In the fall of 1724 Franklin took ship for London where he would be "on the Spot . . . to

chuse the Types & see that everything was good of the kind"[4] for the little printing house which Governor Keith of

Pennsylvania had urged him to set up in Philadelphia and declared himself willing to

underwrite. Within days after his arrival Franklin came to understand the nature of the

governor's promises, that they

were well intentioned but hollow, and to

perceive that he was not to have a shop of his own as he had imagined. Further, except out of

curiosity he was now under no compulsion to search among the English foundries for the type

faces which most pleased him.

Franklin's stay in London, according to the Autobiography, lasted

about eighteenth months, from December 24, 1724, to July 23, 1726. Almost immediately upon

arrival he secured employment at the large printing house of Samuel Palmer in Bartholomew

Close, first as a pressman, and later as a compositor. After staying there about a year, he

joined the even larger house of John Watts near Lincoln Inn Fields, where he continued working

until his return to America. The associations with both great printing establishments, one may

infer, left their considerable mark on Franklin and contributed much to a developing interest

in type founding and design.

Located near Palmer's in Bartholomew Close was the type foundry of Thomas James, at that

time the most important firm of its kind in England. Franklin states that he "had seen type

cast at James's in London" (Memoris, p. 136) and observed the craft

sufficiently to be able later while working for Keimer to contrive moulds, crude makeshift

puncheons, and matrices suitable to supply Keimer's wanted sorts. At both Palmer's and Watts'

Franklin would also have heard of William Caslon, whose new type faces were in time to make

obsolete the James' large stock of earlier English and Dutch fonts. Palmer and Watts each had

recognized Caslon's genius, and commended him on his early letter cutting, and encouraged him

to consider type-founding as a career, Palmer repudiating his stand later when some of his

business associates made clear to him that Caslon's success as a founder might ruin their

trade.[5] Hence, a dozen years

before Franklin was to buy his first Caslon fonts, he must have had pointed out to him, or

have seen for himself, the remarkable promise of this new letter designer.

Franklin left London late in the summer of 1726 thinking that he was done with the craft of

printing forever; he had accepted the offer of a clerkship in the Philadelphia store of Mr.

Denham, a Quaker merchant, and entertained high prospects of eventually establishing a

business of his own in the West Indies. The death of Denham in the spring of 1727 having

dissipated Franklin's hopes, he returned reluctantly to the employ of the printer Samuel

Keimer as the foreman of his shop. There he met Hugh Meredith, earned the esteem of Hugh's

father, and having been offered financial backing by the elder Meredith

agreed to set up a printing house in partnership with the son in the spring of 1728. Franklin

drew up a list of needed equipment amounting to £200 in currency and gave it to Mr.

Meredith, who in turn carried the order to a merchant (

Memoirs, pp.

126, 132, 140, 164). This inventory for the new shop was sent probably with Captain Annis,

clearing Philadelphia customs on October 19, 1727, and docking in London about the first week

of December; the new partners' hope obviously was for delivery on an early sailing in the

spring.

Here then is Franklin's first order of type. He has left us no other record of the

transaction or hints about the assortment of fonts requested — only the task of trying

to reconstruct the inventory and find answers to a series of questions. An analysis of the

type used in his early imprints makes clear that he had commissioned quantities of but six

fonts. Three he planned to use regularly as text letter: the English, pica, and long primer;

two others — the double pica and the French canon — for both limited text-letter

and titling; one, the two line pica, exclusively for titling.[6] In addition he included the usual supply of quotations and a

generous quantity of flowers to match the three sizes of his text type; these he used to

contrive an ingenious array of factotums and page decorations, a marked feature of his

typography throughout his printing career. Foreseeing the likelihood of printing almanacs

years before he conceived the idea of writing and publishing his own Poor

Richards, he ordered an extra quantity of long primer figures and the necessary planet

sorts.

In what amounts and at what cost he purchased this type one can make only a close guess.

Twenty-five years later, on October 27, 1753, Franklin wrote Strahan in London asking him to

order from Caslon a quantity of type for "a small printing office . . . at New Haven," to be

shipped by the first boat in the spring.[7] The itemized list except for the 100 lbs. of great primer and the 50 lbs. of

two line English parallels so nearly the inventory of fonts found in Franklin's early printing

that I offer it as a probable duplication of his first order.

