| Sam Lawson's Oldtown fireside stories | ||

THE BULL-FIGHT.

IT was Saturday afternoon, — time of

blessed memory to boys, — and we were

free for a ramble after huckleberries;

and, with our pails in hand, were making

the best of our way to a noted spot

where that fruit was most abundant.

Sam was with us, his long legs striding over the

ground at a rate that kept us on a brisk trot, though

he himself was only lounging leisurely, with his

usual air of contemplation.

“Look 'ere, boys,” he suddenly said, pausing and

resting his elbow on the top of a rail-fence, “we

shall jest hev to go back and go round by Deakin

Blodgett's barn.”

“Why so?” we both burst forth in eager tones.

“Wal, don't ye see the deakin's turned in his

bull into this 'ere lot?”

“Who cares?” said I. “I ain't afraid.”

“Nor I,” said Harry. “Look at him: he looks

mild enough: he won't hurt us.”

“Not as you knows on,” said Sam; “and then,

agin, you don't know, — nobody never knows, what

one o' them 'ere critters will do: they's jest the most

contrary critters; and ef you think they're goin' to

do one way they're sure to do t'other. I could tell ye

a story now that'd jest make yer har stan' on eend.”

Of course we wanted to have our hair stand on

end, and beset Sam for the story; but he hung off.

“Lordy massy! boys, jest let's wait till ye've got yer

huckleberries: yer granny won't like it ef ye don't

bring her none, and Hepsy she'll be in my har, —

what's left on't,” said Sam, taking off his old torn

hat, and rubbing the loose shock of brash and grizzled

hair.

So we turned and made a détour, leaving the bull

on the right, though we longed amazingly to have a

bout with him, for the fun of the thing, and mentally

resolved to try it when our mentor was not round.

It all comes back to me again, — the image of that

huckleberry-pasture, interwoven with fragrance of

sweet-fern, and the ground under our feet embroidered

with star-moss and wintergreen, or foamy patches of

mossy frost-work, that crushed and crackled delightfully

beneath our feet. Every now and then a tall,

straight fire-lily — black, spotted in its centre — rose

like a little jet of flame; and we gathered it eagerly,

though the fierce August sun wilted it in our hands.

The huckleberry-bushes, bending under their purple

weight, we gathered in large armfuls, and took them

under the shadow of the pine-trees, that we might

strip them at our leisure, without being scorched by

the intense glare of the sun. Armful after armful

we carried and deposited in the shade, and then sat

down to the task of picking them off into our pails.

It was one of those New-England days hotter than

the tropics. Not a breath of air was stirring, not a

bird sang a note, not a sound was heard, except the

drowsy grating of the locusts.

“Well, now, Sam, now tell us that story about

the bull.”

“Lordy massy, how hot 'tis!” said Sam, lying

hands folded under his head. “I'm all in a drip of

sweat.”

“Well, Sam, we'll pick off your berries, if you'll

talk.”

“Wall, wall, be kerful yer don't git no green

ones in among 'em, else Hepsy 'll be down on me.

She's drefful partikelar, she is. Every thing has to

be jest so. Ef it ain't, you'll hear on't. Lordy

massy! boys, she's always telling me I don't do nothin'

for the support of the family. I leave it to you

if I didn't ketch her a nice mess o' fish a Tuesday.

I tell her folks can't expect to roll in money, and

allers to have every thing jess 'z they want it. We

brought nothin' into the world with us, and it's

sartain we ken carry nothin' out; and, having food

and raiment, we ought to be content. We have

ben better off'n we be now. Why, boys, I've seen

the time that I've spent thirty-seven cents a week

for nutmegs; but Hepsy hain't no gratitude: such

folks hez to be brought down. Take care, now, yer

ain't a-putting green ones in; be yer?”

“Sam, we sha'n't put in any at all, if you don't

tell us that story.”

“Lordy massy! you young ones, there ain't never

no contentin' yer, ef a fellow was to talk to the millennium.

Wonder now if there is going to be any

millennium. Wish I'd waited, and been born in

them days, 'spect things would a sorter come along

easier. Wall, I shall git through some way, I

s'pose.”

“Sam,” said I, sitting back, “we're putting all our

berries into your pail; and, if you don't begin to tell

us a story, we won't do it.”

