Artemus Ward in London and other papers |

| 1. |

| 2. | PART II.

ESSAYS AND SKETCHES.

From the “Cleveland Plaindealer.” |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. |

| 30. |

| 31. |

| 32. |

| 33. |

| 34. |

| 35. |

| Artemus Ward in London | ||

2. PART II.

ESSAYS AND SKETCHES.

From the “Cleveland Plaindealer.”

1. ESSAYS AND SKETCHES

I.

ABOUT EDITORS.

We hear a great deal, and something

too much about the poverty of editors. It

is common for editors to parade their poverty

and joke about it in their papers. We

see these witticisms almost every day of

our lives. Sometimes the editor does the

“vater vorks business,” as Mr. Samuel

Weller called weeping, and makes pathetic

appeals to his subscribers. Sometimes he

is in earnest when he makes these appeals,

but why “on airth” does he stick to

a business that will not support him decently?

We read of patriotic and lofty-minded

time, money, and perhaps life for the good

of humanity, the Union and that sort of

thing, but we don't see them very often. We

must say that we could count up all the

lofty patriots in this line that we have ever

seen, during our brief but checquered and

romantic career, in less than half a day.

A man who clings to a wretchedly paying

business, when he can make himself and

others near and dear to him fatter and happier

by doing something else, is about as

near an ass as possible and not hanker

after green grass and corn in the ear. The

truth is, editors as a class are very well fed,

groomed and harnessed. They have some

pains that other folk do not have, and

they also have some privileges which the

community in general can't possess. While

we would not advise the young reader to

“go for an editor,” we assure him he can

do much worse. He mustn't spoil a flourishing

blacksmith or popular victualer in

making an indifferent editor of himself,

however. He must be endowed with some

fancy and imagination to enchain the public

other man with an odd name, who thought

Shakspeare lacked the requisite fancy and

imagination for a successful editor.

To those persons who can't live by

printing papers we would say, in the language

of the profligate boarder when dunned

for his bill, being told at the same time

by the keeper of the house that he couldn't

board people for nothing, “sell out to

somebody who can.” In other words, fly

from a business which don't remunerate.

But as we intimated before, there is much

gammon in the popular editorial cry of

poverty.

Just now we see a touching paragraph

floating through the papers to the effect

that editors don't live out half their years

—that, poor souls! they wear themselves

out for the benefit of a cold and unappreciating

world. We don't believe it. Gentle

reader, don't swallow it. It is a footlight

trick to work on your feelings. For ourselves,

let us say, that unless we slip up

considerably on our calculations, it will be

a long time before our fellow-citizens will

to our memory a towering monument of

Parian marble on the Public Square.

Items.—They are very “scarce.” Readers

may complain at the lack of local news

in our papers, but where can we get it?

We are in about as bad a fix as the French

leader of the orchestra in a theatre “Out

West” was. He was flourishing his baton

in the most frantic manner—the fiddles

were squeaking—the brass instruments

were braying—the cymbals were clashing,

and the orchestra was making all the noise

it possibly could. But a man in the pit

wasn't satisfied. “Louder! louder! louder!”

he yelled. The French leader dropped his

baton in despair, wiped the perspiration

from his brow, told the orchestra to cease

playing, and violently spoke as follows:—

“The gen'lman may cry loud-AR as much

as he please, but vere we get de wind, by

gar?” A few hours of active study will

show the reader that the comparison is a

good one.

2. II.

EDITING.

Before you go for an Editor, young man,

pause and take a big think! Do not rush

into the Editorial harness rashly. Look

around and see if there is not an omnibus

to drive—some soil somewhere to be tilled

—a clerkship on some meat cart to be filled—anything

that is reputable and healthy,

rather than going for an Editor, which is

hard business at best.

We are not a horse, and consequently

have never been called upon to furnish the

motive power for a threshing machine; but

we fancy that the life of the Editor, who is

forced to write, write, write, whether he feels

right or not, is much like that of the steed

in question. If the yeas and neighs could

be obtained we believe the intelligent horse

would decide that the threshing machine is

preferable to the sanctum Editorial.

The Editor's work is never done. He is

drained incessantly, and no wonder that he

dries up prematurely. Other people can

attend banquets, weddings, etc.; visit halls

of dazzling light, get inebriated, break

windows, lick a man occasionally, and enjoy

themselves in a variety of ways; but the

Editor cannot. He must stick tenaciously

to his quill. The press, like a sick baby,

mustn't be left alone for a minute. If the

press is left to run itself even for a day,

some absurd person indignantly orders the

carrier-boy to stop bringing “that infernal

paper. There's nothing in it. I won't

have it in the house!”

The elegant Mantalini, reduced to man-gleturning,

described his life as “a dem'd

horrid grind.” The life of the Editor is

all of that.

But there is a good time coming, we feel

confident, for the Editor. A time when

he will be appreciated. When he will

have a front seat. When he will have pie

every day, and wear store clothes continually.

When the harsh cry of “stop my

paper” will no more grate upon his ears.

sanguine as we are of the coming of this

jolly time, we advise the aspirant for Editorial

honors to pause ere he takes up the

quill as a means of obtaining his bread and

butter. Do not, at least, do so until you

have been jilted several dozen times by

a like number of girls; until you have been

knocked down stairs and soused in a horsepond;

until all the “gushing” feelings

within you have been thoroughly subdued;

until, in short, your hide is of rhinoceros

thickness. Then, O aspirants for the

bubble reputation at the press's mouth,

throw yourselves among the inkpots, dust,

and cobwebs of the printing office, if you

will.

* * * Good my lord, will you see the

Editors well bestowed? Do you hear, let

them be well used, for they are the abstract

and brief chronicles of the time. After

your death you had better have a bad epitaph

than their ill report while you live.

3. III.

MORALITY AND GENIUS.

We see it gravely stated in a popular

Metropolitan journal that “true genius

goes hand in hand, necessarily, with morality.”

The statement is not a startlingly

novel one. It has been made, probably,

about sixty thousand times before. But it

is untrue and foolish. We wish genius

and morality were affectionate companions,

but it is a fact that they are often bitter

enemies. They don't necessarily coalesce

any more than oil and water do. Innumerable

instances may be readily produced in

support of this proposition. Nobody doubts

that Sheridan had genius, yet he was a sad

dog. Mr. Byron, the author of Childe

Harold “and other poems,” was a man of

genius, we think, yet Mr. Byron was a fearfully

fast man. Edgar A. Poe wrote magnificent

was in private life hardly the man for small

and select tea parties. We fancy Sir Richard

Steele was a man of genius, but he got

disreputably drunk, and didn't pay his debts.

Swift had genius—an immense lot of it—

yet Swift was a cold-blooded, pitiless, bad

man. The catalogue might be spun out to

any length, but it were useless to do it. We

don't mean to intimate that men of genius

must necessarily be sots and spendthrifts—

we merely speak of the fact that very many

of them have been both, and in some instances

much worse than both. Still we

can't well see (though some think they can)

how the pleasure and instruction people

derive from reading the productions of

these great lights is diminished because

their morals were “lavishly loose.” They

might have written better had their private

lives been purer, but of this nobody can

determine, for the pretty good reason that

nobody knows.

So with actors. We have seen people

stay away from the theater because Mrs.

Grundy said the star of the evening invariably

extreme inebriety. If the star is afflicted

with a weakness of this kind, we may regret

it. We may pity or censure the star. But

we must still acknowledge the star's genius,

and applaud it. Hence we conclude that

the chronic weaknesses of actors no more

affect the question of the propriety of patronizing

theatrical representations, than the

profligacy of journeymen shoemakers affects

the question of the propriety of wearing

boots. All of which is respectfully submitted.

4. IV.

POPULARITY.

