| Sam Lawson's Oldtown fireside stories | ||

THE GHOST IN THE CAP'N BROWN

HOUSE.

HOW, Sam, tell us certain true, is there

any such things as ghosts?”

“Be there ghosts?” said Sam, immediately

translating into his vernacular

grammar: “wal, now, that are's jest

the question, ye see.”

“Well, grandma thinks there are, and

Aunt Lois thinks it's all nonsense. Why, Aunt Lois

don't even believe the stories in Cotton Mather's

`Magnalia.'”

“Wanter know?” said Sam, with a tone of slow,

languid meditation.

We were sitting on a bank of the Charles River,

fishing. The soft melancholy red of evening was

houses of Oldtown were beginning to loom through

the gloom, solemn and ghostly. There are times

and tones and moods of nature that make all the

vulgar, daily real seem shadowy, vague, and supernatural,

as if the outlines of this hard material present

were fading into the invisible and unknown. So

Oldtown, with its elm-trees, its great square white

houses, its meeting-house and tavern and blacksmith's

shop and mill, which at high noon seem as

real and as commonplace as possible, at this hour of

the evening were dreamy and solemn. They rose up

blurred, indistinct, dark; here and there winking

candles sent long lines of light through the shadows,

and little drops of unforeseen rain rippled the sheeny

darkness of the water.

“Wal, you see, boys, in them things it's jest as

well to mind your granny. There's a consid'able

sight o' gumption in grandmas. You look at the

folks that's allus tellin' you what they don't believe,

— they don't believe this, and they don't believe

that, — and what sort o' folks is they? Why, like

yer Aunt Lois, sort o' stringy and dry. There ain't

no 'sorption got out o' not believin' nothin'.

“Lord a massy! we don't know nothin' 'bout them

things. We hain't ben there, and can't say that

there ain't no ghosts and sich; can we, now?”

We agreed to that fact, and sat a little closer to

Sam in the gathering gloom.

“Tell us about the Cap'n Brown house, Sam.”

“Ye didn't never go over the Cap'n Brown

house?”

No, we had not that advantage.

“Wal, yer see, Cap'n Brown he made all his

money to sea, in furrin parts, and then come here to

Oldtown to settle down.

“Now, there ain't no knowin' 'bout these 'ere old

ship-masters, where they's ben, or what they's ben a

doin', or how they got their money. Ask me no

questions, and I'll tell ye no lies, is 'bout the best

philosophy for them. Wal, it didn't do no good to

ask Cap'n Brown questions too close, 'cause you

didn't git no satisfaction. Nobody rightly knew

'bout who his folks was, or where they come from;

and, ef a body asked him, he used to say that the

very fust he know'd 'bout himself he was a young

man walkin' the streets in London.

“But, yer see, boys, he hed money, and that is

about all folks wanter know when a man comes to

settle down. And he bought that 'are place, and

built that 'are house. He built it all sea-cap'n

fashion, so's to feel as much at home as he could.

The parlor was like a ship's cabin. The table and

chairs was fastened down to the floor, and the closets

was made with holes to set the casters and the

decanters and bottles in, jest's they be at sea;

and there was stanchions to hold on by; and they

say that blowy nights the cap'n used to fire up

pretty well with his grog, till he hed about all he

could carry, and then he'd set and hold on, and hear

the wind blow, and kind o' feel out to sea right

there to hum. There wasn't no Mis' Cap'n Brown,

and there didn't seem likely to be none. And

whether there ever hed been one, nobody know'd.

He hed an old black Guinea nigger-woman, named

Quassia, that did his work. She was shaped pretty

much like one o' these 'ere great crookneck-squashes.

She wa'n't no gret beauty, I can tell you; and she

used to wear a gret red turban and a yaller short

gown and red petticoat, and a gret string o' gold

her ears, made right in the middle o' Africa among

the heathen there. For all she was black, she

thought a heap o' herself, and was consid'able sort

o' predominative over the cap'n. Lordy massy!

boys, it's allus so. Get a man and a woman together,

— any sort o' woman you're a mind to, don't care

who 'tis, — and one way or another she gets the rule

over him, and he jest has to train to her fife. Some

does it one way, and some does it another; some does

it by jawin', and some does it by kissin', and some

does it by faculty and contrivance; but one way or

another they allers does it. Old Cap'n Brown was a

good stout, stocky kind o' John Bull sort o' fellow,

and a good judge o' sperits, and allers kep' the best

in them are cupboards o' his'n; but, fust and last,

things in his house went pretty much as old Quassia

said.

