ."

INTRODUCTION

By CHARLES W. JONES

THE year 822 is red-letter in the history of Corbie, of its ninth abbot Adalhard (753-826), and of the Emperor Louis I.

Although at Adalhard's request Louis renewed and extended the privileges of Corbie (Addendum I, 124; 100 fig. 530) the

moment Charlemagne had died, in the same year he banished Adalhard to the island of Noirmoutier (dépt. Vendée), off

the mouth of the Loire. Then, in a mercurial shift of policy, Louis restored him in the year 821. Though the reasons for

both the banishment[1]

and the amnesty are obscure, we may infer that Louis simply feared more intensely than did his

father Adalhard's Italian sympathies and tried to break up the coterie around young king Bernhard. Such a coterie would

have centered in Adalhard, the regent. With the stable Adalhard exiled, Bernhard unsuccessfully revolted against Louis,

who ordered him blinded. Bernhard died in consequence. His death, together with the death (11 February 821) of Louis'

close advisor, the monastic reformer Benedict of Aniane, deeply affected the emperor. Immediately he restored Adalhard,

who inherited Benedict's influence. These actions affected the course of Carolingian institutions, whether on the Bodensee

or on the Somme.

When Adalhard left Noirmoutier, he returned to Corbie long enough to prepare the Directives during the month of

January 822. Then he hastened on to Attigny, where Louis publicly humiliated himself as penance for his cruelty to Bernhard

and doubtless for his mistreatment of Adalhard and his brother Wala.[2]

According to Halphen, Attigny accentuated

the religious bent of the imperial government. From that event, unity of faith became surrogate for unity of empire: one

spoke of unity of empire and unity of church as equivalents. As all became subordinated to the cause of religion, the

Church dominated the life of the state. "The men of the Church were consulted before all others; after the death of Benedict

of Aniane, the bishops, abbot Adalhard of Corbie, his brother Wala the monk, made immediate impact on the emperor,

who ended by seeing only by their eyes and doing only what they desired."[3]

From Attigny Adalhard went on to Saxony. Long before, he had planned with Charlemagne to bring Christianity to

heathen Saxony; but during his exile his successors had established Corbeia nova (Corvey) in an ill-favored site at Hethis.

Adalhard now transferred it to a new site on the Weser at Höxter, where it soon became, as Hauck says, by far the most

important convent in Saxony.[4]

In such ways did Adalhard influence the Carolingian social pattern for Italy and Germany

as well as France.

The English queen of Clovis II, Balthilde, had founded Corbie on royal demesne between 657 and 661, by transplanting

Luxeuil monks, who subscribed to the Luxeuil use of the Rules of Columban and Benedict.[5]

The Irish customs evaporated,

leaving no trace in the Directives.[6]

After Balthilde, the royal patronage continued: her son Clothaire III gave Corbie six

other demesnes,[7]

and five other Merovingian kings, as well as the Carolingian Pepin III and Charlemagne, are recorded

patrons.

Carolingian Corbie was a model of culture—not only affluent but learned. It was on the main road from Britain to

Italy, an axis of Carolingian development. The brothers assembled an important library of classics, and copied more.

Like St. Gall, it was rich in the works of English and Irish writers. Adalhard himself, while in exile, ordered a copy of

the Tripartite History, which he then brought to Corbie; and Pope Eugenius II in 825 gave Corbie copies of the Hadrianic

Antiphons, which made the abbey a center of Roman liturgical tradition.[8]

The "Maurdramnus Bible"[9]

has sometimes

been called our first dated example of Caroline minuscule.

The residents of Corbie were in large part noblemen.[10]

Adalhard himself was a grandson of Charles Martel, and therefore

first cousin to Charlemagne. No lesser Frank could rule so proud a house.[11]

He had been instructed in the palace

school, inter palatii tirocinia, under the same masters as Charlemagne, cum terrarum principe magistris adhioitus.[12]

His

sister Guntrada was a lady-in-waiting at the court.[13]

His brother Wala, his successor at Corbie, was also a regent, legate,

and councillor.[14]

Adalhard, who had arranged Charlemagne's betrothal to the Lombard princess Ermengarde, quit the

court to become a monk when Charlemagne rejected her. But like his prototype, St. Anthony, he could not remain a

recluse; his studious concern with both the theory and practice of managing men forbade it.[15]

Management of the temporalities of Corbie required worldly wisdom. The Directives specify twenty-seven villas[16]

in

some form of tenure, but that number is far from exhaustive.[17]

For example, Corbie held substantial grants in newly

conquered Saxony before the foundation of Corvey, to which some grants were transferred. It is known that Corbie also

held villas in Alsace and the Rhineland.[18]

As with the portfolios of modern benevolent institutions, the holdings were

diversified. Adalhard evidently considered his abbey as consisting of four concentric operations: 1, the cloister; 2, the

compound, equivalent with the area visualized in the St. Gall plan; 3, the domain, made up of seven adjacent villas and

twenty more at a distance not exceeding sixty kilometers; and 4, a total feudality of indeterminate bulk, in allegiance to the

abbot, spreading across a considerable sector of empire, embracing not only the domain, but also distant tenures involving

a wide variety of rights and obligations, to which he does not allude.[19]

The Directives show that the economy of Corbie,

though primarily dependent upon produce from the villas of the domain, also fundamentally depended upon the use of

money; they reveal that the old support in kind was yielding to such far-flung operations.[20]

Like St. Gall, Corbie was an arm of theocracy. Alcuin's nickname for Charlemagne was "David;" for the emperor

stood at the head of the religious and secular life of his realm as did King David of old, who was both priest and warrior,

and in whose kingdom each secular act had its religious counterpart. Carolingian magnates simultaneously tried to balance

secular and ecclesiastical offices (pope-emperor; bishop-count; priest-vassal) and to unite their duties in single persons

(cancellarii and missi, originally secular posts now held largely by clergy; abbacomites, lay abbots). Artists now exercised

their ingenuity to apply the figure of the Christian warrior (miles Christi), popularized in the days of Roman persecution

by the Acts and Passions of the Holy Martyrs, equally to the knight on horseback who carried Conversion in his sword

and to the prelate who carried it in the sacrament.

Indeed, the interrelations, even in etymology, of the monastic court (co-hortus) and the secular court (curia) cannot

be unraveled. Corbie's economy centrally supported 350 to 400 Christian knights (miles Christi) in the divine task (opus Dei)

of liturgical procession toward the New Jerusalem.[21]

Though there is no record that he ever rode to secular warfare,

Adalhard was one of the royal prelates who made monk and knight two faces of the coin of Christian warfare. To support

400 knights, whether spiritual or temporal, was a logistical problem which depended for success on an even flow of goods

and services. Writing was a comparatively recent acquisition among the German rulers, but Adalhard had learned from

the heads of the royal court how valuable each preserved written document had proved to be for stabilizing power. Written

memoranda had been accepted as binding by the Franks ever since Insular missionaries like Boniface became involved in

Pepin's time onward, faith in the written order was established and accepted.

Adalhard solved his managerial problems by incorporating both custom and reform into writing.[22]

Incompletely transmitted

though they are, the Directives are our most specific and circumstantial economic document at a key moment in

the evolution of feudalism. The editors of the Corpus Consuetudinum Monasticarum have listed[23]

the works that in some

fashion might be considered rivals. The polyptych of Irminon is also valuable, but in a very different way. The two bear

somewhat the relation of the coronation charter and writs of the English Henry I to the Domesday Book of William I.

Adalhard's effective model was the Rule of Benedict of Nursia, with its reformation codicils, that regulated the claustral

division of the abbatial operation.[24]

Benedict had had no need for more; beyond his Italian cloisters lay not a theocracy

but an essentially hostile state, chaotic if not anarchic. Benedict walled out that world. But Adalhard on the contrary had

to build a bridge between his cloister and the friendly, benevolent empire. The transitional area was the compound and

domain, where the Chapter, headed by the deans, melted into the familia Corbeiensis, headed by the mayors. Both were

under the fatherhood of the abbas. Here Adalhard needed a rule.

Doubtless he prepared directives for each of the monastic officials charged with any extra-claustral responsibilities.

