| | ||

1. The Livre d'Art OF THE 1920S

I should begin by explaining my choice of topic. Three years ago I wrote a two-volume survey called The Art of the French Illustrated Book, 1700 to 1914, which was published in conjunction with an exhibition at the Pierpont Morgan Library drawn largely from my own collection. In my Introduction I noted that the terminal date had prevented me from dealing with my Art Deco books, which I hoped one day to make "the basis for a small sequel to this history" (1: xxxi). These lectures form the promised sequel.

Once I set to work, however, I discovered the drastic inadequacy of what I had collected. Now, notable Art Deco books, especially in decorated bindings of the period, have never been readily available for examination even in France. Since the dispersal of the late Francis Kettaneh's collection, which provided the backbone of the Grolier Club's exhibition of French Art Deco illustration in 1968, they are still less accessible in the United States. But I persisted, and with the assistance of various institutions and private collectors, I have managed to cover the field. My particular indebtedness is to the Spencer Collection in the New York Public Library, the Frank Altschul Collection at Yale, the Morgan Gunst Collection at Stanford, and the remarkable assemblage of books illustrated by the pochoir process still in the process of formation by Charles Rahn Fry of New York City. These holdings will allow me to display and comment on much unique material in the form of drawings, proofs, and especially bindings.

I can at least claim that my subject is a timely one. The rediscovery of Art Deco in general, which has been proceeding with increasing fervor

These developments have had their impact on rare book sales generally. Parisian dealers, while setting their prices as usual at a point just below that at which no customer would consider buying, remain unexcited. Having dealt continuously with illustrated books of the 1920s since these volumes began to appear, they have their considered views regarding such wares. Moreover, they know how extensive the reserve supply of them must be. Among dealers elsewhere in Europe and in the United States, however, there has been a disposition to move these books up to the level established at Art Deco auctions.

This practice would be legitimate enough, given the importance of Art Deco in the evolution of styles, if the material so offered in fact represented it. But most French illustrated books of the 1920s were largely untouched by Art Deco, just as many decorated morocco bindings of the period were executed by craftsmen who continued to work in an earlier tradition. Moreover, a considerable proportion of the abundant productions of the time, including some of the most elaborate and pretentious, were ill-conceived and poorly carried out. Deprived of the sheltering cloak of Art Deco, most illustrated books of the 1920s require to be appraised individually, with drastically lowered expectations. In view of these conditions, a survey of the field, however tentative and incomplete, would appear to have some practical usefulness.

My perspective is that of a collector who for many years has endeavored to find out as much as he could about French illustrated books of the last three centuries. Concerning the volumes of the 1920s the sources of information for the most part are contemporary with the period itself, since these books haven't as yet attracted much attention from modern

I propose to limit my account of the Art Deco book in France to the 1920s, or at least to the years 1919 to 1930. This decade was its heyday, the years which saw the appearance of most of the best work of its representative masters. Moreover, the period saw the reemergence of the livre d'art, as the fine illustrated book for collectors was then called, on a quite unprecedented scale. This crescendo of production led to notable achievements as well as deplorable follies and concluded with a catastrophic debacle. I shall thus be dealing with a self-contained episode in the history of book collecting, an episode which embodies some of the elements of high drama.

The world of fine illustrated books before the first World War was flourishing but limited. Its requirements were met by perhaps 15 publishers, and its clientele hardly extended beyond a few hundred collectors, most of them well-to-do men of affairs. Prominent on the scene were the Societies of Bibliophiles, under whose aegis were published many of the best books of the time in editions of from 75 to 150 copies. A relatively small number of illustrators, printers, and binders served the needs of what in the perspective of later developments came to seem almost a closed circle. Nonetheless, superb books appeared, though it is true that a few of the most outstanding were published by outsiders such as Ambroise Vollard.[1]

The conditions imposed by the first World War laid a virtual embargo on the publication of livres d'art. The apparatus that produced them fell apart, the collectors who acquired them had other preoccupations,