“Lordy massy! boys, I'm kind o' collectin' my

idees. Ye have to talk a while to git a-goin',

everybody does. Wal, about this 'ere story. Ye

'member that old brown house, up on the hill there,

that we saw when we come round the corner?

That 'are was where old Mump Moss used to live.

Old Mump was consid'able of a nice man: he took

in Ike Sanders, Mis' Moss's sister's boy, to help him

on the farm, and did by him pretty much ez he did

by his own. Bill Moss, Mump's boy, he was a contrairy

kind o' critter, and he was allers a-hectorin'

Ike. He was allers puttin' off the heaviest end of

every thing on to him. He'd shirk his work, and git

threw it up at him that he was eatin' his father's

bread; and he watched every mouthful he ate, as if

he hated to see it go down. Wal, ye see, for all that,

Ike he growed up tall and strong, and a real handsome

young feller; and everybody liked him. And Bill he

was so gritty and contrairy, that his own mother and

sisters couldn't stan' him; and he was allers a-flingin'

it up at 'em that they liked Ike more'n they did him.

Finally his mother she said to him one day, `Why

shouldn't I,' sez she, `when Ike's allers pleasant to

me, and doin' every thing he ken fur me, and you

don't do nothin' but scold.' That 'are, you see, was

a kind o' home-thrust, and Bill he didn't like Ike a

bit the better for that. He did every thing he could

to plague him, and hector him, and sarcumvent him,

and set people agin him.

“Wal, ye see, 'twas the old story about Jacob and

Laban over agin. Every thing that Ike put his

hand to kind o' prospered. Everybody liked him,

everybody hed a good word for him, everybody

helped grease his wheels. Wal, come time when

he was twenty-one, old Mump he gin him a settin'-out.

he gin him a good cow, and Mis' Moss she knit

him up a lot o' stockings, and the gals they made him

up his shirts. Then, Ike he got a place with Squire

Wells, and got good wages; and he bought a little

bit o' land, with a house on it, on Squire Wells's

place, and took a mortgage on't, to work off. He

used to work his own land, late at night and early

in the mornin', over and above givin' good days'

works to the squire; and the old squire he sot all

the world by him, and said he hedn't hed sich a man

to work since he didn't know when.

“Wal, a body might ha' thought that when Bill had

a got him out o' the house, he might ha' ben satisfied,

but he wasn't. He was an ugly fellow, Bill Moss

was; and a body would ha' thought that every thing

good that happened to Ike was jest so much took

from him. Come to be young men, growed up together,

and waitin' on the gals round, Ike he was

pretty apt to cut Bill out. Yer see, though Bill was

goin' to have the farm, and all old Mump's money,

he warn't pleasant-spoken; and so, when the gals

got a chance, they'd allers rather go with Ike than

about the handsomest girl there was round, and

she hed all the fellers arter her; and her way was

to speak 'em all fair, and keep 'em all sort o' waitin'

and hopin', till she got ready to make her mind up.

She'd entertain Bill Saturday night, and she'd tell

Ike he might come Sunday night; and so Ike he was

well pleased, and Bill he growled.

“Wal, there come along a gret cattle-show.

Squire Wells he got it up: it was to be the gretest

kind of a time, and Squire Wells he give money

fur prizes. There was to be a prize on the best

cow, and the best bull, and the best ox, and the

best horse, and the biggest punkins and squashes

and beets, and there was a prize for the best loaf o'

bread, and the best pair o' stockin's, and the handsomest

bed-quilt, and the rest o' women's work.

Wal, yer see, there was a gret to-do about the

cattle-show; and the wagons they came in from all

around, — ten miles; and the gals all dressed up in

their best bunnits, and they had a ball in the evenin'.

Wal, ye see, it so happened that Bill and Ike each

on 'em sent a bull to the cattle-show; and Ike's bull

He was jest about as much riled as a feller could be;

and that evenin' Delily she danced with Ike twice as

many times ez she did with him. Wal, Bill he got

it round among the fellers that the jedges hed been

partial; and he said, if them bulls was put together,

his bull would whip Ike's all to thunder. Wal, the

fellers thought 'twould be kind o' fun to try 'em, and

they put Ike up to it. And finally 'twas agreed that

Ike's bull should be driv over to old Mump's; and

the Monday after the cattle-show, they should let

'em out into the meadow together and see which

was the strongest. So there was a Sunday the bulls

they were both put up together in the same barn;

and the 'greement was, they wasn't to be looked at

nor touched till the time come to turn 'em out.

