| Sam Lawson's Oldtown fireside stories | ||

THE GHOST IN THE MILL.

COME, Sam, tell us a

story,” said I, as Harry

and I crept to his

knees, in the glow

of the bright evening

firelight; while Aunt

Lois was busily rattling

the tea-things,

and grandmamma, at

the other end of the fireplace, was quietly setting the

heel of a blue-mixed yarn stocking.

In those days we had no magazines and daily papers,

each reeling off a serial story. Once a week,

its slender stock of news and editorial; but all the

multiform devices — pictorial, narrative, and poetical

— which keep the mind of the present generation

ablaze with excitement, had not then even an existence.

There was no theatre, no opera; there were

in Oldtown no parties or balls, except, perhaps, the

annual election, or Thanksgiving festival; and when

winter came, and the sun went down at half-past

four o'clock, and left the long, dark hours of evening

to be provided for, the necessity of amusement became

urgent. Hence, in those days, chimney-corner

story-telling became an art and an accomplishment.

Society then was full of traditions and narratives

which had all the uncertain glow and shifting mystery

of the firelit hearth upon them. They were

told to sympathetic audiences, by the rising and falling

light of the solemn embers, with the hearthcrickets

filling up every pause. Then the aged told

their stories to the young, — tales of early life; tales

of war and adventure, of forest-days, of Indian captivities

and escapes, of bears and wild-cats and panthers,

of rattlesnakes, of witches and wizards, and

“Do, do, tell us a story.”—Page 3.

[Description: 703EAF. Illustration page. Image of two young boys sitting on stools at the feet of a middle aged man. There is an older couple sitting close to the fire in the background.]

providences.

In those days of early Massachusetts, faith and

credence were in the very air. Two-thirds of New

England was then dark, unbroken forests, through

whose tangled paths the mysterious winter wind

groaned and shrieked and howled with weird noises

and unaccountable clamors. Along the iron-bound

shore, the stormful Atlantic raved and thundered,

and dashed its moaning waters, as if to deaden

and deafen any voice that might tell of the settled

life of the old civilized world, and shut us forever

into the wilderness. A good story-teller, in those

days, was always sure of a warm seat at the hearthstone,

and the delighted homage of children; and

in all Oldtown there was no better story-teller than

Sam Lawson.

“Do, do, tell us a story,” said Harry, pressing

upon him, and opening very wide blue eyes, in which

undoubting faith shone as in a mirror; “and let it

be something strange, and different from common.”

“Wal, I know lots o' strange things,” said Sam,

looking mysteriously into the fire. “Why, I know

they wa'n't so; but then they is so for all that.”

“Oh, do, do, tell us!”

“Why, I should scare ye to death, mebbe,” said

Sam doubtingly.

“Oh, pooh! no, you wouldn't,” we both burst out

at once.

But Sam was possessed by a reticent spirit, and

loved dearly to be wooed and importuned; and so

he only took up the great kitchen-tongs, and smote

on the hickory forestick, when it flew apart in the

middle, and scattered a shower of clear bright coals

all over the hearth.

“Mercy on us, Sam Lawson!” said Aunt Lois in

an indignant voice, spinning round from her dishwashing.

“Don't you worry a grain, Miss Lois,” said Sam

composedly. “I see that are stick was e'en a'most

in two, and I thought I'd jest settle it. I'll sweep

up the coals now,” he added, vigorously applying

a turkey-wing to the purpose, as he knelt on the

hearth, his spare, lean figure glowing in the blaze

of the firelight, and getting quite flushed with exertion.

“There, now!” he said, when he had brushed over

and under and between the fire-irons, and pursued

the retreating ashes so far into the red, fiery citadel,

that his finger-ends were burning and tingling, “that

are's done now as well as Hepsy herself could 'a'

done it. I allers sweeps up the haarth: I think it's

part o' the man's bisness when he makes the fire.