The hectic aspects of Paris during the 1920s which caused the decade to be called les années folles will figure in my chronicle chiefly as they are reflected in the work of George Barbier. Yet the temper of the age does much to explain the conditions which governed the publication of livres d'art. If rampant prosperity combined with a post-War release from inhibitions to encourage the pursuit of pleasure, these factors stimulated as well an eager desire for luxurious possessions, among them fine books. Nor did bourgeois prudence provide an effective check, since the soundness of the franc was an open question. One observer estimated, indeed, that the public for livres d'art grew ten-fold after the War.[4] Clément-Janin discerned three kinds of enthusiasts in this "prodigious development" of book collecting: (1) major collectors prepared to spend 1000 to 5000 francs on a livre d'art limited to 150 copies or fewer, (2) middle-range collectors who would pay up to 500 francs for a book limited to not more than 500 or 600 copies, and (3) lesser collectors able to spend 40 to 100 francs for mass-produced illustrated books in editions of not more than 3000 copies (2: 152-153). Not only were these new collectors numerous and diverse, for the most part they were also undemanding. As long as the mandatory features of the livre d'art were present—special paper, illustrations, and a limited edition—they were easily satisfied.

Attracted by this large and ready market, publishers multiplied apace, and so did the books they published. Among those protesting against this incontinence was the art critic Jacques Deville, who permitted himself the following tirade:

With the field of book illustration so vastly enlarged, many new artists were drawn into it. These recruits were of uneven quality, as Raymond Hesse demonstrates from the example of books with original wood engravings, for some years after the War the kind of illustration most in favor with collectors. Though illustrators like Louis Jou, Carlègle, and Hermann-Paul produced work of distinction, wood engravings, which can be printed conjointly with text, were also the least expensive adornment that was acceptable in collectors' books, and when publishers avid for profit employed journeymen artists, untrained in the craft, the results were usually lamentable (pp. 150-151).

In his book of 1927 on 19th and 20th century livres d'art, Hesse drew a devastating picture of the contemporary publishing scene. A year later, when he wrote a volume entirely concerned with the post-War book, he had been led by further study to this more balanced comparison of the pre-War and post-War book:

The two periods differ as an English garden does from a virgin forest. In the one: order, method, reason; in the other nature, color, noise, confusion. You walk through the first in entire safety—nothing unexpected but no monsters or wild beasts; in the second, besides unfamiliar and splendid landscapes, you run the constant risk of falling into some mudhole.[6]

One final element in the collecting scene of the 1920s needs to be considered, the extent to which it was affected by speculation. Like other valuable objects, livres d'art could be seen as a hedge against inflation. As in our own time, a collector who bought on publication a book which

Yet this is not the whole story. Even if the possessors of livres d'artwere not conscious speculators, they went on collecting in part because they had more faith in their books than in a declining franc. This judgment seemed to be confirmed in 1928 when the franc was devalued by 4/5ths (from 19.3 to 3.92 cents) yet the value of livres d'art did not diminish. So it was that, despite uncertainties and reverses, the growth of book production and collecting continued unabated. As late as 1928 Clément-Janin expressed "an absolute faith in the persistence of the movement which has carried book collecting to its current flourishing state." To his mind its soundness had been demonstrated during the great monetary crisis wherein was achieved "that profound transformation, that union of the aesthetic and the financial, . . . [which] makes contemporary book collecting durable" (2: 197, 199).

By the winter of 1930-31, before these words were published, the world-wide depression heralded by the Wall Street crash of 1929 had struck France as well. In the first issue of Le bibliophile for February 1931, Marcel Valotaire wrote despairingly of "this crisis of the livre d'art,the very idea of which weighs heavily on the mind as much of collectors as of printers, publishers, and book-sellers" (p. 31). It had been discovered that in these desperate times the world of rare books was doubly vulnerable. If automobiles ceased to sell, it was because the market was saturated, not because the product was unsatisfactory. The years since The War, however, had seen an absurd multiplication of alleged livres d'art,the work of untrained publishers, designers, and illustrators. While money was plentiful, undiscriminating collectors had freely bought these regrettable productions. But now the book trade was faced with a comprehensive failure of confidence, with an accompanying "disgust, disdain, repudiation by purchasers in the face of the poor, or at least doubtful

EN ÉCOUTANT SATIE

1920

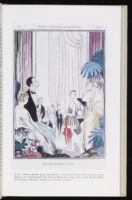

MODES ET MANIÈRES D'AUJOURD'HUI

Pl. XI

PLATE 1. Robert Bonfils, plate from Modes et manières d'aujourd'hui, 9e anné, 1920,[1922] (1.18). Reproduced from Charles Rahn Fry's copy, now in the Charles Rahn Fry Pochoir Collection, Princeton University Library.

