The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| III. |

| III. |

| I. | APPENDIX I |

| II. |

| III. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

I. APPENDIX I

A CATALOGUE OF INSCRIPTIONS

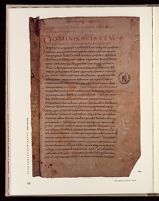

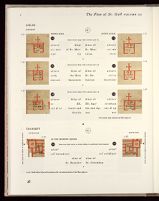

523. CALCULUS VICTORII AQUITANI. MODEL ALPHABET. ABOUT 836

FRONTISPIECE: FIGURE 523 PAGE XXXIV

MODEL ALPHABET (CA. 836)

BERNE, BURGERBIBLIOTHEK MS 250 fol. IIV

Employed chiefly for titling of manuscripts, these monumental capitals, descendants of

letter forms used in Roman inscriptions, are executed with utmost precision in a style

established in use during Charlemagne's reign. On the tracing of the Calculus manuscript

to antecdents in Fulda, and the alphabet exemplar to a model made by the scribe

Bertcaudus, see Bischoff, cat. no. 385a, p. 219, in the catalogue Charlemagne, Aix-la

Chapelle, 1965.

A CATALOGUE OF

THE EXPLANATORY TITLES

OF THE PLAN OF ST. GALL

PREFACE

THE explanatory titles of the Plan of St. Gall are discussed in widely scattered places in the main body of this

work, in the specific contexts of the buildings with which they are associated, as well as in the broad range of

architectural and historical problems they raise. In such fragmentation, the inscriptions cannot be studied as a

whole and coherent body of texts. Yet, the explicit content and cultural implications of these inscriptions make

their ready accessibility not only desirable, but even imperative.

Of the 340 separate annotations on the Plan of St. Gall, more than 300 have no other purpose than to explain

specifically, and often in highly technical terms, the uses and functions of the 40-odd buildings which comprise

the monastery, the assigned use of individual rooms in these buildings, and, as well, the nature and function of

each piece of furniture or equipment installed in these rooms. The superior intellect of its originator and his deep

concern with detail make the Plan a storehouse of lexicographical information furnishing the student with an

opportunity for linguistic exegesis that has no equivalent in any other historical source on medieval art and

architecture. The words elucidate the drawing, the drawing elucidates the words. They combine to reveal in

intimate detail whatever one would want to learn about the buildings of the Plan, and explicate, with an unparalleled

thoroughness, whatever is required—in architectural, liturgical, educational, medical, technological

and agricultural terms—to support the purposes and the high quality of life within the confines of a self-sustaining

religious community.

It is in view of the profound relevance this material has for the history of medieval architecture, both monastic

and vernacular, as well as for the history of medieval economy and for medieval life in general, that we thought

it imperative to make all this explanatory matter available in a coherent and easily identifiable form for the benefit

of those who are interested in the Latinity of the Plan, its linguistic and paleographic details, and who, in this

manner, inter alia, will also be enabled to critically evaluate our success or failure to interpret this material

correctly.

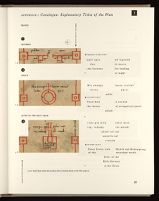

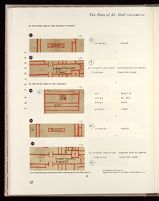

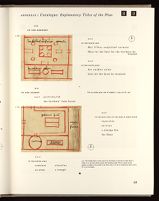

To further these ends we have presented in the Catalogue that follows, in juxtaposition: first, a reproduction of

each inscription as it appears on the Plan (for legibility enlarged to one and one-half times the size of the original);

permits; and third, our interpretation of the texts rendered in English. While the inscriptions, seen here in their

architectural ambient, are able to furnish a unique and intimate view of the Plan, this Catalogue is not meant to

substitute for a facsimile of the entire document, an artifact already admirably executed by the firm of E. LöpfeBenz

of Rorschach.[1]

It is no small presumption to dissect an entire document into graphic components in order to scrutinize its

details. At risk is the coherence of the whole artifact. If we have avoided the worst of that hazard, it owes to the

patience and skill of Ernest Born who, from the viewpoint of book design, found this Catalogue to be the most

complex, time-consuming, and esthetically challenging part of the task to which he has devoted long attention.

The general historical implications of the explanatory titles of the Plan have been discussed in earlier chapters.[2]

In the present context we will make a few remarks about the Latinity of these texts, the manner in which they

are visually displayed, and some of their primary paleographical characteristics.

LATINITY

The Latin of the titles is lucid, as even a peremptory reading of this catalogue reveals. It makes use of a judicious and

sophisticated alternation of prose and verse. With a few exceptions (discussed below), verses—hexameters and distychs—

are employed to designate the general purpose of a building, whereas prose is used for their component parts and furnishings[3]

.

PROSE

The prose is logical and unambiguous, and the diction conveys meaning with great precision. This holds true even for the

letter of transmission which, although without any internal flaw, has caused some consternation among scholars. Closer

inspection has shown that whatever controversies arose in connection with this text were due not to any inherent ambiguities

in its style or composition, but rather to linguistic misconceptions of its modern interpreters. The note has the form of a

regular letter, naming its receiver, addressing him directly, revealing that the Plan was made upon the request of its receiver,

and that it needed for a particular purpose.[4]

Its only truly tantalizing feature is that it lacks a signature. There is no cause

to blame the author for this omission. The Plan of St. Gall was not made for posterity, but for the benefit of an abbot,

who had no trouble in identifying the high person who furnished him with this scheme.

In the entire body of inscriptions only seven words have given rise to conflicting interpretations: the terms exemplata and

officina (in the letter of transmission), uacatio (in the Outer School), seruitium (in the House for Servants from Outlying

Estates), sauina (in the Monks' Cloister), toregma (in the Monks' Refectory and the House for Distinguished Guests), and

testu (in the Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers and in the Outer School). In four of these cases a search for contemporary

parallels has shown that their meaning is unequivocal. Exemplata means "copied," not "by way of example"

as had been proposed.[5]

Officina cannot be restricted to the meaning "workshop" but refers to all of the buildings of a

monastic settlement.[6]

Uacatio means "time vacated from other obligations for the purpose of learning" and cannot be

interpreted to mean "recreation" as its modern derivative "vacation" has tempted some to suggest.[7]

Seruitium are the

services due an overlord by his tenants and serfs, and is a term applicable to both secular and ecclesiastical lords.[8]

Sauina

is the classical and medieval designation for the savin plant. Its meaning is clear although we are at some difficulty in explaining

fully the reasons that this plant was given a place of such honor in the Monks' Cloister.[9]

Toregma, in the previous

literature on the Plan varyingly interpreted as "cupboard," "a vessel for washing hands," "a chair or cushioned seat" or

stretched even by its medieval users beyond the limits of propriety,[10] is used on the Plan of St. Gall as a designation

for "cupboard," as must be inferred from the shape of the object to which this term refers (Monks' Refectory, Abbot's

House, House for Distinguished Guests). We are aware of only one other literary source (Ruodlieb), in which the term is

used in this sense. Testu in the literature on the Plan, consistently misread as testudo ("turtle shell"), means "protective

shell" or "cover." I have not been able to find any contemporary parallels, but the architectural context in which it appears

on the Plan suggests that its meaning is "louver", i.e., a protective covering over an opening in the roof that serves as

smoke escape and as light inlet.[11]

The term formula requires some explanation. The shape and size of the objects into which this word is inscribed (long,

narrow rectangles in the crossing and transept of the Church) precludes that it be interpreted as "lectern" as has been

proposed[12]

(the scribe's term for lectern is analogium). Among the numerous references to forma and formula quoted by

Du Cange and Niermeyer and indexed in source books such as Lehmann-Brockhaus (1935, 1938, 1955-1960) or the five

volumes of the Corpus Consuetudinum Monasticarum (1963-1968) there is only one instance, a rather late one at that, where

formula has been interpreted as "lectern"—incorrectly in my opinion.[13]

The history of the term is interesting. In Classical

Latin forma and its diminutive formula served to denote such concepts as "norm," "rule," "guiding principle," or "covenant,"

but also stood for "matrix," "pattern," or "mould."[14]

It is in the former sense that the term is used by St. Benedict

in an often-quoted passage in which he defines the human and intellectual qualities which an abbot must possess:

In doctrina sua namque abbas apostolicam debet illam semper formam seruare, in qua dicit: "Argue, obserua, increpa."