“Come Sunday mornin', they got up the wagon to

go to meetin'; and Mis' Moss and the gals and old

Mump, they was all ready; and the old yaller dog he

was standin' waitin' by the wagon, and Bill warn't

nowhere to be found. So they sent one o' the girls

up chamber to see what'd got him; and there he was

a-lyin' on the bed, and said he'd got a drefful headache,

the second bell was a-tollin', and they had to drive

off without him: they never mistrusted but what

'twas jest so. Wal, yer see, boys, 'twas that 'are kind

o' Sunday headache that sort o' gets better when the

folks is all fairly into meetin'. So, when the wagon

was fairly out o' sight, Bill he thought he'd jest go

and have a peek at them bulls. Wal, he looked and

he peeked, and finally he thought they looked so

sort o' innocent 'twouldn't do no harm to jest let 'em

have a little run in the cow-yard aforehand. He

kind o' wanted to see how they was likely to cut up.

Now, ye see, the mischief about bulls is, that a body

never knows what they's goin' to do, 'cause whatever

notion takes 'em allers comes into their heads so

kind o' sudden, and it's jest a word and a blow with

'em. Wal, so fust he let out his bull, and then he

went in and let out Ike's. Wal, the very fust thing

that critter did he run up to Bill's bull, full tilt, and

jest gin one rip with his horns right in the side of

him, and knocked him over and killed him. Didn't

die right off, but he was done for; and Bill he gin a

yell, and run right up and hit him with a stick, and

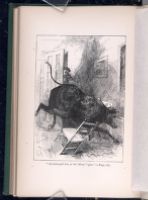

“He bethought him of old Mump's gun.”—Page 187.

[Description: 703EAF. Illustration page. Image of a bull in a room. The bull is bucking and is knocking over a chair. A man is peering around a door with a shotgun aimed at the bull.]

I tell you, Bill he turned and made a straight coat-tail,

rippin' and peelin' it towards the house, and the

bull tearin' on right arter him. Into the kitchen he

went, and he hedn't no time to shut the door, and

the bull arter him; and into the keepin'-room, and

the bull arter him there. And he hedn't but jest

time to git up the chamber-stairs, when he heard the

old feller roarin' and tearin' round there like all natur.

Fust he went to the lookin'-glass, and smashed

that all to pieces. Then he histed the table over,

and he rattled and smashed the chairs round, and made

such a roarin' and noise, ye'd ha' thought there was

seven devils there; and in the midst of it Bill he

looked out of the window, and see the wagon

a-comin' back; and `Lordy massy!' he thought to

himself, `the bull 'll kill every one on 'em,' and he

run to the window and yelled and shouted, and they

saw him, and thought the house must be afire.

Finally, he bethought him of old Mump's gun, and

he run round and got it, and poked it through a

crack of the chamber-door, and fired off bang! and

shot him dead, jest as Mis' Moss and the girls was

comin' into the kitchen-door.

“Wal, there was, to be sure, the 'bomination o'

desolation when they come in and found every thing

all up in a heap and broke to pieces, and the old

critter a-kickin' and bleedin' all over the carpet, and

Bill as pale as his shirt-tail on the chamber-stairs.

They had an awful mess on't; and there was the two

bulls dead and to be took care uv.

“`Wal, Bill,” said his father, “I hope yer satisfied

now. All that comes o' stayin' to home from

meetin', and keepin' temporal things in yer head all

day Sunday. You've lost your own bull, you've got

Ike's to pay for, and ye'll have the laugh on yer all

round the country.'

“`I expect, father, we ken corn the meat,' says

Mis' Moss, `and maybe the hide'll sell for something,'

sez she; for she felt kind o' tender for Bill,

and didn't want to bear down too hard on him.

“Wal, the story got round, and everybody was

a-throwin' it up at Bill; and Delily, in partikelar,

hectored him about it till he wished the bulls had been

in the Red Sea afore he'd ever seen one on 'em.

Wal, it really driv him out o' town, and he went off

out West to settle, and nobody missed him much;

to better, till now they own jest about as pretty

a farm as there is round. Yer remember that white

house with green blinds, that we passed when we

was goin' to the trout-brook? Wal, that 'ere's the

one.”

| Sam Lawson's Oldtown fireside stories | ||