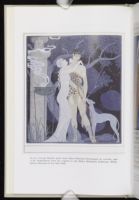

PLATE 2. George Barbier, plate from Albert Flament's Personnages de comédie, 1922 (2.16). Reproduced from the original in the Elisha Whittelsey Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

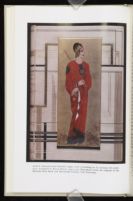

PLATE 3. François-Louis Schmied, text and vignette from Histoire de la princesse Boudour, translated by J.-C. Mardrus, 1926 (3.24). Reproduced from the original in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

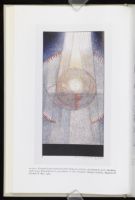

PLATE 4. François-Louis Schmied, plate from La création, translated by J.-C. Mardrus, 1928 (3.30). Reproduced by permission of The Pierpont Morgan Library, Bequest of Gordon N. Ray, 1987.

PLATE 5. Jean-Émile Laboureur, plate from Jean Valmy-Baysse's Tableau des grands magasins, 1925 (4.27). Reproduced by permission of The Pierpont Morgan Library, Bequest of Gordon N. Ray, 1987.

PLATE 6. Pierre Begrain, lower doublure in his album of maquettes, 1929 (5.26). Reproduced by permission from the original in the Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

PLATE 7. Rose Adler, upper cover and spine of binding (1931) on Tristan Bernard's Tableau de la boxe, 1922 (5.37). Reproduced by permission from the original in the Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

PLATE 8. François-Louis Schmied, upper cover of binding on Le cantique des cantiques,translated by Ernest Renan, 1925 (5.45). Reproduced from the original in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

The history just rehearsed makes it evident that any survey of the livres d'art of the 1920s must begin with the question: what proportion of these hundreds of titles (well over a thousand, indeed, if demi-luxevolumes are included) deserves attention today? The answer is, a considerable number, for if the period produced many bad books, it also produced many good ones. At the risk of seeming arbitrary, I propose several categories of worthy survivors.

Pride of place must be accorded to livres de peintre, though in fact the decade saw the appearance chiefly of lesser works of this kind. Only in 1929 and 1930 did the splendid series of major books with original graphics by great painters, the glory of 20th century French book production, really get under way. Charles-Louis Philippe's Bubu de Montparnassewith etchings by Dunoyer de Segonzac was published in the former year, Apollinaire's Calligrammes with lithographs by de Chirico and Eugène Montfort's La belle enfant with etchings by Dufy in the latter.[9] It should be noted that collectors in general were hardly more welcoming to the livre de peintre in the 1920s than they had been before the War. The set of their minds on this topic is exampled in some remarks of Marcel Valotaire, then one of the most knowledgeable and influential of writers on the livre d'art. He wrote of the designs of Laboureur that they are

decorative in their drawing, decorative in their rendering. They are not painter's engravings—an abomination in a book!—, they are the engravings of a graphic artist, established with that solid balance which is the most substantial tie between image and type-page: in a word they are perfect illustrations.[10]

Then there were the established illustrators who resumed their careers after the War. The most distinguished was Maurice Denis, who

Chahine and Jouas also played important roles in the revival of etching. Notable among the colleagues who joined them in displaying the scenery, the architecture, and to a lesser extent the people of France, sometimes working alone, sometimes banded together in the publications of the Société de Saint Eloi, were Auguste Brouet, P.-A. Bouroux, André Dauchez, Pierre Gusman, and towards the end of the decade, Albert Decaris.

Original wood engraving was even more central than etching to the livre d'art, not only in the illustrations of such men as Carlègle and Hermann-Paul, but also in the more comprehensive contributions of three artist-craftsmen who had been trained as wood engravers, François Louis Schmied, Louis Jou, and Jean-Gabriel Daragnès. The three latter were the leading architectes du livre of the time, that is to say workers capable by themselves of creating all the components of a livre d'art.