- 300 lbs. long primer, with figures and signs sufficient for an almanac

- 300 lbs. pica

- 100 lbs. great primer

- 300 lbs. English

- 30 lbs. two line capitals and ffowers for different fonts

- 20 lbs. quotations

- 60 lbs. double pica

- 50 lbs. two line English

- 40 lbs. two line great primer[8]

Without the great primer and the two line English the order in aggregate weighs 1050 lbs.,

about one-fourth the weight of the type owned by the firm of Franklin and Hall in 1766.[9] This 1050 lbs. of type purchased in

1728 would have cost Franklin and Meredith at least one-half of their available £200 in

currency (Wroth, op. cit., pp. 65-68).

In this 1753 order one has no difficulty in identifying Caslon as the founder responsible

for casting the fonts; with Franklin's initial order, on the other hand, one wonders whether

or not he designated founder and face, particularly for the distinctive pica and English fonts

which are identical except in size. Franklin's recent sojourn in London would have afforded

him opportunity to decide upon the text letter he preferred, but his disillusioning experience

with Governor Keith and his departure from London thinking that he was done with the printing

craft forever might well have made such a hypothetical selection seem pointless. His pica and

English fonts are slightly larger than those of his competitors Andrew Bradford and Samuel

Keimer, and, I think, considerably more pleasing to the eye; this impression of greater

attractiveness results in part, however, from Franklin's superior presswork and consistently

cleaner case. On one occasion, at least (Memoirs, p. 160), Franklin

stated that the type which he used in The Pennsylvania Gazette was

"better" than that which Keimer had employed earlier in the same publication. Quite possibly

Franklin made the claim because he had personally selected the fonts or relied on a knowing

craftsman in London to select them for him and knew them to be superior to Keimer's; on the

other hand, he may simply have been fortunate in the fonts which the Philadelphia merchant had

secured for him. The fact that Franklin reordered quantities of the identical six fonts in

1731 in order to stock the printing house of his partner Thomas Whitmarsh located in

Charleston, South Carolina, suggests certainly that Franklin had a marked preference for the

type he was then using in his own shop.

In 1728 there were in England at most five foundries from which Franklin might have ordered

his letter: in Oxford, the Andrews foundry, and in London, the foundries of Grover, Mitchell,

James, and an anonymous founder for whom there exist no specific dates of operation.[10] The only recorded extant specimen

book for any of these is that one published together with the sale catalogue of the James

punches and matrices in 1782.

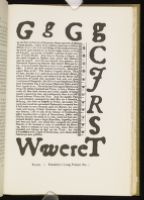

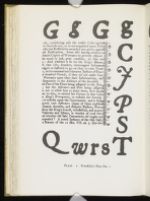

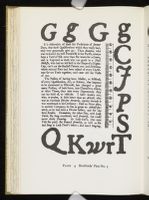

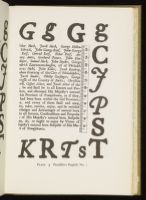

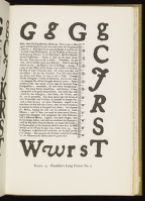

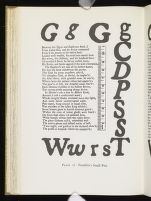

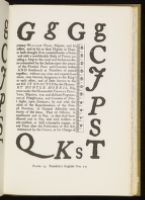

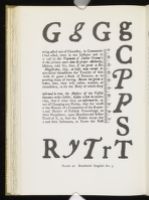

[11] The specimen book includes only a sampling of the extensive holdings of the

James foundry, particularly of the romans and italics, and the history of its compilation is a

tangled one. "The greatest part" of it was done, however, in 1736,

[12] three years after Thomas James had bought up the

matrices of the Andrew foundry and years before John James, his son and successor, had

acquired a portion of the Mitchell foundry and the whole of those belonging to the Grover

foundry, which had ceased operating with the death of its owner early in 1728.