But Hepsy's so used to seein' me a-doin' on't, that

she don't see no kind o' merit in't. It's just as

Parson Lothrop said in his sermon, — folks allers

overlook their common marcies” —

“But come, Sam, that story,” said Harry and I

coaxingly, pressing upon him, and pulling him down

into his seat in the corner.

“Lordy massy, these 'ere young uns!” said Sam.

“There's never no contentin' on 'em: ye tell 'em

one story, and they jest swallows it as a dog does

a gob o' meat; and they're all ready for another.

What do ye want to hear now?”

Now, the fact was, that Sam's stories had been told

us so often, that they were all arranged and ticketed

in our minds. We knew every word in them, and

could set him right if he varied a hair from the

Still we shivered, and clung to his knee, at

the mysterious parts, and felt gentle, cold chills run

down our spines at appropriate places. We were

always in the most receptive and sympathetic condition.

To-night, in particular, was one of those

thundering stormy ones, when the winds appeared

to be holding a perfect mad carnival over my grandfather's

house. They yelled and squealed round the

corners; they collected in troops, and came tumbling

and roaring down chimney; they shook and

rattled the buttery-door and the sinkroom-door

and the cellar-door and the chamber-door, with a

constant undertone of squeak and clatter, as if at

every door were a cold, discontented spirit, tired of

the chill outside, and longing for the warmth and

comfort within.

“Wal, boys,” said Sam confidentially, “what'll

ye have?”

“Tell us `Come down, come down!'” we both

shouted with one voice. This was, in our mind, an

“A No. 1” among Sam's stories.

“Ye mus'n't be frightened now,” said Sam paternally.

“Oh, no! we ar'n't frightened ever,” said we both

in one breath.

“Not when ye go down the cellar arter cider?”

said Sam with severe scrutiny. “Ef ye should be

down cellar, and the candle should go out, now?”

“I ain't,” said I: “I ain't afraid of any thing. I

never knew what it was to be afraid in my life.”

“Wal, then,” said Sam, “I'll tell ye. This 'ere's

what Cap'n Eb Sawin told me when I was a boy

about your bigness, I reckon.

“Cap'n Eb Sawin was a most respectable man.

Your gran'ther knew him very well; and he was a

deacon in the church in Dedham afore he died. He

was at Lexington when the fust gun was fired agin

the British. He was a dreffle smart man, Cap'n Eb

was, and driv team a good many years atween here

and Boston. He married Lois Peabody, that was

cousin to your gran'ther then. Lois was a rael

sensible woman; and I've heard her tell the story

as he told her, and it was jest as he told it to me, —

jest exactly; and I shall never forget it if I live to

be nine hundred years old, like Mathuselah.

“Ye see, along back in them times, there used to

fall, a-peddlin' goods, with his pack on his back; and

his name was Jehiel Lommedieu. Nobody rightly

knew where he come from. He wasn't much of a

talker; but the women rather liked him, and kind

o' liked to have him round. Women will like some

fellows, when men can't see no sort o' reason why

they should; and they liked this 'ere Lommedieu,

though he was kind o' mournful and thin and shad-bellied,

and hadn't nothin' to say for himself. But

it got to be so, that the women would count and

calculate so many weeks afore 'twas time for Lommedieu

to be along; and they'd make up gingersnaps

and preserves and pies, and make him stay

to tea at the houses, and feed him up on the best

there was: and the story went round, that he was

a-courtin' Phebe Ann Parker, or Phebe Ann was

a-courtin' him, — folks didn't rightly know which.

Wal, all of a sudden, Lommedieu stopped comin'

round; and nobody knew why, — only jest he didn't

come. It turned out that Phebe Ann Parker had

got a letter from him, sayin' he'd be along afore

Thanksgiving; but he didn't come, neither afore

and finally the women they gin up lookin' for him.

Some said he was dead; some said he was gone to

Canada; and some said he hed gone over to the Old

Country.

“Wal, as to Phebe Ann, she acted like a gal o'

sense, and married 'Bijah Moss, and thought no more

'bout it. She took the right view on't, and said she

was sartin that all things was ordered out for the

best; and it was jest as well folks couldn't always

have their own way. And so, in time, Lommedieu

was gone out o' folks's minds, much as a last year's

apple-blossom.

