| | ||

The Art Deco Book in France

1. The Livre d'Art OF THE 1920S

I should begin by explaining my choice of topic. Three years ago I wrote a two-volume survey called The Art of the French Illustrated Book, 1700 to 1914, which was published in conjunction with an exhibition at the Pierpont Morgan Library drawn largely from my own collection. In my Introduction I noted that the terminal date had prevented me from dealing with my Art Deco books, which I hoped one day to make "the basis for a small sequel to this history" (1: xxxi). These lectures form the promised sequel.

Once I set to work, however, I discovered the drastic inadequacy of what I had collected. Now, notable Art Deco books, especially in decorated bindings of the period, have never been readily available for examination even in France. Since the dispersal of the late Francis Kettaneh's collection, which provided the backbone of the Grolier Club's exhibition of French Art Deco illustration in 1968, they are still less accessible in the United States. But I persisted, and with the assistance of various institutions and private collectors, I have managed to cover the field. My particular indebtedness is to the Spencer Collection in the New York Public Library, the Frank Altschul Collection at Yale, the Morgan Gunst Collection at Stanford, and the remarkable assemblage of books illustrated by the pochoir process still in the process of formation by Charles Rahn Fry of New York City. These holdings will allow me to display and comment on much unique material in the form of drawings, proofs, and especially bindings.

I can at least claim that my subject is a timely one. The rediscovery of Art Deco in general, which has been proceeding with increasing fervor

These developments have had their impact on rare book sales generally. Parisian dealers, while setting their prices as usual at a point just below that at which no customer would consider buying, remain unexcited. Having dealt continuously with illustrated books of the 1920s since these volumes began to appear, they have their considered views regarding such wares. Moreover, they know how extensive the reserve supply of them must be. Among dealers elsewhere in Europe and in the United States, however, there has been a disposition to move these books up to the level established at Art Deco auctions.

This practice would be legitimate enough, given the importance of Art Deco in the evolution of styles, if the material so offered in fact represented it. But most French illustrated books of the 1920s were largely untouched by Art Deco, just as many decorated morocco bindings of the period were executed by craftsmen who continued to work in an earlier tradition. Moreover, a considerable proportion of the abundant productions of the time, including some of the most elaborate and pretentious, were ill-conceived and poorly carried out. Deprived of the sheltering cloak of Art Deco, most illustrated books of the 1920s require to be appraised individually, with drastically lowered expectations. In view of these conditions, a survey of the field, however tentative and incomplete, would appear to have some practical usefulness.

My perspective is that of a collector who for many years has endeavored to find out as much as he could about French illustrated books of the last three centuries. Concerning the volumes of the 1920s the sources of information for the most part are contemporary with the period itself, since these books haven't as yet attracted much attention from modern

I propose to limit my account of the Art Deco book in France to the 1920s, or at least to the years 1919 to 1930. This decade was its heyday, the years which saw the appearance of most of the best work of its representative masters. Moreover, the period saw the reemergence of the livre d'art, as the fine illustrated book for collectors was then called, on a quite unprecedented scale. This crescendo of production led to notable achievements as well as deplorable follies and concluded with a catastrophic debacle. I shall thus be dealing with a self-contained episode in the history of book collecting, an episode which embodies some of the elements of high drama.

The world of fine illustrated books before the first World War was flourishing but limited. Its requirements were met by perhaps 15 publishers, and its clientele hardly extended beyond a few hundred collectors, most of them well-to-do men of affairs. Prominent on the scene were the Societies of Bibliophiles, under whose aegis were published many of the best books of the time in editions of from 75 to 150 copies. A relatively small number of illustrators, printers, and binders served the needs of what in the perspective of later developments came to seem almost a closed circle. Nonetheless, superb books appeared, though it is true that a few of the most outstanding were published by outsiders such as Ambroise Vollard.[1]

The conditions imposed by the first World War laid a virtual embargo on the publication of livres d'art. The apparatus that produced them fell apart, the collectors who acquired them had other preoccupations,

The hectic aspects of Paris during the 1920s which caused the decade to be called les années folles will figure in my chronicle chiefly as they are reflected in the work of George Barbier. Yet the temper of the age does much to explain the conditions which governed the publication of livres d'art. If rampant prosperity combined with a post-War release from inhibitions to encourage the pursuit of pleasure, these factors stimulated as well an eager desire for luxurious possessions, among them fine books. Nor did bourgeois prudence provide an effective check, since the soundness of the franc was an open question. One observer estimated, indeed, that the public for livres d'art grew ten-fold after the War.[4] Clément-Janin discerned three kinds of enthusiasts in this "prodigious development" of book collecting: (1) major collectors prepared to spend 1000 to 5000 francs on a livre d'art limited to 150 copies or fewer, (2) middle-range collectors who would pay up to 500 francs for a book limited to not more than 500 or 600 copies, and (3) lesser collectors able to spend 40 to 100 francs for mass-produced illustrated books in editions of not more than 3000 copies (2: 152-153). Not only were these new collectors numerous and diverse, for the most part they were also undemanding. As long as the mandatory features of the livre d'art were present—special paper, illustrations, and a limited edition—they were easily satisfied.

Attracted by this large and ready market, publishers multiplied apace, and so did the books they published. Among those protesting against this incontinence was the art critic Jacques Deville, who permitted himself the following tirade:

With the field of book illustration so vastly enlarged, many new artists were drawn into it. These recruits were of uneven quality, as Raymond Hesse demonstrates from the example of books with original wood engravings, for some years after the War the kind of illustration most in favor with collectors. Though illustrators like Louis Jou, Carlègle, and Hermann-Paul produced work of distinction, wood engravings, which can be printed conjointly with text, were also the least expensive adornment that was acceptable in collectors' books, and when publishers avid for profit employed journeymen artists, untrained in the craft, the results were usually lamentable (pp. 150-151).

In his book of 1927 on 19th and 20th century livres d'art, Hesse drew a devastating picture of the contemporary publishing scene. A year later, when he wrote a volume entirely concerned with the post-War book, he had been led by further study to this more balanced comparison of the pre-War and post-War book:

The two periods differ as an English garden does from a virgin forest. In the one: order, method, reason; in the other nature, color, noise, confusion. You walk through the first in entire safety—nothing unexpected but no monsters or wild beasts; in the second, besides unfamiliar and splendid landscapes, you run the constant risk of falling into some mudhole.[6]

One final element in the collecting scene of the 1920s needs to be considered, the extent to which it was affected by speculation. Like other valuable objects, livres d'art could be seen as a hedge against inflation. As in our own time, a collector who bought on publication a book which

Yet this is not the whole story. Even if the possessors of livres d'artwere not conscious speculators, they went on collecting in part because they had more faith in their books than in a declining franc. This judgment seemed to be confirmed in 1928 when the franc was devalued by 4/5ths (from 19.3 to 3.92 cents) yet the value of livres d'art did not diminish. So it was that, despite uncertainties and reverses, the growth of book production and collecting continued unabated. As late as 1928 Clément-Janin expressed "an absolute faith in the persistence of the movement which has carried book collecting to its current flourishing state." To his mind its soundness had been demonstrated during the great monetary crisis wherein was achieved "that profound transformation, that union of the aesthetic and the financial, . . . [which] makes contemporary book collecting durable" (2: 197, 199).

By the winter of 1930-31, before these words were published, the world-wide depression heralded by the Wall Street crash of 1929 had struck France as well. In the first issue of Le bibliophile for February 1931, Marcel Valotaire wrote despairingly of "this crisis of the livre d'art,the very idea of which weighs heavily on the mind as much of collectors as of printers, publishers, and book-sellers" (p. 31). It had been discovered that in these desperate times the world of rare books was doubly vulnerable. If automobiles ceased to sell, it was because the market was saturated, not because the product was unsatisfactory. The years since The War, however, had seen an absurd multiplication of alleged livres d'art,the work of untrained publishers, designers, and illustrators. While money was plentiful, undiscriminating collectors had freely bought these regrettable productions. But now the book trade was faced with a comprehensive failure of confidence, with an accompanying "disgust, disdain, repudiation by purchasers in the face of the poor, or at least doubtful

EN ÉCOUTANT SATIE

1920

MODES ET MANIÈRES D'AUJOURD'HUI

Pl. XI

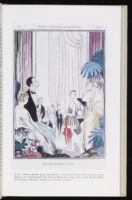

PLATE 1. Robert Bonfils, plate from Modes et manières d'aujourd'hui, 9e anné, 1920,[1922] (1.18). Reproduced from Charles Rahn Fry's copy, now in the Charles Rahn Fry Pochoir Collection, Princeton University Library.