What a queer thing is popularity. Bill

Pug Nose of the “Plug-Uglies” acquires a

world-wide reputation by smashing up the

“champion of light weights,” sets up a Saloon

upon it, and realizes the first month;

while our Missionary, who collected two

hundred blankets last August, and at that

time saved a like number of little negroes

in the West Indies from freezing, has received

nothing but the yellow fever. The

Hon. Oracular M. Matterson becomes able

to withstand any quantity of late nights and

bad brandy, is elected to Congress, and lobbies

through contracts by which he realizes

some $50,000, while private individuals

lose $100,000 by the Atlantic Cable. Contracts

are popular—the cable isn't. Fiddlers,

Prima-Donnas, Horse Operas, learned

the country, reaping “golden opinions,

while editors, inventors, professors and

humanitarians generally, are starving in

garrets. Revivals of religion, fashions,

summer resorts, and pleasure trips, are exceedingly

popular, while trade, commerce,

chloride of lime, and all the concomitants

necessary to render the inner life of denizens

of cities tolerable, are decidedly NON

EST. Even water, which was so popular

and populous a few weeks agone, comes to

us in such stinted sprinklings that it has

become popular to supply it only from

hydrants in sufficient quantities to raise

one hundred disgusting smells in a distance

of two blocks. Monsieur Revierre, with

nothing but a small name and a large

quantity of hair, makes himself exceedingly

popular with hotel-keepers and a numerous

progeny of female Flaunts and Blounts,

while Felix Smooth and Mr. Chink, who

persistently set forth their personal and

more substantial marital charms through

the columns of the New York Herald,

have only received one interview each—

other from the keeper of an unmentionable

house. Popularity is a queer thing, very.

If you don't believe us, try it!

Dull.—It is a scandalous fact that this

city is desperately and fearfully barren of

incident. No “dem'd, moist unpleasant

bodies” are fished up out of the river; no ambitious

young female runs off with her “feller;”

no stabbings, gougings, or fisticuffs

occur; no eminent merchant suspends; no

banker or railroad man defaults, and not

even a dog-fight disturbs the rigid and corpse-like

quiet of the city. We want a murder.

We insist upon having a murder. A manslaughter

won't do. It must be murder,

premeditated, foul, and unnatural. It must

be a luscious murder, abounding in soulharrowing

incidents. Some “man in human

shape” must chop the heads of his entire

family off with a meat-axe, or insert a

butcher-knife ingeniously under their fifth

ribs. Let murder be done. Bring on your

murderers. We want to be Rochestered!

5. V.

A LITTLE DIFFICULTY IN THE WAY.

An enterprising traveling agent for a

well-known Cleveland Tomb Stone Manufactory

lately made a business visit to a

small town in an adjoining county. Hearing,

in the village, that a man in a remote

part of the township had lost his wife, he

thought he would go and see him and offer

him consolation and a gravestone, on his

usual reasonable terms. He started. The

road was a frightful one, but the agent persevered,

and finally arrived at the bereaved

man's house. Bereaved man's hired girl

told the agent that the bereaved man was

splitting fence rails “over in the pastur,

about two milds.” The indefatigable agent

hitched his horse and started for the “pastur.”

After falling into all manner of

mudholes, scratching himself with briers,

and tumbling over decayed logs, the agent

subdued voice he asked the man if he had

lost his wife. The man said he had. The

agent was very sorry to hear of it, and sympathized

with the man very deeply in his

great afflication; but death, he said, was an

insatiate archer, and shot down all, both of

high and low degree. Informed the man

that “what was his loss was her gain,” and

would be glad to sell him a gravestone

to mark the spot where the beloved one

slept—marble or common stone, as he

chose, at prices defying competition. The

bereaved man said there was “a little difficulty

in the way.” “Haven't you lost

your wife?” inquired the agent. “Why

yes, I have,” said the man, “but no grave

stun ain't necesary: you see the cussed

critter ain't dead. She's scooted with

another man!” The agent retired.

6. VI.

OTHELLO.

Everybody knows that this is one of

Mr. W. Shakespeare's best and most attractive

plays. The public is more familiar

with Othello than any other of “the great

Bard's” efforts. It is the most quoted from

by writers and orators, Hamlet perhaps

excepted, and provincial theaters seem to

take more delight in doing it than almost

any other play extant, legitimate or otherwise.

The scene is laid in Venice. Othello,

a warm-hearted, impetuous and rather

verdant Moorish gentleman, considerably

in the military line, falls in love and marries

Desdemona, daughter of the Hon. Mr.

Brabantio, who represents one of the

“back districts” in the Venetian Senate.

The Senator is quite vexed at this—rends

his linen and swears considerably—but

finally dries up, requesting the Moor to remember

Pa, and bidding him to look out that she

don't likewise come it over him, “or words

to that effect.” Mr. and Mrs. Othello get

along very pleasantly for awhile. She is

sweet-tempered and affectionate—a nice,

sensible woman, not at all inclined to pantaloons,

he-female conventions, pickled-beets

and other “strong-minded” arrangements.

He is a likely man and “a good

provider.” But a man named Iago, who

we believe wants to get Mr. O. out of

his snug government berth that he may

get into it, systematically and effectually

ruins the Othello household. Had there

been a Lecompton Constitution up, Iago

would have been an able and eloquent advocate

of it, and would thus have got

Othello's position, for the Moor would have

utterly repudiated that pet scheme of the

Devil and several other gentlemen, whose

names we omit out of regard for the feelings

of their parents. Lecompton wasn't

a “test,” however, and Iago took another

course to oust Othello. He fell in with a

brainless young man named Roderigo and

played foul.) We suppose he did

this to procure funds to help him carry out

his vile scheme. Michael Cassio, whose

first name would imply that he was of the

Irish persuasion, was the unfortunate individual

selected by Mr. I. as his principal

tool. This Cassio was a young officer of

considerable promise and high moral worth.

He yet unhappily had a weakness for drink,

and though this weakness Mr. I. determined

to “fetch him.” He accordingly

proposed a drinking bout with Michael.

Michael drank faithfully every time, but

Iago adroitly threw his whiskey on the

floor. While Cassio is pouring the liquor

down his throat Iago sings a popular bacchanalian

song, the first verse of which is

as follows:

And let me the canakin clink:

A soldier's a man,

A life's but a span,

Why then let a soldier drink.”

The “canakin is clinked” until Michael

about seven inches of whisky in him. He

says he is sober, and thinks he can walk a

crack with distinguished success. He then

grows religious and “hopes to be saved.”

He then wants to fight, and allows he can

lick a yard full of the Venetian fancy. He

falls in with Roderigo and proceeds to

smash him. Montano undertakes to stop

Cassio, when that intoxicated person stabs

him. Iago pretends to be very sorry to

see Michael conduct himself in this improper

manner, and undertakes to smooth

the thing over to Othello, who rushes in

with a drawn sword and wants to know

what's up. Iago cunningly gives his villanous

explanation, and Othello tells

Michael that he loves him but he can't

train in his regiment any more. Desdemona,

the gentle and good, sympathizes

with Cassio and intercedes for him with

the Moor. Iago gives the Moor to understand

that she does this because she

likes Michael better than she does his own

dark-faced self, and intimates that their

relations (Desdemona's and Michael's) are

Moor believes the villain's yarn, and commences

making himself unhappy and disagreeable

generally. Iago tells Othello

what he heard Cassio say about “sweet

Desdemona” in his dreams, but of course

the story was a creation of Iago's fruitful

brain—in short, a lie. The poor Moor

swallows it, though, and storms terribly.