These would have included the provost, the deans, and the chamberlain. Not all have survived. What have survived are

those for the magister pauperum (I?, II),[25]

the custos panis (III), the hortolanus (IV), the cellararii, iuniores et senior (V, VII),

and the portarius (VI).[26]

A fragment (VIII) on the vestarius suggests that Adalhard may have extended Benedict's Rule

by issuing directives for some internal officials too; for instance, the bibliothecarius, cantor, hospitalarius religiosorum. But

the evidence is minuscule.

Naturally, there is no suggestion of written rules or memoranda for lay officials (vassali, maiores, actores, fabri). Among

Teutoni generally, only clerical fratres were expected to be literate.[27]

Charlemagne had learned the uses of literacy and

had pressed the abbeys to take some noble scions for tutelage. At St. Gall, for example, their number was considerable

before the end of the ninth century. But most monks regarded such intrusion of secularity an abuse. The reformers did

what they could to control mingling which they were not powerful enough wholly to prevent. There are faint suggestions,

no more, in the Directives that Corbie had a few external scholars, but Adalhard presumably would not favor the practice.[28]

At all events, we may doubt that any of them graduated to any other vocation than that of royal or episcopal cleric. And

it would be inconsistent with the evidence to believe that in the year 822 written regulations or directives governed secular

officials on the manors.

The diction of the Directives shows that the Carolingian proprietors were feeling their way toward a new orthodoxy

in feudal relations. Adalhard seems to choose his words rather loosely,[29]

using labels like prior, provendarius, maior, custos,

magister, and vassalus in overlapping and contrary senses. But with each year of Louis's reign these tenures became more

particularized, as the discriminating research of Professor Ganshof and other recent scholars shows. The Directives record

a moment of rapid social change: vassalus is equated (402.1) with homo casatus, "a housed man."[30]

However, the casa

vasallorum (367.8) is a separate hospice within the compound to house visiting vassals. Are they there to transact business

in goods and services, to render homage, to worship? Or is their servitium as a military guard? The curticula abbatis (366.2)

is etymologically only a "modest atrium," but is developing into a domus or palatium, and also into a curtis dominica.[31]

At Corbie domus is not necessarily an aristocratic word; note the domus infirmorum. Lesne too forcefully contended that

there is no evidence of mensae, or inalienable livings for the cloistered, at Corbie, though they were already appearing

elsewhere. He maintained[32]

that Adalhard was himself a monk, not a lay abbot, and that only under civil governors did

monks demand protection from those who would waste their substance in secular affairs. But this is a point of view from

later reforms: under Charlemagne, Adalhard was both monk and courtier. Many of the Directives concern specific differentiations

between what is due allowance for the cloister—monks, prebends, and matriculants—and what lies outside their

call. The abbot clearly states that specific lands have been ceded to the provost and deans, that is, to the fraternal officials.

All else doubtless was secularly managed by the abbot in some capacity of vassalage.

529. LUTTRELL PSALTER (CA. 1340)

BRITISH MUSEUM ADD. MS. 41320. fol. 66b, detail

[By courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum]

MAN WITH BROAD-AXE, DOG, AND GOOSE

Adalhard describes equipment for gardeners (below, p. 109 and notes, 108) who

were to have "hatchets and pick-axes"; the sophisticated broad-axe of the later

Psalter is more appropriate gear for a forester or game warden.

Adalhard is a diplomatic innovator. He is quite proud of his solution[33]

of the problem of tithes in kind from distant

villas, but is wary of his brothers' reaction against his change.[34]

He introduces other reforms (e.g., banishment of seculars

from the kitchen; establishment of tithed sheep in the claustral sheepfolds) in an easy spirit of conciliation, suggesting

that his innovations be tried only until better methods are found. His grants of privileges to millers in exchange for increased

production is masterful. His style suggests that he dictated his remarks to a secretary: it shows haste, and his

sentences contain administrative jargon and circumlocution. But he has exceptional ability to make himself understood,

to both the ninth and the twentieth centuries. Only Benedict's exemplary Rule is a model for this unique work.[35]

The Directives of Corbie and the Plan of St. Gall are remarkably interrelated; for they were prepared at almost the

same historical moment, under the impact of a political and social change which was itself unifying. The two abbeys were

comparable in aims and power, though ethnically separated. Wiesemeyer writes: "Well-known facts show that Corbie

was the most important monastery of Northern France, comparable in all ways with Saint-Denis, Saint-Gall, and Monte

Cassino." In the Plan of St. Gall and the Directives we have the specifications of abbey life, easily bridging the gulf between

spiritual and temporal and manifesting how slight was that separation in the days of Louis I and Benedict of Aniane.[36]

THE ADDENDA

I have appended four Addenda. Addendum I, the Emperor Louis's charter of immunities (29 January 815), confirms

that issued by Charlemagne (16 March 769) to Abbot Hado of Corbie,[37]

as Charlemagne had confirmed the immunities

granted by the Merovingian kings and his father Pepin before him. The editor Levillain has persuasively but not irrefutably

argued that this charter was presented to the second Adalhard ("the Younger") rather than to our author; however,

any doubt about who received it does not affect the precision of its contents, which clearly indicate the legal status of all

Corbie property alluded to in the Directives. Addendum II, a document contemporary with the Directives, was issued

at the abbey of St. Wandrille[38]

(Fontanella), about seventy-five air miles southwest of Corbie on the lower Seine River.

Fontanella and Corbie were of comparable size. Addendum III indicates by genealogy the relationship of Bernhard's

family, including our Adalhard and his brother Wala who succeeded him to the abbacy, to the royal Carolingians.

Addendum IV, an epitaph commemorating Adalhard's death, was written shortly after that event by Paschasius Ratpertus,

monk of Corbie and later its abbot.

THE TEXT

Adalhard's Directives survive in the two tenth-century manuscripts (bound together at Corbie before the thirteenth century),

in Dachery's printed edition of 1661 drawn from an early (ca. A.D. 900?) manuscript now lost, and some fragmentary copies

made in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries essentially from the previous items. Four printed editions preceded

Semmler's. The two surviving early manuscripts agree with each other neither in contents nor arrangement, nor with

Dachery's edition.[39]

Professor Émile Lesne (1925, 385-420) proposed that Adalhard had originally prepared separate directives for each of

his major officials:

"The brevis dictated by Adalhard in 822 was composed of a considerable number of separable items, though forming a continuous

series. Presumably, either because of the natural disruptions among the separated letters as sent to each monastic official concerned, items

which quite possibly consisted of small gatherings or detached sheets, or simply because of the deterioration of the archetype or its early

copies, the text has come down to us in the shape of fragments very diversely chopped up by the scribes, who doubtless had at hand only torn

or partially illegible folds. [p. 418] . . . the three manuscripts together preserve, despite some easily identifiable additions, each partially

and in different grouping, the essential contents which Adalhard drafted in 822 [p. 419]."

Professor Semmler, in preparing his excellent edition ("Consuetudines Corbeienses," Corp. Cons. Mon. I, 1963, 355-422),

adhered to Lesne's proposals while altering important details in the light of convincing evidence. He relegated the later

interpolations to an appendix and changed some parts of Lesne's suggested arrangement.[40]

I have translated Semmler's edition without alteration. "The Rubrics (Capitula) of the Abbot, Dom Adalhard" (below,

pp. 121-122) are not to be found in an extant manuscript, but were published by Dachery's co-worker, Jean Mabillon,

in the Acta (saec. IV, pars prima), 1677, 757-58. Mabillon transcribed them from Dachery's manuscript, now lost; the

consensus is that they are authentic.

530. THE CHARTER OF LOUIS THE PIOUS (9TH CENTURY)

BIBLIOTHEQUE NATIONALE, MS 2718, fol. 80 v

[courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris]

The origins of ancient stenography are obscure. Isidore of Seville may be the source of the later phrase "Tironian notes":

"At Rome Cicero's freedman, Tullius Tiro, first worked out shorthand signs, but only for prepositions . . . Finally Seneca, by contraction and division of

all words and numbers, brought the total number of signs to five thousand" (ETYM. I, xxii).