"For the abbot in his teaching ought always to observe the rule of the apostle, wherein he says: `Reprove, persuade,

rebuke.' "[15]

The term retained this meaning throughout the Middle Ages, but in addition generated a distinctly different variant when

it became a designation for a liturgical piece of furniture that, depending on context, may be varyingly translated as "church

bench," as "kneeling-bench" (prie-Dieu) or as "choir-stalls"—a meaning that I suppose evolved from its secondary

classical usage "matrix" or "mould." The shape and size of the objects into which the word formula is inscribed on the

Plan suggests that it was here used in the sense of "bench" (for sitting). Yet an even furtive review of its use in Merovingian,

Carolingian and later medieval sources discloses that it served even more frequently as a designation for a liturgical

contrivance that in modern French, English and German is referred to as "prie-Dieu," "kneeling bench," and

"Betstuhl," viz., a piece of furniture that supports the body when kneeling and may also be used as prop during the

deep liturgical inclinations in which the monks engage in the more sacred phases of their religious service. These prayer-supports

could either be set up separately in front of the choir benches or they could be physically attached to them (as

in the elaborate choir stalls of the high medieval abbey and cathedral churches) which explains the use of forma and formula

for either one (i.e., a bench for sitting) or the other (i.e., a support for kneeling and liturgical inclination) or the combination

of both in a fully developed choir stall (i.e., a piece of furniture, in which a solid row of prayer-supports is firmly

attached to a range of benches with hinged seats and a high-rising back.

A good example for the use of formula in the sense of bench is in the Vita sanctae Geretrudis, in a passage referring to

an event that occurred in 783 A.D.:

Haec audiens peregrina. . .eam duxit in ecclesiam beatae Mariae virginis et posuit eam ante formulam, ubi Geretrudis sancta

sedere solebat.

"In hearing this the woman on pilgrimage. . .conducted her [i.e., a young girl who had a vision of St. Gertrude] into the

church of our blessed virgin Mary and placed her before the bench where Saint Gertrude used to be seated."[16]

Unmistakably used in the sense of "support for kneeling in prayer" is the term in the famous petition (probably drafted

by Eigil, later abbot of Fulda) which the monks of Fulda submitted first to Charlemagne in 812, and again to Louis

the Pious in 817:

Quod infirmorum maior cura sit et miseratio senum videlicet et debilium neque penuria victus affligantur neque vestitus paupertate

conterantur et nec ineptiis aliquibus vexentur, ita ut nec baculum eis pro sustentatione fere liceat nec ad inclinatorium, quod nos

formula genua flectere.

"That special care be taken of the sick and mercy extended to the old and feeble so that they may not be afflicted by a

shortage of food nor struck by poverty in clothing nor subjected to any other unsuitable vexations such as being forbidden

to carry a staff for their support, or linger and cling to the inclinatorium, which we call formula, because the blind and

and the lame cannot move about without a staff nor can the decrepit bend his knees without a formula."[17]

The passage is interesting because it discloses that the prie-Dieu although clearly known, was not in general use at that

period (at least not so far as the Abbey of Fulda is concerned) since the monks in their petition speak of them as a privilege

to be made available to the old and feeble. The author of the Plan of St. Gall, as already stated, used formula in

connection with an object so shaped that it can only be interpreted as "bench," and in terms of literal visual exegesis

this is the way it should be interpreted. But in designating this object by the term formula (more frequently used in the

sense of prie-Dieu than in the sense of "bench" in contemporary sources) he may have wanted to imply that these benches,

if desired, could be furnished with a range of lean-to's to support the monks when kneeling or bending.

Special attention must be drawn to the use of the word domus, since confusion about the meaning of this term among

earlier students of the Plan has had an adverse effect upon the identification of the building type in which the workmen,

the serfs, and the animals are housed. We have discussed this matter at length in its proper place in the second volume,[18]

and therefore confine ourselves here to simply re-emphasizing that on the Plan of St. Gall the word domus is

used not as a designation for the whole of the house, but (as its qualifying adjectives disclose) for an important spatial

function of the building: its "common living room" (domus communis) or "principal room" (domus ipsa) where its components

gather around the open central fireplace, as distinguished from the peripheral rooms which serve more specialized

occupants such as sleeping or the stabling of livestock. In only one instance, in the hexameter that defines the purpose of

the House for Goats and Goatherds, does the term domus refer to the entire structure.[19]

The term pisale is on the Plan of St. Gall exclusively used as a designation for rooms that are heated by warm air generated

in a subterranean firing chamber and channeled into the interior by heat ducts installed under the floor (Monks'

Warming Room, as well as the warming rooms of the Novitiate and the Infirmary).[20]

This is in full conformity with its

classical root pensilis, an adjective formed from pendere (to hang, to be suspended) and in architecture employed as a

technical term for structures that do not rest exclusively on their own foundations, but are raised upon columns, pillars,

arches or vaults as was the case with rooms in Roman houses or baths that were heated by hypocausts.[21]

The term changed

its meaning later on, when it produced French poêle (stove) and Middle High German pisel, phiesel and phiselgadem (a

heatable room).[22]

Rooms with corner fireplaces are referred to as caminatae, (prime example: House for Distinguished

Guests).[23]

The term caminata, however, is also used for the corner fireplaces themselves (Abbot's House).[24]

The word solarium appears only once on the Plan (Abbot's House) in a textual and architectural context, that makes it

unequivocably clear that it refers to the upper level of a masonry building whose rooms gave access to the rays of the sun

by means of windows.[25]

Pistrinum is exclusively used in the sense of "bakery," never in its alternate classical meaning of

"mill."[26]

This again is in complete conformity with common contemporary parlance. The term porticus, however, has

two distinctly different meanings. In the Monks' Cloister,[27]

the Cloister for the Novices[28]

and the Cloister for the Sick,[29]

it is used in the traditional classical sense as designation for a colonnaded gallery or porch, giving access to, or being

attached to some other (usually larger) structure.[30]

In this sense it is also used for the two sunlit porches of the Abbot's

House (porticus arcubus lucida).[31]

But in one of the most important explanatory titles of the Church of the Plan porticus

but forms an integral part of its spatial composition. The extension of meaning from "porch" to "aisle" needs hardly

any comment, since the morphology and function of a galleried porch are virtually identical with those of the aisles of a

basilican church, the only difference being that in one case the gallery opens outward, in the other inward. Yet despite

these similarities the term does not appear to have gained great popularity as a designation for "aisle." Hrabanus Maurus

(ca. 776-856) uses it in this sense in his verse description of the Abbey Church of Fulda (dedicated in 818) where, with

a verbal discrimination rare in medieval poetry, clear distinction is made between the northern and the southern aisle of

the church (in porticu septemtrionali—in porticu meridiana) the transept (transversa domus), the eastern apse (in abside orientali),

the western apse (in abside occidentali), and the crypt (in crypta).[34] But this is the only Carolingian occurrence of this use

of the term, outside the Plan of St. Gall, that is known to me. The pre-Carolingian biographies compiled in the Liber

Pontificalis do not employ it in this sense[35] and the bibliographical sources published in the Scriptores rerum Merovingicarum

where the term appears in numerous places, contains not a single case where porticus can be identified unequivocably, as

a synonym for "aisle."[36] Even in post-Carolingian times the term is used only sparingly in this sense. It crops up in the

Chronicle of Montecassino, where we are told that Abbot Desiderius raised "the walls of the two aisles [of the new monastery

church he started to rebuild in 1066] up to a height of 15 cubits" (porticus etiam utriusque parietes in altitudine cubitorum

xv subrigens);[37] and it occurs in the Life of St. Dunstan, written by William of Malmsbury about 1126 in a passage, where

the Saint is said to have added alas vel porticus to an older church which he wished to widen.[38] Yet these are relatively

isolated occurrences. The full history of the term would obviously require a more systematical study than is possible in this

context; but it is surely indicative that a quick perusal of the passages referred to in the indices of the source collections

published by Schlosser, Mortet-Deschamps, and Lehmann-Brockhaus, leave little doubt that in an overwhelming majority

of cases porticus is used in its traditional classical sense as an equivalent for "colonnaded gallery" or "porch" and in only

a small number of cases as a designation for "aisle."[39]

The term claustrum occurs twice on the Plan, once in the Monks' Cloister ("quattuor semitae p transuersum claustri",

"four paths crossing the cloister at right angles") and once in the cloister of the Novices ("hoc claustro oblati pulsantibus

adsociantur", "in this cloister the oblates and those who are knocking live together").[40]

The etymological root of claustrum is found in the word claudere, "to shut" or "to lock."[41]

In Classical Latin, claustrum

stood for "lock", "bar", or "bolt"; more figuratively for "bounds" and "confines"; in military language for "barricade",

"bulwark", and other defensive enclosures.[42]

St. Benedict used the term in the sense of "confines" (claustra monasterii

egredi)[43]

—a meaning which it retained for centuries along with all the other connotations it subsequently acquired. St.

Gregory used it in the sense of "prison" (quod etiam retentus corpora ipsa jam carnis claustra contemplatione transebat), or

"confines"[44]

, Isidore of Seville more concretely for "folding doors" (valvae).[45]

When precisely in history the term claustrum became the designation for an architectural entity consisting of an open

in the Life of Bishop Hrodbert of Salzburg (d. ca. 710) where claustrum may have that connotation (although one would

like the phrase to be a little more specific to feel entirely sure of this interpretation): "claustra cum ceteris habitaculis ad

ecclesiasticorum virorum pertinentibus . . . construxit.[46]

In Carolingian sources claustrum is used in a variety of ways: (1) as a designation for the open inner court and its surrounding

porches, (2) as a designation for the porches alone, (3) as a designation for yard and porches, plus the entire

frame of buildings ranged peripherally around them, and (4) as pars pro toto for the whole of the monastic settlement.

