| Sam Lawson's Oldtown fireside stories | ||

THE MINISTER'S HOUSEKEEPER.

Scene. — The shady side of a blueberry-pasture. — Sam Lawson with the boys,

picking blueberries. — Sam, loq.

WAL, you see, boys, 'twas just here, —

Parson Carryl's wife, she died along

in the forepart o' March: my cousin

Huldy, she undertook to keep house

for him. The way on't was, that

Huldy, she went to take care o' Mis'

Carryl in the fust on't, when she

fust took sick. Huldy was a tailoress by trade; but

then she was one o' these 'ere facultised persons that

has a gift for most any thing, and that was how Mis'

Carryl come to set sech store by her, that, when she

was sick, nothin' would do for her but she must have

Huldy round all the time: and the minister, he said

shouldn't lose nothin' by it. And so Huldy, she staid

with Mis' Carryl full three months afore she died,

and got to seein' to every thing pretty much round

the place.

“Wal, arter Mis' Carryl died, Parson Carryl, he'd

got so kind o' used to hevin' on her 'round, takin'

care o' things, that he wanted her to stay along a

spell; and so Huldy, she staid along a spell, and

poured out his tea, and mended his close, and made

pies and cakes, and cooked and washed and ironed,

and kep' every thing as neat as a pin. Huldy was a

drefful chipper sort o' gal; and work sort o' rolled off

from her like water off a duck's back. There warn't

no gal in Sherburne that could put sich a sight o'

work through as Huldy; and yet, Sunday mornin',

she always come out in the singers' seat like one o'

these 'ere June roses, lookin' so fresh and smilin',

and her voice was jest as clear and sweet as a

meadow lark's — Lordy massy! I 'member how she

used to sing some o' them 'are places where the

treble and counter used to go together: her voice

kind o' trembled a little, and it sort o' went

lived!”

Here Sam leaned contemplatively back with his

head in a clump of sweet fern, and refreshed himself

with a chew of young wintergreen. “This 'ere

young wintergreen, boys, is jest like a feller's

thoughts o' things that happened when he was

young: it comes up jest so fresh and tender every

year, the longest time you hev to live; and you can't

help chawin' on't tho' 'tis sort o' stingin'. I don't

never get over likin' young wintergreen.”

“But about Huldah, Sam?”

“Oh, yes! about Huldy. Lordy massy! when a

feller is Indianin' round, these 'ere pleasant summer

days, a feller's thoughts gits like a flock o' young

partridges: they's up and down and everywhere;

'cause one place is jest about as good as another,

when they's all so kind o' comfortable and nice.

Wal, about Huldy, — as I was a sayin'. She was

jest as handsome a gal to look at as a feller could

have; and I think a nice, well-behaved young gal in

the singers' seat of a Sunday is a means o' grace: it's

sort o' drawin' to the unregenerate, you know.

to Sherburne of a Sunday mornin', jest to play the

bass-viol in the same singers' seat with Huldy. She

was very much respected, Huldy was; and, when she

went out to tailorin', she was allers bespoke six

months ahead, and sent for in waggins up and down

for ten miles round; for the young fellers was allers

'mazin' anxious to be sent after Huldy, and was

quite free to offer to go for her. Wal, after Mis'

Carryl died, Huldy got to be sort o' housekeeper

at the minister's, and saw to every thing, and did

every thing: so that there warn't a pin out o' the

way.

“But you know how 'tis in parishes: there allers is

women that thinks the minister's affairs belongs to

them, and they ought to have the rulin' and guidin'

of 'em; and, if a minister's wife dies, there's folks

that allers has their eyes open on providences, —

lookin' out who's to be the next one.

“Now, there was Mis' Amaziah Pipperidge, a widder

with snappin' black eyes, and a hook nose, — kind o'

like a hawk; and she was one o' them up-and-down

commandin' sort o' women, that feel that they have a

parish, and 'specially to the minister.