In the poverty of the seventh and early eighth centuries, monastic scribes sometimes saved precious vellum by employing shorthand. From civil offices

diplomas employing it survive from Merovingian notaries of the late seventh century, but only under Louis I did tachygraphy predominate. Under the

Carolingians CANCELLARII (a term of Byzantine origin) replaced REFERENDARII as chief notaries, and under Louis I the archchancellor, in charge of the

emperor's seal and therefore of highest responsibility, was drawn from the episcopate, usually a trained monk.

This charter is translated on page 124, below. Contractions and abbreviation signs in the Plan of St. Gall are discussed above, page 11.

Semmler describes the manuscripts and printed editions in Corp.

Cons. Mon. I, 1963, 357-63, and tabulates their differences. The four

essential documents are:

A. Paris, National Library MS lat. 13908, fols. 1r-22v (copied after

A.D. 986).

B. The same MS, fols. 29r-53v (according to Levillain, 1900, 333-349,

copied in the 10th century from a recension prepared A.D. 822-844).

S. L. Dacherius, ed., Spicilegium IV, Paris 1661, 1-20 (according to

Levillain, loc. cit., copied from a lost Corbie MS of a recension

prepared between 844 and the 10th century).

M. Paris, National Library MS lat. 17190, fols. 66r-73v (copied ca. 1700

for the Benedictine editor Martène from Dachery's MS, supplying

sections which Dachery had omitted).

"Factum est, ut sine accusatore, sine congressu, necnon sine audientia

atque sine iudicio iustitia plecteretur in eo." Vita Sancti Adalhardi

. . . Radberto ix, 30 (Mon. Germ. Hist., Script. II, 1828, 527; Acta

Sanctorum 1863, 101). Cf. Anonymi Vita Hludowici, 19 (Pat. Lat. CIV,

941B-C).

Levillain, 1902, 199-200, would extend Louis's rancor against Adalhard

back to Charlemagne's difficulties with Gerberga, wife of Carloman.

At all events, as he notes, endowments declined at Corbie during

Charlemagne's rule. Noirmoutier (Hero), like St. Michel, Lindisfarne,

and other offshore retreats, is a peninsula at low tide. Evidently Adalhard

was accompanied by a considerable retinue, for at Noirmoutier he

ordered Corbie companions to copy the Historia Tripertita (now Leningrad

MS F v. 1, 11); according to Leslie Jones, 1947, 377, "Nearly every

quaternion shows a change of scribe." This fact argues for his continual

close knowledge of Corbie affairs during the exile. According to the

lists of abbots of Corbie in 12th-century MSS, a second Adalhard, "the

Younger," filled his post during exile, but the evidence is dubious

(cf. Levillain, 1902, 93 and 317-19; Irminon, 1844, II, 338-39).

Annales regni Francorum, anno dcccxxii (ed. Kurze, Scriptores

rerum Germanicarum, 1895, 158); Cambridge Medieval History III, 12.

Ratpertus (Vita sancti Adalhardi xiii, 49) states that Adalhard was stricken

with fever at Corbie, evidently at the time of composition of the Directives.

Halphen, 1949, 249-50; Amann, 1947, 210-17; Folz, Le couronnement

imperial de Charlemagne, 1964, 214-15. It would be uncritical

to generalize from the single record of relations between Benedict of

Aniane and Adalhard: "Contentio fuit inter Adalhardum et Benedictum"

(Hafner, 1959, 140). The contention seems not to have centered in any

fundamental policy, but only in human relations between zealot and

diplomat.

Vita sancti Adalhardi, 16 (Acta sanctorum, 107). Helmut Wiesemeyer,

"La fondation de l'abbaye de Corvey," Corbie abbaye royale,

105-33; see also Karl der Grosse, I, 472; II, 282, 286.

Columban founded Luxeuil A.D. 590; the Benedictine Rule spread

through Francia in the seventh century (Lesne, 1910-43, I, 379, 399).

The Corbie "ab script" was especially cultivated under Adalhard; it

was originally called "Lombardic," and confused with script from

Bobbio, possibly because both scriptoria derived their form from

Luxeuil. See Jones, 1947, 376-80; Françoise Gasparri in Scriptorium

XX (1966), 265-72; Ooghe in Corbie abbaye royale, 1963, 267-68. Such

traditions doubtless fortified the interest of both Adalhard and Wala in

Lombardy.

But see Verhulst and Semmler, 1962, 253. On the advance of

Benedictinism under Charlemagne, consult Semmler in Karl der

Grosse II, 255-89, esp. 262-67, 287.

Jones, 1947, 196, but see Bischoff in Karl der Grosse II, 237-39;

New Oxford History of Music II (1954), 100. "Probably Adalhard, the

famous abbot of Corbie, should get the credit [for the Glossaria Ansileubi];

for apparently the compilation was made at Corbie in Adalhard's

time. And what a huge compilation it is! (It fills, even with all our

compression, over 600 printed octavo pages.) What a noble record of

French learning in Charlemagne's time!"—Wallace Martin Lindsay in

Bulletin DuCange, III, 1927, 97-98. An examination in computus administered

to prospective teachers in A.D. 809 mentions Adalhardus

venerabilis abbas as authority on lunar movements (Mon. Germ. Hist.,

Epistolae III, 1934, 569-72; Jones, 1963, 25). For Adalhard's central

position in the Filioque controversy (Procession of the Holy Spirit) see

the exposition of Henri Peltier in Corbie abbaye royale, 1963, 63-65,

and references.

For a discussion of Adalhard's literary activity as well as for the

English tradition in the abbey, see W. Stack and H. Walther, Studien

zur lat. Dichtung (Ehringabe f. Karl Strecker), Dresden, 1931, 18-21;

Paul Bauters, Adalhard van Huise, Audenarde, 1965; Fr. Prinz, Frühes

Monchtum im Frankenreich, Munich-Vienna, 1965, 521-23.

Parts are now Amiens MSS, B. M., 6, 7, 9, 11, 12 and Paris MS. B.N.,

Lat. 13174 (E. A. Lowe, Codices Latini Antiquiores VI, 1953, No. 707;

Scriptorium XX [1966], 265-72; Karl der Grosse, ed. Braunfels II, 186;

No. 368 in Karl der Grosse [Catalogue], 209). The "Maurdramnus

script" can be examined in Amiens MS. 18, "the Corbie Psalter."

Maurdramnus was abbot A.D. 772-780 (Jones, 1947, 385); Ooghe in

Corbie abbaye royale, 1963, 273-78 (both with facsimiles).

H. Fichtenau, The Carolingian Empire, 1957, 167, citing Ratpert,

in Vita Sancti Adalhardi, col. 35. Ewig, Karl der Grosse, I, 166, calls it

"Ausstattung männlicher Nebenlinien," and Notre-Dame de Soissons,

a somewhat affiliated nunnery, "Ausstattungsgut weiblicher Angehöriger

des Konighauses."

Karl der Grosse, I, 163. See the genealogy of the Carolingian kings

and of Adalhard's family, p. 127. Adalhard gave his patrimonial lands

near Tournai and Audenarde to Corbie (Vita sancti Adalhardi, 8;

Pat. Lat. CXX, 1512; Levillain, 1902, 247).

Ratpert, Vita sancti Adalhardi, 7 (Mon. Germ. Hist., Script. II,

525); Lesne, 1910-1943, V. 34. Ratpert's elegaic eclogue on Adalhard

is in Mon. Germ. Hist., Poet. Lat., III, 45-51. After admission to Corbie,

Adalhard spent a period at Monte Cassino (Vita, 3) where he may have

first met Paul the Deacon, who later wrote:

"Sooner a recidivous Rhine retrace its stream, / Sooner a bright Moselle flow

backward to its source, / Than my love let escape from out of my heart / The

dear, sweet, ever-cherished name of Adalhard. / Thou too, if thou wouldst

bask in grace of Christ, / Through every hour be mindful of thy Paul."

—Carmen xxvi (Mon. Germ. Hist., Poet. Lat. I, 62)

Alcuin, whose nicknames for court companions are demonstrably

meaningful (Karl der Grosse I, 43-46), called Guntrada "Eulalia" and

Adalhard "Antonius."

Another brother, Bernher, is known only as a monk at Lérins

(Peltier in Corbie abbaye royale, 73), though we may guess that he was

exiled there. Lérins, St. Honorat's great foundation, was reformed by

agents of Benedict of Aniane ca. 800 (Karl der Grosse II, 260). A fifth

child, Theodrada, a nun (Vita sancti Adalhardi, col. 61; Karl der Grosse I,

81) doubtless became abbess of the royal retreat, Notre-Dame de

Soissons (Karl der Grosse I, 163, n. 164).