As colored illustrations came gradually to predominate over those in black and white in the middle and later 1920s, the ascendancy of Schmied and George Barbier was confirmed, the former as the master craftsman of wood engravings printed in color, and the latter as the supreme color stylist, whether his designs were rendered by engraving or by pochoir.Guy Arnoux, Pierre Brissaud, Umberto Brunelleschi, Pierre Falké, Paul Jouve, Georges Lepape, Charles Martin, André-Édouard Marty, and Sylvain Sauvage also stand out for their work in this line.

A number of artists took as their starting point the rejection of the literal detail favored by most pre-War illustrators. Instead they turned to quick, vivid sketches of contemporary life, often accompanying texts by such new novelists as Francis Carco, Jean Giraudoux, Pierre MacOrlan, and Paul Morand. In this group were Gus Bofa, Chas Laborde, Dignimont, and Vertès. Literal realism was equally repugnant to the artists who imposed individual styles of calculated distortion on their subjects. Laboureur was preeminent here, though he had found a formidable rival in Alexeieff by the end of the decade.

Though the best work of all of these artists still deserves the collector's attention, my consideration must be limited to those among them in whose books the Art Deco style is most pronounced. The three lectures following will accordingly center on Barbier, Schmied, and Laboureur, with a final discourse concerned chiefly with Pierre Begrain, the master

Since the incontestable mark of Art Deco in the livre d'art was its emphasis on decoration as opposed to illustration, Schmied's early work, in which the representational element is minimal, offers its purest exemplification. In his later books Schmied supplements decoration with illustration, though he rarely allows the latter to predominate. Abstract decoration was not to Barbier's taste, but throughout his work representational subjects are subordinated to decorative treatment. No doubt his designs are sufficiently striking in conception, but they make their impression above all by their decorative values.

The connection with Art Deco of a third kind of livre d'art, which I shall represent through Laboureur, cannot be made so directly. The book had an important place in the great Exhibition of Decorative and industrial Art held in Paris during 1925. The criterion that dictated the choice of examples to be shown, however, was not so much their decorative qualities as their modernity. Article IV in the general rules of the Exhibition provided that only works of "novel inspiration and real originality"[11] were to be admitted. The French illustrated books displayed had been chosen primarily to demonstrate the variety of techniques and talents of the day. In reviewing these selections the anonymous author of volume 7 of the Rapport général of the Exhibition, that devoted to the book, offers some enlightening comments. While according Schmied more space than any other book-artist, he is at pains to point out at length the surprising ways in which the decorative spirit had affected the vision of other illustrators. "This influence has its part in the tendencies [of the time] towards distortion, in all the liberties that an artist takes with his subject, in the increasingly symbolic character of the design." Moreover, as the pace of modern life grows increasingly rapid, it has to be set down with the briefest of notations. "Accessories are suppressed, the design is reduced to the minimum of lines needed to render it visible at a glance."[12] Laboureur, better than any other book artist of the 1920s, exemplifies these characteristics.

With decorated bookbinding we are back on firmer ground. The work of Pierre Begrain, like that of his numerous imitators, was assertively decorative in nature. Indeed, fine binding during this period was dominated by the growing ascendancy of the Art Deco style after its appeal was demonstrated in the Exhibition of 1925.

With these generalities out of the way, I can turn at last to the books

Perhaps Art Deco is displayed in its purest form in the design portfolios of the 1920s. Their plates were executed by pochoir, that is to say, they were illuminated—to use the word favored by Jean Saudé, the master of pochoir—by water color or gouache through the use of stencils. In conception and layout these portfolios can be traced back to the celebrated Grammar of Ornament by Owen Jones, which appeared in 1856. An important intermediate work was Eugène Grasset's La plante et ses applications ornementales, published in two series in 1896 and 1898. Where Jones had endeavored to classify and illustrate every type of ornament, Grasset turned from man-made inventions to natural forms. His plates, which were drawn by his students, continue Jones's arrangement of several patterns to the page, and they are sometimes varied by the superimposition of objects decorated with these patterns (a vase, a [1.1] pitcher) or shaped in their image (a candlestick, a chair). In the plate shown (first series, plate 66) the object is a mosaic bookbinding.