“Folks did say that Mis' Pipperidge sort o' sot her

eye on the parson for herself: wal, now that 'are

might a been, or it might not. Some folks thought

it was a very suitable connection. You see she hed a

good property of her own, right night to the minister's

lot, and was allers kind o' active and busy; so, takin'

one thing with another, I shouldn't wonder if Mis'

Pipperidge should a thought that Providence p'inted

that way. At any rate, she went up to Deakin Blodgett's

wife, and they two sort o' put their heads

together a mournin' and condolin' about the way

things was likely to go on at the minister's now Mis'

Carryl was dead. Ye see, the parson's wife, she was

one of them women who hed their eyes everywhere

and on every thing. She was a little thin woman,

but tough as Inger rubber, and smart as a steel trap;

and there warn't a hen laid an egg, or cackled, but Mis'

Carryl was right there to see about it; and she hed

the garden made in the spring, and the medders

mowed in summer, and the cider made, and the corn

husked, and the apples got in the fall; and the doctor,

on Jerusalem and Jericho and them things that

ministers think about. But Lordy massy! he didn't

know nothin' about where any thing he eat or drunk

or wore come from or went to: his wife jest led

him 'round in temporal things and took care on him

like a baby.

“Wal, to be sure, Mis' Carryl looked up to him

in spirituals, and thought all the world on him; for

there warn't a smarter minister no where 'round.

Why, when he preached on decrees and election,

they used to come clear over from South Parish, and

West Sherburne, and Old Town to hear him; and

there was sich a row o' waggins tied along by the

meetin'-house that the stables was all full, and all

the hitchin'-posts was full clean up to the tavern, so

that folks said the doctor made the town look like a

gineral trainin'-day a Sunday.

“He was gret on texts, the doctor was. When

he hed a p'int to prove, he'd jest go thro' the Bible,

and drive all the texts ahead o' him like a flock o'

sheep; and then, if there was a text that seemed

agin him, why, he'd come out with his Greek and

see a fellar chase a contrary bell-wether, and make

him jump the fence arter the rest. I tell you, there

wa'n't no text in the Bible that could stand agin the

doctor when his blood was up. The year arter the

doctor was app'inted to preach the 'lection sermon

in Boston, he made such a figger that the Brattlestreet

Church sent a committee right down to see if

they couldn't get him to Boston; and then the Sherburne

folks, they up and raised his salary; ye see,

there ain't nothin' wakes folks up like somebody

else's wantin' what you've got. Wal, that fall they

made him a Doctor o' Divinity at Cambridge College,

and so they sot more by him than ever. Wal, you

see, the doctor, of course he felt kind o' lonesome

and afflicted when Mis' Carryl was gone; but railly

and truly, Huldy was so up to every thing about

house, that the doctor didn't miss nothin' in a temporal

way. His shirt-bosoms was pleated finer

than they ever was, and them ruffles 'round his

wrists was kep' like the driven snow; and there

warn't a brack in his silk stockin's, and his shoe

buckles was kep' polished up, and his coats brushed;

Huldy's; and her butter was like solid lumps o' gold;

and there wern't no pies to equal hers; and so the

doctor never felt the loss o' Miss Carryl at table.

Then there was Huldy allers oppisite to him, with

her blue eyes and her cheeks like two fresh peaches.

She was kind o' pleasant to look at; and the more the

doctor looked at her the better he liked her; and so

things seemed to be goin' on quite quiet and comfortable

ef it hadn't been that Mis' Pipperidge and

Mis' Deakin Blodgett and Mis' Sawin got their

heads together a talkin' about things.

“`Poor man,' says Mis' Pipperidge, `what can that

child that he's got there do towards takin' the care

of all that place? It takes a mature woman,' she

says, `to tread in Mis' Carryl's shoes.'

“`That it does,' said Mis' Blodgett; `and, when

things once get to runnin' down hill, there ain't no

stoppin' on 'em,' says she.

“Then Mis' Sawin she took it up. (Ye see, Mis'

Sawin used to go out to dress-makin', and was sort o'

jealous, 'cause folks sot more by Huldy than they

did by her). `Well,' says she, `Huldy Peters is

I do say I never did believe in her way o' makin' button-holes;

and I must say, if 'twas the dearest friend

I hed, that I thought Huldy tryin' to fit Mis' Kittridge's

plumb-colored silk was a clear piece o' presumption;

the silk was jist spiled, so 'twarn't fit to

come into the meetin'-house. I must say, Huldy's a

gal that's always too ventersome about takin' 'sponsibilities

she don't know nothin' about.'

“`Of course she don't,' said Mis' Deakin Blodgett.

`What does she know about all the lookin' and seein'

to that there ought to be in guidin' the minister's

house. Huldy's well meanin', and she's good at her

work, and good in the singers' seat; but Lordy massy!

she hain't got no experience. Parson Carryl ought

to have an experienced woman to keep house for him.