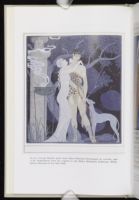

PLATE 2. George Barbier, plate from Albert Flament's Personnages de comédie, 1922 (2.16). Reproduced from the original in the Elisha Whittelsey Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

PLATE 3. François-Louis Schmied, text and vignette from Histoire de la princesse Boudour, translated by J.-C. Mardrus, 1926 (3.24). Reproduced from the original in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

PLATE 4. François-Louis Schmied, plate from La création, translated by J.-C. Mardrus, 1928 (3.30). Reproduced by permission of The Pierpont Morgan Library, Bequest of Gordon N. Ray, 1987.

PLATE 5. Jean-Émile Laboureur, plate from Jean Valmy-Baysse's Tableau des grands magasins, 1925 (4.27). Reproduced by permission of The Pierpont Morgan Library, Bequest of Gordon N. Ray, 1987.

PLATE 6. Pierre Begrain, lower doublure in his album of maquettes, 1929 (5.26). Reproduced by permission from the original in the Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

PLATE 7. Rose Adler, upper cover and spine of binding (1931) on Tristan Bernard's Tableau de la boxe, 1922 (5.37). Reproduced by permission from the original in the Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

PLATE 8. François-Louis Schmied, upper cover of binding on Le cantique des cantiques,translated by Ernest Renan, 1925 (5.45). Reproduced from the original in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

The history just rehearsed makes it evident that any survey of the livres d'art of the 1920s must begin with the question: what proportion of these hundreds of titles (well over a thousand, indeed, if demi-luxevolumes are included) deserves attention today? The answer is, a considerable number, for if the period produced many bad books, it also produced many good ones. At the risk of seeming arbitrary, I propose several categories of worthy survivors.

Pride of place must be accorded to livres de peintre, though in fact the decade saw the appearance chiefly of lesser works of this kind. Only in 1929 and 1930 did the splendid series of major books with original graphics by great painters, the glory of 20th century French book production, really get under way. Charles-Louis Philippe's Bubu de Montparnassewith etchings by Dunoyer de Segonzac was published in the former year, Apollinaire's Calligrammes with lithographs by de Chirico and Eugène Montfort's La belle enfant with etchings by Dufy in the latter.[9] It should be noted that collectors in general were hardly more welcoming to the livre de peintre in the 1920s than they had been before the War. The set of their minds on this topic is exampled in some remarks of Marcel Valotaire, then one of the most knowledgeable and influential of writers on the livre d'art. He wrote of the designs of Laboureur that they are

decorative in their drawing, decorative in their rendering. They are not painter's engravings—an abomination in a book!—, they are the engravings of a graphic artist, established with that solid balance which is the most substantial tie between image and type-page: in a word they are perfect illustrations.[10]

Then there were the established illustrators who resumed their careers after the War. The most distinguished was Maurice Denis, who

Chahine and Jouas also played important roles in the revival of etching. Notable among the colleagues who joined them in displaying the scenery, the architecture, and to a lesser extent the people of France, sometimes working alone, sometimes banded together in the publications of the Société de Saint Eloi, were Auguste Brouet, P.-A. Bouroux, André Dauchez, Pierre Gusman, and towards the end of the decade, Albert Decaris.

Original wood engraving was even more central than etching to the livre d'art, not only in the illustrations of such men as Carlègle and Hermann-Paul, but also in the more comprehensive contributions of three artist-craftsmen who had been trained as wood engravers, François Louis Schmied, Louis Jou, and Jean-Gabriel Daragnès. The three latter were the leading architectes du livre of the time, that is to say workers capable by themselves of creating all the components of a livre d'art.

As colored illustrations came gradually to predominate over those in black and white in the middle and later 1920s, the ascendancy of Schmied and George Barbier was confirmed, the former as the master craftsman of wood engravings printed in color, and the latter as the supreme color stylist, whether his designs were rendered by engraving or by pochoir.Guy Arnoux, Pierre Brissaud, Umberto Brunelleschi, Pierre Falké, Paul Jouve, Georges Lepape, Charles Martin, André-Édouard Marty, and Sylvain Sauvage also stand out for their work in this line.

A number of artists took as their starting point the rejection of the literal detail favored by most pre-War illustrators. Instead they turned to quick, vivid sketches of contemporary life, often accompanying texts by such new novelists as Francis Carco, Jean Giraudoux, Pierre MacOrlan, and Paul Morand. In this group were Gus Bofa, Chas Laborde, Dignimont, and Vertès. Literal realism was equally repugnant to the artists who imposed individual styles of calculated distortion on their subjects. Laboureur was preeminent here, though he had found a formidable rival in Alexeieff by the end of the decade.

Though the best work of all of these artists still deserves the collector's attention, my consideration must be limited to those among them in whose books the Art Deco style is most pronounced. The three lectures following will accordingly center on Barbier, Schmied, and Laboureur, with a final discourse concerned chiefly with Pierre Begrain, the master

Since the incontestable mark of Art Deco in the livre d'art was its emphasis on decoration as opposed to illustration, Schmied's early work, in which the representational element is minimal, offers its purest exemplification. In his later books Schmied supplements decoration with illustration, though he rarely allows the latter to predominate. Abstract decoration was not to Barbier's taste, but throughout his work representational subjects are subordinated to decorative treatment. No doubt his designs are sufficiently striking in conception, but they make their impression above all by their decorative values.

The connection with Art Deco of a third kind of livre d'art, which I shall represent through Laboureur, cannot be made so directly. The book had an important place in the great Exhibition of Decorative and industrial Art held in Paris during 1925. The criterion that dictated the choice of examples to be shown, however, was not so much their decorative qualities as their modernity. Article IV in the general rules of the Exhibition provided that only works of "novel inspiration and real originality"[11] were to be admitted. The French illustrated books displayed had been chosen primarily to demonstrate the variety of techniques and talents of the day. In reviewing these selections the anonymous author of volume 7 of the Rapport général of the Exhibition, that devoted to the book, offers some enlightening comments. While according Schmied more space than any other book-artist, he is at pains to point out at length the surprising ways in which the decorative spirit had affected the vision of other illustrators. "This influence has its part in the tendencies [of the time] towards distortion, in all the liberties that an artist takes with his subject, in the increasingly symbolic character of the design." Moreover, as the pace of modern life grows increasingly rapid, it has to be set down with the briefest of notations. "Accessories are suppressed, the design is reduced to the minimum of lines needed to render it visible at a glance."[12] Laboureur, better than any other book artist of the 1920s, exemplifies these characteristics.

With decorated bookbinding we are back on firmer ground. The work of Pierre Begrain, like that of his numerous imitators, was assertively decorative in nature. Indeed, fine binding during this period was dominated by the growing ascendancy of the Art Deco style after its appeal was demonstrated in the Exhibition of 1925.

With these generalities out of the way, I can turn at last to the books

Perhaps Art Deco is displayed in its purest form in the design portfolios of the 1920s. Their plates were executed by pochoir, that is to say, they were illuminated—to use the word favored by Jean Saudé, the master of pochoir—by water color or gouache through the use of stencils. In conception and layout these portfolios can be traced back to the celebrated Grammar of Ornament by Owen Jones, which appeared in 1856. An important intermediate work was Eugène Grasset's La plante et ses applications ornementales, published in two series in 1896 and 1898. Where Jones had endeavored to classify and illustrate every type of ornament, Grasset turned from man-made inventions to natural forms. His plates, which were drawn by his students, continue Jones's arrangement of several patterns to the page, and they are sometimes varied by the superimposition of objects decorated with these patterns (a vase, a [1.1] pitcher) or shaped in their image (a candlestick, a chair). In the plate shown (first series, plate 66) the object is a mosaic bookbinding.