He grabs Iago by the throat and tells him

to give him the ocular proof. Iago becomes

virtuously indignant and is sorry he mentioned

the subject to the Moor. The Moor

relents and believes Iago. He then tortures

Desdemona with his foul suspicions,

and finally smothers her with a pillow

while she is in bed. Mrs. Iago, who is a

woman of spirit, comes in on the Moor

just as he has finished the murder. She

gives it to him right smartly, and shows

him he has been terribly deceived. Mr.

Iago enters. Mrs. Iago pitches into him

and he stabs her. Othello gives him

a piece of his mind and subsequently a

piece of his sword. Iago, with a sardonic

smile, says he bleeds but isn't hurt much.

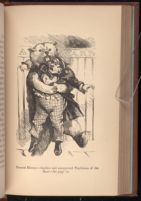

Natural History—Sudden and unexpected Playfulness of the Bear—See page 70.

[Description: 484EAF. Image of Ward being grabbed from behind by a giant bear. Ward is looking backwards toward the bear, which is standing tall and baring his teeth.]

another sardonic smile, points to the death-couch

of poor Desdemona. He then goes

off. Othello tells the assembled dignitaries

that he has done the State some service

and they know it; asks them to speak of

him as he is, and do as fair a thing as they

can under the circumstances; calls himself

a circumcised dog, and kills himself, which

is the most sensible thing he can do.

7. VII.

SCENES OUTSIDE THE FAIR GROUND.

There is some fun outside the Fair

Ground. Any number of mountebanks

have pitched their tents there, and are

exhibiting all sorts of monstrosities to large

and enthusiastic audiences. There are

some eloquent men among the showmen.

Some of them are Demosthenic. We

looked around among them during the

last day we honored the Fair with our

brilliant presence, and were rather pleased

at some things we heard and witnessed.

The man with the fat woman and the

little woman and the little man was there.

“ `Ere's a show now,” said he, “worth

seeing. `Ere's a entertainment that improves

the morals. P. T. Barnum—you've

all hearn o' him. What did he say to

me? Sez he to me, sez P. T. Barnum,

`Sir, you have the damdist best show

small sum of fifteen cents!”

The man with the blue hog was there.

Says he, “GentleMEN, this beast can't turn

round in a crockery grate ten feet square

and is of a bright indigo blue. Over five

hundred persons have seen this wonderful

BEING this mornin', and they said as they

come out, `What can these `ere things be?

Is it alive? Doth it breathe and have

a being? Ah yes, they say, it is true,

and we have saw a entertainment as we

never saw afore. `Tis nature's [only

fifteen cents—`ere's your change, Sir] own

sublime handiworks'—and walk right in.”

The man with the wild mare was there.

“Now, then, my friends, is your time to

see the gerratist queeriosity in the livin'

world—a wild mare without no hair—captered

on the roarin' wild prahayries of

the far distant West by sixteen Injuns.

Don't fail to see this gerrate exhibition.

Only fifteen cents. Don't go hum without

seein' the State Fair, an' you won't see the

State Fair without you see my show. Gerratist

exhibition in the known world, an' all

gentlemen connected with the press here

walked up and asked the showman, in

a still small voice, if he extended the usual

courtesies to editors. He said he did, and

requested them to go in. While they

were in some sly dog told him their names.

When they came out the showman pretended

to talk with them, though he didn't

say a word. They were evidently in a

hurry. “There, gentleMEN, what do you

think them gentlemen say? They air

editors—editors, gentleMEN—Mr.—of

the Cleveland—, and Mr.—of the

Detroit—, and they say it is the gerratist

show they ever seed in their born

days!” [Nothing but the tip ends of the

editors' coat-tails could be seen when the

showman concluded this speech.]

A smart-looking chap was doing a brisk

business with a gambling contrivance. Seeing

two policemen approach, he rapidly

and ingeniously covered the dice up, mounted

his table, and shouted: “ `Ere's the

only great show on the grounds! The

highly trained and performing Mud Turtle

in a well-fortified hencoop, after a

desperate struggle, in the lowlands of

the Wabash!!” The facetious wretch escaped.

A grave, ministerial-looking and elderly

man in a white choker had a gift-enterprise

concern. “My friends,” he solemnly said,

“you will observe that this jewelry is elegant

indeed, but I can afford to give it

away, as I have a twin brother seven years

older than I am, in New York City, who

steals it a great deal faster than I can give

it away. No blanks, my friends—all prizes

—and only fifty cents a chance. I don't

make anything myself, my friends—all I get

goes to aid a sick woman—my aunt in the

country, gentlemen—and besides I like to

see folks enjoy themselves!” The old

scamp said all this with a perfectly grave

countenance.

The man with the “wonderful calf with

five legs and a huming head,” and “the philosophical

lung-tester,” were there. Then

there was the Flying Circus and any number

of other igenious contrivances to relieve

rural districts of their spare change.

A young man was bitterly bewailing the

loss of his watch, which had been cut from

his pocket by some thief. “You ain't

smart,” said a middle-aged individual in a

dingy Kossuth hat with a feather in it, and

who had a very you-can't-fool-me look.

“I've been to the State Fair before, I want

yer to understan', and know my bizniss

aboard a propeller. Here's MY money,” he

exultingly cried, slapping his pantaloons'

pocket.” About half an hour after this we

saw this smart individual rushing frantically

around after a policeman. Somebody

had adroitly relieved him of HIS money. In

his search for a policeman he encountered

the young man who wasn't smart. “Haw,

haw, haw,” violently laughed the latter, “by

G—, I thought you was smart—I thought

you'd been to the State Fair before.” The

smart man looked sad for a moment, but a

knowing smile soon crossed his face, and

drawing the young man who wasn't smart

confidentially towards him, said: “There

wasn't only fifty cents in coppers in my

can't fool me—I've been to the State

Fair before!!”

He Declined “Biling.”—The students

of the Conneaut Academy gave a theatrical

entertainment a few winters ago. They

“executed” Julius Cæsar. Everything went

off satisfactorily until Cæsar was killed in

the market-place. The stage accommodations

were limited, and Cæsar fell nearly

under the stove in which there was a roaring

fire. And when Brutus said—

Fly not; stand still—ambition's debt is paid!”

feet and nervously examine his scorched

garments. “Lay down, you fool,” shouted

Brutus, wildly, “do you want to break up

the whole thing?” “No,” returned Cæsar,

in an excited manner, “I don't: I want to

act out Gineral Cæsar in good style, but I

ain't goin' to bile under that cussed old

stove for nobody!” This stopped the play,

and the students abandoned theatricals

forthwith.

8. VIII.

COLORED PEOPLE'S CHURCH.

There is a plain little meeting-house on

Barnwell street in which the colored people

—or a goodly portion of them—worship on

Sundays. The seats are cushionless and

have perpendicular backs. The pulpit is

plain white—trimmed with red, it is true,

but still a very unostentatious affair for

colored people, who are supposed to have

a decided weakness for gay hues. Should

you escort a lady to this church and seat

yourself beside her, you will infallibly be

touched on the shoulder, and politely requested

to move to the “gentlemen's side.”

Gentlemen and ladies are not allowed to

sit together in this church. They are

parted remorselessly. It is hard—we may

say it is terrible—to be torn asunder in

this way, but you have to submit, and of

pleasantly.

Meeting opens with an old fashioned

hymn, which is very well sung indeed, by

the congregation. Then the minister reads

a hymn, which is sung by the choir on the

front seats near the pulpit. Then the minister

prays. He hopes no one has been attracted

there by idle curiosity—to see or be

seen—and you naturally conclude that

he is gently hitting you. Another hymn

follows the prayer, and then we have the

discourse, which certainly has the merit of

peculiarity and boldness. The minister's

name is Jones. He don't mince matters at

all. He talks about the “flames of hell”

with a confident fierceness that must be

quite refreshing to sinners. “There's no

half-way about this,” says he, “no by-paths.