There is some doubt whether Adalhard was involved with the

Ermengarde affair (770) or Desiderius (771); Ratpert asserted the latter.

See Èmile Amann, L'époque carolingienne, 1947, 52. Desiderius, after

defeat, retired to Corbie (ibid., p. 57) where we may imagine that his

association with Adalhard confirmed the latter's Italianate predilections.

Archbishop Hincmar's Pro institutione Carlomanni regis (ed. M. Prou,

Bibl. de l'Ecole des Hautes Etudes 58, 1885) seems largely (cc. 13-36)

copied from Adalhard's De ordine palatii (On the Structure of the Royal

Court), a work of unknown date which has disappeared. Halphen, in

Revue historique CLXXXIII, lff, and others, have doubted this ascription,

but Fleckenstein in Karl der Grosse I, 33, lists the authorities; cf.

Ganshof in Karl der Grosse I, 360, n. 77.

Villa has no fixed meaning, but is comparable with parochia. A

record of Teodrada's Notre-Dame de Soissons, of A.D. 858, equates the

abbess's two villas with seventy-eight manses: "Abbatissae quoque pro

opportunitate potestatis se praeparet, duas ei villas delegavimus servituras

. . ., id est mansos lxxviii." See Lesne, 1910, 31n. This roughly accords

with the data of the Polyptyque de l'abbé Irminon, ed. Guérard. "Mansi,

agricultural holdings whose normal size in Northwestern Gaul was 10-18

hectares (25-48 acres)." François L. Ganshof, Feudalism (Torchbook

ed.), 37. According to the Polyptyque, the lands of the abbey of St.

Germain des Prés, ca. 815, were 35,012 to 38,141 square kilometers,

and the number of individuals about 10,282; see Ferdinand Lot in

Le moyen àge XXXII (1921), 10-11.

"Very clearly then, the villas listed by Adalhard constituted the

villae dominicae of Corbie, as opposed to villae constituting the beneficium

of the vassi, often called villae beneficiatae in other abbeys." Verhulst

and Semmler, 1962, 235.

Weisemeyer, Corbie abbaye royale, 114; Verhulst and Semmler,

1962, 234. Carloman's Queen Gerberga gave some of these lands; see

Levillain, Examen critique, 1902, 240.

Compare the holdings of the equally distinguished abbey of St.

Wandrille (Fontanelle), situated on the Seine below Rouen. According

to the Deeds of the Holy Fathers of Fontanelle (ed. Dom F. Lohier and

R. P. J. Laporte, Gesta Sanctorum Patrum Fontanellensis Coenobii, 1936,

82): "These are the total holdings of the abbey according to the inventory

which the invincible King Charles ordered Landric, abbot of

Jumièges, and Richard, the count, to prepare in the twentieth year of

abbot Witlaic's rule, which was the year of his death (A.D. 787). First,

of those holdings intended for the abbot's personal use and for the

subsistence of the brothers, there were found to be 1313 full manses,

238 half-manses, and 18 garden-plots—a total of 1569—plus 158 undeveloped

manses and 39 mills. As for released benefices, there were

2120 full manses, 40 half-manses, and 235 garden-plots—a total of 2395

—plus 156 undeveloped manses; these have 28 mills of their own. The

sum total of present holdings, considering full manses, half-manses, and

garden-plots, is 4264, excluding those villas which Witlaic released to

the king's men or even granted to others under usufruct—something

that should under no circumstances have been done."

A mansus integer, or full manse, has been defined in note 16; or it may

be calculated as consisting of two or more bunnaria, or 2.56 hectares, of

arable land, to which must be added the common forest lands, meadows,

and vineyards. For the sub-standard garden-plots (manoperarii) the

holders contributed only manual labor, not carts or draft animals. There

was always a good deal of undrained or marginal land which made up

the domain; such land is listed in the inventory as absi, or undeveloped

manses. The category of mansi ad usus proprios, reserved for direct

support of the abbot and abbey, compares with what I have called

operation 3 at Corbie; and the beneficii relaxati, or released benefices,

with operation 4 (see preceding p. 95). Professor Ganshof wrote (The

Cambridge Historical Journal, 1939, 162), "It is certain that ecclesiastical

lords regarded themselves as proprietors of the benefices granted

by them to their vassals, and the same naturally holds good for lay

seigneurs." See François L. Ganshof, Feudalism (Torchbook ed.), 162.

Doubtless a large fraction of the benefices yielded the nona, as income

under the Capitulary of Herstal (A.D. 779, Mon. Germ. Hist., Capitularia

I, No. 20, 50). See Ganshof, ibid., 38-39, and I, 341, 349. The Council

of Aachen, 816, ruled that external estates must be managed exclusively

by laymen.

Verhulst and Semmler, 1962, 123, 249-51; cf. Karl der Grosse I,

534-36. There were many mints in the time of King Pepin, but in 804

Charlemagne issued a Capitulary (Thionville, c. 18) limiting the coinage

to the emperor's palace: "De falsis monetis, quia in multis locis contra

justitiam et contra edictum fiunt, volumus ut et nullo alio loco moneta sit,

nisi forte iterum a nobis aliter fueri ordinatum. (Regarding the coinage,

which against law and order has been produced in many places, we

decree that it should not be produced at any other place unless in

exceptional circumstances we should authorize it anew at some other

locality.)" The figure on p. 122 shows a coin by the abbot of Corbie

believed to have been minted shortly after the abbey's founding.

Corp. Cons. Mon., I, XIII-XLIX. Verhulst and Semmler, 1962,

247, following Ganshof, say that in conformity with the Capitulare de

villis (Mon. Germ. Hist., Cap. I, 32, 85-86) one-third of the production

of the villas went to the needs of the domain, one-third for sale, and

one-third for the needs of the monastery. Of course the tithe was first

subtracted from all. The Directives treat only the tithe and the last

third.

The Admonitiones, pp. 121-22, treat claustral problems. They are

topics to be dealt with orally in meetings of the Chapter, and Benedict's

Rule is their constitution. Hafner gives four versions of the reform texts

of Corbie use.

See I, 128, 326, and 335; Verhulst and Semmler, 1962, 265-66;

also the excellent chapter in Fichtenau, 1957, "The Poor," 144-76.

Before the reforms, there was a custom for the revenue to go to the

cellarer for eleven months a year and to the porter for the month of

December (Lesne, 1910, 29).

Based on Benedict's Rule, chap. 66; see also Lesne, 1910-1943,

I, 379. Compare Lesne, 1925, 419-20, for a slightly different estimate

of the contents of the archetype.

Cf. Lesne, 1925, 419-20; James Westfall Thompson, The Literacy

of the Laity, 1939, 27-52, who quotes (p. 28) Pirenne, "No one wrote

except the clergy."

Lesne, 1910-1943, V, 319, 433: "The school at Corbie in the ninth

century is clearly a school exclusively for oblates." But the remarks on

clerici in the Directives (Cons. Corbeienses, 366) do not support that statement,

and the statement about clericis extraneis (text, note 60) seems to

be indisputable evidence to the contrary. The Council of 817 forbade

external scholars in monasteries: "Ut schola in monasterio non habeatur

nisi eorum qui oblati sunt" (Corp. Cons. Mon. I, 474).

Pierre Héliot, "Die Abtei Corbie zur den normannischen Einfällen,"

Westfalen XXXIV (1956), 133-41, notes how the Directives and the

Plan of St. Gall complement each other and he lists, pp. 138-39, all the

buildings alluded to by Adalhard. He derives a lay school at Corbie

from the Vita S. Anscharii, and places it outside the cloister (p. 138).

M. L. W. Laistner, Thought and Letters in Western Europe, 500-900

A.D., rev. ed. 1957, p. 209, on the basis of statements in the Vita Anskarii

(i.e., Bibliotheca hagiographica Latina, no. 544) suggests that St. Peter

was the schola exterior for Corbie.