“It's relly affectin' to think how little these 'ere

folks is missed that's so much sot by. There ain't

nobody, ef they's ever so important, but what the

world gets to goin' on without 'em, pretty much as

it did with 'em, though there's some little flurry

at fust. Wal, the last thing that was in anybody's

mind was, that they ever should hear from Lommedieu

agin. But there ain't nothin' but what has

its time o' turnin' up; and it seems his turn was to

come.

“Wal, ye see, 'twas the 19th o' March, when

Cap'n Eb Sawin started with a team for Boston.

That day, there come on about the biggest

snow-storm that there'd been in them parts sence

the oldest man could remember. 'Twas this 'ere fine,

siftin' snow, that drives in your face like needles,

with a wind to cut your nose off: it made teamin'

pretty tedious work. Cap'n Eb was about the toughest

man in them parts. He'd spent days in the

woods a-loggin', and he'd been up to the deestrict

o' Maine a-lumberin', and was about up to any sort o'

thing a man gen'ally could be up to; but these 'ere

March winds sometimes does set on a fellow so, that

neither natur' nor grace can stan' 'em. The cap'n

used to say he could stan' any wind that blew one

way 't time for five minutes; but come to winds that

blew all four p'ints at the same minit, — why, they

flustered him.

“Wal, that was the sort o' weather it was all day:

and by sundown Cap'n Eb he got clean bewildered,

so that he lost his road; and, when night came on,

he didn't know nothin' where he was. Ye see the

country was all under drift, and the air so thick with

fact was, he got off the Boston road without knowin'

it, and came out at a pair o' bars nigh upon Sherburn,

where old Cack Sparrock's mill is.

“Your gran'ther used to know old Cack, boys.

He was a drefful drinkin' old crittur, that lived there

all alone in the woods by himself a-tendin' saw and

grist mill. He wa'n't allers jest what he was then.

Time was that Cack was a pretty consid'ably likely

young man, and his wife was a very respectable

woman, — Deacon Amos Petengall's dater from

Sherburn.

“But ye see, the year arter his wife died, Cack he

gin up goin' to meetin' Sundays, and, all the tithing-men

and selectmen could do, they couldn't get him

out to meetin'; and, when a man neglects means o'

grace and sanctuary privileges, there ain't no sayin'

what he'll do next. Why, boys, jist think on't! —

an immortal crittur lyin' round loose all day Sunday,

and not puttin' on so much as a clean shirt, when

all 'spectable folks has on their best close, and is to

meetin' worshippin' the Lord! What can you spect

to come' of it, when he lies idlin' round in his old

Devil should be arter him at last, as he was arter

old Cack?”

Here Sam winked impressively to my grandfather

in the opposite corner, to call his attention to the

moral which he was interweaving with his narrative.

“Wal, ye see, Cap'n Eb he told me, that when he

come to them bars and looked up, and saw the dark

a-comin' down, and the storm a-thickenin' up, he felt

that things was gettin' pretty consid'able serious.

There was a dark piece o' woods on ahead of him inside

the bars; and he knew, come to get in there, the

light would give out clean. So he jest thought he'd

take the hoss out o' the team, and go ahead a little,

and see where he was. So he driv his oxen up ag'in

the fence, and took out the hoss, and got on him, and

pushed along through the woods, not rightly knowin'

where he was goin'.

“Wal, afore long he see a light through the trees;

and, sure enough, he come out to Cack Sparrock's old

mill.

“It was a pretty consid'able gloomy sort of a place,

that are old mill was. There was a great fall of water

deep pool; and it sounded sort o' wild and lonesome:

but Cap'n Eb he knocked on the door with his whip-handle,

and got in.

“There, to be sure, sot old Cack beside a great

blazin' fire, with his rum-jug at his elbow. He was a

drefful fellow to drink, Cack was! For all that, there

was some good in him, for he was pleasant-spoken and

'bliging; and he made the cap'n welcome.