There are in Cleveland lots of men who

go to church regularly, who behave well in

meeting, and who pay their bills. They

ain't Christians, though. They're gentlemen

sinners. And whar d'ye spose theyll

fetch up? I'll tell ye—they'll fetch up in

hell, and they'll come up standing, too—

backer? Have I got a backer? Whar's

my backer? This is my backer (striking

the Bible before him)—the Bible will back

me to any amount!” To still further convince

his hearers that he was in earnest, he

exclaimed, “That's me—that's Jones!”

He alluded to Eve in terms of bitter

censure. It was natural that Adam should

have been mad at her. “I shouldn't want

a woman that wouldn't mind me, myself,”

said the speaker.

He directed his attention to dancing,

declaring it to be a great sin. “Whar

there's dancing there's fiddling—whar

there's fiddling there's unrighteousness,

and unrighteousness is wickedness, and

wickedness is sin! That's me—that's

Jones.”

Bosom, the speaker invariably called

“buzzim,” and devil “debil,” with a fearfully

strong accent on the “il.”

9. IX.

SPIRITS.

Mr. Davenport, who has been for some

time closely identified with the modern

spiritual movement, is in the City with his

daughter, who is quite celebrated as a

medium. They are accompanied by Mr.

Eighme and his daughter, and are holding

circles in Hoffman's Block every afternoon

and evening. We were present at the

circle last evening. Miss Davenport seated

herself at a table on which was a tin trumpet,

a tamborine, and a guitar. The audience

were seated around the room. The lights

were blown out, and the spirit of an eccentric

individual, well known to the Davenports,

and whom they call George, addressed

the audience through the trumpet. He

called several of those present by name in

a boisterous voice, and dealt several stunning

knocks on the table. George has

years. He is a rather rough spirit, and probably

run with the machine and “killed for

Kyser” when in the flesh. He ordered

the seats in the room to be wheeled round

so the audience would face the table. He

said the people on the front seat must be

tied with a rope. The order was misunderstood,

the rope being merely drawn before

those on the front seat. He reprimanded

Mr. Davenport for not understanding the

instructions. What he meant was that

the rope should be passed once around

each person on the front seat and then

tightly drawn, a man at each end of the

seat to hold on to it. This was done and

George expressed himself satisfied. There

was no one near the table save the medium.

All the rest were behind the rope,

and those on the front seat were particularly

charged not to let any one pass by

them. George said he felt first-rate, and

commenced kissing the ladies present.

The smack could be distinctly heard, and

some of the ladies said the sensation was

very natural. For the first time in our

envied George. We did not understand

whether the kissing was done through a

trumpet. After kissing considerably, and

indulging in some playful remarks with

a man whose Christian name was Napoleon

Bonaparte, and whom George called

“Boney,” he tied the hands and feet of

the medium. He played the guitar and

jingled the tamborine, and then dashed

them violently on the floor. The candles

were lit and Miss Davenport was securely

tied. She could not move her hands.

Her feet were bound, and the rope (which

was a long one) was fastened to the chair.

No person in the room had been near

her or had anything to do with tieing her.

Every person who was in the room will

take his or her oath of that. She could

hardly have tied herself. We never saw

such intricate and thorough tieing in our

life. The believers present were convinced

that George did it. The unbelievers

didn't exactly know what to think

about it. The candles were extinguished

again, and pretty soon Miss Davenport

an affrighted tone. The candles were lit,

and she was discovered sitting on the

table—hands and feet tied as before, and

herself tied to the chair withal. The lights

were again blown out, there were sounds

as if some one was lifting her from the

table; the candles were re-lit, and she was

seen sitting in the chair on the floor again.

No one had been near her from the audience.

Again the lights were extinguished,

and presently the medium said her feet

were wet. It appeared that the mischievous

spirit of one Biddie, an Irish Miss who died

when twelve years old, had kicked over the

water-pail. Miss Eighme took a seat at

the table, and the same mischievous Biddie

scissored off a liberal lock of her hair.

There was the hair, and it had indisputably

just been taken from Miss Eighme's head,

and her hands and feet, like those of Miss

D., were securely tied. Other things of a

staggering character to the skeptic were

done during the evening.

10. X.

MR. BLOWHARD.

The reader has probably met Mr. Blowhard.

He is usually round. You find him

in all public places. He is particularly

“numerous” at shows. Knows all the actors

intimately. Went to school with some of

'em. Knows how much they get a month

to a cent, and how much liquor they can

hold to a teaspoonful. He knows Ned

Forrest like a book. Has taken sundry

drinks with Ned. Ned likes him much.

Is well acquainted with a certain actress.

Could have married her just as easy as not

if he had wanted to. Didn't like her

“style,” and so concluded not to marry her.

Knows Dan Rice well. Knows all of his

men and horses. Is on terms of affectionate

intimacy with Dan's rhinoceros, and

is tolerably well acquainted with the performing

elephant. We encountered Mr.

entertaining those near him with a full

account of the whole institution, men, boys,

horses, “muils” and all. He said, the rhinoceros

was perfectly harmless, as his teeth

had all been taken out in infancy. Besides,

the rhinoceros was under the influence of

opium, while he was in the ring, which entirely

prevented his injuring anybody. No

danger whatever. In due course of time the

amiable beast was led into the ring. When

the cord was taken from his nose, he turned

suddenly and manifested a slight desire to

run violently in among some boys who were

seated near the musicians. The keeper,

with the assistance of one of the Bedouin

Arabs, soon induced him to change his

mind, and got him in the middle of the

ring. The pleasant quadruped had no

sooner arrived here than he hastily started,

with a melodious bellow, towards the seats

on one of which sat Mr. Blowhard. Each

particular hair on Mr. Blowhard's head

stood up “like squills upon the speckled

porkupine” (Shakspeare or Artemus Ward,

we forget which), and he fell, with a small

ground. He remained there until the

agitated rhinoceros became calm, when he

crawled slowly back to his seat. “Keep

mum,” he said, with a very wise shake of

the head, “I only wanted to have some fun

with them folks above us. I swar, I'll bet

the whisky they thought I was scared!”

Great character, that Blowhard.

11. XI.

MARKET MORNING.

Up, lads, and gaily away!

—Old Comedy.

On market mornings there is a roar and

a crash all about the corner of Kinsman

and Pittsburgh streets. The market building,

so called we presume because it don't

in the least resemble a market building, is

crowded with beef and butchers, and almost

countless meat and vegetable wagons,

of all sorts, are confusedly huddled together

all around outside. These wagons

mostly come from a few miles out of town,

and are always on the spot at daybreak.

A little after sunrise the crash and jam

commences, and continues with little cessation

until 10 o'clock in the forenoon.

There is a babel of tongues, an excessively

cosmopolitan gathering of people, a roar of

wheels, and a lively smell of beef and vegetables.

curative man, the razor man, and a variety

of other tolerable humbugs are in full blast.

We meet married men with baskets in

their hands. Those who have been fortunate

in their selections look happy, while

some who have been unlucky wear a dejected

air, for they are probably destined

to get pieces of their wives' minds on their

arrival home. It is true, that all married

men have their own way, but the trouble is

they don't all have their own way of having

it! We meet a newly married man. He

has recently set up house-keeping. He is

out to buy steak for breakfast. There are

only himself and wife and female domestic

in the family. He shows us his basket,

which contains steak enough for at least

ten able-bodied men. We tell him so, but

he says we don't know anything about war,

and passes on. Here comes a lady of high

degree, who has no end of servants to send

to the market, but she likes to come herself,

and it won't prevent her shining and

sparkling in her elegant drawing-room this

afternoon. And she is accumulating muscle

market.