“Folks got to kind o' respectin' Quassia. She

come to meetin' Sunday regular, and sot all fixed up

in red and yaller and green, with glass beads and

what not, lookin' for all the world like one o' them

ugly Indian idols; but she was well-behaved as any

bread and biscuits couldn't be beat, and no couldn't

her pies, and there wa'n't no such pound-cake as she

made nowhere. Wal, this 'ere story I'm a goin' to

tell you was told me by Cinthy Pendleton. There

ain't a more respectable gal, old or young, than

Cinthy nowheres. She lives over to Sherburne now,

and I hear tell she's sot up a manty-makin' business;

but then she used to do tailorin' in Oldtown. She

was a member o' the church, and a good Christian as

ever was. Wal, ye see, Quassia she got Cinthy to

come up and spend a week to the Cap'n Brown

house, a doin' tailorin' and a fixin' over his close:

'twas along toward the fust o' March. Cinthy she

sot by the fire in the front parlor with her goose and

her press-board and her work: for there wa'n't no

company callin', and the snow was drifted four feet

deep right across the front door; so there wa'n't

much danger o' any body comin' in. And the cap'n

he was a perlite man to wimmen; and Cinthy she

liked it jest as well not to have company, 'cause the

cap'n he'd make himself entertainin' tellin' on her

sea-stories, and all about his adventures among the

sorts o' heathen people he'd been among.

“Wal, that 'are week there come on the master

snow-storm. Of all the snow-storms that hed ben,

that 'are was the beater; and I tell you the wind blew

as if 'twas the last chance it was ever goin' to hev.

Wal, it's kind o' scary like to be shet up in a lone

house with all natur' a kind o' breakin' out, and goin'

on so, and the snow a comin' down so thick ye can't

see 'cross the street, and the wind a pipin' and a

squeelin' and a rumblin' and a tumblin' fust down this

chimney and then down that. I tell you, it sort o'

sets a feller thinkin' o' the three great things, —

death, judgment, and etarnaty; and I don't care who

the folks is, now how good they be, there's times

when they must be feelin' putty consid'able solemn.

“Wal, Cinthy she said she kind o' felt so along,

and she hed a sort o' queer feelin' come over her as

if there was somebody or somethin' round the house

more'n appeared. She said she sort o' felt it in the

air; but it seemed to her silly, and she tried to get

over it. But two or three times, she said, when it

got to be dusk, she felt somebody go by her up the

and in the storm, come five o'clock, it was so

dark that all you could see was jest a gleam o' somethin',

and two or three times when she started to go

up stairs she see a soft white suthin' that seemed

goin' up before her, and she stopped with her heart a

beatin' like a trip-hammer, and she sort o' saw it go

up and along the entry to the cap'n's door, and then

it seemed to go right through, 'cause the door didn't

open.

“Wal, Cinthy says she to old Quassia, says she,

`Is there anybody lives in this house but us?'

“`Anybody lives here?' says Quassia: `what you

mean?' says she.

“Says Cinthy, `I thought somebody went past me

on the stairs last night and to-night.'

“Lordy massy! how old Quassia did screech and

laugh. `Good Lord!' says she, `how foolish white

folks is! Somebody went past you? Was't the

capt'in?'

“`No, it wa'n't the cap'n,' says she: `it was

somethin' soft and white, and moved very still; it

was like somethin' in the air,' says she.

Then Quassia she haw-hawed louder. Says she,

`It's hy-sterikes, Miss Cinthy; that's all it is.'

“Wal, Cinthy she was kind o' 'shamed, but for all

that she couldn't help herself. Sometimes evenin's

she'd be a settin' with the cap'n, and she'd think she'd

hear somebody a movin' in his room overhead; and

she knowed it wa'n't Quassia, 'cause Quassia was

ironin' in the kitchen. She took pains once or twice

to find out that 'are.

“Wal, ye see, the cap'n's room was the gret front

upper chamber over the parlor, and then right oppisite

to it was the gret spare chamber where Cinthy

slept. It was jest as grand as could be, with a gret

four-post mahogany bedstead and damask curtains

brought over from England; but it was cold enough

to freeze a white bear solid, — the way spare chambers

allers is. Then there was the entry between,

run straight through the house: one side was old

Quassia's room, and the other was a sort o' store-room,

where the old cap'n kep' all sorts o' traps.