See above, note 19, and Ganshof, 1939, 151-53, and Feudalism,

ed. cit., 5, 25. Possession of a benefice of four mansi normally entailed

military service, and twelve mansi bound a vassal to mounted service

(Ganshof, 1939, 160). On monastic military obligations, see I, 342,

and n. 21. By capitularies of Carloman, Pepin III, and Charlemagne

vassals, but not brothers, were held for military service.

Lesne, 1910-1943, VI, 314ff; Verhulst and Semmler, 1962, 120.

Note the discussion of domus dominus in K.-J. Hollyman, Le développement

du vocabulaire féodale en France, 1957, 90-97; says H.-F. Muller,

"Mais la religion devait donner à ces mots toute leur force nouvelle."

For casa vasallorum see Héliot, op. cit., 139, n. 47.

Lesne, 1910, 26-37, 70, 114; 1910-1943, VI, 224; Verhulst and

Semmler, 1962, 235, n. 163, but see p. 114. Adalhard in fact speaks of

villas "quas praepositus specialiter in ministerio habet" (Consuetudines

Corbeienses, p. 375, line 8; cf. p. 418, lines 15-16); cf. Lesne, 1910,

137-38. In A.D. 681 all the property of Corbie was exclusively in the

prerogative of the abbot (Lesne, 1910-1943, I, 287).

"Some parts of Charles' empire were unaccustomed [to the use of

coins] and regarded it with mistrust."—Grierson in Karl der Grosse I,

535. Adalhard does not mention money, but it is evident that his proposal

depends upon it. See note 20, above.

Héliot, 19-41, describes the architectural layout of Merovingian

and Carolingian Corbie with the Plan of St. Gall in mind (see p. 30);

but the data are sparse.

CONTENTS

CONSUETUDINES CORBEIENSES[41]

| 356[42] | page | ||

| A | DIRECTIVES, OR BRIEFS, OF ADALHARD | 103 | |

| I. PREBENDS | 103 | ||

| II. THE POORHOUSE | 105 | ||

| III. THE GRAIN SUPPLY | 106 | ||

| IV. THIS IS THE MANAGEMENT OF THE GARDENS | 108 | ||

| V. THE MANAGEMENT OF THE REFECTORY OR BROTHERS' KITCHEN | 109 | ||

| VI. THE GATE AND TITHES | 111 | ||

| VII. THE NUMBER AND ALLOTMENT OF SWINE | 118 | ||

| VIII. FINALLY, THE BROTHERS' VESTRY | 120 | ||

| B | RUBRICS OF THE ABBOT, DOM ADALHARD, WITH RESPECT TO INSTRUCTIONS IN CONGREGATION |

121 | |

| C | FRAGMENTS OF CHAPTERS | 123 | |

| I. THE CANONICAL HOURS | |||

| II. THE SILENCE TO BE MAINTAINED IN DORMITORY & WARMING-ROOM | |||

| D | ADDENDA | ||

| I. THE CHARTER OF LOUIS THE PIOUS at Aachen, A.D. 815 | 124 | ||

| II. THE CONSTITUTION OF ANSEGIS, ABBOT OF FONTANELLA, A.D. 823-833 | 125 | ||

| III. A GENEALOGY: THE CAROLINGIAN KINGS & ADALHARD'S FAMILY | 127 | ||

| IV. PASCHASIUS RATPERTUS: ON THE TOMB OF ABBOT ADALHARD OF CORBIE | 128 |

531. SEAL OF LOUIS THE PIOUS (9TH CENT.)

BIBLIOTHEQUE NATIONALE, PARIS, CABINET DES MEDAILLES

actual size: 38 mm in length

Seals (SIGNA or SIGILLA) were used in antiquity to impress wax or clay on

documents or boundles to assure classification or privacy; but among illiterate

Merovingian sovereigns seals replaced signatures as authentication of public

documents. The Carolingians, IN RENOVATIONE IMPERII, revived a Roman

custom of using a symbolic effigy—not a portrait of the reigning sovereign—

on the seal. To it they added the sovereign's name and title. Thus, the image

on the seal of the Emperor Louis I is the bust of a Roman, evidently Commodus

(see H. Bresslau, Handbuch II2, 550, 559). Charlemagne and successors

also used monograms and BULLAE together with or as a substitute for seals.

The inscription surround of the laurel-crowned bust on this seal reads:

XPE PROTEGE HLODOVVICUM IMPERATORE ("Christ guard Louis the

Emperor").

Notations of page and subsection numbers which appear in italics in the left and right margins

throughout the following translation refer to corresponding sections in Semmler.

Material enclosed <in angles> indicates editorial additions which do not appear in the Latin texts.

[A]

DIRECTIVE

WHICH ADALHARD, RETURNING TO

CORBIE IN THE YEAR OF THE INCARNATION OF THE

LORD 822, IN THE MONTH OF JANUARY, IN THE

FIFTEENTH INDICTION, & IN THE EIGHTH YEAR OF

THE IMPERIAL REIGN OF THE GLORIOUS LOUIS

AUGUSTUS, ORDERED TO BE PREPARED.

<i>

I <PREBENDS>[43]

<I.1 THE NUMBER OF PREBENDS>

During our tenure these are the prebends who ought regularly

to hold appointment, with equal ranks and full-time duties.

If one of them should die, another should immediately be

appointed, so that the full quota may always be maintained.

And no further addition should be made to that number,

although there may at times be extra clerks, like Salvaricus and

some others who are attached to that cadre[44]

at present, or

certain laymen like those who are a part of that cadre—the

Vinedi, and Gerola, and Bruningus the Saxon, or the brother of

Bituradus. Even if other clerks or laymen are sent, still they are

not to be added to that number of 150. They must always be

counted and rationed individually, according to a separate

allowance for each of them, as ordered by whoever is in charge

at the time. But under our tenure those 150 are to have uniform

rations, just as today they are provisioned through the several

service offices, some in one manner, others in another. So in

consequence, it has not been necessary to write down the

procedure here, since it is well known both to the givers and to

the receivers from daily practice. And the executive officers

themselves, that is, the chamberlain, the cellarer, and the

seneschal, each have their own directives on the subject.[45]

THE CLERKS[46]

Twelve novices,[47]

seven other clerks. From among the latter,

two are assigned to the cellarer, one to the brothers' laundry,

one to the abbot's garden,[48]

three to the infirmary.[49]

The other

duties which clerks ought to perform should be performed by

the novices. The point is that only as many novices should be

placed in the cloister as are able to perform all the necessary

internal duties and are of our community.[50]

In this way they will

not dare to gainsay anything and will conform with what is

proper just as if they were officials, and because of their vocation

or spiritual life they should look beyond the provost and dean[51]

to the wardship of St. John.[52]

And they are never to be left

without supervision, lest the spiritual life of the monastery be

defamed because of some misbehavior on their part.

Likewise the Laymen[53]

Almsmen[54]

twelve, laymen thirty. To the first shop six: cobblers,

three, for horses two, for the fulling-mill one. To the second

shop seventeen: one of these for the shop, six blacksmiths, two

goldsmiths, two cobblers, two shield-makers, one parchmentmaker,

one saminator,[55]

three carpenters.[56]

To the third shop

three: two porters to the pantry and dispensary, one to the

infirmary. Two gararii,[57]

one at the woodpile at the bakery,

one at the center gate, four carpenters, four masons, two

physicians, two to the vassals' lodge. These are within the

monastic quarters.

matricularii: "Poor men acting as servants for the up-keep of the

church"—Niermeyer, 663. > matricula, "list of poor" = marguilliers.

See Lesne, 1910-1943, I, 380-85; Peltier, 72.

And those outside the Monastic Quarters[58]

To the mill twelve, to the fishpond six, to the stable two, to the

gardens eight, to the coachhouse seven, to the new orchard two,

two shepherds, to the stockyard one.

Section 3 specifically differentiates the locus Corbiensis, which may

have had a surrounding wall, from the villae Corbienses which lie beyond.

Within the first is the cloister, or locus internale, of the brotherhood.