And here is a charming picture. Standing

beside a vegetable cart is a maiden

beautiful, and sweeter far than any daisy in

the fields. Eyes of purest blue, lips of

cherry red, teeth like pearls, silken, golden

hair, and form of exquisite mold. We

wonder if she is a fairy, but instantly conclude

that she is not, for in measuring out

a peck of onions she spills some of them,

a small boy laughs at the mishap, and she

indignantly shies the measure at his head.

Fairies, you know, don't throw peck-measures

at small boys' heads. The spell was

broken. The golden chain which for a

moment bound us fell to pieces. We meet

an eccentric individual in corduroy pantaloons

and pepper-and-salt coat, who wants

to know if we didn't sail out of Nantucket

in 1852 in the whaling brig fasper Green.

We are compelled to confess that the only

nautical experience we ever had was to

once temporarily command a canal boat on

the dark-rolling Wabash, while the captain

went ashore to cave in the head of a miscreant

sylph who superintended the culinary department

on board that gallant craft. The

eccentric individual smiles in a ghastly

manner, says perhaps we won't lend him a

dollar till to-morrow; to which we courteously

reply that we certainly won't, and

he glides away.

We return to our hotel, reinvigorated

with the early, healthful jaunt, and bestow

an imaginary purse of gold upon our African

Brother, who brings us a hot and excellent

breakfast.

12. XII.

WE SEE TWO WITCHES.

Two female fortune-tellers recently came

hither, and spread “small bills” throughout

the city. Being slightly anxious, in

common with a wide circle of relatives

and friends, to know where we were

going to and what was to become of us,

we visited both of these eminently respectable

witches yesterday and had our fortune

told “twict.” Physicians sometimes disagree,

lawyers invariably do, editors occasionally

fall out, and we are pained to

say that even witches unfold different tales

to one individual. In describing our interviews

with these singularly gifted female women,

who are actually and positively here

in this city, we must speak considerably of

“we”—not because we flatter ourselves

that we are more interesting than people

it is really necessary. In the language of

Hamlet's Pa, “List, O list!”

We went to see “Madame B.” first. She

has rooms at the Burnett House. The

following is a copy of her bill:

MADAME B.

The celebrated Spanish Astrologist, Clairvoyant

and female Doctress, would respectfully

announce to the citizens that she has

just arrived in this city, and designs remaining

for a few days only. The Madame can

be consulted on all matters pertaining to life,

either past, present or future, tracing the

line of life from Infancy to Old Age, particularizing

each event, in regard to Business,

Love, Marriage, Courtship, Losses,

Law Matters, and Sickness of Relatives

and Friends at a distance.

The Madame will also show her visitors

a life-like representation of their Future

Husbands and Wives.

Lucky Numbers in Lotteries can also be

selected by her, and hundreds who have

consulted her have drawn capital prizes. The

for grown persons, male or female,

and children.

Persons wishing to consult her concerning

this mysterious art and human destiny,

particularly with reference to their own individual

bearing in relation to a supposed

Providence, can be accommodated by calling

at Room No. 23, Burnett House, corner

of Prospect and Ontario streets, Cleveland.

The Madame has traveled extensively

for the last few years, both in the United

States and the West Indies, and the success

which has attended her in all places

has won for her the reputation of being the

most wonderful Astrologist of the present

age.

The Madame has a superior faculty for

this business, having been born with a Caul

on her Face, by virtue of which she can

more accurately read the past, present and

future; also enabling her to cure many diseases

without using drugs or medicines.

The Madame advertises nothing but what

she can do. Call on her if you would consult

living.

Hours of Consultation, from 8 A. M. to

9 o'clock P. M.

We urbanely informed the lady with the

“Caul on her Face” that we had called to

have our fortune told, and she said “hand

out your money.” This preliminary being

settled, Madame B. (who is a tall, sharp-eyed,

dark-featured and angular woman, dressed

in painfully positive colors, and heavily

loaded with gold chain and mammoth jewelry

of various kinds) and Jupiter indicated

powerful that we were a slim constitution,

which came down on to us from our father's

side. Wherein our constitution was not

slim, so it came down on to us from our

mother's side. “Is this so?” and we said

it was. “Yes,” continued the witch, “I

know'd t'was. You can't deceive Jupiter,

me, nor any other planick. You may swim

over Hell's-Point same as Leander did, but

you can't deceive the planicks. Give me

yer hand! Times ain't so easy as they has

been. So—so—but 'tis temp'ry. T'wont

may be tramped on to onct or twict, but

you'll rekiver. You have talenk, me child.

You kin make a Congresser if sich you

likes to be. [We said we would be excused

if it was all the same to her.] You kin be

a lawyer. [We thanked her, but said we

would rather retain our present good moral

character.] You kin be a soldier. You

have courage enough to go to the Hostrian

wars and kill the French. [We informed

her that we had already murdered some

“English.”] You won't have much money

till you're thirty-three years of old. Then

you will have large sums—forty thousand

dollars perhaps. Look out for it! [We

promised we would.] You have traveled

some, and you will travel more, which will

make your travels more extensiver than they

has been. You will go to Californy by way

of Pike's Pick. [Same route taken by

Horace Greeley.] If nothin' happens on

to you you won't meet with no accidents

and will get through pleasant, which you

otherwise will not do under all circumstances

however which doth happens to all both

the poor. Hearken to me! There has

been deaths in your family, and there will

be more! But Reserve your constitution

and you will live to be seventy years of old.

Me child, HER hair will be black—black as

the Raving's wing. Likewise black will

also be her eyes, and she'll be as different

from which you air as night and day. Look

out for the darkish man! He's yer rival!

Beware of the darkish man! [We promised

that we'd introduce a funeral into the

“darkish man's” family the moment we

encountered him.] Me child, there's more

sunshine than clouds for ye, and send all

your friends up here.

A word before you goes. Expose not

yourself. Your eyes is saller which is on

accounts of bile on your systim. Some

don't have bile on to their systims which

their eyes is not saller. This bile ascends

down on to you from many generations

which is in their graves and peace to their

ashes.

MADAME CROMPTON.

We then proceeded directly to Madame

Crompton, the other fortune-teller.

Below is her bill:

MADAME R. CROMPTON,

The world-renowned Fortune Teller and

Astrologist. Madame Crompton begs leave

to inform the citizens of Cleveland and vicinity,

that she has taken rooms at the Farmers'

St. Clair House, corner of St. Clair

and Water Streets, where she may be consulted

on all matters pertaining to Past and

Future Events. Also, giving information

of Absent Friends, whether living or

dead.

P.S.—Persons having lost or having property

stolen of any kind, will do well to give

her a call, as she will describe the person or

persons with such accuracy as will astonish

the most devout critic.

Terms Reasonable.

She has rooms at the Farmers' Hotel, as

stated in the bill above. She was driving an

wait half an hour or so for a chance to see

her. Madame Crompton is of the English

persuasion, and has evidently searched many

long years in vain for her H. She is small

in stature, but considerably inclined to corpulency,

and her red round face is continually

wreathed in smiles, reminding one of

a new tin pan basking in the noonday sun.

She took a greasy pack of common playingcards,

and requested us to “cut them in

three,” which we did. She spread them out

before her on the table, and said: “Sir to

you which I speaks. You'av been terrible

crossed in love, and your'art'as been much

panged. But you'll get all over it and marry

a light complected gale with rayther reddish

'air. Before some time you'll have a leggercy

fall down on to you, mostly in solick

Jold. There may be a lawsuit about it

and you may be sup-prisoned as a witnesses,

but you'll git it—mostly in solick Jold, which

you will keep in chists, and you must look

out for them. [We said we would keep a

skinned optic on “them chists.”] You 'as

a enemy and he's a lightish man. He wants

tellink lies about you now in the'opes of

crushin' yourself. [A weak invention of

“the opposition.”] You never did nothin'

bad. Your'art is right. You'ave a great

taste for hosses and like to stay with'em.