Grasset's portfolios are a monument to Art Nouveau, exhibiting the various possibilities of flore ornementale. E. A. Séguy's Floréal of 1914 [1.2] also takes its departure from the plant, but as may be seen from plate 17 its designs are adapted with such verve and freedom that the Art Nouveau element has virtually disappeared. Moreover, its pochoir plates, with their subtle gradation of color, exist in a different world from the process reproductions of Grasset's book. A plate (plate 19) from a representative Art Deco portfolio of the 1920s affords a suitable conclusion to this topic. [1.3] Natural objects are still the basis for the drawings in Edouard Bénédictus' Variations of 1923, yet they tend increasingly towards abstract forms, and Saudé's pochoir work, which makes use of a wide gamut of colors including silver, is even richer than that in Floréal. I shall not be returning to

The first landmark in the high fashion tradition which led to Art Deco illustration was Les robes de Paul Poiret of 1908. The great couturier, who had left Worth's in 1904 to establish his own firm, was already famous for the uncorsetted freedom of his novel creations, which women everywhere found distinctive and flattering. In commemoration of his success Poiret commissioned Paul Iribe, one of his many artist friends, to prepare a luxurious album devoted to his work. Iribe focussed [1.4] attention on Poiret's gowns by rendering them in pochoir against rudimentary backgrounds of black and white. There is no pretence on the part of the artist that the figures presented are anything but models.

Three years later appeared a still more sumptuous sequel called Les choses de Paul Poiret vues par Georges Lepape. When Poiret asked Lepape to undertake the volume, the young painter brought him four designs, charming in their simplicity, but also intended to depict models. These are reproduced at the end of the album. After he was shown Poiret's creations, however, he was asked to give his fancy free rein, with varied and engaging results that go far beyond a fashion parade. None of his drawings is like any other in conception, but all are linked in style. Lepape renders even better than Iribe the supple elegance that was Poiret's trademark, yet his most striking design is devoted to another [1.5] house specialty, the turban. As Poiret had predicted, the album made Lepape's reputation.

These two albums had been devoted to a single couturier, if admittedly the best known. La gazette du bon ton, which began to appear in 1912 and continued until 1926, though with an intermission of nearly six years following the outbreak of the War, took the whole world of fashion as its province: Doucet, Paquin, Worth, and the rest, as well as Poiret. At the heart of each issue were 10 pochoir plates, but there were also essays, intended to amuse rather than to inform, on various articles of apparel, on the accoutrements of high life, indeed on choses d'élégance in general. There was a monthly review of theatrical costumes and settings, as well as a column of gossip devoted to fashion and good taste. The text of these pieces was made attractive by pochoir vignettes executed as carefully as the plates. In sum, the magazine represented a way of life, however rarefied and specialized.

Lucien Vogel was already known as the editor of Art et décoration

La gazette du bon ton from its origin was one of the most sought after of fashion publications. Its success, of course, was owing principally to its plates, which are not only records of the dress of the time but also fresh and attractive compositions in themselves. Sometimes they have a [1.6] dramatic element as well. In Lepape's design, "Le jaloux: robe du soir de Paul Poiret" (April 1913), a pretty girl is wooed by an admirer while her elderly protector clenches his fist in rage. The vignettes in the text [1.7] are often true illustrations, as is the case with the scenes from Boris Gudonovwith which Marty illustrates an article on the Ballets Russes of June 1913 (pp. 246-247). Altogether, the style and format of La gazette du bon ton presage what the Art Deco book would become when freed from the fashion straight-jacket.

A second significant fashion publication of the period was the almanac Modes et manières d'aujourd'hui, a slim annual with 12 pochoirplates. Each of its three pre-War volumes had a different illustrator:Lepape in 1912, Martin in 1913, and Barbier in 1914. Their drawings are more ingeniously elaborated than those for La gazette du bon ton. [1.8] Indeed, "L'Ilot" (plate 7) in Barbier's volume may more properly be compared with his depiction of the ballet, "Le spectre de la rose," of the same year, so little is his focus on the bathing dress displayed and so much on the scene of impending seduction. The essentially literary nature of

The imposing pre-War albums devoted to dance and the theatre were inspired for the most part by the Ballets Russes, whose Parisian triumphs had begun in 1909. George Barbier haunted these performances, to which in 1913 and 1914 he devoted collections of drawings, the first concerned with Nijinsky, the second with Tamara Karsavina. These albums have a prominent place in ballet history, but their strongest interest lies elsewhere. Subordinating the opulence of the ballets' productions, but conveying their strangeness and mystery, he concentrated his attention on the principal dancers. As his fellow spectator and devotee Paul Droutot observed, he showed, not gods in their accustomed mythological roles, but "young men and women raised to divine status by their ravishing beauty. You can feel them live, that is to say, love, desire, leap; they are nothing but muscles, supple exertions, nerves, moments of rest between violent gratifications."[14]

Nijinsky was the particular object of Barbier's admiration. Like Francis de Miomandre, who wrote the introduction to his Dessins sur les danses de Vaslav Nijinsky, Barbier saw him as unique among artists, "of another essence from ourselves." In his 12 pochoir plates he showed Nijinsky to be as much a mime as a dancer, adapting himself even in physical appearance to each new role. So the stalwart Ethiopian slave of [1.9] "Sheherazade" became the elusive boy of "Le spectre de la rose."[15]

Album dédié à Tamar Karsavina is Barbier's early masterpiece. Its cover design pays homage to Beardsley, another master of decorative art, and its 12 pochoir plates depict Karsavina in her principal parts. That their purpose is again to stir the emotion and delight the eye of the [1.10] viewer, not to document the performance, is demonstrated by "Le spectre de la rose," glimpsed at the moment when the phantom lover, of whom the young girl has dreamed after the ball, is about to disappear as the rose drops from her hand.

Even more lavish are two further albums, Les masques et les personnages de la comédie italienne, which was published in 1914, with 12 pochoir plates by Brunelleschi, and Sports et Divertissements, in which the score by Erik Satie and 20 pochoir plates by Charles Martin are dated 1914, though the album seems to have appeared at a later date. In his masked figures from an imaginary commedia dell'arte troupe Brunelle- [1.11] Schi emphasizes costume and setting. As "Arlequin" reveals, they are

Finally, there were a few significant illustrated books in which the Art Deco style already predominates published in 1914 or earlier. Francis Jammes' Clara d'Ellebeuse, illustrated by Robert Bonfils, appeared in 1912; Balzac's Le père Goriot, illustrated by Pierre Brissaud, in 1913;and Le cantique des cantiques and Makéda, reine de Saba, chroniqueéthiopienne, both illustrated by Barbier, in 1914. Bonfils, Barbier, and Scmied also had major books in progress on which they were able to work intermittently during the War. Otherwise nothing significant was to come of the preparations that have been described until the end of the decade.

Indeed, the production of collectors' books of any kind over the next four years was minimal. For the soldier-artist, even one who found inspiration in war-time conditions, only the simplest means were available. Yet Laboureur, for example, worked out his cubist style in makeshift albums of wood engravings like Types de l'armée américaine en France (1918) and Images de l'arrière (1919), where he found satisfaction in glimpses of characters from the A.E.F. and the behind-the-lines activities [1.13] of Allied soldiers. Witness a scene of black dock-workers in the former album. Meanwhile, the publisher Meynial had revived the almanac with the publication on Christmas day 1916 of the first volume of La guirlande des mois. This small book is better described as a war-time keepsake thana publication of high fashion, since soldiers back from the front share [1.14] Barbier's five pochoir plates with elegant ladies. There is even an Art Deco battle scene (p. 40). In its miniature way La guirlande des mois is a livre de luxe, but when Meynial replaced it with Falbalas et Fanfreluchesin 1922, it was not without a deprecatory allusion in the final volume to "the artistic character of a publication produced during the War."[16]

If a World War had been the least propitious of all settings for illustrated books, peace-time, when it came, promised to be the most propitious. For Art Deco books Robert Bonfils was the artist who led the way

After his apprentice years in Paris, Bonfils occupied himself with painting, sculpture, and especially the decorative arts. A friend of those days described him as "a tall young man, naturally affable, restrained in gesture, with a grave and musical voice." He passed his days "looking about him, plucking the flower from everything, with an elegant nonchalance. He did not think it frivolous to paint his reveries on the leaf of a fan."[17] From these casual beginnings he went on to a notable career in the decorative arts which extended to designs for porcelain, clothes, fabrics, even tapestries. But the principal focus of his activities was book illustration and binding design.