Grasset's portfolios are a monument to Art Nouveau, exhibiting the various possibilities of flore ornementale. E. A. Séguy's Floréal of 1914 [1.2] also takes its departure from the plant, but as may be seen from plate 17 its designs are adapted with such verve and freedom that the Art Nouveau element has virtually disappeared. Moreover, its pochoir plates, with their subtle gradation of color, exist in a different world from the process reproductions of Grasset's book. A plate (plate 19) from a representative Art Deco portfolio of the 1920s affords a suitable conclusion to this topic. [1.3] Natural objects are still the basis for the drawings in Edouard Bénédictus' Variations of 1923, yet they tend increasingly towards abstract forms, and Saudé's pochoir work, which makes use of a wide gamut of colors including silver, is even richer than that in Floréal. I shall not be returning to

The first landmark in the high fashion tradition which led to Art Deco illustration was Les robes de Paul Poiret of 1908. The great couturier, who had left Worth's in 1904 to establish his own firm, was already famous for the uncorsetted freedom of his novel creations, which women everywhere found distinctive and flattering. In commemoration of his success Poiret commissioned Paul Iribe, one of his many artist friends, to prepare a luxurious album devoted to his work. Iribe focussed [1.4] attention on Poiret's gowns by rendering them in pochoir against rudimentary backgrounds of black and white. There is no pretence on the part of the artist that the figures presented are anything but models.

Three years later appeared a still more sumptuous sequel called Les choses de Paul Poiret vues par Georges Lepape. When Poiret asked Lepape to undertake the volume, the young painter brought him four designs, charming in their simplicity, but also intended to depict models. These are reproduced at the end of the album. After he was shown Poiret's creations, however, he was asked to give his fancy free rein, with varied and engaging results that go far beyond a fashion parade. None of his drawings is like any other in conception, but all are linked in style. Lepape renders even better than Iribe the supple elegance that was Poiret's trademark, yet his most striking design is devoted to another [1.5] house specialty, the turban. As Poiret had predicted, the album made Lepape's reputation.

These two albums had been devoted to a single couturier, if admittedly the best known. La gazette du bon ton, which began to appear in 1912 and continued until 1926, though with an intermission of nearly six years following the outbreak of the War, took the whole world of fashion as its province: Doucet, Paquin, Worth, and the rest, as well as Poiret. At the heart of each issue were 10 pochoir plates, but there were also essays, intended to amuse rather than to inform, on various articles of apparel, on the accoutrements of high life, indeed on choses d'élégance in general. There was a monthly review of theatrical costumes and settings, as well as a column of gossip devoted to fashion and good taste. The text of these pieces was made attractive by pochoir vignettes executed as carefully as the plates. In sum, the magazine represented a way of life, however rarefied and specialized.

Lucien Vogel was already known as the editor of Art et décoration

La gazette du bon ton from its origin was one of the most sought after of fashion publications. Its success, of course, was owing principally to its plates, which are not only records of the dress of the time but also fresh and attractive compositions in themselves. Sometimes they have a [1.6] dramatic element as well. In Lepape's design, "Le jaloux: robe du soir de Paul Poiret" (April 1913), a pretty girl is wooed by an admirer while her elderly protector clenches his fist in rage. The vignettes in the text [1.7] are often true illustrations, as is the case with the scenes from Boris Gudonovwith which Marty illustrates an article on the Ballets Russes of June 1913 (pp. 246-247). Altogether, the style and format of La gazette du bon ton presage what the Art Deco book would become when freed from the fashion straight-jacket.