Mister to you I sez! Gard aginst the lightish

man and all will be well.” The supernatural

being then took an oval-shaped chunk of

glass (which she called a stone) and requested

us to “hang on to it.” She looked

into it and said: “If you're not keerful

when you git your money you'll lose it, but

which otherwise you will not, and fifty cents

is as cheap as I kin afford to tell anybody's

fortune and no great shakes made then as

the Lord in Heving knows.”

13. XIII.

ROUGH BEGINNING OF THE HONEYMOON.

On last Friday morning an athletic young

farmer in the town of Waynesburg took a

fair girl, “all bathed in blushes,” from her

parents, and started for the first town across

the Pennsylvania line to be married, where

the ceremony could be performed without

a license. The happy pair were accompanied

by a sister of the girl—a tall, gaunt,

and sharp-featured female of some thirtyseven

summers. The pair crossed the line,

were married, and returned to Wellsville to

pass the night. People at the hotel where

the wedding party stopped observed that

they conducted themselves in a rather singular

manner. The husband would take

his sister-in-law, the tall female aforesaid,

into one corner of the parlor and talk earnestly

to her, gesticulating wildly the while.

down” and talk to him in an angry and

excited manner. Then the husband would

take his fair young bride into a corner, but

he could no sooner commence talking to

her than the gaunt sister would rush in between

them and angrily join in the conversation.

The people at the hotel ascertained

what all this meant about 9 o'clock that

evening. There was an uproar in the room

which had been assigned to the newly-married

couple. Female shrieks and masculine

“swears” startled the people at the hotel,

and they rushed to the spot. The gaunt

female was pressing and kicking against

the door of the room, and the newly-married

man, mostly undressed, was barring

her out with all his might. Occasionally

she would kick the door far enough open

to disclose the stalwart husband, in his Gentleman

Greek Slave apparel. It appeared

that the tall female insisted upon occupying

the same room with the newly-wedded pair;

that her sister was favorably disposed to the

arrangement, and that the husband had

agreed to it before the wedding took place,

contract. “Won't you go away now, Susan,

peaceful?” said the newly-married man,

softening his voice.

“No,” said she, “I won't—so there!”

“Don't you budge an inch!” cried the

married sister within the room.

“Now—now, Maria,” said the young man

to his wife, in a piteous tone, “don't go for

to cuttin' up in this way: now don't!”

“I'll cut up 's much I wanter!” she sharply

replied.

“Well,” roared the desperate man, throwing

the door wide open and stalking out

among the crowd, “well, jest you two wimin

put on your duds and go right straight

home and bring back the old man and woman,

and your grandfather, who is nigh on

to a hundred; bring 'em all here, and I'll

marry the whole d—d caboodle of 'em, and

we'll all sleep together!”

The difficulty was finally adjusted by the

tall female taking a room alone. Wellsville

is enjoying itself over the “sensation.”

14. XIV.

FROM A HOMELY MAN.

Dear Plain Dealer,—I am a plain

man, and there is a melancholy fitness

in my unbosoming my sufferings to the

“Plain” Dealer. Plain as you may be

in your dealings, however, I am convinced

you never before had to deal with a

correspondent so hopelessly plain as I.

Yet plain don't half express my looks.

Indeed I doubt very much whether any

word in the English language could be

found to convey an adequate idea of my

absolute and utter homeliness. The dates

in the old family Bible show that I am

in the decline of life, but I cannot recall

a period in my existence when I felt really

young. My very infancy, those brief

months when babes prattle joyously and

know nothing of care, was darkened by

to endure through life, and my youth

was rendered dismal by continued repetitions

of a fact painfully evident “on the

face of it,” that the boy was growing

homelier and homelier every day. Memory,

that with other people recalls so

much that is sweet and pleasant to think

of in connection with their youth, with

me brings up nothing but mortification,

bitter tears, I had almost said curses, on

my solitary and homely lot. I have wished

—a thousand times wished—that Memory

had never consented to take a seat “in this

distracted globe.”

You have heard of a man so homely

that he couldn't sleep nights, his face

ached so. Mr. Editor, I am that melancholy

individual. Whoever perpetrated

the joke—for joke it was no doubt intended

to be—knew not how much truth

he was uttering, or how bitterly the idle

squib would rankle in the heart of one

suffering man. Many and many a night

have I in my childhood laid awake thinking

of my homeliness, and as the moonlight

upon the handsome and placid features

of my little brother slumbering at my

side, God forgive me for the wicked

thought, but I have felt an almost unconquerable

impulse to forever disfigure

and mar that sweet upturned innocent

face that smiled and looked so beautiful

in sleep, for it was ever reminding me of

the curse I was doomed to carry about me.

Many and many a night have I got up in

my night-dress, and lighting my little lamp,

sat for hours gazing at my terrible ugliness

of face reflected in the mirror, drawn to it

by a cruel fascination which it was impossible

for me to resist.

I need not tell you that I am a single

man, and yet I have had what men call

affairs of the heart. I have known what

it is to worship the heart's embodiment

of female loveliness, and purity, and truth,

but it was generally at a distance entirely

safe to the object of my adoration. Being

of a susceptible nature I was continually

falling in love, but never, save with one

single exception, did I venture to declare

walking in a grove. Moved by my consuming

love I rushed towards her, and

throwing myself at her feet began to

pour forth the long pent-up emotions of

my heart. She gave one look and then

“Shrieked till all the rocks replied;”

had seen me leave that grove with a speed

greatly accelerated by a shower of rocks

from the hands of an enraged brother, who

was at hand. That prepossessing young

lady is now slowly recovering her reason

in an institution for the insane.

Of my further troubles I may perhaps

inform you at some future time.

15. XV.

THE ELEPHANT.

Some two years since, on the strength of

what we regarded as reliable information,

we announced the death of the elephant

Hannibal at Canton, and accompanied the

announcement with a short biographical

sketch of that remarkable animal. We

happened to be familiar with several interesting

incidents in the private life of Hannibal,

and our sketch was copied by almost

every paper in America and by several European

journals. A few months ago a

“traveled” friend showed us the sketch in

a Parisian journal, and possibly it is “going

the rounds” of the Chinese papers by this

time. A few days after we had printed his

obituary Hannibal came to town with Van

Amburgh's Menagerie, and the same type

life again.

About once a year Hannibal

And goes bobbin' around,”

ballad. These sprees, in fact, “is what's

the matter with him.” The other day, in

Williamsburg, Long Island, he broke loose

in the canvas, emptied most of the cages,

and tore through the town like a mammoth

pestilence. An extensive crowd of athletic

men, by jabbing him with spears and pitchforks,

and coiling big ropes around his legs,

succeeded in capturing him. The animals

he had set free were caught and restored

to their cages without much difficulty. We

doubt if we shall ever forget our first view

of Hannibal—which was also our first view

of any elephant—of the elephant, in short.

It was at the close of a sultry day in June,

18—. The sun had spent its fury and was

going to rest among the clouds of gold and

crimson. A solitary horseman might have

New England town. That solitary horseman

was us, and we were mounted on the

old white mare. Two bags were strapped

to the foaming steed. That was before we

became wealthy, and of course we are not

ashamed to say that we had been to mill,

and consequently them bags contained flour

and middlin's. Presently a large object

appeared at the top of the hill. We had

heard of the devil and had been pretty often

told that he would have a clear deed and

title to us before long, but had never heard

him painted like the object which met our

gaze at the top of that hill, on the close of

that sultry day in June. Concluding (for

we were a mere youth) that it was an eccentric

whale, who had come ashore near North

Yarmouth and was making a tour through

the interior on wheels, we hastily turned

our steed and made for the mill at a rapid

rate. Once we threw over ballast, after the

manner of ballonists, and as the object

gained on us we cried aloud for our parents.