On the Plan of St. Gall the cloister walks or cloister porches, as already mentioned, are individually referred to by the

term porticus. The word claustrum appears in titles that are inscribed into the open yard between these porches, and may

be interpreted—depending on where one places the accent—as either referring to the open yard alone (since the paths

that cross each other at right angles are physically confined to that space) or to the open yard plus its enclosing porches

(since the paths emerge from these porches). It is in this latter sense that the word is used in Hildemar's commentary

(ca. 845 A.D.) to the Rule of St. Benedict where it is said, "Dicunt multi, quia claustra monasterii centum pedes debent haberi

in omni parte minus non" ("It is generally held that a cloister should be one hundred feet square, and no less."[47]

These

dimensions could not possibly refer to the whole of the claustral complex, since it would be impossible to fit its buildings

into an area a hundred feet square.[48]

Another clear case of the use of claustrum to mean the cloister yard and its surrounding frame of porches is in Hariulf's

Chronicon Centulense (1088 A.D.) in a passage describing the cloister of the monastery built by Abbot Angilbert between

790 and 799. In the same narrative the cloister walks are referred to as tectus:

Claustrum vero monachorum triangulum factum est, videlicet a a sancto Richario usque ad sanctam Mariam, tectus unus; a

sancta Maria usque ad sanctum Benedictum tectus unus; itemque a sancto Benedicto usque ad sanctum Richarium tectus unus.[49]

"The cloister of the monks, however, he built in the form of a triangle, namely from [the church of] St. Richarius to [the

church of] St. Mary one covered walk from [the church of] St. Mary to the [church of] St. Benedict one covered walk,

and from St. Benedict to St. Richarius, likewise, one covered walk."

There are, however, other instances where claustrum stands for the whole of the claustral compound. A phrase in the

Gesta Aldrici (bishop of Le Mans, and written between 840 and 842) provides this example: "Claustrum iuxta ipsam

ecclesiam fecit, id est refectorium, dormitorium, cellarium"[50]

("and next to the church he built a cloister, i.e. the refectory

the dormitory, the cellar"); in the interesting passage in the Life of Eigil, Abbot of Fulda (written between 840 and 842)

we find this usage:

Vocantur ad consilium fratres. Quaesitum est, in quo loco aedificatio claustri congruentius potuisset aptari. Quidem dederunt

consilium, contra partem meridianam basilicae iuxta morem prioris; quidam autem, Romano more contra plagam occidentalem

satius poni, confirmant propter vicinitatem martyris qui in ea basilicae parte quiecit. Quorum concilio adsensum praebuere priores,

concordabant nihilominus et reliqua pars fratrum.[51]

"They called the brothers into council. The question was raised in which place the construction of the new cloister[52]

should be most suitably undertaken. Some advised that it should be placed against the southern part of the church like the

earlier cloister; others, however, claimed that it were more satisfactorily placed in the Roman manner against the western

side of the church, because of the nearness to the martyr who rests in this part of the church. As the priors agreed with

the advice of the latter, the remaining part of the brothers assented as well."

Even in the case of the title that defines the function of the Novitiate, on the Plan of St. Gall (hoc claustro oblati pulsantibus

adsociantur) the word may encompass the whole of the claustral complex, as the association of oblates and pulsantes, to

ranged around it.

In a few instances the word claustrum may also be used in a more limited sense as a substitute for porticus, "cloister

walk." Paul Meyvaert drew my attention to a passage in the Capitula Qualiter (written after 821 A.D.): "In claustris hora

lectionis summum silentium et summum studium lectionis ab omnibus haberi." Here claustri comes in the middle of a list of

buildings: "in oratorio", "in sacrario", "in hospitali", "in refectorio", "in dormitorio", and therefore must clearly stand

for "cloister walks."[53]

For the use of claustrum as pars pro toto for the entire monastery I refer to the sources quoted sub verbo by DuCange

and by Niermeyer.[54]

A typical example is in the Life of Duke William (d. 812), builder of the monastery of St. Guilhem-le-Desert

(Gellone) and protector of Benedict of Aniane:

Metitur etiam totius claustri spatium, domum refectionis atque dormitorium, domum etiam infirmorum et cellam novitiorum,

proaulam hospitum, Xenodochium pauperum, iunctum clibano pistrinum, de latere molendinum.[55]

"He measures, moreover, the space of the entire cloister, the refectory and the dormitory, the infirmary and the novitiate,

the house for distinguished guests, and the hospice for pilgrims and paupers, and the bakery next to the oven, as well

as the nearby mill."

In the fifteenth century, south of the Alps claustrum is used in secular parlance as a synonym for cortile, the galleried, often

double-storied range of porches opening peripherally inward onto the courts of Italian palaces. Wolfgang Lotz brought to

my attention two contracts in which the term appears with this connotation. One contract was made between Pope Paul II

and the three brothers Capranica, laying down the terms for the sale, in 1466, of a house valued at 500 ducats, and defining

this property as "unam domum . . . cum cameris, sala, coquina, reclaustro, porticali coperto columnato ante eam, . . . ."[56]

In the other contract, a donation deed of 1480 concerning the Palazzo Nardini, built for Stephano, Cardinal Nardini

between 1473 and 1478, it is specified that the gift applies to the palace "cum omnibus continentibus aedificiis et apotecis et

cum tribus claustris et porticibus et cum tribus introitibus a tribus viis, et cum omnis aulis, turribus."[57]

The term has thus come full circle: from "lock" or "bolt" to "bulwark", from military to spiritual enclosure, until

finally the image of the ubiquitous monastic cloister furnishes the word for a new concept in secular architecture for which,

because it was a novelty, there was no word to be borrowed from Classical Latin.

For the history of the term dormitorium, we refer to the discussion in the Glossary, below, s.v.

Benedicti regula, chap. 2, 23; ed. Hanslik, 1960, 23; ed. McCann,

1953, 21; ed. Steidle, 1952, 82.

Vita sancti Geretrudis, ed. Bruno Krusch, Mon.Germ.Hist., Script.

rer. Merovingicarum, II (Hanover, 1888), 348.

Supplex Libellus monachorum Fuldensium Carolo Imperatori porrectus

(812 et 817), chap. 5, ed. Semmler, Corp. Cons. Mon., I, Siegburg,

1963, 323.

For sources see Capitulare de villis, ed. Gareis, 1895, 51. Levillain's

translation of pisalis as séchoir (drying room) is misleading (Levillain,

1900, 342, note 2) as correctly pointed out by Lesne, VI, 1943, 364. The

Monks' Warming Room, truly enough, was an ideal place to dry the

monks' clothes after they had been washed in the adjacent Laundry, but

this was by no means its exclusive function (see I, 258).

On the meaning of porticus in Classical Latin, see Thesaurus, and

any standard dictionary, sub verbo.

In medieval Latin porticus is also used for spaces laterally attached

to a larger building, even if these spaces are not colonnaded, such as the

lateral spaces of the sixth-century church of St. Augustine's in Canterbury.

Cf. Baldwin Brown's "Note on the word PORTICUS" in

Brown, II, 1925, 89.

Richard Krautheimer (personal communication) believes that the

words pro porticia in the Charta Ecclesiae Cornutianae, issued in A.D. 471

(Duchesne, Liber Pontificalis, I, 1886, cxlvii, line 45) may be a reference

to "aisles", but stresses, at the same time, that the term is not used

anywhere else in this sense in the pre-Carolingian biographies of the

Popes. He warns against giving any weight to the Testamentum Domini as

containing evidence for the use of porticus in the sense of "aisle," since

the Latin translation of the Syrian text in which the term appears is

modern. This translation (Ephraem Rahmani Ignatius, Testamentum

Domini, Mainz, 1899) was not available to me. For previous discussion of

the subject see Suzanne Lewis, XXVIII, 1969, 95 and the literature

quoted there.

Chronica monasterii Casinensis, book III, chap. 26, ed. Lehmann-Brockhaus,

Schriftquellen, I, 1938, 476, No. 2277.

Vita s. Dunstani, ed. Stubbs, and Willelmo monacho Malmesbiriensi,

book I, §16, Rolls Series, LXIII, 1874, 271-72; ed. Lehmann-Brockhaus,

Lateinische Schriftquellen, I: 1, 1955, 494, No. 1834.

Lewis and Short, A Latin Dictionary, Oxford, 1945, 35: "that by

which anything is shut up or closed, a lock, bar, bolt."