A second significant fashion publication of the period was the almanac Modes et manières d'aujourd'hui, a slim annual with 12 pochoirplates. Each of its three pre-War volumes had a different illustrator:Lepape in 1912, Martin in 1913, and Barbier in 1914. Their drawings are more ingeniously elaborated than those for La gazette du bon ton. [1.8] Indeed, "L'Ilot" (plate 7) in Barbier's volume may more properly be compared with his depiction of the ballet, "Le spectre de la rose," of the same year, so little is his focus on the bathing dress displayed and so much on the scene of impending seduction. The essentially literary nature of

The imposing pre-War albums devoted to dance and the theatre were inspired for the most part by the Ballets Russes, whose Parisian triumphs had begun in 1909. George Barbier haunted these performances, to which in 1913 and 1914 he devoted collections of drawings, the first concerned with Nijinsky, the second with Tamara Karsavina. These albums have a prominent place in ballet history, but their strongest interest lies elsewhere. Subordinating the opulence of the ballets' productions, but conveying their strangeness and mystery, he concentrated his attention on the principal dancers. As his fellow spectator and devotee Paul Droutot observed, he showed, not gods in their accustomed mythological roles, but "young men and women raised to divine status by their ravishing beauty. You can feel them live, that is to say, love, desire, leap; they are nothing but muscles, supple exertions, nerves, moments of rest between violent gratifications."[14]

Nijinsky was the particular object of Barbier's admiration. Like Francis de Miomandre, who wrote the introduction to his Dessins sur les danses de Vaslav Nijinsky, Barbier saw him as unique among artists, "of another essence from ourselves." In his 12 pochoir plates he showed Nijinsky to be as much a mime as a dancer, adapting himself even in physical appearance to each new role. So the stalwart Ethiopian slave of [1.9] "Sheherazade" became the elusive boy of "Le spectre de la rose."[15]

Album dédié à Tamar Karsavina is Barbier's early masterpiece. Its cover design pays homage to Beardsley, another master of decorative art, and its 12 pochoir plates depict Karsavina in her principal parts. That their purpose is again to stir the emotion and delight the eye of the [1.10] viewer, not to document the performance, is demonstrated by "Le spectre de la rose," glimpsed at the moment when the phantom lover, of whom the young girl has dreamed after the ball, is about to disappear as the rose drops from her hand.

Even more lavish are two further albums, Les masques et les personnages de la comédie italienne, which was published in 1914, with 12 pochoir plates by Brunelleschi, and Sports et Divertissements, in which the score by Erik Satie and 20 pochoir plates by Charles Martin are dated 1914, though the album seems to have appeared at a later date. In his masked figures from an imaginary commedia dell'arte troupe Brunelle- [1.11] Schi emphasizes costume and setting. As "Arlequin" reveals, they are

Finally, there were a few significant illustrated books in which the Art Deco style already predominates published in 1914 or earlier. Francis Jammes' Clara d'Ellebeuse, illustrated by Robert Bonfils, appeared in 1912; Balzac's Le père Goriot, illustrated by Pierre Brissaud, in 1913;and Le cantique des cantiques and Makéda, reine de Saba, chroniqueéthiopienne, both illustrated by Barbier, in 1914. Bonfils, Barbier, and Scmied also had major books in progress on which they were able to work intermittently during the War. Otherwise nothing significant was to come of the preparations that have been described until the end of the decade.

Indeed, the production of collectors' books of any kind over the next four years was minimal. For the soldier-artist, even one who found inspiration in war-time conditions, only the simplest means were available. Yet Laboureur, for example, worked out his cubist style in makeshift albums of wood engravings like Types de l'armée américaine en France (1918) and Images de l'arrière (1919), where he found satisfaction in glimpses of characters from the A.E.F. and the behind-the-lines activities [1.13] of Allied soldiers. Witness a scene of black dock-workers in the former album. Meanwhile, the publisher Meynial had revived the almanac with the publication on Christmas day 1916 of the first volume of La guirlande des mois. This small book is better described as a war-time keepsake thana publication of high fashion, since soldiers back from the front share [1.14] Barbier's five pochoir plates with elegant ladies. There is even an Art Deco battle scene (p. 40). In its miniature way La guirlande des mois is a livre de luxe, but when Meynial replaced it with Falbalas et Fanfreluchesin 1922, it was not without a deprecatory allusion in the final volume to "the artistic character of a publication produced during the War."[16]

If a World War had been the least propitious of all settings for illustrated books, peace-time, when it came, promised to be the most propitious. For Art Deco books Robert Bonfils was the artist who led the way

After his apprentice years in Paris, Bonfils occupied himself with painting, sculpture, and especially the decorative arts. A friend of those days described him as "a tall young man, naturally affable, restrained in gesture, with a grave and musical voice." He passed his days "looking about him, plucking the flower from everything, with an elegant nonchalance. He did not think it frivolous to paint his reveries on the leaf of a fan."[17] From these casual beginnings he went on to a notable career in the decorative arts which extended to designs for porcelain, clothes, fabrics, even tapestries. But the principal focus of his activities was book illustration and binding design.