Fortunately we reached the mill in safety,

a portion of a woodshed on its back. It

was Hannibal, who had run away from a

neighboring town, taking a shed with him.

Drank Standin'.—Col. — is a big

“railroad man.” He attended a railroad

supper once. Champagne flowed freely,

and the Colonel got more than his share.

Speeches were made after the removal of

the cloth. Somebody arose and eulogized

the Colonel in the steepest possible manner

—called him great, good, patriotic, enterprising,

&c., &c. The speaker was here interrupted

by the illustrious Colonel himself,

who, arising with considerable difficulty,

and beaming benevolently around the table,

gravely said: “Let's (hic) drink that sedimunt

standin'!” It was done

16. XVI.

BUSTS.

There are in this city several Italian

gentlemen engaged in the bust business.

They have their peculiarities and eccentricities.

They are swarthy-faced, wear

slouched caps and drab pea-jackets, and

smoke bad cigars. They make busts of

Webster, Clay, Bonaparte, Douglas, and

other great men, living and dead. The

Italian buster comes upon you solemnly

and cautiously. “Buy Napo-leon?” he will

say, and you may probably answer “not a

buy.” “How much giv-ee?” he asks, and

perhaps you will ask him how much he

wants. “Nine dollar,” he will answer always.

We are sure of it. We have observed

this peculiarity in the busters frequently.

No matter how large or small the

bust may be, the first price is invariably

“nine dollar.” If you decline paying this

price, as you undoubtedly will if you are

much giv-ee?” By way of a joke you say

“a dollar,” when the buster retreats indignantly

to the door, saying in a low, wild

voice, “O dam!” With his hand upon the

door-latch, he turns and once more asks,

“how much giv-ee?” You repeat the previous

offer, when he mutters, “O ha!” then

coming pleasantly towards you, he speaks

thus: “Say! how much giv-ee?” Again

you say a dollar, and he cries, “take 'um—

take 'um!”—thus falling eight dollars on

his original price.

Very eccentric is the Italian buster, and

sometimes he calls his busts by wrong

names. We bought Webster (he called him

Web-STAR) of him the other day, and were

astonished when he called upon us the next

day with another bust of Webster, exactly

like the one we had purchased of him, and

asked us if we didn't want to buy “Cole,

the wife-pizener!” We endeavored to rebuke

the depraved buster, but our utterance

was choked and we could only gaze upon

him in speechless astonishment and indignation.

17. XVII.

A COLORED MAN OF THE NAME OF JEFFRIES.

One beautiful day last August, Mr. Elmer,

of East Cleveland, sent his hired colored

man, of the name of Jeffries, to town

with a two-horse wagon to get a load of

lime. Mr. Elmer gave Jeffries $5 with

which to pay for the lime. The horses

were excellent ones, by the way, nicely

matched, and more than commonly fast.

The colored man of the name of Jeffries

came to town and drove to the Johnson

street Station, where he encountered a frail

young woman of the name of Jenkins, who

had just been released from Jail, where she

had been confined for naughtycal conduct

(drugging and robbing a sailor). “Will

you fly with me, adorable Jenkins?” he unto

her did say, “or words to that effect,” and

unto him in reply she did up and say: “My

alluding to a stone jug under the

seat in the wagon, “I follow!” Then into

the two-horse wagon this fair maiden got,

and knavely telling the “perlice” to embark

by the first packet for an unromantic land,

where the climate is intensely Tropical, and

where even Laplanders, who like fire, get

more of a good thing than they want—

doing and saying thus the woman of the

name of Jenkins mounted the seat with the

colored man of the name of Jeffries; and

so these two sweet, gushing children of

Nature rode gaily away. Away towards

the setting sun. Away towards Indiana—

bright land of cheap whiskey and corn

doin's!

18. XVIII.

HOW THE NAPOLEON OF SELLERS WAS

SOLD.

We have read a great many stories of

which Winchell, the great wit and mimic,

was the hero, showing alway show neatly

and entirely he sold somebody. Any one

who is familiar with Winchell's wonderful

powers of mimicry cannot doubt that these

stories are all substantially true. But there

is one instance which we will relate, or

perish in the attempt, where the jolly Winchell

was himself sold. The other evening,

while he was conversing with several

gentlemen at one of the hotels, a dilapidated

individual reeled into the room and halted

in front of the stove, where he made wild

and unsuccessful efforts to maintain a firm

position. He evidently had spent the evening

in marching torchlight processions of

particular time was decidedly and disreputably

drunk. With a sly wink to the crowd,

as much as to say, “we'll have some fun

with this individual,” Winchell assumed a

solemn face, and in a ghostly voice said to

one of the company:

“The poor fellow we were speaking of is

dead!”

“No?” said the individual addressed.

“Yes,” said Winchell; “you know both

of his eyes were gouged out, his nose was

chawed off, and both of his arms were torn

out at the roots. Of course he couldn't recover.”

This was all said for the benefit of the

drunken man, who was standing, or trying

to stand, within a few feet of Winchell, but

he took no sort of notice of it and was apparently

ignorant of the celebrated delineator's

presence. Again Winchell endeavored

to attract his affention, but utterly

failed as before. In a few moments the

drunken man staggered out of the room.

“I can generally have a little fun with a

go in this case.”

“I suppose you know what ails the man

who just went out?” said the “gentlemanly

host.”

“I perceive he is alarmingly inebriated,”

said Winchell; “does anything else ail

him?”

“Yes,” said the host, “HE'S DEAF AND

DUMB!”

This was true. There was a “larf,” and

Winchell, with the remark that he was

sorry to see a disposition in that assemblage

“to deceive an orphan,” called for a light

and went gravely to bed.

19. XIX.

ON AUTUMN.

Poets are wont to apostrophize the leafy

month of June, and there is no denying that

if Spring is “some” June is Summer. But

there is a gorgeous magnificence about the

habiliments of Nature, and a teeming fruitfulness

upon her lap during the autumnal

months, and we must confess we have

always felt genially inclined towards this

season. It is true, when we concentrate

our field of vision to the minute garniture

of earth, we no longer observe the beautiful

petals, nor inhale the fragrance of a gay parterre

of the “floral epistles” and “angel-like

collections” which Longfellow (we believe)

so graphically describes, and which

Shortfellows so fantastically carry about in

their button-holes; but we have all their

tints reproduced upon a higher and broader

canvas in the kaleidoscopic colors with

us, and the beautiful and luscious fruits

which Autumn spreads out before us, and

“Crowns the rich promise of the opening Spring.”

In another point of view Autumn is suggestive

of pleasant reflections. The wearying,

wasting heat of summer and the

deadly blasts with which her breath has for

some years been freighted, are past, and

the bracing north winds begin to bring

balm and healing on their wings. The

hurly-burly of travel, and most sorts of publicity

(except newspapers), are fast playing

out, and we can once more hope to see our

friends and relations in the happy sociality

of home and fireside enjoyments. Yielding,

as we do, the full force to which Autumn

is seriously entitled, or rather to the

serious reflections and admonitions which

the decay of Nature and the dying year

always inspire, and admitting the poet's

decade:

And stars to set,—but all,

Thou hast all seasons for thine own, O Death!”

brighter opening years to those who choose

them rather than dead leaves and bitter

fruits. Thus we can conclude tranquilly

with Bryant as we began gaily with another,—

The innumerable caravan, which moves

To that mysterious realm, where each shall take

His chamber in the silent halls of death,

Thou go not, like the quarry-slave at night,

Scourged to his dungeon, but, sustained and soothed

By an unfaltering trust, approach thy grave

Like one who wraps the drapery of his couch

About him, and lies down to pleasant dreams.”