“Wal, Cinthy she kep' a hevin' things happen and

a seein' things, till she didn't railly know what was

in it. Once when she come into the parlor jest at

out o' the door that went towards the side

entry. She said it was so dusk, that all she could see

was jest this white figure, and it jest went out still as

a cat as she come in.

“Wal, Cinthy didn't like to speak to the cap'n

about it. She was a close woman, putty prudent,

Cinthy was.

“But one night, 'bout the middle o' the week, this

'ere thing kind o' come to a crisis.

“Cinthy said she'd ben up putty late a sewin' and

a finishin' off down in the parlor; and the cap'n he

sot up with her, and was consid'able cheerful and

entertainin', tellin' her all about things over in the

Bermudys, and off to Chiny and Japan, and round

the world ginerally. The storm that hed been a

blowin' all the week was about as furious as ever;

and the cap'n he stirred up a mess o' flip, and hed it

for her hot to go to bed on. He was a good-natured

critter, and allers had feelin's for lone women; and I

s'pose he knew 'twas sort o' desolate for Cinthy.

“Wal, takin' the flip so right the last thing afore

goin' to bed, she went right off to sleep as sound as

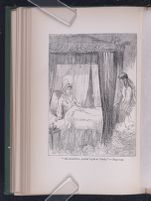

“She stood there, lookin' right at Cinthy.”—Page 149.

[Description: 703EAF. Illustration page. Image of a woman sitting up in bed. Another woman stands at the foot of the bed. The bed is surrounded by smoke, which is higher near the standing woman so that she appears to be rising out of it.]

when she said somethin' waked her broad awake in a

minute. Her eyes flew wide open like a spring, and

the storm hed gone down and the moon come out;

and there, standin' right in the moonlight by her bed,

was a woman jest as white as a sheet, with black hair

hangin' down to her waist, and the brightest, mourn

fullest black eyes you ever see. She stood there

lookin' right at Cinthy; and Cinthy thinks that was

what waked her up; 'cause, you know, ef anybody

stands and looks steady at folks asleep it's apt to

wake 'em.

“Any way, Cinthy said she felt jest as ef she was

turnin' to stone. She couldn't move nor speak.

She lay a minute, and then she shut her eyes, and

begun to say her prayers; and a minute after she

opened 'em, and it was gone.

“Cinthy was a sensible gal, and one that allers

hed her thoughts about her; and she jest got up and

put a shawl round her shoulders, and went first and

looked at the doors, and they was both on 'em locked

jest as she left 'em when she went to bed. Then

she looked under the bed and in the closet, and

felt her way, and there wa'n't nothin' there.

“Wal, next mornin' Cinthy got up and went

home, and she kep' it to herself a good while.

Finally, one day when she was workin' to our house

she told Hepsy about it, and Hepsy she told me.”

“Well, Sam,” we said, after a pause, in which we

heard only the rustle of leaves and the ticking of

branches against each other, “what do you suppose

it was?”

“Wal, there 'tis: you know jest as much about

it as I do. Hepsy told Cinthy it might 'a' ben a

dream; so it might, but Cinthy she was sure it

wa'n't a dream, 'cause she remembers plain hearin'

the old clock on the stairs strike four while she had

her eyes open lookin' at the woman; and then she

only shet 'em a minute, jest to say `Now I lay me,'

and opened 'em and she was gone.

“Wal, Cinthy told Hepsy, and Hepsy she kep' it

putty close. She didn't tell it to nobody except

Aunt Sally Dickerson and the Widder Bije Smith

and your Grandma Badger and the minister's wife;

and they every one o' 'em 'greed it ought to be kep'

somehow or other it seemed to 'a' got all over Oldtown.

I heard on 't to the store and up to the tavern;

and Jake Marshall he says to me one day,

`What's this 'ere about the cap'n's house?' And

the Widder Loker she says to me, `There's ben a

ghost seen in the cap'n's house;' and I heard on 't

clear over to Needham and Sherburne.

“Some o' the women they drew themselves up

putty stiff and proper. Your Aunt Lois was one on

'em.

“`Ghost,' says she; `don't tell me! Perhaps it

would be best ef 'twas a ghost,' says she. She

didn't think there ought to be no sich doin's in nobody's

house; and your grandma she shet her up,

and told her she didn't oughter talk so.”