Verhulst and Semmler, 1962, 119, n. 134.

clerici: all those below order of diaconi who are subject to scholastic

discipline. Verhulst and Semmler, 1962, 259 n. 279.

pulsantes, as at Tours (Verhulst and Semmler, 1962, 259 n. 281);

cf. Benedicti regula, chap. 58; ed. Hanslik, 1960, 133-38; ed. McCann,

1952, 128-33; ed. Steidle, 1952, 275-79; also see I, 311ff.

curticulum abbatis. Cf. Institutio Angilberti, Corp. Cons. Mon., I, 300,

l. 22; Verhulst and Semmler, 1962, 261 n. 295.

familia. This distinction was confirmed in the Capitulare monasticum,

42 (Mon. Germ. Hist., Capit. I, 346); Verhulst and Semmler, 260 n. 285.

The distinction between external students, usually "canons secular,"

and internal students, usually oblates, was becoming more definite (see

above, p. 97).

praepositum et decanum: Verhulst and Semmler, 1962, 261-64; praepositus

is often considered identical with prior (see I, 331-32), but the

words "abbati vel priori vel praepositis" (Corp. Cons. Mon. I, 418,

line 15) indicate two positions at Corbie.

"Et ipsi ministeriales habent inde singuli breves suos, id est camararius,

cellararius et senescalcus." See Lesne, 1925, 391; see I, 333ff.

<I.2>

<THE FOOD OF THE PREBENDS>

The Loaves of Bread to be Distribution[59]

| . . . to the stable 3 | Carpenters 4 |

| At the coachhouse 1 | Masons 4 |

| Goatherd 1 | 10 millers receive 15 loaves |

| 46 Additional | At the fishery 6 |

| Physicians 1 3 | At the gardens 8 |

| Albuinus | At the coachhouse 6 |

| Hartlaium | At the vineyard 1 |

| Ragemboldus | At the stockyard 3 |

| Guntuinus | Sheepherder 1 |

| Vulgerus | Three infants |

| Letramnus 1 | Additional |

| Filibertus 1 | At the pantry 8 |

| 46. These receive | At the marmorum[60] 2 |

| panem sprimatum[61] | Erluinus |

| Almsmen 9 | And Wandilt |

| Laymen 30 | And Bertus |

| Of the first shop 4 | And Otger 1 |

| Of the second shop 10 | Infirmum 1 21 |

| Of the third shop 2 | Millers 3 |

| At the second gate 1 | Loaves 8 106 |

| At the infirmary 1 | 135 |

| At the middle gate 1 | |

| At St. Alban's gate 1 |

At what Times Drink is Given

| December 25 | Nativity of the Lord | Moratum[62] |

| December 26 | St. Stephen's | Not moratum but drink[63] |

| December 27 | St. John's | Not moratum but drink |

| January 1 | Circumcision of the Lord | Drink |

| January 6 | Epiphany | Moratum |

| January 30 | St. Balthilda's | Moratum |

| February 2 | Purification of Saint Mary | Moratum |

| March 12 | Gregory's | Drink |

| May 1 | Philip's and James' | Drink |

| June 22 | Paulinus' | Drink |

| June 24 | John's | Moratum |

| June 29 | Peter's and Paul's | Moratum |

| July 4 <sic> | Martin's | Drink |

| July 20 | Dedication of St. Stephen's | Drink |

| July 25 | James' | Drink |

| July 28 | Dedication of Peter's | Drink |

| August 3 | Invention of Stephen | Drink |

| August 10 | Laurence's | Drink |

| August 15 | Assumption of Mary | Drink |

| August 25 <sic> | Bartholomew's | Drink |

| September 8 | Nativity of Mary | Drink |

| September 21 | Matthew's | Drink |

| September 25 | Firmin's | Drink |

| October 28 | Simon's and Jude's | Drink |

| November 10 <sic> |

Martin's | Not moratum but drink |

| November 30 | Andrew's | Not moratum but drink |

| December 11 | Fuscian's, Victorius' and Gentian's |

Moratum |

| December 21 | Thomas' | Drink |

| Beginning of Lent | Drink | |

| Maundy Thursday | Drink | |

| Holy Saturday | Drink | |

| Easter Sunday | Moratum | |

| Wine allowance through the whole week | ||

| In the midst of Easter, on Abbot's Week, on Ascension of the Lord, on Pentecost |

Drink | |

| July 11 | St. Benedict the Abbot's | Drink |

<I.3>

<EXTRA ALLOWANCES[64] OF PREBENDS>

The Distribution of Extras[65]

Now these are the thirteen days on which, for the love of God

and of the saints of those days, an extra allowance is to be given

to the prebends outside their own stipend, if that is not enough

or sufficiently satisfying. The extra is one loaf between two of

the vassals,[66]

of the size which is made thirty to a modius, and

to each vassal a half pound of some kind of vegetable, and to

each a full beaker, whether it should be from out of the wine

are: the Lord's Nativity, on Holy Epiphany, the Mass of Lady

Balthilda[68] (and for that day the allowance is drawn from the

ministry of the chamberlain[69] ), Purification of St. Mary, on

Sunday the beginning of Lent, on Maundy Thursday, on

Holy Easter, Ascension of the Lord, Pentecost, Mass of St. John

the Baptist, of St. Peter, of St. Martin, of St. Andrew.

Vasalli is evidently used here as genus for species provendarii; but

above (367 l. 8) the casa vassallorum, within the compound, is listed as

having two prebends in service—a suggestion that the casa was a hospice

for visiting beneficiaries holding their beneficium from the abbot. At the

end of section 11 Adalhard lists in order: (1) famuli nostri vel matricularii,

(2) fratres, (3) vasalli, (4) ospites, (5) pulsantes vel scolarii, (6) singuli

provendarii.

Feasts on Which

Work on the Domain is Omitted

Furthermore, in like fashion these are the days on which men

are freed from work on the domain, except as it pertains to the

preparation of food: Nativity of the Lord, St. Stephen's,

St. John's, Innocent's Day, Octave of the Lord, on Holy

Epiphany, Mass of Lady Balthilda, Purification of St. Mary,

on the first Monday in Lent (stipulated in order that the laity

may have time to renew their confessions), Maundy Thursday,

Good Friday, Holy Saturday, Wednesday in Easter, the three

days of Rogations, the Ascension of the Lord, St. John the

Baptist's, St. Peter's, St. Marcellinus',[70]

St. Firmin's,[71]

St. Martin's, St. Andrew's, Christmas Eve, and the Four

Seasons days.

<I.4>

<THE VESTING OF PREBENDS OR NOVICES>[72]

These are what should be given to our aforesaid clerical canons

who have the special title of "knockers"[73]

: in clothing, two

white tunics and a third of another color and four hose, two

pairs of breeches, two felt slippers, four shoes with new soles

costing seven pence at the cobbler's, two gloves, two mufflers.

These they receive every year, but a cope of serge and fur and a

mantle or bedcloth, or a blanket, in the third year. All these

should be taken from the clothing which the brothers return

when they receive new.[74]

And they should select from the stock

those garments which they think are most useful to them. The

other cowled garment[75]

—the tunic[76]

or the cowl of serge from

which the tunic can be made—will be issued at the discretion

of the prior.

Verhulst and Semmler, 1962, 254; see I, 341, and 337ff. The

Council of 816 considered the clothes allowance (Corp. Cons. Mon. I,

462; cf. p. 446).

Verhulst and Semmler, 1962, 114, 119, 251, 254, 256, 259-62, 264,

266; Lesne, 1929, 446, 453; see I, 341; II, 195, 208. Provendarii -

praebendae < praebere: "terrena subsidia (debent praelati) diligenter illis

praebere."—Regula s. Chrodegangi, c. lv; "victus . . . quae iure ab

abbatissis praeberi debuerant."—Conc. Turon. 813, c. x. Hence, "permanent

domestic personnel."

<II>

<THE POORHOUSE>[77]

We have stipulated that loaves be given out every day at the

poorhouse—forty-five made from three and a half pounds of

maslin and five made of wheat or spelt such as the vassals

receive, making a total of fifty loaves. These loaves are to be

distributed as follows: twelve paupers who are staying there

overnight should each receive his own loaf; and the next morning

each should receive a half loaf for the road.[78]

Then the two

hospitalers who have been serving there should each receive one

loaf from the aforesaid stock. The five loaves of wheat bread ought

to be distributed among the migrant clergy, who are admitted

to the refectory,[79]

for the road, and among the infirm who are

cared for at the poorhouse. However, we leave this distribution

of bread to the discretion of the hospitaler for this manifest

reason: if a greater number of paupers or those who are more

or less needy, such as the weak, or very small boys who eat little,

should appear, then he should decide how much is needed. But

if it should happen at another time that fewer paupers came,

then the hospitaler and his master, the senior porter,[80]

should

determine, after considering all factors, how much less than the

prescribed number should be dispensed because few came. In

that way what was left over may be dispensed at another time

when more may come.