There's the spring house-cleanin' and the fall house-cleanin'

to be seen to, and the things to be put

away from the moths; and then the gettin' ready

for the association and all the ministers' meetin's;

and the makin' the soap and the candles, and settin'

the hens and turkeys, watchin' the calves, and seein'

after the hired men and the garden; and there

and has nobody 'round but that 'are gal, and don't

even know how things must be a runnin' to waste!'

“Wal, the upshot on't was, they fussed and fuzzled

and wuzzled till they'd drinked up all the tea in the teapot;

and then they went down and called on the parson,

and wuzzled him all up talkin' about this, that,

and t'other that wanted lookin' to, and that it was no

way to leave every thing to a young chit like Huldy,

and that he ought to be lookin' about for an experienced

woman. The parson he thanked 'em kindly,

and said he believed their motives was good, but he

didn't go no further. He didn't ask Mis' Pipperidge

to come and stay there and help him, nor nothin' o'

that kind; but he said he'd attend to matters himself.

The fact was, the parson had got such a likin' for

havin' Huldy 'round, that he couldn't think o' such a

thing as swappin' her off for the Widder Pipperidge.

“But he thought to himself, `Huldy is a good girl;

but I oughtn't to be a leavin' every thing to her, — it's

too hard on her. I ought to be instructin' and guidin'

and helpin' of her; 'cause 'tain't everybody could be

expected to know and do what Mis' Carryl did;' and

a time on't when the minister began to come out of

his study, and want to tew 'round and see to things?

Huldy, you see, thought all the world of the minister,

and she was 'most afraid to laugh; but she told

me she couldn't, for the life of her, help it when his

back was turned, for he wuzzled things up in the

most singular way. But Huldy she'd jest say `Yes,

sir,' and get him off into his study, and go on her

own way.

“`Huldy,' says the minister one day, `you ain't experienced

out doors; and, when you want to know

any thing, you must come to me.'

“`Yes, sir,' says Huldy.

“`Now, Huldy,' says the parson, `you must be sure

to save the turkey-eggs, so that we can have a lot of

turkeys for Thanksgiving.'

“`Yes, sir,' says Huldy; and she opened the pantry-door,

and showed him a nice dishful she'd been a savin'

up. Wal, the very next day the parson's hen-turkey

was found killed up to old Jim Scroggs's barn.

Folks said Scroggs killed it; though Scroggs, he stood

to it he didn't: at any rate, the Scroggses, they made

she'd set her heart on raisin' the turkeys; and says

she, `Oh, dear! I don't know what I shall do. I was

just ready to see her.'

“`Do, Huldy?” says the parson: `why, there's the

other turkey, out there by the door; and a fine bird,

too, he is.'

Sure enough, there was the old tom-turkey a

struttin' and a sidlin' and a quitterin,' and a floutin'

his tail-feathers in the sun, like a lively young widower,

all ready to begin life over agin.

“`But,' says Huldy, `you know he can't set on

eggs.'

“`He can't? I'd like to know why,' says the parson.

`He shall set on eggs, and hatch 'em too.'

“`O doctor!' says Huldy, all in a tremble; 'cause,

you know, she didn't want to contradict the minister,

and she was afraid she should laugh, — `I never

heard that a tom-turkey would set on eggs.'

“`Why, they ought to,' said the parson, getting

quite 'arnest: `what else be they good for? you

just bring out the eggs, now, and put 'em in the nest,

and I'll make him set on 'em.'

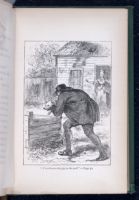

“So Huldy she thought there wern't no way to convince

him but to let him try: so she took the eggs

out, and fixed 'em all nice in the nest; and then she

come back and found old Tom a skirmishin' with the

parson pretty lively, I tell ye. Ye see, old Tom he

didn't take the idee at all; and he flopped and gobbled,

and fit the parson; and the parson's wig got 'round

so that his cue stuck straight out over his ear, but

he'd got his blood up. Ye see, the old doctor was

used to carryin' his p'ints o' doctrine; and he hadn't

fit the Arminians and Socinians to be beat by a tom-turkey;

so finally he made a dive, and ketched him

by the neck in spite o' his floppin', and stroked him

down, and put Huldy's apron 'round him.