Benedicti Regula, chap. 4, 78, ed. Rudolph Hanslik, Corpus

Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum LXXXV, Vienna, 1960, 35:

"Officina uero ubi haec omnia diligenter operemur, claustra sunt monasterii

et stauilitas in congregatione;" and ibid., chap. 67, 7 ed. Hanslik, 158:

"Siliter et qui praesumpserit claustra monasterii egredi."

Gregorii magni dialogi, I: 1, ed. Moricca, 1924, 14; confines: "in

quantum se intra cogitationes claustra custodivit," 2:3, ibid., p. 83.

Isidori Hispalensis episcopi Etymologiarum sive originum libri XX,

book XV, chap. 7, ed. W. M. Lindsay, II, Oxford, 1911 (no pagination):

"Fores et valvae claustra sunt, sed fores dicunt quae foras, valvae

quae intus revolvuntur, et duplices conplicabilesque sunt . . . . Claustra ab eo

quod claudantur dicta."

Vita Hrodberti episcopi Salzburgensis, chap. 8, ed. Levison, Mon.

Germ. Hist., Script. rerum Merovingicarum, VI, Hannover, 1887, 159.

Paul Meyvaert discussed the history of the term claustrum briefly in a

paper read at the symposium "Paradisus Claustralis—What is a Cloister?"

(New York, March 30-April 1, 1972), and more extensively in "The

Medieval Monastic Claustrum," Gesta XII (1973), 53-59.

Hildemar's dimensions coincide with those of the Monks' Cloister

on the Plan of St. Gall, where the yard plus its surrounding porches are

inscribed into an area 100 by 102 1/2 feet square and where it is easy to

check what would happen if one were to move the Dormitory (40 feet by

85 feet), Refectory (40 feet by 100 feet) and Cellar (40 feet by 87 1/2 feet)

from their peripheral positions into the interior of the cloister yard.

Hariulph, Chronique de l'Abbaye de Saint-Riquier, ed. Lot, 1894, 56;

ed. Schlosser, 1896, 259 No. 783.

Gesta Aldrici episcopi Cenomanensis, chap. 26, ed. Waitz, Mon.

Germ. Hist., Scriptores, XV, Hannover, 1887, 319.

Vita Eigilis Abbatis Fuldensis, chap, 19, ed. Waitz, Mon. Germ.

Hist., Scriptores, XV, Hannover, 1887, 231; and Schlosser, 1896, 112

No. 368.

The cloister referred to is the one which was started by Abbot

Eigil in 819 and completed during the abbacy of his successor Hrabanus

Maurus (822-840). See Vorromanische Kirchenbauten, I, 1966, 84.

Capitula Qualiter, ed. Frank, Corp. cons. mon., I, 1963, 355. For

other later occurrences of claustrum in the sense of "cloister walk" see

the passages quoted under this term in the index of vol. III/IV of the

Corpus consuetudinum monasticarum, under the subheadings locutio in

claustro, processionem per . . ., sedere in . . ., silentium in . . . .

VERSE

With regard to the meters found in the Plan, Charles W. Jones remarks: "The captions include four elegaic distychs[58]

and thirty-five hexameters.[59]

Although of scholastic regularity, they are not pedantically so. In the ninth century, as Leonine

rhymed hexameters were gaining favor, the uniform caesura in the third foot became increasingly standardized. But

among the thirty-five hexameters there are three hephthemimeral caesuras, and no Leonine verses.[60]

Indeed, there are

touches of liveliness. The concluding dactyls of the line on threshing (frugibus hic instat cunctis labor excutiendis)[61]

tend to

match the rhythm of the labor itself. And as Miss Patricia Clark points out, the most artful verses are the two set in the

semi-circular paradises of the church, which she diagrams as follows on the next page:

✫ alliteration of p and s

It is natural to try to explain the presence of verses in this utilitarian Plan as essentially mnemonic; but such an explanation

would be unsatisfactory. No supervising abbot or brother would find any of the common mnemonic aids in these

lines. They are, rather, the product of an artist who is taking joy in his work of art."

We have already drawn attention to the fact that the metric lines are primarily used to designate the general purpose of

a building. In order to make it clear that they define the whole and not part of the building, the author writes metric

verse inscription not into the interior of houses or buildings, but places them outside in a position of prominence (analogous

to chapter headings), parallel to and at a small distance from the entrance walls. There are, however, a few exceptions to

this rule. Some of the smaller guest and service buildings lack these general titles (House of the Physicians, House for

Bloodletting, Gardener's House, House of the Fowlkeepers). Conversely, in a few cases, metric titles are used internally

in places where the signal importance of the object or area they describe calls for special emphasis. All such instances,

except for one (Cross in the Cemetry) occur in the Church, where the inscriptions are associated with primary liturgical

stations (Altar of the Holy Cross, Altar of St. Peter, Altar of St. Paul) or appear in buildings directly connected with

the Church and vital for the regulation of the intercourse of the monastery with the outside world (the three porches of

the western atrium that control entry and exit of the monastic compound).

I can think of only one area in the whole aggregate of textual annotations where one would have wished for more explicit

information. Modern scholarship would have been spared the pains and pleasures of hundreds of pages of controversy,

had the widely spaced title in the longitudinal axis of the Church that reads "From East to West the length is 200 feet"

included in its wording a hint that this was a directive given to alter the original concept, in which the church was intended

to be 300 feet long.[62]

The decision to reduce the length of the Church from 300 feet to 200 feet—as the deposition

of the abbot of Fulda shows[63]

—cannot have been entirely free from emotional undertones. One senses a reflection of this

in a change of syntax, to which Bischoff has drawn attention: in contradistinction to all of the other legends of the Plan,

which are rendered as straight declarative statements, the majority of the titles stipulating that the Church should not be

built as large as was shown on the Plan, were put into imperative form (metire, moderare, sternito).[64]

On the entrance road, the cemetery cross, north and south of the

cross, and between the columns of the church.

The Petrus caption in the western apse of the Church and the

caption in the toolshed of the Gardener's House look as if they might be

hexameters, but they are not.

See Dag Norberg, "Introduction a l'étude de la versification latine

médiévale", Studia Latina Stockholmienses, 1958, 65.

VISUAL DISPLAY

In certain places the scribe makes use of a bold capitalis rustica rather than the delicate minuscule in which the majority

of the textual annotations are written. Here again he proceeds with discretion. Only buildings or areas that rank high in

the architectural ecology of the monastery are singled out for this distinction. Capitalized titles occur in ten places; five of

them in the context of the church: the widely spaced axial title that defines what its length should be; a hexameter that

defines the function of the presbytery; two hexameters in the western, and one in the eastern atrium. Outside of the church

capitalis rustica is found in the following places: In the bold meter that explains the function of the road of access to church

and the sick; in the word HORTUS inscribed into the outer paths of the Monks' Vegetable Garden (in widely spaced

letters); and in the two hexameters that explain the purpose of the two circular enclosures for the hens and the geese.

The choice of capitals for designating the Monks' Vegetable Garden and the enclosures for hens and geese is perhaps a

little surprising. In the two latter cases one might suspect that the scribe, faced with two magnificently free circular spaces

exuberantly let himself go. But in the case of the Monks' Vegetable Garden the use of capitals could not have been motivated

by the same reason, since the space available there is poorly suited to an inscription in capital letters. Might the

emphasis in both cases have something to do with the important place the produce of the garden and of the chicken yard

held in the monks' diet, and the fact that the flesh of chicken was the only meat of any living creature except fish permitted

on the monks' table?[65]

STYLE OF WRITING AND OTHER PALAEOGRAPHICAL DETAILS

It was to Bernhard Bischoff's credit that he established that the explanatory titles of the Plan were written in the

scriptorium of the monastery of Reichenau[66]

—a discovery of crucial importance for the evaluation of the historical context

in which the Plan was copied, and for the identification of the persons who were involved in this task.[67]

Bischoff distinguished

two hands: the hand of a young scribe ("main scribe") who wrote the majority of the explanatory titles (265

out of the total of 341, as well as the ten titles written in capital letters) and the hand of an older man who played the

role of supervisor or corrector (writer of the remaining 66 titles). Bischoff defines their respective share in the inscriptions

as follows:

MAIN SCRIBE

He is responsible for the letter of transmission, all of the titles written in capitalis rustica, and the majority of the other

titles. Most of these titles are written in dark brown ink.