But for the other poor, who come and go on the same day,

it is customary to give out a quarter of a loaf, or, as we have

just said, the amount that the hospitaler foresees to be needed to

take care of a greater or lesser number or need. The food to

accompany the bread[81]

should be allotted according to custom.

With regard to drink, there should be given out each day a

half modius of beer, that is, eight sesters. Of these, four sesters

are divided among those aforesaid twelve paupers, so that each

will receive two beakers. Then from the other four sesters is

given one beaker to each of the clerical brothers who wash the

feet[82]

and one beaker to Willeramnus the servitor. We leave to

the discretion of the hospitaler the method of dividing any

residue among the infirm or the other paupers. But the matter

of wine shall be in the discretion of the prior.

However, the senior porter ought to anticipate the needs of

the infirm in order to be able to supply either food or drink

which the hospitaler lacks to meet the need of the infirm.[83]

And if it should happen that pilgrims come from distant lands

in excess of the stipulated numbers, the porter[84]

should provide

for them the things that are necessary in such a way that the

supplies which are stored to meet the daily requirements are

not diminished.

Also we add to the foods of the poor as accompaniment to

bread thirty standard rations in the category of cheese and bacon

and thirty modii of vegetables, a fifth part of the tithe of eels[85]

which the porter receives from the cellarer, or of the new cheese

which is due in payment from the ten sheepfolds,[86]

together with

that which is given in tithe from the villas of the domain, as well

as every fifth part of the tithe of cattle, that is in calves, in sheep,

or anything which is given to the porter from the flocks,

including horses.

Furthermore, beyond the aforesaid we have arranged to give

directly through the agency of the senior porter to the hospitaler

a fifth part of all money whatsoever that may come to the gate.[87]

Of this money we have desired to create such a method of

distribution that not less than four pence should be given out

each day. And if the amount from that fifth should be less than

sufficient for making that daily distribution, the abbot, if he

withheld if it should rise above that amount.

According to custom the porter should provide firewood for

the poor or other things which are not recorded here, such as

the kettle or dishes and other things that are in the quarters.[88]

Of those things which come to the gate, all the aforesaid rations

should be given out according to the method of distribution of

the supplement of money, just as it is recorded above.

Furthermore, the hospitaler should receive from the

chamberlain the old garments and footwear of the brothers for

distribution to the poor according to custom.[89]

Therefore we beg all those to whom the office in this

monastery should be assigned that they order their decisions in

the generosity and almsgiving of God rather than in the example

of our parsimony, since each will be rewarded according to his

own standard.

hospitium (l. 4) or ospitalis (l. 5) pauperum. Verhulst and Semmler,

1962, 105, 255-56, 264-66; Lesne, 1925, 247; see II, 144-53.

Council of 816, XXI and XXII (Corp. Cons. Mon., I, 463); Verhulst

and Semmler, 1962, 260. Guérard, 197, and Lohier-Laporte, 120,

equate the Carolingian sester with 4.25 liters.

Lesne, "La dime des biens ecclésiastiques au ixe et xe siècles,"

Revue d'histoire ecclésiastique XIII (1912), 479 n. 3.

<III>

<THE GRAIN SUPPLY>[90]

The disposition or amount of grain or of bread: What kind or

where from or how much is due to come to the monastery each

year, or in what fashion the bread-warden[91]

ought to dispense it:

It is our wish that every year there should arrive 750 corbi[92]

of

well-winnowed and husked spelt, each corbus having twelve modii,

well compared and standardized to the new modius which the

Lord Emperor has set.[93]

That grain supply should come from

those villas which the provost has particularly in his charge,[94]

and, if it should be necessary, from all of them, but if not then

from those which he shall have agreed on with the abbot. We

have purposely set that amount so that for every day of the

year, 365 of them, there will always be two corbi, which make

in all 730 corbi. Then we have taken pains to add twenty so that

there may in time be a surplus rather than a shortage. And

although that grain supply may sometimes be better, sometimes

worse, and may occasionally yield more flour and occasionally

less, yet we hope by calculating averages that from those two

corbi we may always get ten modii.[95]

Therefore if each modius

thirty loaves. . .[96]

300, then we have made sure that at all times

we will have in the monastery not less than 300 and always

something more between the leftover and the incoming. Yet

though we would at present not number more than 350 members,

nevertheless we want to arrange as if we were at all times about

400, sometimes less, sometimes more. In this way, when we are

less than 400 a surplus will accumulate. Then the bread can be

distributed more generously when we are more than 400. Yet

it has rarely happened that we have that larger number since it

most often happens that we number many fewer than 400.[97]

Therefore we should add four modii a day of flour which

comes from the mills and make 120 loaves; add the amounts

together and there are 420 loaves. Note that we have not only

loaves every day, which are even more rarely needed. But

because we desire all our substance which is dispensed through our

ministers always to be larger, so that there may be surplus rather

than shortage, we now add still another modius to the amount

which comes from the mills; and that makes 450 loaves daily

from the fifteen mills. According to this plan, by adding the

amount for each day we get the annual total of 5475 modii.

Also we should add twenty-five from those mills and that makes

5500. Of these, 3650 should come from spelt, with a remainder

of 1850 from the mills.[98] Now because, as we have already

remarked, we want to have a surplus more often than a deficit,

for that reason we arranged first to add twenty corbi and then

daily more loaves in addition to the 400 regularly rationed, and

finally twenty-five modii, even though, as was said before, we

are apt to number less than 400 more often than very much

above 400. And because cattle, swine, different birds, dogs and

even horses are to be fed at the mill itself, we should then add

from the mills themselves 150 modii, making in all 2000 modii

which should come from the mills.[99] Meanwhile these

stipulations as set down should be observed until we can

consider together whether it may be necessary to add or

subtract anything.

Nevertheless, as a precaution we request the warden of the

loaves to pay very close attention in every detail to anything

that can be learned from the distribution or the accounting by

days, weeks, or months of the whole year, to the end that when

the time for change[100]

comes he will be ready to recount to us

how he has administered the current year. And in order that he

may the more easily know, he should first set aside those

allowances which are routinely held and distributed in equal

amounts through rationing. That number is always the same,

unless through some accident there should be a need for fewer

rations; for there is never a need for more. Then he should

calculate the brothers' bread, according to whether it is to be

eaten once or twice in the day.[101]

Let him always set apart what

is deputed for their needs. Let him figure how much is needed

for the period when it is regularly eaten once a day, and how

much when twice a day, and how much in one week in either

case—how much in a week when the lesser amount and when

the greater. We opine that he can thus very closely approximate

what quantity of bread or modii he should have to furnish for

their needs. In that number are to be figured all who receive

brothers' bread except those guests who do not receive it every

day. Moreover, the warden should avoid baking so much of the

brothers' bread that the leftovers get too hard. However, if he

should do so during the period when he is trying to establish

the correct number, that bread is to be taken away and other

bread substituted for it. But because, as we have said, we

sometimes eat once a day and sometimes twice and we are now

many, now few, and we can never limit ourselves to exactly the

number we ought to be, if with the help of God he can invent

some other better method of effecting the desired end, he should

do so. The same applies to provisions for our vassals, and the

same also for those at the gate, the number of which cannot be

set. If he shall have begun to calculate by the method we have

spoken of above—by days, by weeks, by months; the seasons

when he distributes least, when average, when most—we think

that he surely can determine how he will be able to get through

the whole year. So for the novices, the scholars, the rest of the

clerks, whether our lay brothers or the externals,[102]

he can easily

formulate the procedure for caring for them.

Also we admonish him to be sure to keep in mind how that

bread is to be distributed which is not given in equal amount to

all, but more to some and less to others. In this operation he

needs to determine with each measure of loaves how many of

the large, medium, or small can be made from one modius; and

we hope that by so doing everything will be quite clear to him.