A man of broad culture, he fell into the habit of drawing in the margins of his favorite poems and stories, and when he turned to book illustration, he thought of his designs as a continuation of this practice. His first book of importance was Francis Jammes' Clara d'Ellebeuse of 1912. Its success led in 1913 to commissions for Henri de Régnier's Les rencontres de monsieur de Bréot and Gerard de Nerval's Sylvie, the latter from the distinguished publisher François Bernouard, hailed by Raymond Hesse as "one of the inspirers of the great `decorative arts effort of 1925' " (p. 146). The war deferred the appearance of these books until 1919. Verlaine's Fêtes galantes with Bonfils' designs appeared in 1915, and "Lover's" Au moins soyez discret in 1919. Sylvie had engravings printed in three colors; the other four volumes were illustrated by pochoir over wood engravings printed in a single color.

Having selected slight but agreeable texts, often with 18th century settings, Bonfils was under no obligation to individualize the figures in them or to present these figures in scenes of dramatic conflict. Instead he could use their activities as occasions for the sympathetic decoration of his pages. He did this for the most part through vignettes, sometimes serving as simple ornaments, sometimes of ampler proportions. Effortless improvisations in appearance, they represent in fact the nicest calculations

Two albums of the period are of particular interest because they show Bonfils working through plates rather than vignettes and as an inventor rather than a commentator. The seven pochoir plates of Divertissements des princesses qui s'ennuient are perhaps his most ambitious drawings, on a scale and accorded a fullness of treatment unmatched elsewhere in his work as an illustrator. Their subject is the amusements of three young ladies at a country house. In keeping with his epigraph from Mallarmé, "Princesse, nommez-nous berger de vos souris," Bonfils treats them with indulgence, but does not disguise the languor of their luxurious lives. Still, it is the opportunity for piquant yet harmonious Art Deco com- [1.17] positions, such as "La promenade" (plate 1), which chiefly interests him.

The volume allotted to Bonfils in Modes et manières d'aujourd'huiis dated 1920 on the title page, though it did not appear until 1922. Its 12 pochoir plates are more fully developed than is usual with the artist. They have no theme, but their emphasis is rather on manners than on fashion, almost leading one to question Robert Burnand's insistence that "no designer is less documentary than Bonfils."[18] Among the aspects of post-War French life presented are the singing of the "Marseillaise" at a theatre, bargain day in a department store, and a family in mourning which watches a military parade from a balcony. Like the other plates, [1.18] the evening party of "En écoutant Satie" (plate 11) is an exercise in perspective.

After 1928 Bonfils illustrated few books. His time was given over to his students at the École Estienne, where he was Professeur de Composition Décorative, and to the writing of a learned manual on La gravure et le livre, which was published in 1938. One may regret that this book is devoted almost exclusively to technical matters, though the author's predilections emerge when he praises original graphics, with their life and spontaneity, as a quick way "for the artist to fix his emotions" (p. 102). Bonfils is one of the most innovative and delightful of Art Deco illustrators. Appreciation of his slim, elegant quartos is bound to increase.

See Gordon N. Ray, The Art of the French Illustrated Book, 1700 to 1914 (2 vols.; New York and Ithaca, 1982), 2; 372-382, 497-498.

Grappe's introduction to Très beaux livres . . . composant la bibliothèque de M. R. Marty (Paris, 1930), p. ii. This is the auction catalogue for a sale at the Hôtel Drouot on 10 13 February 1930.

On the collapse of the rare book market and its consequences, see also Jean Bruller, "Le livre d'art en France: essai d'un classement rationnel," Arts et métiers graphiques, 26 (15 November 1931), 41-66.

Rapport général de l'exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes, Paris, 1925, 7 (Paris, 1929), 51.

I have used the English edition of Barbier's album: Designs on the Dances of Vaslav Nijinsky, translated from the French by C. W. Beaumont (London, 1913).

2. George Barbier

My subject today is George Barbier, the direct inheritor of the tradition of pre-1920 illustration traced in my first lecture. By epitomizing the more refined fantasies of the Parisian world of pleasure during the following decade, he became the most haunting of Art Deco book artists. From a consideration of Barbier's career I'll proceed to a discussion of pochoir, the stencil process which he supported by employing it, despite the prevailing disapproval of bibliophiles, in several of his major works.

Jean-Louis Vaudoyer, the most reliable source for what little information is available about Barbier's early years,[19] relates that he was born in Nantes on 10 October 1882 of a good bourgeois family. After leaving school, where he took the drawing prize year after year, he studied design with local artists. Vaudoyer speculates that the old buildings of the city to which Auguste Lepère was to pay tribute in Nantes en dix-neuf cent, must have awakened in him a sense of the past, just as the paintings of its well-stocked museum, where Watteau and Ingres were represented, must have nourished his artistic vocation. He found a patron in A. Lotz-Brissonneau, a leading industrialist of Nantes who was later to compile the standard catalogue of Lepère's etchings and wood-engravings.

By 1908 Barbier was in Paris, working with Jean-Paul Laurens at the École des Beaux-Arts.[20] He haunted the Louvre, applying himself particularly to the collections of Greek antiquities. When Vaudoyer met [2.1] Barbier in 1910, he found him to be "a tall, elegant blond young man quiet and reserved" (p. 8). Indeed, Vaudoyer took him for an English man especially since he then signed his drawings "E.-W. Larry." At his first exhibition at the Boutet de Monvel gallery during the following year his water colors were grouped by categories which matched his predominant interests: Greek dancers, dancers from the Ballets Russes, and "Belles du Moment." Pierre Louÿs, who wrote the preface to the exhibition's catalogue, praised Barbier for having captured the Hellenic spirit with no taint of Roman influence. "Not one of his figures could appear on an authentic Greek vase. But they are part of the same line. It is not imitation, it is continuation."[21]

Barbier was now fairly launched on his career. We have already seen how his Ballets Russes albums, his depictions of "Belles du Moment"

Of the many titles in Barbier's bibliography it will be necessary to restrict discussion to the most considerable. Those published during the decade of the War have been cited in the previous lecture. Beginning in 1920 his major books were:

Falbalas et fanfreluches, 5 volumes, 1922-1926

Albert Flament, Personnages de comédie, 1922

Pierre Louÿs, Les chansons de Bilitis, 1922

Maurice de Guérin, Poèmes en prose, 1928

Verlaine, Fêtes galantes, 1928

Marcel Schwob, Les vies imaginaires, 1929

Choderlos de Laclos, Les liaisons dangereuses, 1934.

Mention will also be made of the albums in which his work for the theatre is reproduced and of representative titles among the several demi-luxe volumes, typically issued in editions of 1000 copies, to which he turned his hand.

The 16 engraved plates of Le bonheur du jour, ou les grâces à la mode,which were colored by pochoir, are among the largest and most carefully meditated of Barbier's designs. So ambitious was this album, indeed, that it took him from 1920 to 1924 to complete it to his satisfaction.[22] A study both of fashion and of manners, it was offered to those who like to link the present with the past by comparing them even in so frivolous a matter as costume as well as to inquiring observers of the current scene. Barbier begins his introduction with a selective summary of fashion illustration from the 16th century on, finding a specific predecessor for his own work

The period was very like our own, for fear heightens pleasure. These dandies[incroyables] and their ladies [merveilleuses] danced at Tivoli, the allies crowded the galleries of the Palais Royal, the doors of gambling halls and houses of ill fame stood ajar. . . . In our time a similar impatience fills the dancers. Couples, softly embracing, sway to the fluid rhythm of the tango, keeping time to raging cymbals.