“Talk how?” said I, interrupting Sam with wonder.

“What did Aunt Lois mean?”

“Why, you see,” said Sam mysteriously, “there

allers is folks in every town that's jest like the

Sadducees in old times: they won't believe in angel

nor sperit, no way you can fix it; and ef things is

seen and done in a house, why, they say, it's 'cause

or trick about it.

“So the story got round that there was a woman

kep' private in Cap'n Brown's house, and that he

brought her from furrin parts; and it growed and

growed, till there was all sorts o' ways o' tellin on 't.

“Some said they'd seen her a settin' at an open

winder. Some said that moonlight nights they'd

seen her a walkin' out in the back garden kind o' in

and out 'mong the bean-poles and squash-vines.

“You see, it come on spring and summer; and the

winders o' the Cap'n Brown house stood open, and

folks was all a watchin' on 'em day and night. Aunt

Sally Dickerson told the minister's wife that she'd

seen in plain daylight a woman a settin' at the

chamber winder atween four and five o'clock in the

mornin', — jist a settin' a lookin' out and a doin'

nothin', like anybody else. She was very white and

pale, and had black eyes.

“Some said that it was a nun the cap'n had

brought away from a Roman Catholic convent in

Spain, and some said he'd got her out o' the Inquisition.

“Aunt Sally said she thought the minister ought

to call and inquire why she didn't come to meetin',

and who she was, and all about her: 'cause, you see,

she said it might be all right enough ef folks only

know'd jest how things was; but ef they didn't,

why, folks will talk.”

“Well, did the minister do it?”

“What, Parson Lothrop? Wal, no, he didn't.

He made a call on the cap'n in a regular way, and

asked arter his health and all his family. But the

cap'n he seemed jest as jolly and chipper as a spring

robin, and he gin the minister some o' his old

Jamaiky; and the minister he come away and said

he didn't see nothin'; and no he didn't. Folks

never does see nothin' when they aint' lookin' where

'tis. Fact is, Parson Lothrop wa'n't fond o' interferin';

he was a master hand to slick things over.

Your grandma she used to mourn about it, 'cause

she said he never gin no p'int to the doctrines; but

'twas all of a piece, he kind o' took every thing the

smooth way.

“But your grandma she believed in the ghost,

and so did Lady Lothrop. I was up to her house

your wife told me a strange story about the Cap'n

Brown house.'

“`Yes, ma'am, she did,' says I.

“`Well, what do you think of it?' says she.

“`Wal, sometimes I think, and then agin I don't

know,' says I. `There's Cinthy she's a member o'

the church and a good pious gal,' says I.

“`Yes, Sam,' says Lady Lothrop, says she; `and

Sam,' says she, `it is jest like something that happened

once to my grandmother when she was livin'

in the old Province House in Bostin.' Says she,

`These 'ere things is the mysteries of Providence,

and it's jest as well not to have 'em too much talked

about.'

“`Jest so,' says I, — `jest so. That 'are's what

every woman I've talked with says; and I guess, fust

and last, I've talked with twenty, — good, safe

church-members, — and they's every one o' opinion

that this 'ere oughtn't to be talked about. Why,

over to the deakin's t'other night we went it all

over as much as two or three hours, and we concluded

that the best way was to keep quite still

and Sherburne. I've been all round a hushin'

this 'ere up, and I hain't found but a few people that

hedn't the particulars one way or another.' This 'ere

was what I says to Lady Lothrop. The fact was, I

never did see no report spread so, nor make sich sort

o' sarchin's o' heart, as this 'ere. It railly did beat

all; 'cause, ef 'twas a ghost, why there was the p'int

proved, ye see. Cinthy's a church-member, and she

see it, and got right up and sarched the room: but

then agin, ef 'twas a woman, why that 'are was kind

o' awful; it give cause, ye see, for thinkin' all sorts

o' things. There was Cap'n Brown, to be sure, he

wa'n't a church-member; but yet he was as honest

and regular a man as any goin', as fur as any on us

could see. To be sure, nobody know'd where he

come from, but that wa'n't no reason agin' him: this

'ere might a ben a crazy sister, or some poor critter

that he took out o' the best o' motives; and the

Scriptur' says, `Charity hopeth all things.' But

then, ye see, folks will talk, — that 'are's the pester

o' all these things, — and they did some on 'em

talk consid'able strong about the cap'n; but somehow

o' facin' on him down, and sayin' square out, `Cap'n

Brown, have you got a woman in your house, or

hain't you? or is it a ghost, or what is it?' Folks

somehow neverdoes come to that. Ye see, there was

the cap'n so respectable, a settin' up every Sunday

there in his pew, with his ruffles round his hands and

his red broadcloth cloak and his cocked hat. Why,

folks' hearts sort o' failed 'em when it come to sayin'