The main scribe, Bischoff points out, writes in a crisp and delicate Carolingian minuscule of a kind that was common

among younger Carolingian scribes. His style of writing has a slightly insular touch and discloses clearly that he was not

trained in the Alamannic tradition of St. Gall and of the monastery of Reichenau. Certain peculiarities of his script suggest

that before joining the scriptorium of Reichenau, he spent some time in the abbey of Fulda. The particulars of his writing

Bischoff defines as follows: "He writes vertically and places his letters closely. The letters a and d appear in two variations,

on one hand in their closed Carolingian form (at the end of the word on occasion terminating with a sharp upstroke),

on the other hand open, with two points, more closely corresponding to the insular tradition, although the latter is usually

smaller. A long d alternates with a round d. In the g both arcs are closed; z rises above the letters of intermediate length,

and begins and ends with an almost horizontal stroke. Favorite ligatures are the letter combinations ct, en, er, et, rt; and

l, n, t when followed by an i. His favored abbreviations are: um (a simple r or the ligature -or with cross stroke; -us (dom');

also -ur (recitat') and insular symbols for est and id est.[68]

SECOND SCRIBE

From his hand are the plant designations in the Medicinal Herb Garden and in the Monks' Vegetable Garden, the tree

designations in the Orchard, and all of the inscriptions associated with the altars in the aisles of the church and in the

towers; furthermore, the additions infra and supra tabulatum in the House for Horses and Oxen, the supra camera et

solarium in the Abbot's House, as well as the words pausatio procuratoris (over erasure) in the lodging of the Master of the

Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers. Most of the titles of the second scribe are written in a light brown ink that did not retain

its original freshness as well as did the darker ink used by the main scribe. Of him, Bischoff says:

"The second scribe, likewise, `writes vertically,' but with relatively short ascenders and a certain trend toward loose but

regular distribution. In the alphabet he employs only the cc-a; the d is always straight. The shaft of the f begins with a

curved upstroke, occasionally even the shaft of the s; g is always open at the bottom. Favorite ligatures are ar (martini),

ect, em, ere, ex, and others; fra (a open), and re. These forms, especially the ligature fra as well as the delicate uniform

ductus of the script are closely related to that late fine style of Alamanic writing, of which the librarian Reginbert of

Reichenau (d. 846) availed himself certainly as one of its last masters"[69]

The dynamics of the interaction of these two scribes, who worked in close cooperation, as well as their relationship to

the high official for whom they performed their task, has been discussed in a previous chapter.[70]

For those among our

readers to whom palaeography is a new adventure, we are adding a few remarks about the abbreviations used in the textual

annotations of the Plan.

THE MOST COMMON ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE EXPLANATORY TITLES

The nasal bar is the sign commonly used for letters left out. The bar appears both in the middle of a word and at the end.

Almost always the omitted letters are readily supplied because the words are familiar. Examples: fr̄n̄ītas, ec̄l̄āe, nr̄ī, sc̄ī

sarcofagū, bibliothecā, dormitoriū, for fraternitas, ecclesiae, nostri, sancti, sarcophagus, bibliothecam, and dormitorium. In a few

instances, this sign is omitted through inadvertance. Examples: aucar̄ū, analogīū, sedendū, cū, mandat̄ū, earundē, seruantīū,

for aucarum, analogium, sedendum, cum, mandatum, earundem, seruantium.

A bar through the descender of the letter p stands for per and pre. Examples: semp, sup, pscrutinanda, pparanda, for semper,

super, perscrutinanda and preparanda.

A bar through the ascender of the letter b appears only once on the Plan, viz. in the dedicatory legend, in the name of

Abbot Gozbert: cozƀte for cozberte.

A period after the letter q indicates that the letters ue have been dropped. Examples: utcumq·, atq·, quoq·, for utcumque,

atque, and quoque.

A cross-stroked 1 stands for uel.

The ampersand stands for et. This sign is used both within and at the end of words as well as a symbol for the connecting

word "and". Examples: st&, exi&, cohaer&, col&ur, seru&ur, fa&us for stet, exiet, cohaeret, coletur, seruetur, and

faetus. This abbreviation survives in widespread use. A scattering of examples in current practice is included with the redrawn historic examples illustrated opposite.

Completion of ending orum and (in one case) arum. This sign always occurs after or or ar of this ending. Examples:

infirmorum, ferramentorum, porcariorum, pastorum, pigmentorum, eorum, tuarum for infirmorum, ferramentorum, porcariorum, pastorum,

pigmentorum, eorum, tuarum.

A period placed below a letter when it appears in conjunction with another letter placed above the line indicates that a

correction has been made. Examples: cabalḷͦrum, paupeṛͧm, buḅͧs for caballorum, pauperum, and bubus. Occasionally the

dot below the line is omitted. Examples: euangelacae, domum for euangeliacae and domus.

A period placed on either side of a letter deletes that letter. Example: ċlȯcleam in the Tower of St. Michael. In the House

of the Physicians on the other hand the first l of the misspelled word cubilulum is changed into a c by simply superimposing

the latter on the former.

A crescent-shaped apostrophe is used most frequently after a t, to supply the rest of the passive ending of a verb,

such as ur. Examples: conficiat͗ and triturant͗ for conficiatur and trituratur. It also appears, but more rarely, to show that

the letters us have been left off at the end of a word. Examples: camin͗ and dom͗ for caminus and domus.

Id est, "that is to say". Example: horreum·|·repositio fructuū annaliū for horreum id est repositio fructuum annalium.

This symbol is always est alone. Example: domus communis scolae id÷uacationis for domus communis scolae id est uacationis.

CAPRICIOUS ABBREVIATIONS

There are, lastly, not to be overlooked (as Charles W. Jones reminds me) what Lindsay, in his Notae Latinae, pp. 415ff,

calls "capricious abbreviations", e.g. dom for domus (Gardener's House —), necess for necessarium (Novitiate) and cub

for cubilia (House of Coopers and Wheelwrights —).

AMPERSANDS REDRAWN FROM VARIOUS SOURCES

524. VITA SANCTI BONIFATII. Karlsruhe

BADISCHE LANDESBIBLIOTHEK (Codex Augiensis CXXXVI, fol. 14v)

CAROLINE SCRIPT (9th century)

The full-page illustration reveals the main features of the great script created in the period

of Charlemagne, and further developed during the next two centuries. Unlike the great

formal court bookhands of the time, it is a cursive writing, a running hand conditioned by

economy and speed, with characteristics of both majuscule and minuscule. It is marked by

broad and sweeping lines widely spaced, letter forms clearly defined and articulated, smooth

flowing and finely proportioned to the page. Its slight slope (here, about 5° to 6°) was

perquisite to the urgent quest for speed because, by this device, slight deviations from angle

of tilt are scarcely detectible, as are deviations from the absolute verticality of formal

writing, courtly and elegant. Still, and this is one of its salient features, an air of elegance

dominates a page of finely executed Caroline script that betrays as myth the notion that a

degree of speed is inconsistent, when clarity is fused with a great portion of beauty.

Alcuin of York, in the years 781-790 at the court of Charlemagne, had been appointed

to the enterprise of creating, directing, and disseminating a vast program of education,

writing and learning throughout the empire. In 796 he was awarded the renowned abbey of

St. Martin at Tours. Here as abbot and director of probably the greatest school of its day,

Alcuin had ample time to pursue, till his death in 804, the minuscule and cursive style that

is known as Caroline script.

Later in Italy in the era of "New Learning" the Caroline script had decisive effect on

writing, type design, and printing that lasts to this day. The italic type before the reader's

eye is a direct derivative of that great writing. This legacy from Charlemagne is seen

throughout the world in all countries that employ the roman-based letter. Its place in the

history of civilization and learning is beyond appraisal.

E. B.

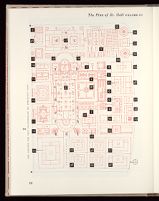

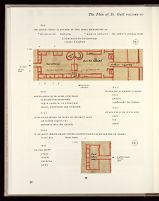

525. NOTE THE PLAN OF ST. GALL AS A SUBJECT

OF ILLUSTRATION IN VOLUMES I AND II

AND CATALOGUE OF INSCRIPTIONS FOLLOWING

VOLUMES I AND II

The Plan is shown in this work by two modes of illustration, tonal and line.

Tonal illustrations, shown as details of the Plan, in most cases are in color and

at the same size as the original, while line illustrations printed in black or in

red, often with overlays of the opposite color, occur in several different degrees

of reduction and represent the red line drawings of the original.

Reproduction of the Plan by line

The great Plan drawn on parchment survives in a remarkably good state as a

document. In centering attention, at original size, on its prime visual feature,

it will be observed that the red line drawing by which building and landscape

features are delineated is interrupted in many parts by short breaks, rarely

exceeding one or a few millimeters, where the ink has ceased to bond to the

parchment. These imperfections posed no problem in reproduction at reduced

dimensions. However, in certain parts the course of the red line drawing,

although clearly in evidence in original dimensions, is too meager to record

photographically a satisfactory printed image of the deteriorated condition of

the drawing at reduced dimensions. Resort to correction was performed as

follows.