By showing the dress, the accoutrements, the interiors of his age, Barbier expected to catch its spirit as well:

The pages that follow are intended to evoke the ostentatious pomp of the year of peace 1920, . . . everything that glitters, everything that burns, everything that at once annoys and pleases. . . . You will find here lacquer furniture, pekinese dogs, jade rings, and rivulets of pearls, nothing will be neglected that might please you, for we humbly solicit the approval of the frivolous and the indulgence of the wise, seeking to please the one and to amuse the other. (pp. 1-2)

On the title page one of Barbier's distinctive cupids holds a cornucopia from which pour such trifles as powder puffs, gloves, fans, and masks. The early plates emphasize fashion on the pattern of Incroyables et merveilleuses, though the manners of the day are not neglected. Theartist's mention of a "hermaphrodite couple" is borne out by the contours and coiffures of the figures in plates 1 and 5, "Les alliés à Versailles" [2.2] and "L'Amour est aveugle." Plates 6 to 9 offer stunning "interiors in the taste of the day, walls lit-up, shadowed mirrors, irresistible divans, veiled lights, rooms invented for idleness and pleasure by a decorator-poet, [2.3] charming and uninhabitable." In "Minuit! . . ou l'appartement à la mode" (plate 7), one should not fail to notice that it is a book by DeQuincey which has brought the young lady to her state of comic alarm. [2.4] The design is thus the natural prelude to "Chez la marchande des pavots" (plate 8), in which androgynous opium-smokers of 1920 offer a languorous contrast to the robust dandies of 1814 evoked by Barbier in his Intro- [2.5] duction. The magnificent lacquer screen of "Le goût des laques" (plate 9) distracts attention even from the plate's silver and golden gowns and jade and pearl ornaments. In his final designs, composed in 1924, Barbier goes well beyond the plan with which he began his series. No longer content with intimate interiors, he now shows the spectacle which society [2.6] provides for the public, at the beach in "Au lido" (plate 14) and at the [2.7] break-up of an evening party in "Au revoir" (plate 16). Put on their implications, these panoramas epitomize the ambiguities of a little world whose arrogance matches its elegance.

Closely associated with Le bonheur du jour, both in date and in conception, is Falbalas et fanfreluches, almanach des modes présentes, passées et futures. These five volumes, which appeared between 1922 and 1926, were the publisher Meynial's lavish peacetime sequel to La guirlande des mois. They contain 60 pochoir plates, as well as a decorative cover design and an amusing title-page vignette for each volume. [2.8] Seeking to preserve for himself complete freedom of choice, Barbier [2.9] took all costume for his province. No doubt contemporary France would most often claim his attention, but he was at liberty to "ransack the ages and spoil the climes." The Comtesse de Noailles, who introduced the first volume, told the artist: "You want us to travel together, you, your readers, and I, into the hidden and always changing land of dress, and I gladly admit that fashion, with its audacities, its fantasies, its reticences, has the same possibilities as a voyage around the world, that it teaches like history, sets us dreaming like the seasons, softens, delights, saddens through love like poetry" (1: 4).

This is surely the perspective from which to appreciate Falbalas et fanfreluches, despite the assertive frivolity of its title, for the designs go far beyond its promised ripper and frills. Each plate is a carefully developed tableau, though on a scale much less ambitious than in Le bonheur du jour, which has points of interest beyond its brilliant depiction of costume and setting. Barbier's usual subject is a love scene, some piquant situation which he can enliven with the freshness and sensual appeal of youth. Indeed, in his historical plates, which range throughout Europe and North America, he rarely chooses any other. Typical is [2.10] "Gentils propos" from the volume for 1922, placed in 19th century Czechoslovakia.

The majority of Barbier's drawings are devoted to the France of his own day, and among them are to be found some memorable inventions. [2.11] Consider "Le soir" in the volume for 1926. The subject is a jazz-age couple before a lacquer screen, but the viewer's attention is fixed on the nearby statuette of a naked dwarf, dissipated yet vestigially fashionable, rendered in the manner of the African sculpture which was then at the height of its vogue. The plate has a broader humor than Barbier usually allows himself. The best known plates of Falbalas et fanfreluches are those depicting the seven deadly sins in the volume for 1925. Here one finds a great theme of western iconographical tradition made at home in Barbier's special world. "Anger" shows a modish couple quarrelling in a formal garden, "Envy" is displayed by a maid regarding her mistress as [2.12] she steps from a Rolls Royce, and "Gluttony" is etherealized into "Lagourmandise."

Falbalas et fanfreluches was the last of Barbier's books to reflect

Certainly his mind was filled with available images. All his life he had frequented museums, antique shops, and bookstores. He had the history of costume at his finger tips. The two volume catalogue of the sale of his library offers striking testimony to his inexhaustible curiosity and wide-ranging connoisseurship.[23] Most of its 1093 lots are made up of illustrated books, chosen with extraordinary discrimination. The 18th century is well represented. The 19th century is there in abundance, both with regard to books, where Gustave Doré was a special favorite, and albums of lithographs, where Gavarni stands out. As one would expect, there are substantial sections on the dance and on costume. When Barbier applied himself to brief surveys of the history of costume illustration or of the pochoir process, he had no need to go beyond his own shelves to write them.

Most illuminating for the student of Barbier's work, however, are the parts of the catalogue, by far the largest, devoted to 20th century illustrated books and literary first editions. In his introduction Jean Giraudoux speaks warmly of Barbier's quick eye and generous admiration for talent among the workers of his own time. So one finds most of the outstanding illustrated books of the Belle Époque, with particular attention being paid to Maurice Denis, Auguste Lepère, Louis Legrand, and Luc-Olivier Merson. Across the Channel Aubrey Beardsley, Charles Ricketts, and Lucien Pissarro are fully represented. Among Barbier's favored illustrators of the 1920s were such early associates as Guy Arnoux, Pierre Brissaud, Charles Martin, and André-Édouard Marty, as well as Alexeieff, Chas Laborde, Daragnès, Pierre Falké, Laboureur, and Schmied. The literary first editions include substantial runs of Gide, Giraudoux, Louÿs, Henri de Régnier, and Valéry.

Throughout, the books are in collectors' condition. Indeed, Barbier's copies of those in which he himself was concerned are often in decorated

Of course Barbier drew on these extensive materials as an artist rather than as a scholar. Carteret argued that his retrospective designs appealed to "a public fond of reconstructions which captured the tone of fashion in different epochs."[24] Yet it seems absurd to regard plates such as those in Falbalas et fanfreluches with headings like "Switzerland, 18th century" or "Antilles, 19th century" as so many contributions to the understanding of past modes of dress. The artist used his time-travelling as a means of confining his imagination to particular circumstances which would yield a satisfactory drawing. The resulting compositions belong to Barbier-land rather than to history.

The year 1922 saw the appearance of two books illustrated by Barbier which had their origin before the War. Of all literary texts Les chansons de Bilitis by Pierre Louÿs enjoyed his most persistent devotion. These prose poems, which purported to be translations from the Greek of songs composed by a poetess of Sappho's time, were published in 1894. In 1910 Barbier adorned Lotz-Brissonneau's copy of the 1898 edition with 65 water-colors, 26 of them full page, signed "E.-W. Larry." In a letter to his patron, after affirming his devotion to ancient Greece, he remarked of Louÿs' work: "It is all licentiousness and beauty and I would have wished in my drawings to convey something of the sensuality and color with which he animates these perfect poems."[25] Commissioned by Pierre Corrard to provide illustrations for a major edition of Les chansons de Bilitis,Barbier immediately set about further drawings, but Corrard died in 1914, and his widow finally published the book in an edition of 125 copies in only 1922. A handsome quarto, remarkable for its layout and typography as well as for its illustrations, which were engraved by Schmied and printed in color, it might have vied with Schmied's Le livre de la jungle as an example of the sumptuous realizations which lay within the grasp of post-War bookmakers if it had appeared three years earlier. Certainly it contains Barbier's most varied studies of the female form. [2.13] Two examples must suffice: "Les trois beautés de Mnasidika," in which a nymph tells of the sacrifices she has made to Aphrodite for her lover

Personnages de comédie of 1922 is a still more considerable accomplishment than the edition of Les chansons de Bilitis of the same year. [2.16] Indeed, its 12 large plates, engraved by Schmied and printed in color by Pierre Bouchet, are rivalled in Barbier's work only by those in Le bonheur du jour. Albert Flament's text of 1914 is a diffuse meditation, half-waking and half-dreaming, which takes as its point of departure the great roles of the world theatre. Barbier's vignettes have a general relevance to the theme of acting, but most of his plates, at least one of which dates from 1916, are simply magnificent decorative compositions. Thus [2.17] Phaedra is mentioned by Flament, but not the equally evocative Greek sorceress who receives homage from her creatures in an earlier design. Perhaps Personnages de comédie is best regarded as a demonstration of the cumulative richness which could be achieved by the combined talents of Barbier, Schmied, and Bouchet.