“`There, Huldy,' he says, quite red in the face,

`we've got him now;' and he travelled off to the

barn with him as lively as a cricket.

“Huldy came behind jist chokin' with laugh, and

afraid the minister would look 'round and see her.

“`Now, Huldy, we'll crook his legs, and set him

down,' says the parson, when they got him to the

nest: `you see he is getting quiet, and he'll set there

all right.'

“And the parson, he sot him down; and old Tom he

sot there solemn enough, and held his head down all

droopin', lookin' like a rail pious old cock, as long as

the parson sot by him.

“`There: you see how still he sets,' says the parson

to Huldy.

“Huldy was 'most dyin' for fear she should laugh.

`I'm afraid he'll get up,' says she, `when you

do.'

“`Oh, no, he won't!' says the parson, quite confident.

`There, there,' says he, layin' his hands on him, as if

pronouncin' a blessin'. But when the parson riz up,

old Tom he riz up too, and began to march over the

eggs.

“`Stop, now!' says the parson. `I'll make him get

down agin: hand me that corn-basket; we'll put

that over him.'

“So he crooked old Tom's legs, and got him down

agin; and they put the corn-basket over him, and

then they both stood and waited.

“`That'll do the thing, Huldy,' said the parson.

“`I don't know about it,' says Huldy.

“`Oh, yes, it will, child! I understand,' says he.

“Just as he spoke, the basket riz right up and stood,

and they could see old Tom's long legs.

“`I'll make him stay down, confound him,' says

the parson; for, ye see, parsons is men, like the rest

on us, and the doctor had got his spunk up.

“`You jist hold him a minute, and I'll get something

that'll make him stay, I guess;' and out he

went to the fence, and brought in a long, thin, flat

stone, and laid it on old Tom's back.

“Old Tom he wilted down considerable under

this, and looked railly as if he was goin' to give in.

He staid still there a good long spell, and the minister

and Huldy left him there and come up to the

house; but they hadn't more than got in the door

before they see old Tom a hippin' along, as high-steppin'

as ever, sayin' `Talk! talk! and quitter!

quitter!' and struttin' and gobblin' as if he'd come

through the Red Sea, and got the victory.

“`Oh, my eggs!' says Huldy. `I'm afraid he's

smashed 'em!'

“And sure enough, there they was, smashed flat

enough under the stone.

“`I'll have him killed,' said the parson: `we

won't have such a critter 'round.'

“But the parson, he slep' on't, and then didn't do

it: he only come out next Sunday with a tip-top

sermon on the `'Riginal Cuss' that was pronounced

on things in gineral, when Adam fell, and showed

how every thing was allowed to go contrary ever

since. There was pig-weed, and pusley, and Canady

thistles, cut-worms, and bag-worms, and canker-worms,

to say nothin' of rattlesnakes. The doctor

made it very impressive and sort o' improvin'; but

Huldy, she told me, goin' home, that she hardly

could keep from laughin' two or three times in the

sermon when she thought of old Tom a standin' up

with the corn-basket on his back.

“Wal, next week Huldy she jist borrowed the minister's

horse and side-saddle, and rode over to South

Parish to her Aunt Bascome's, — Widder Bascome's,

you know, that lives there by the trout-brook, — and

got a lot o' turkey-eggs o' her, and come back and set

a hen on 'em, and said nothin'; and in good time there

was as nice a lot o' turkey-chicks as ever ye see.

“Huldy never said a word to the minister about his

experiment, and he never said a word to her; but he

sort o' kep' more to his books, and didn't take it on

him to advise so much.

“But not long arter he took it into his head that

Huldy ought to have a pig to be a fattin' with the

buttermilk. Mis' Pipperidge set him up to it; and

jist then old Tim Bigelow, out to Juniper Hill, told

him if he'd call over he'd give him a little pig.

“So he sent for a man, and told him to build a pig-pen

right out by the well, and have it all ready when

he came home with his pig.

“Huldy she said she wished he might put a curb

round the well out there, because in the dark, sometimes,

a body might stumble into it; and the parson,

he told him he might do that.

“Wal, old Aikin, the carpenter, he didn't come till

most the middle of the arternoon; and then he sort o'

idled, so that he didn't get up the well-curb till sundown;

and then he went off and said he'd come and

do the pig-pen next day.