By good fortune, the firm of E. Löpfe-Benz of Rohrschach, when printing

their important eight-color facsimile lithographic reproduction of the Plan of

St. Gall in 1952, also printed a small over-run edition of the red key-plate for

a few specialists, and their own use. This reproduction depicted the red line

drawing of the Plan at original size stripped of all other subject matter. With a

specimen of this key worksheet in our possession, which we obtained through

the kindness of the late Hans Bessler, by careful photography, several precision

prints were made on material of high dimensional stability and receptive to

pen and ink for retouching. On one print all defective parts of the line drawing

were corrected to yield a continuous line in all parts of the Plan, alterations

being restricted only to supplying in full strength those areas where the ink

had deteriorated or ceased to bond, but where unmistakable traces of its original

course were in clear evidence. When reduced to exactly one-fourth

original size, the print happily yielded an image satisfactory for reproduction

in printing. For greater reduction than one-fourth original size, prints as

described above required line widths to be retouched two times and in a few

cases, were retouched three times line width (1/10 × s, example, ill. I.xx).

Since the printed images at reduced size serve schematically or diagrammatically,

sometimes as red base color for a black overprinting, the often ugly

implications or connotation of "alteration" vanish. When the reader seeks a

degree of authenticity in the study of the delineation of the Plan drawing he

may turn to color reproductions shown original size in Volumes I and II, or

the following Catalogue.

Tonal Illustrations in Color

The tonal illustrations in color in this work are derived from the splendid

facsimile eight-color reproduction of the Plan of St. Gall printed in 1952,[71]

which portrays the great document in a high degree of fidelity to the original

that would be difficult to surpass. The procedure of derivation is accomplished

by means of the "optical color scanner," an instrument of photo-computer

antecedents, and available commercially only recently for application in the

printing arts. At the outset the hope of the authors had been to negotiate with

the eminent Swiss firm who printed the eight-color facsimile lithographic

edition in some scheme, one perhaps by which their color film or master negatives

could be made available. On learning these no longer existed and furthermore

knowing of the current ban on photographing the original parchment

because of the deleterious effect of strong lighting used in photographic procedure,

there was no alternative except to resort to the use of the scanner and

a copy of the facsimile reproduction.

A facsimile negative (probably on blue-sensitive film) in our possession, provided

us by Dr. Duft, was invaluable for reference but proved of little use as a

technical instrument since the stained areas of the parchment printed as great

black spaces lacking in detail. In color photography screening and dexterous

technical manipulation can correct for this condition, as is evidenced on

inspection of the facsimile Plan.

THE CATALOGUE OF INSCRIPTIONS

The remarks on certain problems of reproduction for printing in line when

drastic reduction in the dimensions of the image occurs, do not apply to the

color reproductions at the same size as the original. To some extent they apply

also to color reproduction at reduced scale but except for one instance (frontispiece,

fig. 1.X, I.xxviii) that was not a problem in this work. Enlargement

does offer grave problems, particularly when the original document to be copied

(called "the copy") has been "screened." The source from which the Plan

illustrations were scanned was screened copy. Thus, in the reproductions of the

following Catalogue, a high degree of printing technology, long experience,

great expertise, and close supervision with precise dot control are involved. By

tests and experimentation the use of one black plus two colors was found to

yield an image of visual quality adequate for the purpose of this work. The

greater degree of authenticity exemplified in high fidelity facsimile printing

with explicit veracity was not economically feasible nor even appropriate in a

work concerned with planning development and architecture more than with

great arts ancillary to it.

E.B.

As previously noted, it was produced under the auspices of the Historische

Verein des Kantons St. Gallen, on the initiative and under the supervision of

Dr. Johannes Duft and the late Hans Bessler.

In 1952, Firma E. Löpfe-Benz published a full-size facsimile in color

of the Plan of St. Gall from a series of eight negatives taken from the

Plan itself. This facsimile is visually the most coherent reproduction

of the Plan available to scholars, and stands in its own right as a

masterpiece of offset lithography. It is our understanding that copies of

this facsimile are still available from its publishers.

INDEX TO BUILDING NUMBERS OF THE PLAN

1. Church

a. Scriptorium below, Library above

b. Sacristy below, Vestry above

c. Lodging for Visiting Monks

d. Lodging of Master of the Outer School

e. Porter's Lodging

f. Porch giving access to House for Distinguished

Guests and to Outer Schoolg. Porch for reception of all visitors

h. Porch giving access to Hospice for Pilgrims and

Paupers and to servants' and herdsmen's

quartersi. Lodging of Master of the Hospice for Pilgrims and

Paupersj. Monks' Parlor

k. Tower of St. Michael

l. Tower of St. Gabriel

2. Annex for Preparation of Holy Bread and Holy Oil

3. Monks' Dormitory above, Warming Room below

4. Monks' Privy

5. Monks' Laundry and Bath House

6. Monks' Refectory below, Vestiary above

7. Monks' Cellar below, Larder above

8. Monks' Kitchen

9. Monks' Bake and Brew House

10. Kitchen, Bake, and Brew House for Distinguished

Guests

11. House for Distinguished Guests

12. Outer School

13. Abbot's House

14. Abbot's Kitchen, Cellar, and Bath House

15. House for Bloodletting

16. House of the Physicians

17. Novitiate and Infirmary

a. Chapel for the Novices

b. Chapel for the Sick

c. Cloister of the Novices

d. Cloister of the Sick

18. Kitchen and Bath for the Sick

19. Kitchen and Bath for the Novices

20. House of the Gardener

21. Goosehouse

22. House of the Fowlkeepers

23. Henhouse

24. Granary

25. Great Collective Workshop

26. Annex of the Great Collective Workshop

27. Mill

28. Mortar

29. Drying Kiln

30. House of Coopers and Wheelwrights, and Brewers'

Granary

31. Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers

32. Kitchen, Bake and Brew House for Pilgrims and

Paupers

33. House for Horses and Oxen and Their Keepers

34. House for the Vassals and Knights who travel in

the Emperor's Following

(identification not certain)

35. House for Sheep and Shepherds

36. House for Goats and Goatherds

37. House for Cows and Cowherds

38. House for Servants of Outlying Estates and for

Servants Travelling with the Emperor's Court

(not certain; cf. No. 34)

39. House for Swine and Swineherds

40. House for Brood Mares and Foals and Their

Keepers

W. Monks' Cloister Yard

X. Monks' Vegetable Garden

Y. Monks' Cemetery and Orchard

Z. Medicinal Herb Garden

NOTE: A trilingual index with each building identified in corresponding

French, German, and English may be seen in Volume I, page xxv.

THE DEDICATORY LEGEND OF THE PLAN[72]

WRITTEN IN THE UPPER MARGIN OF THE PLAN ABOVE THE MONKS' CEMETERY AND ORCHARD (ITEM Y, PLAN, PAGE 14)

Haec tibi dulcissime fili cozbte de posicione officinarum

paucis exemplata direxi · quibus sollertiam exerceas tuā

meamq · deuotionē utcumq · cognoscas · qua tuae bonae uolun

tati satisfacere me segnem non inueniri confido · Ne suspiceris

autem me haec ideo elaborasse · quod uos putemus nr̄īs indigere

magisteriis · sed potius ob amorē dei tibi soli pscrutinanda pinxisse

amicabili fr̄n̄itatis intuitu crede · Uale in xp̄ō semp̶ memor nri am̄·

For thee, my sweetest son Gozbertus, have I drawn out this briefly annotated copy

of the layout of the monastic buildings, with which you may exercise your ingenuity

and recognize my devotion, whereby I trust you do not find me slow

to satisfy your wishes. Do not imagine that I have undertaken this task

supposing you to stand in need of our instruction, but rather believe that

out of love of God and in the friendly zeal of brotherhood I have depicted this

for you alone to scrutinize. Farewell in Christ, always mindful of us, Amen.

‡ The Catalogue of Inscriptions is demonstrated in 166 separate color illustrations, each identified by a number, c.1, c.2, to c.166, pages 16 to 88.

ILLUSTRATIONS ARE SHOWN 1.5 TIMES ORIGINAL SIZE (EXCEPTION, c.135).

THE ENTRANCE ROAD TO THE CHURCH

ON THE LONGITUDINAL AXIS OF THE CHURCH EXTENDED TO THE WEST

This inscription is shown on the Plan, I, xx, and is discussed, I, 128.

NOTE For discussion of the use of CAPITALIS RUSTICA in writing certain inscriptions of the Plan, refer to the preface of this section, page 8, under Visual

Display. Other comments occur under Goosehouse, building 21, page 61, and Henhouse, building 23, page 63.

CAPITALIS RUSTICA occurs in the following parts of the Catalogue of Inscriptions:

| APPROACH TO THE CHURCH | ||

| 1. | The Entrance Road (shown above) | page 17 |

| WITHIN THE CONFINES OF THE CHURCH | ||

| In the West Atrium (building 1) | ||

| 2. | Within the covered arcade | pages 18, 19 |

| 3. | In the adjacent outdoor space, Paradisiacum | pages 18, 19 |

| 4. | Written on the longitudinal axis of the Church | pages 24, 25 |

| 5. | The Presbytery | page 29 |

| 6. | The East Atrium | page 30 |

| OUTSIDE THE CHURCH | ||

| 7. | The Novitiate (building 17) | page 54 |

| 8. | The Goosehouse (building 21) | page 61 |

| 9. | The Henhouse (building 23) | page 63 |

| 10. | The Monks' Vegetable Garden (Plot X) | page 83 |

1

THE CHURCH

THE WEST ATRIUM

✠ Blank area is treated under the subheading Western Apse, page 23.