Now as far as has been in our power, we hope that we have

invented an effective means whereby we may be able in the

future to handle the grain supply which should arrive at the

monastery under the categories which we have stipulated above,

not that we wish to solidify such a procedure permanently, but

in order that we can learn the right way by making a start. The

rations are those of, first, our servants and working dependents,[103]

who always should have the same amount; second, of the

brothers; third, of the vassals; fourth, of the guests; fifth, of

the novices or scholars; sixth, of each of the prebends here and

there. Unfortunately, of these last, as we have said, we cannot

stipulate a number which would always hold stable.

WHAT WE WANT AS THE PROGRAM FOR MILLS

OR MALTHOUSES

First, that a manse and six bonuaria[104]

of land should be given

to each miller, because we wish him to have the wherewithal

which allows him to carry out the orders laid on him and to see

to it that the millings are properly protected. That is, he should

have oxen and ready implements with which to work, whereby

he and all his helpers can live, feed the swine, geese, and

chickens, maintain the mill and acquire all the timbers needed

to keep it in repair, renovate the weir, tend to the millstones and

be capable of supplying all the materials and labor which are

needed for maintenance and operation there.[105]

And therefore

we do not want him to do any other service—not with cart nor

horse nor manual labor nor plowing nor seeding nor gleaning

the fields or meadows, nor by making mash or hops nor by

trimming trees, nor should he do anything else needed on the

domain aside from what is needed to take care of himself and

his mill.[106]

But the swine, geese, and chickens which he ought to

fatten at his mill, let him feed from his own meal. Let him also

gather the eggs. And, as we have said, let him tend to procuring

those things which he needs to make the mill work or which the

mill ought to produce. But what we have stated above[107]

—that

for our use—we have not stated with a view to removing that

other production from that granary, but in order that the miller

should try to demonstrate in the course of a year whether it be

necessary to add or to subtract from the amount. He should be

in a position to produce in the course of a whole year such a

number as is conformable with the number of prebends and with

the variety of operations carried on in the monastery each year,

which are governed by the vintages, the gardens, the fields, and

such like.

We also desire that, in the presence of the millers, the older

modii be made to conform exactly in every way with the new

modius. Then, however many new modii they find are equivalent

to the old ones, they should in the future pay as their due,

whether of flour or grain, according to these new modii, so that

the tally agrees.[108]

And we desire that every one of the millers should keep his

plant in operational order with six wheels ready to work. But

if anyone does not wish to have six, but only half that number,

that is, three wheels, he should not have more than half of the

land that attaches to that millstead. That is, he should hold three

bonuarias, and his associate the other three. Then between those

two they should render the full milling and perform the full

service required of that one mill, with regard to milling or the

millpond or the bridge or all other duties as they are assigned

to each separate mill.[109]

For measurement of bonuarium see L. Musset's investigation in

Melanges L. Halphen, Paris, 1951, 535-41. Possibly, like the "acre," an

amount to be plowed by a yoke of oxen in one day.

Adalhard's investment of milling will illustrate the monastic contributions

to growth of power, described, for instance, by R. J. Forbes in

The History of Technology II (Oxford, 1956), 606-11. "Adalhard distinguishes

two categories of obligations of millers: the moltura, on the

one hand, rendered equally by the phrases ea quae ei rubentus perficere

and ea quae de molino debent exire; the servitium, on the other hand, or

ea quae molino necessi est facere, among which are included the upkeep

of the mill. . . and the delivery of swine, geese, and chickens fattened at

the mill on behalf of the abbey, as well as the delivery of eggs, and

possibly other duties" (Verhulst and Semmler, 1962, 245).

Evidently a portion of this section has disappeared, since the malt-houses

mentioned in the rubric are not treated. Lesne, 1925, 400.

Verhulst and Semmler, 1962, 108, 110, 241-42, 244-45, 247, 253,

255, 259, 266; Lesne, 1910, 17-21; see I, 333; II, 215-48; 254.

The corbus seems to have varied from 10 to 14 modii depending

upon the crop; see Du Cange, Niermeyer. The modius (which Adalhard

as regularly writes modium) is, roughly, a peck.

See especially Corp. Cons. Mon. I, 375 n. 7; and I, 52 n. 19; and the

translation below of Corp. Cons. Mon. I, 379, p. 108. Charlemagne

decreed the new measure before A.D. 794 (text Mon. Germ. Hist. Concilia

II, 166; Capitula I, p. 104; etc.). The standard was on deposit in the

palace at Aachen. But in spite of the royal decree, the measure was not

uniform in the kingdom of the Franks. Adalhard seems to refer to the

repetition by Louis I of Charlemagne's decree.

The editors, Verhulst and Semmler, have not questioned this

number: "3650 muids étaient fournis par les villae du prévôt" (247,

n. 215). They thus equate it with the statement above, "villas which

the provost has particularly in his charge." But 750 (corbi) × 5 (modii)

= 3750.

tempus mutationis. "Fratres vero qui in diversis ministeriis foris

occupati fuerant medio augusto cum mutatio facienda erit sive de cellis

seu de villis ad coenobium redeant."—Statuta Murbacensia, × (Corp.

Cons. Mon. I, 445).

See above, p. 104 and I, 333; Benedicti regula, chap. 41, ed. Hanslik,

1960, 102-104; ed. McCann, 1952, 98; ed. Steidle, 1952, 238-39; Corp.

Cons. Mon. I, 114, 133, 335, 474ff; Verhulst and Semmler, 1962, 256

n. 262.

<IV>

<THIS IS THE MANAGEMENT OF

THE GARDENS>[110]

In order that the brothers that ought to work them[111]

can do so

without molestation or any unseemly disturbance there while

they fulfill the duties committed to them for the common good,

we have decreed that the mayors[112]

of the following villas should

build whatever accommodations are needed there, and erect and

mend fences to the extent that they should be necessary: at the

first door, which is next to the stockyard, the mayor of Wagny

and Chipilly; at the second, of Ville-sous-Corbie; at the third,

of Aubigny and Cérisy-Gailly; at the fourth, of Vaire-sous-Corbie

and Thésy-Glimont. And they should each give the same

amount—each to the garden assigned to him—every third year

one plow, a yoke with rope and ties when it shall be necessary,

and in the fourth year a barrow for cultivating the garden. The

effective date is always the Mass of St. Marcellinus.[113]

And when

the time comes when it is necessary to clean the weeds out of

the fields (that is, from the middle of April up to the middle of

October), let each one of these mayors without any suggestion

of negligence or slovenliness of any kind appear every twenty

days before the brothers' gardener to whom he should render

assistance, to see and ask when he should need to assign weeders

to that garden. Then after the various kinds of leek (porri et

garlics, and the onions, the mayors should weed them as much

as and whenever necessary, just as has been stated.[115] And

whenever the workers gather for that weeding, the mayor

himself in his own person or the dean—one of those two—

should be there to see to it in every detail that the workers

complete their work conscientiously and efficiently. The

gardeners should receive carts from the shed every year

according to custom. They ought to receive all iron tools from

the chamberlain,[116] who should supervise the smiths according

to the custom of the community. If any of the tools should be

broken, let the gardener show them to the chamberlain[117] and

let him have them repaired or give out another metal appliance

and take in the broken one. Furthermore, those tools must then

be repaired by the chamberlain in whatever way may be

necessary. And for cultivating the field or for carrying out any

other needs, let each one have six trenchers[118] , two spades, three

hatchets, one pick-axe, two sledges, large and small, one pruning-knife[119]

, one gulbium,[120] two sickles, one scythe, two trunci,[121] one

coulter, one scerum,[122] and other instruments kept in the

chamberlain's office, as are winnowing fans,[123] casting shovels[124] or

other things of this sort. Whenever old equipment breaks down,

the gardener should tell the abbot. The abbot will advise him

about obtaining replacements.

We have also arranged to give the brothers one hundred

loaves as periodic rations for men who accompany them. These

men are to clear the fields in autumn and to assist the brothers

in planting the fields in spring, as well as to weed the seedlings

in summer as each brother gardener shall deem necessary. The

brother who provides the brothers' bread should give out those

loaves, not all at once but according to the gardener's needs.

In this way the dispenser should deliver bread to him as he

needs it until the quota has been filled. Likewise one modius of