any thing right to him. They thought and kind o'

whispered round that the minister or the deakins

oughter do it: but Lordy massy! ministers, I s'pose,

has feelin's like the rest on us; they don't want to

eat all the hard cheeses that nobody else won't eat.

Anyhow, there wasn't nothin' said direct to the

cap'n; and jest for want o' that all the folks in Oldtown

kep' a bilin' and a bilin' like a kettle o' soap,

till it seemed all the time as if they'd bile over.

“Some o' the wimmen tried to get somethin' out

o' Quassy. Lordy massy! you might as well 'a' tried

to get it out an old tom-turkey, that'll strut and

gobble and quitter, and drag his wings on the ground,

and fly at you, but won't say nothin'. Quassy she

that they was a makin' fools o' themselves, and that

the cap'n's matters wa'n't none o' their bisness;

and that was true enough. As to goin' into Quassia's

room, or into any o' the store-rooms or closets

she kep' the keys of, you might as well hev gone

into a lion's den. She kep' all her places locked up

tight; and there was no gettin' at nothin' in the

Cap'n Brown house, else I believe some o' the wimmen

would 'a' sent a sarch-warrant.”

“Well,” said I, “what came of it? Didn't anybody

ever find out?”

“Wal,” said Sam, “it come to an end sort o', and

didn't come to an end. It was jest this 'ere way.

You see, along in October, jest in the cider-makin'

time, Abel Flint he was took down with dysentery

and died. You 'member the Flint house: it stood

on a little rise o' ground jest lookin' over towards

the Brown house. Wal, there was Aunt Sally

Dickerson and the Widder Bije Smith, they set up

with the corpse. He was laid out in the back chamber,

you see, over the milk-room and kitchen; but

there was cold victuals and sich in the front chamber,

told me that between three and four o'clock she

heard wheels a rumblin', and she went to the winder,

and it was clear starlight; and she see a coach come

up to the Cap'n Brown house; and she see the cap'n

come out bringin' a woman all wrapped in a cloak,

and old Quassy came arter with her arms full o' bundles;

and he put her into the kerridge, and shet her in,

and it driv off; and she see old Quassy stand lookin'

over the fence arter it. She tried to wake up the

widder, but 'twas towards mornin', and the widder

allers was a hard sleeper; so there wa'n't no witness

but her.”

“Well, then, it wasn't a ghost,” said I, “after all,

and it was a woman.”

“Wal, there 'tis, you see. Folks don't know that

'are yit, 'cause there it's jest as broad as 'tis long.

Now, look at it. There's Cinthy, she's a good, pious

gal: she locks her chamber-doors, both on 'em, and

goes to bed, and wakes up in the night, and there's a

woman there. She jest shets her eyes, and the woman's

gone. She gits up and looks, and both doors is

locked jest as she left 'em. That 'ere woman wa'n't

blood as we knows on; but then they say Cinthy

might hev dreamed it!

“Wal, now, look at it t'other way. There's Aunt

Sally Dickerson; she's a good woman and a church-member:

wal, she sees a woman in a cloak with all

her bundles brought out o' Cap'n Brown's house, and

put into a kerridge, and driv off, atween three and

four o'clock in the mornin'. Wal, that 'ere shows

there must 'a' ben a real live woman kep' there privately,

and so what Cinthy saw wasn't a ghost.

“Wal, now, Cinthy says Aunt Sally might 'a'

dreamed it, — that she got her head so full o' stories

about the Cap'n Brown house, and watched it till she

got asleep, and hed this 'ere dream; and, as there

didn't nobody else see it, it might 'a' ben, you know.

Aunt Sally's clear she didn't dream, and then agin

Cinthy's clear she didn't dream; but which on 'em

was awake, or which on 'em was asleep, is what ain't

settled in Oldtown yet.”

| Sam Lawson's Oldtown fireside stories | ||