“`Ye see, Cack,' said Cap'n Eb, `I 'm off my road,

and got snowed up down by your bars,' says he.

“`Want ter know!' says Cack. `Calculate you'll

jest have to camp down here till mornin',' says he.

“Wal, so old Cack he got out his tin lantern, and

went with Cap'n Eb back to the bars to help him

fetch along his critturs. He told him he could put 'em

under the mill-shed. So they got the critturs up to

the shed, and got the cart under; and by that time

the storm was awful.

“But Cack he made a great roarin' fire, 'cause, ye

see, Cack allers had slab-wood a plenty from his mill;

and a roarin' fire is jest so much company. It sort o'

keeps a fellow's spirits up, a good fire does. So Cack

o' toddy; and he and Cap'n Eb were havin' a tol'able

comfortable time there. Cack was a pretty good

hand to tell stories; and Cap'n Eb warn't no way backward

in that line, and kep' up his end pretty well:

and pretty soon they was a-roarin' and haw-hawin'

inside about as loud as the storm outside; when all of

a sudden, 'bout midnight, there come a loud rap on

the door.

“`Lordy massy! what's that?' says Cack. Folks

is rather startled allers to be checked up sudden when

they are a-carryin' on and laughin'; and it was such

an awful blowy night, it was a little scary to have a

rap on the door.

“Wal, they waited a minit, and didn't hear nothin'

but the wind a-screechin' round the chimbley; and

old Cack was jest goin' on with his story, when the

rap come ag'in, harder'n ever, as if it'd shook the

door open.

“`Wal,' says old Cack, `if 'tis the Devil, we'd

jest as good's open, and have it out with him to onst,'

says he; and so he got up and opened the door, and,

sure enough, there was old Ketury there. Expect

She used to come to meetin's sometimes, and her husband

was one o' the prayin' Indians; but Ketury was

one of the rael wild sort, and you couldn't no more

convert her than you could convert a wild-cat or a

painter [panther]. Lordy massy! Ketury used to

come to meetin', and sit there on them Indian benches;

and when the second bell was a-tollin', and when Parson

Lothrop and his wife was comin' up the broad

aisle, and everybody in the house ris' up and stood,

Ketury would sit there, and look at 'em out o' the corner

o' her eyes; and folks used to say she rattled them

necklaces o' rattlesnakes' tails and wild-cat teeth, and

sich like heathen trumpery, and looked for all the

world as if the spirit of the old Sarpent himself was

in her. I've seen her sit and look at Lady Lothrop

out o' the corner o' her eyes; and her old brown baggy

neck would kind o' twist and work; and her eyes they

looked so, that 'twas enough to scare a body. For

all the world, she looked jest as if she was a-workin'

up to spring at her. Lady Lothrop was jest as kind

to Ketury as she always was to every poor crittur.

She'd bow and smile as gracious to her when meetin'

meetin'; but Ketury never took no notice. Ye see,

Ketury's father was one o' them great powwows down

to Martha's Vineyard; and people used to say she was

set apart, when she was a child, to the sarvice o' the

Devil: any way, she never could be made nothin' of

in a Christian way. She come down to Parson

Lothrop's study once or twice to be catechised; but

he couldn't get a word out o' her, and she kind o'

seemed to sit scornful while he was a-talkin'. Folks

said, if it was in old times, Ketury wouldn't have been

allowed to go on so; but Parson Lothrop's so sort

o' mild, he let her take pretty much her own way.

Everybody thought that Ketury was a witch: at least,

she knew consid'able more'n she ought to know, and

so they was kind o' 'fraid on her. Cap'n Eb says he

never see a fellow seem scareder than Cack did when

he see Ketury a-standin' there.