If six years passed before the appearance of Barbier's next major book, this does not mean that he had forsaken illustration in the interval. His practice was to spend years over each project, returning to it from time to time as the spirit moved him. It is true, however, that between the end of the War and the later 1920s much of his time was claimed by theatrical design. This new career began with Rostand's Casanova, performed at the Bouffes-Parisiens in 1919. Barbier's costumes and scenery are recorded in an album of 1921 called Panorama dramatique: Casanova,illustrated with 24 pochoir plates executed by Jacomet. Other successes followed, and for a time he was the most sought-after costume designer in Paris, recognized as the theatrical artist who better than any other had captured the mood of the age. His work through 1922 may be seen in an elegant album called Vingt-cinq costumes pour le théâtre which appeared in 1927. Edmond Jaloux's discerning introduction suggests how Barbier helped to transform the mundane atmosphere of the pre-War Paris theatre, with its bourgeois settings for well-made plays, into "a kind of many-colored dream" (p. 14). Jaloux found that Barbier's extraordinary costumes—which were more than costumes, indeed, since they seemed to

His personnages are from no time and no country. . . . Their costumes are the most extravagant and fantastic in the world. . . . It is a taste not exactly English, or German, or French, or Turkish, or Spanish, or Tartar, . . . though it includes a little of what every country has that is most graceful and most characteristic. (pp. 14-15)

[2.18] Typical of Barbier's creations are Don Juan in Rostand's La dernière [2.19] nuit de Don Juan and Paulette Duval in the sumptuous ballet Le tapis persan. From the theatre Barbier proceeded to the music hall, the vastly larger resources of which enabled him to achieve effects "of unbridled fantasy and opulence" in such works as "Le légende du Nil" and "L'Eventailde diamant" at the Folies Bergères.[27]

The year 1928 saw the appearance of books illustrated by Barbier set in the two periods where his imagination moved most freely, ancient Greece and 18th century France. In Maurice de Guérin's Poèmes en [2.20] prose he returned to mythological themes, specifically to the story of the centaur and the bacchant (p. v), in an elegant volume for which Pierre Bouchet engraved his drawings on wood and saw to their printing in color and Schmied provided the "maquette typographique." Verlaine's Fêtes galantes was a more important undertaking. Some of Barbier's drawings for this collection of poems, including that for the frontispiece, go back to 1920, and a number of others are dated between 1923 and 1925. In their large scale and ornate elaboration, indeed, they bring to mind his plates for Le bonheur du jour. To study them is to be reminded that Verlaine's poems for this volume, the second which he published, are said to have been inspired by his reading of the Goncourts' L'Art au dixhuitièmesiècle with its celebration of the pastoral paintings of Watteau, Boucher, and Fragonard. For the most part Barbier's depictions of the gallant life of the time have an open-air setting. Perhaps the characters [2.21] Barbier assembles in his plate for "Clair de lune" (p. 3), the first poem in the collection, best epitomize the "chosen landscapes" by which he tried to realize Verlaine's dream-like visions. Barbier's designs are full of [2.22] fantastic touches without warrant in the poet's text. In "Les ingénus" (p. 27), for example, the lovers amusing themselves in a park on an autumn evening do not include the fawn receiving the attentions of the lady by the pool. Fêtes galantes is the most frequently encountered of Barbier's major books. Strictly speaking, indeed, it has to be regarded as a demi-luxe edition since Piazza published 1200 copies. Some 225, however,

Marcel Schwob's Vies imaginaires of 1929 might have been written on purpose for Barbier to illustrate, so directly was it calculated to appeal to his temperament and his way of proceeding. The author selected from history 22 figures whose personalities and stories he found piquant, most of dubious, some of criminal, reputation. Among them were Petronius, Paolo Uccello, Captain Kidd, and Burke and Hare. Barbier's drawings, engraved on wood and printed in color by Bouchet, show how taken he was by Schwob's subjects. They include headpieces, initial letters, and tailpieces, as well as plates devoted to the 12 figures who interested him most. While preserving the settings and costumes of their times, he makes [2.23] them all inhabitants of an elegant, ambiguous country in which conventional expectations are invariably disappointed. In a frontispiece the muse of intimate history gazes into a globe and dictates what she sees to a cupid. Passing by the heretical brother Dolcino, who can be taken as a [2.24] mocking commentary on the saints depicted by Maurice Denis, Clodia [2.25] accompanying her brother to a Roman brothel (p. 44) and Pocahontas meeting Captain John Smith (p. 126) may be singled out among the book's Art Deco tableaux.

This concludes the roll-call of Barbier's substantial books, except for Les liaisons dangereuses, reserved for discussion in another context, but something must also be said of the demi-luxe volumes which he illustrated. The most interesting of these is René Boylesve's Le carrosse aux deux lézards verts of 1921. Here one admires not so much the eight plates as the scores of smaller designs with which the text is decorated, thus following the pattern for demi-luxe books recently established by Robert Bonfils. His vignettes provide a sprightly commentary on this 18th century fairy tale, enhanced as they are by Saudé's brilliant demon- [2.26] stration of the possibilities of pochoir. The beginning of chapter 4 provides a typical opening.

Four of the five titles which Barbier undertook between 1924 and 1931 for Mornay's series, Les Beaux Livres, are tales by Henri de Régnier, also with 18th century settings. They hardly require comment, since their sparse pochoir illustrations are overshadowed by his drawings for Les [2.27] liaisons dangereuses. More attractive is Gautier's Le roman de la momieof 1929, thanks in large part to the harmonious engravings printed in color by which Gasperini rendered the artist's designs. Barbier seems to have welcomed the opportunity offered by Gautier's Egyptian setting to rival the middle eastern subjects which preoccupied Schmied at this time.

My account of Barbier the book-artist has emphasized the extent to

Parle des mythes dans l'abstrait,

Barbier les capte d'un pur trait,

Vainqueur du néant par l'image![28]

In seizing this image, no labor was too arduous for him. Indeed, Clément-Janin relates how "he delighted in minute details, hardly to be suspected, which yet had their place in the impression made by the whole. `Why,' asked one of his students, `do you put into your water colors those touches which no one sees?'—`But I,' he answered, `I know that they are there' " (p. 136).

To this search for perfection Barbier brought formidable resources of knowledge as well as talent. Yet no artist was ever less of a pedant. In describing a visit to his atelier, Vaudoyer found a symbol for the relation between his learning and his art. Three of its walls were given over to precious objects of all sorts, Barbier's choice among the creations with which earlier craftsmen had served beauty, and the world of art had celebrated luxury and fantasy. The fourth wall was curtained beneath a skylight. Barbier sat facing it, behind a table holding his brushes and paints," forgetful of the concerns of sedentary life. He no longer sees anything in front of him but his own dreams. Before catching them in flight for perpetuation on Whatman or Canson, for a moment he watches them pass on the great screen of the sky among clouds and sunbeams" (p. 48).

Nor did his labors end with his drawings. He saw each of his books through to its completion, supervising all aspects of its planning and production. Clément-Janin wrote near the end of Barbier's career:

He is the publisher's constant collaborator; . . . he supervises the composition of colored inks, as well as their application on the page. The title pages . . .are always designed by him, at least for the éditions de grand luxe. . . .

But his participation doesn't end there. He also directs his interpreters, the wood engravers. His water-colors, executed with precious skill, must not lose this quality under the graver of an unskillful craftsman. Printing also demands particular care. To render these sumptuous materials, these velvety blacks, these deep blues or reds, these delicate pinks, the bloom of flesh tints, these insensible gradations of tone, everything between gold and platinum,

What this absorption in the details of production added to Barbier's work can be shown from his last major book, Les liaisons dangereuses.That he would turn his attention to Choderlos de Laclos' great novel of sexual intrigue was inevitable. Eighteenth century France, particularly during the decades before the Revolution, had become his favorite country of the mind. In this instance, moreover, he was prepared to illustrate his text rather than to use it as a point of departure for decorative compositions. His imaginative involvement with the novel's subject can be traced back at least to 1920, when he contributed to La guirlande des moiscertain "fragments found in the papers of the late Marquis de la Caille" (4: 33-45). Entitled "L'Amour de plaisir ou le plaisir d'amour," these are the mordant reflections of a cynical libertine who might have been Laclos' Vicomte de Valmont. In 1929 and 1930 he made 20 large drawings for the novel, as well as a number of smaller drawings for vignettes and decorations. Though Barbier did not neglect the opportunities for decorative treatment of setting and costume which the novel provided, he for once submitted willingly to the straight-jacket of the illustrator, maintaining the major characters in keeping and presenting all the big scenes in its intricate plot, even when, as in the duel between Valmont and the Chevalier Danceny (2: 192), they were well outside his usual range. The resulting drawings were as comprehensive and effective as any conceived for the novel since Charles Monnet and Mlle. Gérard collaborated in their classic illustrations of 1796.