20. XX.

PAYING FOR HIS PROVENDER BY PRAYING.

We have no intention of making fun of

serious matters in telling the following

story; we merely relate a fact.

There is a rule at Oberlin College that

no student shall board at any house where

prayers are not regularly made each day.

A certain man fitted up a boarding-house

and filled it with boarders, but forgot, until

the eleventh hour, the prayer proviso. Not

being a praying man himself, he looked

around for one who was. At length he

found one—a meek young man from Trumbull

County—who agreed to pay for his

board in praying. For a while all went smoothly, but the boarding-master furnished

his table so poorly that the boarders began

to grumble and to leave, and the other

morning the praying boarder actually

dialogue occurred at the table:

Landlord—Will you pray, Mr. Mild?

Mild—No, sir, I will not.

Landlord—Why not, Mr. Mild?

Mild—It don't pay, sir. I can't pray on

such victuals as these. And unless you

bind yourself in writing to set a better table

than you have for the last three weeks,

nary another prayer do you get out of me!

And that's the way the matter stood at

latest advices.

21. XXI.

NAMES.

Any name which is suggestive of a joke,

however poor the joke may be, is often a

nuisance. We were once “confined” in

a printing-office with a man named Snow.

Everybody who came in was bound to have

a joke about Snow. If it was Summer the

mad wags would say we ought to be cool,

for we had Snow there all the time—which

was a fact, though we sometimes wished

Snow was where he would speedily melt.

Not that we didn't like Snow. Far from it.

His name was what disgusted us. It was

also once our misfortune to daily mingle

with a man named Berry. We can't tell

how many million times we heard him

called Elderberry, Raspberry, Blueberry,

Huckleberry, Gooseberry, etc. The thing

nearly made him deranged. He joined the

to get shot, but had not succeeded at last

accounts, although we fear he has been

“slewd” numerously. There is a good

deal in a name, our usually correct friend

W. Shakespeare to the contrary notwithstanding.

Our own name is unfortunately one on

which jokes, such as they are, can be made.

We cannot present a tabular statement of

the times we have done things brown (in

the opinion of partial friends), or have been

asked if we were related to the eccentric

old slave and horse “liberator” whose recent

Virginia Reel has attracted so much

of the public's attention. Could we do so

the array of figures would be appalling.

And sometimes we think we will accept

the first good offer of marriage that is

made to us, for the purpose of changing

our unhappy name, setting other interesting

considerations entirely aside.

22. XXII.

HUNTING TROUBLE.

Hunting trouble is too fashionable in this

world. Contentment and jollity are not cultivated

as they should be. There are too

many prematurely-wrinkled, long and melancholy

faces among us. There is too

much swearing, sweating and slashing

fuming, foaming and fretting around and

about us all.

“A mad world, my masters.”

People rush out doors bareheaded and

barefooted, as it were, and dash blindly into

all sorts of dark alleys in quest of all sorts

of Trouble, when “Goodness knows,” if

they will only sit calmly and pleasantly by

their firesides, Trouble will knock soon

enough at their doors.

Hunting Trouble is bad business. If we

proud position to become a member

of the Legislature, or ever accumulate sufficient

muscle, impudence, and taste for bad

liquor to go to Congress, we shall introduce

a “william” for the suppression of Trouble-hunting.

We know Miss. Slinkins, who

incessantly frets because Miss Slurkins

is better harnessed than she is, won't like it;

and we presume the Simpkinses, who worry

so much because the Perkinses live in a

freestone-fronted house whilst theirs is only

plain brick, won't like it also. It is doubtful,

too, whether our long-haired friends,

the Reformers (who think the machinery of

the world is all out of joint, while we think

it only needs a little greasing to run in first-rate

style), will approve the measure. It is

probable, indeed, that very many societies,

of are formatory (and inflammatory) character,

would frown upon the measure.

But the measure would be a good one

nevertheless.

Never hunt trouble. However dead a

shot one may be, the gun he carries on

such expeditions is sure to kick or go off

enough, and when he does come receive

him as pleasantly as possible. Like the

tax-collector, he is a disagreeable chap

to have in one's house, but the more amiably

you greet him the sooner he will go

away.

A man in Buffalo—an entire stranger to

us—sends us a quarter-column puff of his

business, with the cool request that we

“copy as editorial, and oblige.” If he does

not eventually subside into a highway robber

it won't be for lack of the necessary

impudence.

23. XXIII.

HE FOUND HE WOULD.

Several years ago Bill McCracken lived

in Peru, Indiana. [We were in Peru several

years ago, and it was a nice place we

don't think.] Mr. McCracken was a

screamer, and had whipped all the recognized

fighting men on the Wabash. One

day somebody told him that Jack Long,

blacksmith at Logansport, said he would

give him (McCracken) a protracted fir of

sickness if he would just come down there

and smell of his bones. The McCracken

at once laid in a stock of provisions, consisting

of whiskey in glass and chickens in

the shell, and started for Logansport. In a

few days he was brought home in a bunged-up

condition, on a cot-bed. One eye was

gouged out, a portion of his nose was

chawed off, his left arm was in a sling, his

pretty badly off himself. He was set down

in the village bar-room, and turning to the

crowd he, in a feeble voice, said, hot tears

bedewing his face the while, “Boys, you

know Jack Long said if I'd come down to

Loginsput he'd whale h—ll out of me; and,

boys, you know I didn't believe it, but I've

been down thar and I found he would.”

He recovered after a lapse of years and

led a better life. As he said himself, he returned

from Logansport a changed man.

24. XXIV.

DARK DOINGS.

Four promising young men of this city

attended a ball in the rural districts not long

since. At a late hour they retired, leaving

word with the clerk of the hotel to call

them early in the morning, as they wanted

to take the first train home. The clerk was

an old friend of the “fellers,” and he thought

he would have a slight joke at their expense.

So he burnt some cork and, with a sponge,

blacked the faces of his city friends after

they had got soundly asleep. In the morning

he called them about ten minutes before

the train came along. Feller No. 1

awoke and laughed boisterously at the

sight which met his gaze. But he saw

through it—the clerk had played his

good joke on his three comrades, and of

course he would keep mum. But it was a

devilish good joke. Feller No. 2 awoke,

the joke, and laughed vociferously.

But he would keep mum. Fellers

No. 3 and 4 awoke, and experienced the

same pleasant feeling; and there was the

beautiful spectacle of four nice young men

laughing heartily one at another, each one

supposing the “urbane clerk” had spared

him in his cork-daubing operations. They

had only time to dress before the train

arrived. They all got aboard, each thinking

what a glorious joke it was to have

his three companions go back to town with

black faces. The idea was so rich that they

all commenced laughing violently as soon

as they got aboard the cars. The other

passengers took to laughing also, and fun

raged fast and furious, until the benevolent

baggage-man, seeing how matters

stood, brought a small pocket-glass and

handed it around to the young men. They

suddenly stopped laughing, rushed wildly

for the baggage-car, washed their faces, and

amused and instructed each other during

the remainder of the trip with some eloquent

flashes of silence.

25. XXV.

A HARD CASE.

We have heard of some very hard cases

since we have enlivened this world with our

brilliant presence. We once saw an able-bodied

man chase a party of little schoolchildren

and rob them of their dinners.

The man who stole the coppers from his

deceased grandmother's eyes lived in our

neighborhood, and we have read about

the man who went to church for the sole

purpose of stealing the testaments and

hymn-books. But the hardest case we