“Why, ye see, boys, she was as withered and wrinkled

and brown as an old frosted punkin-vine; and her

little snaky eyes sparkled and snapped, and it made

yer head kind o' dizzy to look at 'em; and folks used

to say that anybody that Ketury got mad at was

matter what day or hour Ketury had a mind to rap at

anybody's door, folks gen'lly thought it was best to

let her in; but then, they never thought her coming

was for any good, for she was just like the wind, — she

came when the fit was on her, she staid jest so long

as it pleased her, and went when she got ready, and

not before. Ketury understood English, and could

talk it well enough, but always seemed to scorn it,

and was allers mowin' and mutterin' to herself in Indian,

and winkin' and blinkin' as if she saw more

folks round than you did, so that she wa'n't no way

pleasant company; and yet everybody took good care

to be polite to her.

So old Cack asked her to come in, and didn't make

no question where she come from, or what she come

on; but he knew it was twelve good miles from where

she lived to his hut, and the snow was drifted above

her middle: and Cap'n Eb declared that there wa'n't

no track, nor sign o' a track, of anybody's coming

through that snow next morning.”

“How did she get there, then?” said I.

“Didn't ye never see brown leaves a-ridin' on the

wind,' and I'm sure it was strong enough to fetch her.

But Cack he got her down into the warm corner,

and he poured her out a mug o' hot toddy, and give

her: but ye see her bein' there sort o' stopped the

conversation; for she sot there a-rockin' back'ards and

for'ards, a-sippin her toddy, and a-mutterin', and

lookin' up chimbley.

“Cap'n Eb says in all his born days he never hearn

such screeches and yells as the wind give over that

chimbley; and old Cack got so frightened, you could

fairly hear his teeth chatter.

“But Cap'n Eb he was a putty brave man, and he

wa'n't goin' to have conversation stopped by no woman,

witch or no witch; and so, when he see her mutterin',

and lookin' up chimbley, he spoke up, and says

he, `Well, Ketury, what do you see?' says he.

`Come, out with it; don't keep it to yourself.' Ye see

Cap'n Eb was a hearty fellow, and then he was a

leetle warmed up with the toddy.

“Then he said he see an evil kind o' smile on Ketury's

face, and she rattled her necklace o' bones and

snakes' tails; and her eyes seemed to snap; and she

come down! let 's see who ye be.'

“Then there was a scratchin' and a rumblin' and

a groan; and a pair of feet come down the chimbley,

and stood right in the middle of the haarth, the toes

pi'ntin' out'rds, with shoes and silver buckles a-shinin'

in the firelight. Cap'n Eb says he never come

so near bein' scared in his life; and, as to old Cack,

he jest wilted right down in his chair.

“Then old Ketury got up, and reached her stick up

chimbley, and called out louder, `Come down, come

down! let's see who ye be.' And, sure enough, down

came a pair o' legs, and j'ined right on to the feet:

good fair legs they was, with ribbed stockings and

leather breeches.

“`Wal, we're in for it now,' says Cap'n Eb. `Go

it, Ketury, and let's have the rest on him.'

“Ketury didn't seem to mind him: she stood there

as stiff as a stake, and kep' callin' out, `Come down,

come down! let's see who ye be.' And then come

down the body of a man with a brown coat and yellow

vest, and j'ined right on to the legs; but there wa'n't

no arms to it. Then Ketury shook her stick up chimbley,

came down a pair o' arms, and went on each side o'

the body; and there stood a man all finished, only

there wa'n't no head on him.

“`Wal, Ketury,' says Cap'n Eb, `this 'ere's getting

serious. I 'spec' you must finish him up, and let's

see what he wants of us.'

“Then Ketury called out once more, louder'n ever,

`Come down, come down! let's see who ye be.' And,

sure enough, down comes a man's head, and settled

on the shoulders straight enough; and Cap'n Eb, the

minit he sot eyes on him, knew he was Jehiel Lommedieu.

“Old Cack knew him too; and he fell flat on his face,

and prayed the Lord to have mercy on his soul: but

Cap'n Eb he was for gettin' to the bottom of matters,

and not have his scare for nothin'; so he says to him,

`What do you want, now you hev come?'