Unfortunately, there was the usual delay between the completion of Barbier's designs and their appearance in book form. Barbier died in 1932, and when they were published two years later, the absence of his guiding hand was everywhere apparent. The publisher, Le Vasseur, declared that the dead artist had put into the book "the best of his talent, of his personality: all his art, all his knowledge."[29] Nonetheless, he allowed himself to print 720 copies, an edition so large as to necessitate the use of mechanical process to reproduce the artist's designs, the colors apparently being added by pochoir. They were also reduced in size. The damage can be assessed by a comparison of the original drawings[30] with [2.28] their reproductions. Consider the vignette facing the title page of volume [2.29] 2. Barbier's line is so distorted as to impair its firmness. The harmony of his color scheme is disturbed; there is no hint of red in the mermaid's hair, and her scales are blue instead of green. Even more injurious are the

Barbier was a supreme decorative designer, whose art centered on the human figure, displayed in a thousand different settings and costumes. He had the faculty, as Valéry wrote, of embodying myth through images in such a way that workers in mere words could only look on in awe. These images are beautiful, but their beauty is of an enigmatic kind. In Barbier's library were 12 volumes illustrated by Edmund Dulac and 10 by Arthur Rackham between 1906 and 1918 (lots 223-224). Yet, despite their common preoccupation with color, to describe Barbier as a Rackham, even if not for the nursery, would be utterly misleading. In fact, he embodied the temper of the 1920s in much the same way that Beardsley did that of the 1890s. He was drawn to erotic themes, particularly of an ambiguous nature, and his sensibility enabled him to present them, through both male and female figures, in a powerful and haunting way. These figures make an impression beyond their sensual appeal. In an essay on Casanova's memoirs Barbier described "the soul of Venice" in the great adventurer's time as "at once avid and exhausted, raging and desperate, and, under the rouge already putrefying."[31] The equivocal nature of the sophisticated society of Barbier's time is similarly conveyed by his compositions. Indeed, this is perhaps his truly original note.

No account of the French Art Deco book can afford to pass by pochoirillustrations, which surely constitute the field of liveliest activity among today's Art Deco book collectors. Consideration of this process may appropriately be associated with George Barbier, even though the drawings for most of his major books were rendered by wood engravings printed in color. Pochoir was used in much of his early work, as well as for Fêtes galantes and Les liaisons dangereuses, and in the 1920s such former colleagues of his on the Gazette du bon ton as Arnoux, Brissaud, Brunelleschi, Lepape, Martin, and André-Édouard Marty were among the illustrators with whom that magazine was most prominently identified. Moreover, Barbier became a champion of pochoir in its struggle for acceptance among publishers and collectors of livres d'art. In assuming this role, he wrote, he was settling

a debt of gratitude, for my first drawings were reproduced by the master colorist Saudé, with a fidelity which I found astonishing. First prints, like first loves, are the most beautiful of all; the artist then feels, through the rendering of his work, a little of the delight of a young woman, on the eve of her debut in society, who looks in the mirror and finds herself made beautiful. This is a joy which passes quickly.[32]

We may open the topic with Jean Saudé's Traité d'enluminure d'artau pochoir, published during 1925 in an edition of 500 copies. Now itself a major collector's book, it is no mere technical treatise. Instead it is at once a manifesto asserting the claims of pochoir and a demonstration through its own illustrations of the appropriateness of pochoir for the livre d'art. Saudé's text is prefaced by tributes from several admirers. Particularly to our purpose are the remarks of Édouard Bénédictus, several of whose design albums had been colored by Saudé. He claimed that it was Saudé's accomplishment "to make known certain new artistic forms, such as the highly sensitive works of modern artists, which without his methods, might have remained unfamiliar to us because they could not be reproduced, or indeed might have come to us radically changed in photomechanical copies" (p. 2). He also emphasized Saudé's extensive range. In his hands pochoir "encompasses all forms of art, old and new, in all areas of artistic and industrial activity, prints, miniatures, documentary works, catalogues, postcards, wall decorations, fabrics, and so many other things" (p. 4).

In his own part of the book Saudé first concerns himself with the history of coloring by stencil, a subject which had become familiar to him during 30 years of craftsmanship, tracing it from the Middle Ages to the present. He then offers his social credo: that the decorative arts combined with technology can promote humanity's well-being by bringing beauty within the grasp of the multitude (pp. 26-27). Finally, he describes in detail, with due attention to the refinements which a master of the craft can introduce, how pochoir work is accomplished (pp. 35-64).

First, the water color to be reproduced is photographed. After the colors in the original are analyzed, proofs of the photograph are lightly printed in a neutral tone, and each color is transferred to its individual proof. Cut-outs from very thin sheets of zinc or copper are made from these proofs. They are placed successively on the page to be colored, and the color is added through the cut-out by brush or other means. Saudé's example of this crucial step is "Les roses" by Mme. Beauzée-Reynaud, in reproducing which he employed 32 pochoirs. He shows the resulting plate as it appeared after 5, after 10, after 25, and after 32 of these stencils. For more complex water colors the number required could be much

The year 1925 was a turning point in the fortunes of pochoir as a process for illustrating livres d'art. Taken together, Saudé's Traité and his display at the great Art Deco exhibition caused influential voices to be raised in its behalf. The writer of the section on books in the Rapportgénéral of the exhibition was impressed not only by the "rich polychromes" which he showed, but also by the "limited stock of tools" which had produced them.

Operations which demand, in addition to the precise analysis of colors in the subject, experience, skill, and taste, make this mode of illustration an artist's calling as well as a mere technique of illustration. . . . Coloring by pochoir,as is demonstrated in the works which Saudé exhibits, lends itself to the artist's most subtle requirements. It is the natural complement to the livre deluxe in limited editions.

(7: 49-50)In an article for The Studio of 1926, which for the most part was a summary of Saudé's treatise, Marcel Valotaire stressed "the important place which [pochoir] has come to occupy in the illustration of the French artistic book" and remarked that "This victory over the conservatism of the bibliophiles as to processes of reproduction is fully justified by the qualities themselves of the plates thus obtained."[33] Barbier was equally decisive in an article entitled "Pochoirs" which appeared in 1928: "Certain critics profess to disdain pochoir as unworthy of the livre de luxe.For my part I think unjustified this exclusion of a technique which maintains a work of art in all its freshness, avoiding the often rather chilling transposition resulting from mechanical processes" (p. 163).

Pochoir, or enluminure as Saudé preferred to call it, was practiced by other notable craftsmen, three of whom should be specifically mentioned. André Marty (not to be confused with the illustrator, André-Édouard Marty, who often employed pochoir for his designs) had been responsible for its renaissance at the turn of the century. He was succeeded by Daniel Jacomet, the master of facsimile reproduction of drawings by artists from Fragonard to Toulouse-Lautrec. Even the great lacquerist Jean Dunand attempted illumination, as we shall see in connection with Schmied. At the height of its employment, indeed, pochoir coloring became a considerable

Nothing is prettier to see [wrote Barbier] than the atelier of a colorist, with its great skylights through which the light surges bathing the workers, many of whom are young women, busy with their graceful task. On the tables, pots of colors sparkle like bouquets, nimble hands fly from sheet to sheet, passing a brush moist with color over the stencils. What an engaging sight! What blissful work [it is] which calls for these quick hands, this smiling dexterity, this good taste so characteristic of [our] little Parisians.