“Wal, arter dark, Parson Carryl he driv into the

yard, full chizel, with his pig. He'd tied up his

mouth to keep him from squeelin'; and he see what

he thought was the pig-pen, — he was rather nearsighted,

— and so he ran and threw piggy over; and

down he dropped into the water, and the minister

quite delighted.

“`There, Huldy, I've got you a nice little pig.'

“`Dear me!' says Huldy: `where have you put

him?'

“`Why, out there in the pig-pen, to be sure.'

“`Oh, dear me!' says Huldy: `that's the well-curb;

there ain't no pig-pen built,' says she.

“`Lordy massy!' says the parson: `then I've

thrown the pig in the well!'

“Wal, Huldy she worked and worked, and finally

she fished piggy out in the bucket, but he was dead

as a door-nail; and she got him out o' the way

quietly, and didn't say much; and the parson, he took

to a great Hebrew book in his study; and says he,

`Huldy, I ain't much in temporals,' says he. Huldy

says she kind o' felt her heart go out to him, he was

so sort o' meek and helpless and larned; and says she,

`Wal, Parson Carryl, don't trouble your head no

more about it; I'll see to things;' and sure enough,

a week arter there was a nice pen, all ship-shape, and

two little white pigs that Huldy bought with the

money for the butter she sold at the store.

“`Wal, Huldy,' said the parson, `you are a most

amazin' child: you don't say nothin', but you do

more than most folks.'

“Arter that the parson set sich store by Huldy that

he come to her and asked her about every thing, and

it was amazin' how every thing she put her hand to

prospered. Huldy planted marigolds and larkspurs,

pinks and carnations, all up and down the path to the

front door, and trained up mornin' glories and scarlet-runners

round the windows. And she was always

a gettin' a root here, and a sprig there, and a seed

from somebody else: for Huldy was one o' them that

has the gift, so that ef you jist give 'em the leastest

sprig of any thing they make a great bush out of it

right away; so that in six months Huldy had roses

and geraniums and lilies, sich as it would a took a

gardener to raise. The parson, he took no notice at

fust; but when the yard was all ablaze with flowers he

used to come and stand in a kind o' maze at the front

door, and say, `Beautiful, beautiful: why, Huldy,

I never see any thing like it.' And then when her

work was done arternoons, Huldy would sit with her

sewin' in the porch, and sing and trill away till she'd

orioles to answer her, and the great big elm-tree

overhead would get perfectly rackety with the birds;

and the parson, settin' there in his study, would git

to kind o' dreamin' about the angels, and golden

harps, and the New Jerusalem; but he wouldn't

speak a word, 'cause Huldy she was jist like them

wood-thrushes, she never could sing so well when

she thought folks was hearin'. Folks noticed, about

this time, that the parson's sermons got to be like

Aaron's rod, that budded and blossomed: there was

things in 'em about flowers and birds, and more 'special

about the music o' heaven. And Huldy she

noticed, that ef there was a hymn run in her head

while she was 'round a workin' the minister was

sure to give it out next Sunday. You see, Huldy

was jist like a bee: she always sung when she was

workin', and you could hear her trillin', now down

in the corn-patch, while she was pickin' the corn;

and now in the buttery, while she was workin' the

butter; and now she'd go singin' down cellar, and

then she'd be singin' up over head, so that she

seemed to fill a house chock full o' music.

“Huldy was so sort o' chipper and fair spoken, that

she got the hired men all under her thumb: they

come to her and took her orders jist as meek as so

many calves; and she traded at the store, and kep'

the accounts, and she hed her eyes everywhere, and

tied up all the ends so tight that there want no gettin'

'round her. She wouldn't let nobody put nothin'

off on Parson Carryl, 'cause he was a minister. Huldy

was allers up to anybody that wanted to make a

hard bargain; and, afore he knew jist what he was

about, she'd got the best end of it, and everybody

said that Huldy was the most capable gal that they'd

ever traded with.

“Wal, come to the meetin' of the Association, Mis'

Deakin Blodgett and Mis' Pipperidge come callin' up

to the parson's, all in a stew, and offerin' their services

to get the house ready; but the doctor, he jist

thanked 'em quite quiet, and turned 'em over to Huldy;

and Huldy she told 'em that she'd got every

thing ready, and showed 'em her pantries, and her

cakes and her pies and her puddin's, and took 'em

all over the house; and they went peekin' and pokin',

openin' cupboard-doors, and lookin' into drawers; and

way, from garret to cellar, and so they went off quite

discontented. Arter that the women set a new

trouble a brewin'. Then they begun to talk that it

was a year now since Mis' Carryl died; and it r'ally

wasn't proper such a young gal to be stayin' there,

who everybody could see was a settin' her cap for

the minister.