“The man he didn't speak; he only sort o' moaned,

and p'inted to the chimbley. He seemed to try to

speak, but couldn't; for ye see it isn't often that his

sort o' folks is permitted to speak: but just then

there came a screechin' blast o' wind, and blowed the

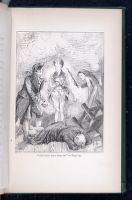

“Old Cack knew him too.”—Page 20.

[Description: 703EAF. Illustration page. Image of a man lying face down on the floor next to an overturned chair and a spilled glass of liquid. Three figure are standing behing him. One is a hunched woman wielding a stick. The second is a man with his arm crossed over his chest and his hair standing straight up. The third is a man looking confused. There is a great deal of billowing smoke in the background.]

into the room, and there seemed to be a whirlwind and

darkness and moans and screeches; and, when it all

cleared up, Ketury and the man was both gone, and

only old Cack lay on the ground, rolling and moaning

as if he'd die.

“Wal, Cap'n Eb he picked him up, and built up

the fire, and sort o' comforted him up, 'cause the crittur

was in distress o' mind that was drefful. The

awful Providence, ye see, had awakened him, and his

sin had been set home to his soul; and he was under

such conviction, that it all had to come out, — how

old Cack's father had murdered poor Lommedieu for

his money, and Cack had been privy to it, and helped

his father build the body up in that very chimbley;

and he said that he hadn't had neither peace nor rest

since then, and that was what had driv' him away

from ordinances; for ye know sinnin' will always

make a man leave prayin'. Wal, Cack didn't live

but a day or two. Cap'n Eb he got the minister o'

Sherburn and one o' the selectmen down to see him;

and they took his deposition. He seemed railly quite

penitent; and Parson Carryl he prayed with him, and

soul: and so, at the eleventh hour, poor old Cack might

have got in; at least it looks a leetle like it. He was

distressed to think he couldn't live to be hung. He

sort o' seemed to think, that if he was fairly tried, and

hung, it would make it all square. He made Parson

Carryl promise to have the old mill pulled down, and

bury the body; and, after he was dead, they did it.

“Cap'n Eb he was one of a party o' eight that

pulled down the chimbley; and there, sure enough,

was the skeleton of poor Lommedieu.

“So there you see, boys, there can't be no iniquity

so hid but what it'll come out. The wild Indians of

the forest, and the stormy winds and tempests, j'ined

together to bring out this 'ere.”

“For my part,” said Aunt Lois sharply, “I never

believed that story.”

“Why, Lois,” said my grandmother, “Cap'n Eb

Sawin was a regular church-member, and a most respectable

man.”

“Law, mother! I don't doubt he thought so. I

suppose he and Cack got drinking toddy together, till

he got asleep, and dreamed it. I wouldn't believe

and eyes. I should only think I was crazy, that's all.”

“Come, Lois, if I was you, I wouldn't talk so like

a Sadducee,” said my grandmother. “What would

become of all the accounts in Dr. Cotton Mather's

`Magnilly' if folks were like you?”

“Wal,” said Sam Lawson, drooping contemplatively

over the coals, and gazing into the fire, “there's a

putty consid'able sight o' things in this world that's

true; and then ag'in there's a sight o' things that

ain't true. Now, my old gran'ther used to say, `Boys,

says he, `if ye want to lead a pleasant and prosperous

life, ye must contrive allers to keep jest the happy

medium between truth and falsehood.' Now, that

are's my doctrine.”

Aunt Lois knit severely.

“Boys,” said Sam, “don't you want ter go down

with me and get a mug o' cider?”

Of course we did, and took down a basket to bring

up some apples to roast.

“Boys,” says Sam mysteriously, while he was

drawing the cider, “you jest ask your Aunt Lois to

tell you what she knows 'bout Ruth Sullivan.”

“Why, what is it?”

“Oh! you must ask her. These 'ere folks that's so

kind o' toppin' about sperits and sich, come sift 'em

down, you gen'lly find they knows one story that kind

o' puzzles 'em. Now you mind, and jist ask your

Aunt Lois about Ruth Sullivan.”

| Sam Lawson's Oldtown fireside stories | ||