(p. 162)Though Valotaire celebrated the victory of pochoir over "the conservatism of the bibliophiles" and claimed that artists were turning to it from wood engravings or etchings printed in color, there remained a hard core of opposition to its use in the livre d'art. This may be exampled from the writings of three of the leading authorities of the time: Hesse, Clément-Janin, and Carteret, who typically made their distaste known by implication or omission rather than direct statement. This is true, for example, of Hesse's Le livre d'art du XIXe siècle à nos jours, in which books illustrated by pochoir are not discussed on the ground that they belong to the commercial rather than the bibliophilic realm.[34] In his later Le livre d'art d'après-guerre he followed the same rule. Encountering Maeterlinck's L'Oiseau bleu, a book with pochoir illustrations by Lepape, he pulls himself up short: "but here we leave the livre d'art for the colored image" (p. 86). Clément-Janin ignores pochoir in his Essaisur la bibliophilie contemporaine de 1900 à 1928, even in chapter 11 devoted specifically to colored illustration. Carteret included few pochoirbooks in his detailed listing of outstanding titles in volume 3 of Le trésordu bibliophile. His judgment on the technique is implied when he writes that Barbier's work arouses enthusiasm "above all when the colors are rendered by engravings on wood by masters like Schmied, the Beltrand brothers or by Pierre Bouchet, capable of attaining perfection by the closest attention to the minutiae of the printing" (3: 178).

The employment of pochoir in the livre d'art reached its apogee in the later 1920s, and it continued to be used with some frequency during the 1930s. When Le portique conducted a survey of the condition and prospects of the livre d'art after the second World War, the editors' conclusion was that, though the process had "already won the freedom of the city, being admitted under certain conditions," some influential publishers were inclined to insist on these conditions.[35] An account of pochoirin 1975, describing the ateliers in which it was still practiced, tells how

Particularly during the last ten years collectors have become increasingly interested in examples of pochoir coloring in all of its varied applications. There is also a lively demand for pochoir fashion plates, with their fresh and sparkling colors, among those seeking decorative prints to adorn their walls. In comparison with these markets, that offered by amateurs of livres d'art may be minor, but it is not inconsequential. Long since deflected from Barbier and Schmied, whose books illustrated with wood engravings printed in color have soared beyond their means, they can still pursue other notable colorists of the 1920s whose work was rendered in pochoir. Often published in demi-luxe editions of considerable size, these books have remained available as well as relatively inexpensive.

The most attractive of such productions are the volumes of decorative illustrators like Arnoux, Brissaud, Brunelleschi, Lepape, Martin, and A.-É. Marty, who had collaborated before the War in La gazette du bonton, and of later recruits who worked in a similar style like Pierre Falkéand Edy Legrand. Since each had a substantial and distinctive career, they cannot be considered one by one. It must suffice to offer a few examples from their productions, chosen to reveal the variety of subjects which they attempted, the gamut of effects which coloring by pochoircould achieve, and the wide range of markets at which the resulting volumes were aimed, from popular works to livres de grande luxe.

One of the handsomest of all pochoir books is Edy Legrand's Voyages et glorieuses découvertes des grands navigateurs et explorateurs françaisof 1921. This slim folio, which is fairly ablaze with illustrations on every page, bears no notice of limitation and was evidently published in considerable numbers. For that reason it was not regarded even as an édition de demi-luxe. Yet its bold designs and brilliant coloring make the free and unstudied handling of its pochoir work seem entirely fitting, remote as it is from Saudé's ideal. A representative page shows Jacques Cartier [2.31] relating his discoveries to Francis I. Legrand's most ambitious composition, a double page opening, depicts Lasalle taking possession of Louisiana, with the Indian tribes making their submissions. Much more restrained is Guy Arnoux's Les caractères of 1922, an album of 500 copies

In the 1920s pochoir was often disdained by collectors swayed by accepted bibliophilic orthodoxy. In consequence publishers of livres d'arttended to prefer wood engravings or even etchings printed in color, particularly for éditions de grand luxe. This a priori prejudice has long since been dissipated, just as there is now general agreement that pochoirillustration is far more appealing than any form of mechanical process, with which it used to be lumped. But the question remains: what are the merits of pochoir as compared with wood engravings printed in color? We know that Barbier used the latter for most of his important books, Schmied for nearly all of his. One of the interests in the review of Schmied's work, the subject of the next lecture, will be the resources that he commanded in comparison to those available to the users of pochoir.

George Barbier (Paris, 1929), volume 10 in the collection "Les artistes du livre," published by Henri Babou.

In the other chief essay on the artist, "George Barbier, costumier des muses," Plaisir de bibliophile, 19-20 (1929), 134-147, Clément-Janin is evidently mistaken in placing his coming to Paris in 1911, though both writers had information from Barbier himself.

Catalogue de la bibliothèque de feu M. George Barbier (2 vols.; Paris, 1932-33). These are auction catalogues for sales at the Hôtel Drouot on 13-15 December 1932 and 10-13 March 1933.

Le trésor du bibliophile: livres illustrés modernes, 1875 à 1945 (5 vols.; Paris, 1946-48),3: 178.

See the remarkable catalogue Livres illustrés 1900-1930 from Slatkine Beaux Livres (Geneva, 1980), item 43.

Catalogue de la bibliothèque de feu M. George Barbier, lot 420. The quatrain was written by Valéry on a blank leaf in Barbier's copy of Maurice de Guérin's Poèmes en proseof 1928.

M. Fleurent, "Où va la bibliophilie? une enquête du `Portique,' " Le portique, 2 (Summer 1945), 124.

3. François-Louis Schmied

The work of few book-artists has undergone such reversals of fortune as that of François-Louis Schmied. A Swiss who migrated to Paris as a young man, he had first to overcome the distrust with which the French tend to regard foreigners working among them. During the World War he enlisted in the army as a volunteer, where the grave injuries which he sustained caused a French critic to concede that he had "earned the right to be called one of us."[37] Even so success came to him only as he approached 50. A "decorator-born," as his friend Dr. Mardrus called him,[38] he then benefitted more than any other book-artist from the boom in livres d'art. Not only did he attract wealthy and distinguished patrons, but collectors generally joined with them in raising his numerous productions to the peak of contemporary esteem. Yet a residue of bitterness

Since Schmied did not achieve fame until the early 1920s, relatively little is known of his early life.[39] The Genevan family into which he was born in 1873 intended him for a career in business, and it was only through application to artistic studies outside working hours that he found his first patron, the painter Barthélemy Menn. In 1890 his parents allowed Schmied to devote himself to original wood engraving under the tutelage of the Swiss master, Alfred Martin, who also trained Carlègle. From Martin he learned much about design as well, and in the Bibliothèque Municipale of Geneva he had made a profound study of typography and the layout of the page before he departed for Paris in 1895.

Though he was employed in that city primarily as a reproductive engraver, he continued to draw and to experiment with original engraving printed in color. His innovations during the first decade of the new century included the printing of engravings in the manner of paintings with no separation of the colors by black lines and the extensive use of gold and silver in their backgrounds. Among those impressed by his work was Auguste Lepère, who had raised color printing to its seeming apogee in his editions of À rebours in 1903 and L'Éloge de la folie in 1906. "You are going to create truly rich engraving [la gravure riche]," he told Schmied. "I had a presentiment, while printing À rebours, of what infinite resources might offer themselves to the painter-artist who would have the courage to assimilate the craft of the printer-engraver."[40]

It was a good many years before Schmied bore out this prediction. In 1911 one of the leading societies of bibliophiles, Le Livre Contemporain, commissioned a luxurious edition of Kipling's The Jungle Book and The Second Jungle Book. The animal painter Paul Jouve was selected as its illustrator, and Jouve turned to Schmied for engravings printed in color of his designs.[41] As their collaboration developed, Schmied had a hand in drawing the illustrations as well as in their engraving. Both artists went off to the War, Jouve being mobilized, and Schmied enlisting in the foreign legion. Severely wounded in action at Capy on the Somme,

As the first major livre d'art to appear after the War, Le livre de la jungle is a landmark book. Its layout and typography, though sober and dignified, are undistinguished, and its more than 400 large quarto pages seem under-illustrated when compared with Schmied's later profusion in this respect. Nonetheless, Jouve's drawings, as completed and engraved on wood by Schmied and printed in color on hand presses by Pierre Bouchet, are sumptuous indeed. It cannot be determined exactly what part Schmied had in the drawing of the illustrations. Hesse states that Jouve "furnished only 15 finished drawings out of 90. For the rest he provided only preliminary studies" (p. 178). The book in fact has 122 designs: 17 plates, 15 initial letters, and the rest vignettes in the text. No doubt the initial letters, which are often abstract, were largely Schmied's work. It would seem that he must also have been responsible for bringing to completion a number of Jouve's sketches.