“Mis' Pipperidge said, that, so long as she looked

on Huldy as the hired gal, she hadn't thought much

about it; but Huldy was railly takin' on airs as an

equal, and appearin' as mistress o' the house in a

way that would make talk if it went on. And Mis'

Pipperidge she driv 'round up to Deakin Abner

Snow's, and down to Mis' 'Lijah Perry's, and asked

them if they wasn't afraid that the way the parson

and Huldy was a goin' on might make talk. And

they said they hadn't thought on't before, but now,

come to think on't, they was sure it would; and they

all went and talked with somebody else, and asked

them if they didn't think it would make talk. So

come Sunday, between meetin's there warn't nothin'

else talked about; and Huldy saw folks a noddin'

to feel drefful sort o' disagreeable. Finally Mis'

Sawin she says to her, `My dear, didn't you, never

think folk would talk about you and the minister?'

“`No: why should they?' says Huldy, quite innocent.

“Wal, dear,' says she, `I think it's a shame; but

they say you're tryin' to catch him, and that it's so

bold and improper for you to be courtin' of him right

in his own house, — you know folks will talk, — I

thought I'd tell you 'cause I think so much of you,'

says she.

“Huldy was a gal of spirit, and she despised the

talk, but it made her drefful uncomfortable; and

when she got home at night she sat down in the mornin'-glory

porch, quite quiet, and didn't sing a word.

“The minister he had heard the same thing from

one of his deakins that day; and, when he saw Huldy

so kind o' silent, he says to her, `Why don't you

sing, my child?'

“He hed a pleasant sort o' way with him, the minister

had, and Huldy had got to likin' to be with him;

and it all come over her that perhaps she ought to go

hardly speak; and, says she, `I can't sing to-night.'

“Says he, `You don't know how much good you're

singin' has done me, nor how much good you have

done me in all ways, Huldy. I wish I knew how to

show my gratitude.'

“`O sir!' says Huldy, `is it improper for me to be

here?'

“`No, dear,' says the minister, `but ill-natured

folks will talk; but there is one way we can stop it,

Huldy — if you will marry me. You'll make me

very happy, and I'll do all I can to make you happy.

Will you?'

“Wal, Huldy never told me jist what she said to

the minister, — gals never does give you the particulars

of them 'are things jist as you'd like 'em, — only I

know the upshot and the hull on't was, that Huldy

she did a consid'able lot o' clear starchin' and ironin'

the next two days; and the Friday o' next week the

minister and she rode over together to Dr. Lothrop's

in Old Town; and the doctor, he jist made 'em man

and wife, `spite of envy of the Jews,' as the hymn

says. Wal, you'd better believe there was a starin'

bell was a tollin', and the minister walked up the

broad aisle with Huldy, all in white, arm in arm

with him, and he opened the minister's pew, and

handed her in as if she was a princess; for, you see,

Parson Carryl come of a good family, and was a

born gentleman, and had a sort o' grand way o' bein'

polite to women-folks. Wal, I guess there was a

rus'lin' among the bunnets. Mis' Pipperidge gin a

great bounce, like corn poppin' on a shovel, and her

eyes glared through her glasses at Huldy as if they'd

a sot her afire; and everybody in the meetin' house

was a starin', I tell yew. But they couldn't none of

'em say nothin' agin Huldy's looks; for there wa'n't

a crimp nor a frill about her that wa'n't jis' so; and

her frock was white as the driven snow, and she had

her bunnet all trimmed up with white ribbins; and

all the fellows said the old doctor had stole a march,

and got the handsomest gal in the parish.

“Wal, arter meetin' they all come 'round the parson

and Huldy at the door, shakin' hands and laughin';

for by that time they was about agreed that

they'd got to let putty well alone.

“`Why, Parson Carryl,' says Mis' Deakin Blodgett,

`how you've come it over us.'

“`Yes,' says the parson, with a kind o' twinkle in

his eye. `I thought,' says he, `as folks wanted to

talk about Huldy and me, I'd give 'em somethin'

wuth talkin' about.'”

| Sam Lawson's Oldtown fireside stories | ||