For inscriptions and translations see opposite page

For facsimile color plan showing surrounding area, see I, 132.

IN THE COVERED WALK OF THE ATRIUM (OUTER SEMICIRCULAR SPACE)

IN THE OPEN AREA OF THE ATRIUM (INNER SEMICIRCULAR SPACE)

IN THE INTERSTICES BETWEEN THE PIERS SUPPORTING THE ROOF OF THE COVERED WALK

Has inter que pe des de nos mo de rare colum nas

Between these columns count ten feet

I: Three hexameters in concentric semicircles, appear in the bold CAPIYALIS RUSTICA (inner and outer lines) and in the crisp and delicate Carolingian

minuscule (middle line) that characterizes the hand of the main scribe who, before he came to the island monastery of Reichenau, must have spent some time

at the abbey of Fulda. His work on the Plan was supervised by an older scribe practising a late fine style of Alamanic writing very similar to that used by

the famous teacher, Reginbert of Reichenau.

For discussion, see text ATRIUM, I, 128

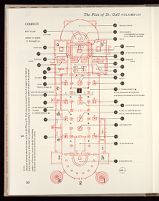

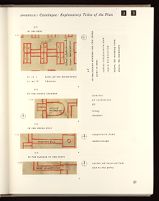

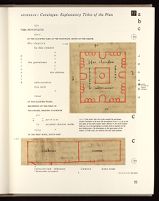

526. CHURCH

KEY PLAN

NOTE

Diagram showing where the items occur on the Plan of St. Gall that are treated in detail in pages 21 through 30.

Each item of the text is identified by a number corresponding to the locating key number shown in the diagram.

numbers 1 to 8 inclusive, (in nave), identify Column Range

for the north row and south row of church nave columns

NAVE

1

LECTERNS

2

PULPIT

3

ALTAR OF THE HOLY CROSS

NOTE Small black circles with numbers refer to locations shown on the Plan, page 20.

4

ALTAR OF ST. JOHN THE BAPTIST AND

ST. JOHN THE EVANGELIST

5

BAPTISMAL FONT

6

IN THE SECOND BAY (slightly east of column pair 1)

NOTE Small black circles with numbers refer to locations shown on the Plan, page 20.

*4-8: The ductus of all circles appearing on these pages shows clearly that they are not

instrument drawn; yet the two circles of the baptismal font (5) could hardly be so

regular had the hand of the draftsman not been guided by the compass-drawn

circles of the underlying original that the he traced.

IN WEST APSE

7

MEASUREMENTS

WRITTEN TRANSVERSELY ACROSS NAVE AND AISLES (BAY 7-8)

8

8: The measurements here listed are crucial for analysis of the scale of the Plan,

and conflict with dimensions given for the length of the Church (see further remarks,

page 24).

NOTE Small black circles with numbers refer to locations shown on the Plan, page 20.

9 (ON THE LONGITUDINAL AXIS OF THE CHURCH (SPACES BETWEEN LETTER GROUPS SHOWN CONTRACTED) ON THE LONGITUDINAL AXIS OF THE CHURCH (SPACES BETWEEN LETTER GROUPS CONTRACTED)

10 IN THE INTERSTICES BETWEEN THE SOUTHERN AND NORTHERN ROW OF COLUMNS IN THE INTERSTICES BETWEEN THE SOUTHERN AND NORTHERN ROW OF COLUMNS

11

The color plan, I, xxviii, will be found helpful to orient the reader with respect to these and other detail illustrations of the Catalogue.

10, 11: If the nave of the Church was 40 feet wide (as stated in its inscriptions, p. 23), its length according to the drawing should have been stated as being 300,

not 200 feet as requested in the axial title of the Church (9). By the same token the interstices of the nave columns should have been 20, not 12 feet as

postulated in its intercolumnar titles (10, 11).

The incompatibility of these figures and the rendering of the drawing itself has haunted a hundred years of scholarship. The conclusion that the Plan was

not drawn to scale was firmly held until Bockelmann suggested, and the present authors now state, that incompatibilities between drawing and titles expressed

a change in thought about the desired length of the Church that developed later than the completion of the drawing (for historical overview and detailed

discussion see I, 77-104).

NOTE Small black circles with numbers refer to locations shown on the Plan, page 20.

AISLES

12

NORTH AISLE

Titles for these two altars were written by the supervising scribe. All other altars of this

group were written by the main scribe.

13

SOUTH AISLE

14

NORTH AISLE

15

SOUTH AISLE

16

17

18

19

TRANSEPT

20

IN THE CROSSING SQUARE

NOTE Small black circles with numbers refer to locations shown on the Plan, page 20.

21

IN THE CROSSING SQUARE

22

23

24

25

*IN THE NORTH ARM OF THE TRANSEPT

26

NOTE Small black circles with numbers refer to locations shown on the Plan, page 20.

*

27

28

IN THE SOUTH ARM OF THE TRANSEPT

29

30

31

NOTE Small black circles with numbers refer to locations shown on the Plan, page 20.

For remarks on the Crypt, see

Figure 83 with caption, I, 130; Figure 123 with caption, I, 177.

THE PRESBYTERY

32

33

The altar occupies central position in the Presbytery.

For remarks on the Crypt, see

Figure 83 with caption, I, 130; Figure 123 with caption, I, 171.

THE EAST APSE

34

NOTE Small black circles with numbers refer to locations shown on the Plan, page 20.

CRYPT

35

THE EAST ATRIUM

36

NOTE Small black circles with numbers refer to locations shown on the Plan, page 20.

I a

SCRIPTORIUM BELOW, LIBRARY ABOVE

ON THE SOUTH AND NORTH OF THE TABLE

AT THE ENTRANCE TO THE LIBRARY FROM THE PRESBYTERY

I b

SACRISTY BELOW, VESTRY ABOVE

ON THE SOUTH AND NORTH OF THE TABLE

ON THE TABLES

I c

LODGING FOR VISITING MONKS

I d

SCHOOLMASTER'S LODGING

‡ Damage to the parchment, where noted above, invites conjecture in an attempt to

restore the break in the line of the drawing with a continuous wall line, or with a

doorway. The furniture arrangement and a door on the north wall suggest strongly the

former presence of a door in the Church wall, since this would permit the most direct

access to the Outer School for students who pass the Porter's station (see I.f, next

page). The alternate route, circuitous, seems unlikely—walking the full length of the

Church, across the north transept, through the quarters for visiting monks, then into

the school yard to the school.

I e

THE LODGING OF THE PORTER

IN THE EAST SPACE

IN THE WEST SPACE

I f

PORCH GIVING ACCESS TO HOUSE OF DISTINGUISHED GUESTS & TO OUTER SCHOOL

If: The first half of this hexameter was written by the supervising scribe, the

second half by the main scribe. On their interaction see I, 13-14.

I g

PORCH FOR RECEPTION OF ALL VISITORS TO THE MONASTERY

Ig: The word HABEBIT was partially covered by the overlapping margin of sheet

5 when the latter was attached to sheet 1. The inscriptions on the latter,

therefore, must have been completed before the two were joined (cf. I, 35-50).

I h

PORCH GIVING ACCESS TO THE QUARTERS OF THE SERFS AND TO THE HOSPICE

I i

LODGING OF THE MASTER OF THE HOSPICE FOR PILGRIMS AND PAUPERS

I j

THE MONKS' PARLOR

I k

THE TOWER OF ST. MICHAEL

Ik: The inscriptions in the two towers are from the hand of the supervising scribe and

very characteristic of his style. Strangely enough the titles in the outer ring of the spiral

are rendered in the dark brown ink of the main scribe, and were probably entered before

the altar designations in the innermost rings. These are written in the pale brown ink of

all other entries of the supervising scribe (and like them are difficult to decipher).

I l

THE TOWER OF ST. GABRIEL

2

THE ANNEX FOR PREPARATION OF HOLY BREAD AND OIL

For facsimile color plan see I. 260.

3

THE DORMITORY AND WARMING ROOM

3.1

THE ADJACENT CLOISTER WALK

For facsimile color plans see pp. I, 257, 260.

See site plan and caption, p. 81.

*

3.2

IN THE BEDS

3.3

IN THE FIRING CHAMBER

3.4

IN THE SMOKE DUCT

3.5

IN THE PASSAGE TO THE PRIVY

3.6

IN THE PASSAGE FROM WARMING ROOM TO MONKS' LAUNDRY AND BATH HOUSE

4

THE MONKS' PRIVY

4: The presence of a light (lucerna) in the privy is stipulated as a necessity,

in a 9th-century commentary to the Rule of St. Benedict (see I, 259).