A man of broad culture, he fell into the habit of drawing in the margins of his favorite poems and stories, and when he turned to book illustration, he thought of his designs as a continuation of this practice. His first book of importance was Francis Jammes' Clara d'Ellebeuse of 1912. Its success led in 1913 to commissions for Henri de Régnier's Les rencontres de monsieur de Bréot and Gerard de Nerval's Sylvie, the latter from the distinguished publisher François Bernouard, hailed by Raymond Hesse as "one of the inspirers of the great `decorative arts effort of 1925' " (p. 146). The war deferred the appearance of these books until 1919. Verlaine's Fêtes galantes with Bonfils' designs appeared in 1915, and "Lover's" Au moins soyez discret in 1919. Sylvie had engravings printed in three colors; the other four volumes were illustrated by pochoir over wood engravings printed in a single color.

Having selected slight but agreeable texts, often with 18th century settings, Bonfils was under no obligation to individualize the figures in them or to present these figures in scenes of dramatic conflict. Instead he could use their activities as occasions for the sympathetic decoration of his pages. He did this for the most part through vignettes, sometimes serving as simple ornaments, sometimes of ampler proportions. Effortless improvisations in appearance, they represent in fact the nicest calculations

Two albums of the period are of particular interest because they show Bonfils working through plates rather than vignettes and as an inventor rather than a commentator. The seven pochoir plates of Divertissements des princesses qui s'ennuient are perhaps his most ambitious drawings, on a scale and accorded a fullness of treatment unmatched elsewhere in his work as an illustrator. Their subject is the amusements of three young ladies at a country house. In keeping with his epigraph from Mallarmé, "Princesse, nommez-nous berger de vos souris," Bonfils treats them with indulgence, but does not disguise the languor of their luxurious lives. Still, it is the opportunity for piquant yet harmonious Art Deco com- [1.17] positions, such as "La promenade" (plate 1), which chiefly interests him.

The volume allotted to Bonfils in Modes et manières d'aujourd'huiis dated 1920 on the title page, though it did not appear until 1922. Its 12 pochoir plates are more fully developed than is usual with the artist. They have no theme, but their emphasis is rather on manners than on fashion, almost leading one to question Robert Burnand's insistence that "no designer is less documentary than Bonfils."[18] Among the aspects of post-War French life presented are the singing of the "Marseillaise" at a theatre, bargain day in a department store, and a family in mourning which watches a military parade from a balcony. Like the other plates, [1.18] the evening party of "En écoutant Satie" (plate 11) is an exercise in perspective.

After 1928 Bonfils illustrated few books. His time was given over to his students at the École Estienne, where he was Professeur de Composition Décorative, and to the writing of a learned manual on La gravure et le livre, which was published in 1938. One may regret that this book is devoted almost exclusively to technical matters, though the author's predilections emerge when he praises original graphics, with their life and spontaneity, as a quick way "for the artist to fix his emotions" (p. 102). Bonfils is one of the most innovative and delightful of Art Deco illustrators. Appreciation of his slim, elegant quartos is bound to increase.

See Gordon N. Ray, The Art of the French Illustrated Book, 1700 to 1914 (2 vols.; New York and Ithaca, 1982), 2; 372-382, 497-498.

Grappe's introduction to Très beaux livres . . . composant la bibliothèque de M. R. Marty (Paris, 1930), p. ii. This is the auction catalogue for a sale at the Hôtel Drouot on 10 13 February 1930.

On the collapse of the rare book market and its consequences, see also Jean Bruller, "Le livre d'art en France: essai d'un classement rationnel," Arts et métiers graphiques, 26 (15 November 1931), 41-66.

Rapport général de l'exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes, Paris, 1925, 7 (Paris, 1929), 51.

| | ||