5

THE MONKS' LAUNDRY AND

BATH HOUSE

5: Whether or not, or how often, monks should be allowed to bathe was a

highly controversial issue in monastic life. As in all similar matters, St.

Benedict took a tolerant stand (see I, 262-67).

6

THE MONKS' REFECTORY AND VESTIARY ABOVE IT

6.1

IN THE CLOISTER WALK ADJACENT TO THE REFECTORY (SEE SITE PLAN PAGE 81)

6.2

THE CENTRAL PART OF THE REFECTORY

For facsimile plan see I, 263.

6.2.1

READERS LECTERN

6.2.2

IN FRONT OF THE LECTERN

6.2.3

ON THE VISITORS' TABLE

*6.2: The design of the Refectory entrance is unique on the

Plan. It strikingly resembles a modern revolving door, but

was probably a draft-blocking construction divided internally

into two parallel passages for entering and leaving.

6.3

IN THE EASTERN HALF OF THE HALL

6.3.1

ON THE BENCH ON THE SOUTH HALL

6.3.2

IN THE FRONT OF THE BENCH

6.3.3

ADJACENT TO (SOUTH) OF THE ABBOT'S BENCH

6.3.4

THE GREAT U-SHAPED TABLE ON MAIN AXIS OF THE REFECTORY

6.3.5

ON THE BENCH NORTH OF THE ABBOT'S TABLE

6.4

IN THE WESTERN HALF OF THE HALL

6.4.1

JUST WEST OF THE VISITORS' TABLE

6.4.2

ON THE CUPBOARD NEAR THE EXIT

AND ADJACENT TO THE KITCHEN

7

THE MONKS' CELLAR AND LARDER

7.1

THE WESTERN WALK OF THE CLOISTERS (SEE SITE PLAN PAGE 81)

7.2

ON THE AXIS OF THE BUILDING FROM SOUTH TO NORTH

For facsimile color plan see I, 258.

7.2.1

ON THE WEST SIDE (TOP ROW)

7.2.2

ON THE EAST SIDE (BOTTOM ROW)

7.2: On the daily allowance of wine in St. Benedicts's time and at the

time the Plan was drawn, see I, 296-303. On the question of the scale

of the barrels and their sufficiency, see I, 303-305. see also I, 286

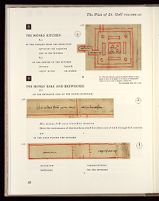

8

THE MONKS' KITCHEN

8.1

IN THE PASSAGE FROM THE REFECTORY

8.2

IN THE CENTER OF THE KITCHEN

8.2: The term FORNAX is used in the Monks' Kitchen to mean

hearth or stove. In the Bakery of the House for Distinguished

Guests (10:3) it is used to designate a baking oven.

For facsimile plan see I, 263.

9

THE MONKS' BAKE AND BREWHOUSE

9.1

ON THE ENTRANCE SIDE OF THE HOUSE (EXTERIOR)

*9.2

IN THE AISLE FACING THE KITCHEN

*

9.3

IN THE BREWERY

9.2.1

ON THE NORTH SIDE

9.3.2

IN THE SOUTH AISLE

9.4

IN THE BAKERY

9.4.1

9.4.2

IN THE SOUTH AISLE

*For an outline plan, size of original, 1:192, see II, 138.

9.4.3

IN THE EAST AISLE OF THE BAKE & BREW HOUSE

9.4: The drawing fails to show access from the bakery to the lean-to where flour is

stored, or to the aisle which contains the kneading trough. This is among the few

genuine oversights of the drafter of the Plan. See I, 61-66 on rendering of doors, and I,

65-73 on oversights.

10

KITCHEN, BAKE, AND BREW HOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS

10.1

IN THE KITCHEN

10.2

IN THE LARDER

10.3

IN THE MAIN ROOM OF THE BAKERY

10.4

IN THE MAIN ROOM OF THE BREWERY

10.5

IN THE SOUTH AISLE OF THE BAKERY

10.6

IN THE SOUTH AISLE OF THE BREWERY

For facsimile color plan see II, 144.

For author's interpretation see II, 154.

The original form of this not easily readable word, as written by the

main scribe, appears to have been intriuendae, a gerundive form mistakenly

formed from the perfect stem (intrivi) of the verb interere instead

of from its present stem (intero). The supervising scribe discovered and

corrected this faulty conjunction by striking out the letters riu and

replacing them above the line by the letters er. I am indebted to my

colleague Charles E. Murgia both for the palaeographical and grammatical

interpretation of this title. The verb interere, literally `to bruise'

or `to crumble' is commonly used in Classical Latin to designate the

process of transforming small broken-up substances (such as grain

ground into flour) into a pap or paste by mixing them with water or

some other liquid. See Lewis and Short, Classical Dictionary and

Thesaurus Linguae Latinae, s.v.—W.H.

11

THE HOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS

11.1

ALONG THE ENTRANCE SIDE

This building, too, serves for the reception of guests

11.2

IN THE SOUTHERN AISLE

11.2.1

EASTERLY AREA

11.2.2

IN THE CENTRAL AREA

11.2.3

WESTERLY AREA

11.3

IN THE PRINCIPAL HALL

* *For facsimile color plan see II, 144.

For authors' interpretation see II, 146.

11.3

IN THE PRINCIPAL HALL

11.3.1

IN THE EAST SIDE (ON EACH SIDE OF A DOORWAY)

11.3.2

IN THE CENTER SQUARE

11.3.2: Among the guest and service structures of the Plan, this is the

only one in which the large square at the center of the house is termed

LOCUS FOCI. In two other houses the similar square is termed TESTO (see

above, 12.2, 1, 2, and below, 31.4.1). The two terms are crucial for

identification of the building type (see II, 117-18).

11.3.3

NORTH OF THE FIRE PLACE

11.3.4

ON THE TABLE

*11.4

IN THE NORTH AISLE

11.4.1

IN THE EAST AND IN THE WEST SPACES

11.4.2

TO THE NORTH OF EACH OF THESE SPACES

*

11.5

IN THE CHAMBERS FOR THE GUESTS UNDER THE LEAN-TO'S

11.5.1

IN THE EAST SIDE OF THE PRINCIPAL HALL

For the multivalence of the term CAMINATA, here meaning heatable room,

elsewhere meaning corner fireplace (Abbot's House, 13-4, below, p. 50) see II,

123ff.

11.5.2

IN THE WEST SIDE OF THE PRINCIPAL HALL

11.6

IN THE PRIVY

*

12

THE OUTER SCHOOL

12.1 ALONG THE ENTRANCE SIDE

For facsimile color plan see II, 169.

For author's interpretation see II, I, 170.

*12.3

IN THE OUTER ROOMS READ CLOCKWISE BEGINNING ON THE SOUTH ROWS

12.2 IN THE MAIN HALL

12.2.1 SQUARE, LEFT CENTER

12.2.2 SQUARE, RIGHT CENTER

*

12.4

IN THE PASSAGE TO THE PRIVY

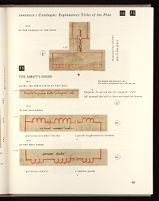

13

THE ABBOT'S HOUSE

13.1

ALONG THE FENCE SOUTH OF THIS HALL

For facsimile color plan see I, 130.

For authors' interpretation see I, 318, 320, 322.

13.2

IN THE EAST PORCH

13.3

IN THE WEST PORCH

*

13.4

THE HOUSE ITSELF IS DIVIDED IN TWO AREAS DESIGNATED AS

13.4.1

WRITTEN ACROSS THE TWO ROOMS IS THE PHRASE

(in the hand of the second scribe)

13.4.2

IN THE PASSAGE BETWEEN THE CHURCH AND THE ABBOT'S HOUSE

13.4.3

IN THE ABBOT'S BEDROOM READING COUNTER CLOCKWISE STARTING ON THE EAST NEAR THE CHIMNEY

** The words DORMITORIUM and MANSIO ABBATIS, designating the

Abbot's dormitory and living room, are in the hand of the main scribe.

The titles SUPER CAMERA, ET SOLARIUM, were added by the supervising

scribe. The word DORMITORIUM, located in the center of the space it

defines, suggests that the main scribe did not yet realize the necessity

for a second title below it. He must have become aware of that need

before he wrote the title MANSIO ABBATIS. Its position in the eastern

half of the room suggests that a second title was to follow in a corresponding

position in its western half. (A similar condition exists in the

House for Horses and Oxen, 33.2, 33.7).

‡ The term CAMINATA written into the ovoid symbols in the contiguous

corners of these two rooms is crucial for their interpretation as corner

fireplaces. There are many of them on the Plan, but only in facilities for

high ranking monastic officials or guests (see I.c, d, e, i, w, 11, 13, 17.c,

d, 20). For the use of CAMINATA as "heatable room" see comments

to the House for Distinguished Guests, 11.

13.4.4

ON EACH SIDE OF ENTRANCE TO CHURCH

13.4.5

ON EACH SIDE OF THE SITTING ROOM

13.5

IN THE PRIVY

14