[13] The fonts represented in the

specimen book must therefore have been cast largely from matrices owned in 1728, the year in

which Franklin ordered his letter, by either Andrews or James, and the greater portion of

these, presumably, was owned originally by James. Of the type included in this specimen book

one font is identical with Franklin's, the French canon no. 3, both roman and italic, labeled

further as Berthelet 2, matrices 85, and Berthelet 3, matrices 69 respectively.

[14] Since Franklin was acquainted with

the James foundry and since either Franklin or the Philadelphia merchant ordering the type

would probably have found it more convenient to deal with a London rather than an Oxford

foundry, this French canon titling type and the other five fonts listed in Franklin's 1728

inventory were in all likelihood castings from matrices owned by the James foundry.

These fonts acquired in 1728 at the outset of his career Franklin used steadily for the next

ten years. He did, however, secure in the fall of 1734[15] a small quantity of black letter long primer which he employed

sporadically until 1742. For Franklin the new font served two special uses: one was to mark

the holy days in the text of his Poor Richards; the other was to set

the Gazette advertisements written in the German language, since

Franklin never used in his own shop or in that of Franklin and Hall any German scriptorial

letter. Black letter was by no means a novel type in Philadelphia printing. Andrew Bradford

had small quantities of two black letter sizes — a two line English and a long primer

— from the start of his career in 1713, and he and William Bradford, Jr., his nephew

after him used the identical font of long primer for advertisements in German in their

newspapers. Franklin's original font, readily distinguishable from that of the

Bradfords, bears a family resemblance to the type cut by Christoffel van Dijck and

exhibited in the 1681 specimen of the elder Daniel Elzevir.

[16] The Bradfords', on the other hand, resembles more closely

the black letter English and pica of Oxford University cast from matrices presented by Dr.

Fell.

[17] Fonts derived from both

families of black letter appear among the samples in the James specimen of 1782, but only in

sizes larger than the long primer.

[18]

By 1738 Franklin's printing business had increased enormously. He launched his newspaper in

October of 1729. As early as 1730 he had won from Bradford the position of official printer

for the Pennsylvania General Assembly. In the late fall of 1732 he began publishing the first

of his Poor Richard Almanacks, which soon became so popular that he was

eventually printing annual editions of nearly 10,000 copies. By 1734 he was serving as public

printer for both New Jersey and Delaware, the second known before 1776 as the counties of

New-castle, Kent, and Sussex. His election as Clerk of the Pennsylvania General Assembly in

1736 put him in a position to obtain commissions for even more government printing than he had

enjoyed before. This increased volume obliged him to consider some long range plans for

acquiring additional fonts and for replacing his present text letter which after ten years had

become somewhat rubbed.

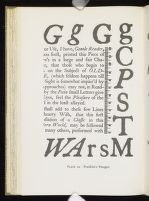

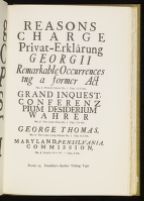

The earliest in a series of purchases of new fonts of text letter appear together in the Gazette on May 4, 1738. The issue is a memorable one, for it marks

Franklin's first use of Caslon type, and possibly the earliest use of Caslon in Colonial

American printing. His first two new fonts were pica and small pica, the second remarkable for

its acute shortage of p and u sorts which obliged Franklin's compositors to substitute

inverted d's and n's consistently until February of 1739. From this point in Franklin's

career, the spring of 1738, until the termination of his partnership with Hall on January 21,

1766, Franklin, with one exception purchased Caslon text type exclusively for use in his

Philadelphia house. The single exception, an obviously non-Caslon font of bourgeois with swash

italic capital A's and N's and a gawky oversized roman capital W, makes only two appearances

in Franklin's recorded printing: one, the slight Catalogue of Choice and

Valuable Books offered for sale in the spring of 1744, and, two, portions of the text of

Nos. 922-926 of the Gazette, running from August 14, to September 11,

1746. How this font came into his hands and when

finally he disposed of it are at present unknown. There is no proof in

Hall's printing that the font was among Franklin's letter when he turned over his shop to his

partner in 1748.

Franklin's first font of Caslon long primer came into use in the Gazette on May 3, 1739, the issue of the previous week, April 26, 1739, revealing his

earliest display of Caslon flowers. By July 17, 1740, he had acquired his first Caslon

brevier, and probably his first Caslon English, although it makes no appearance in the Gazette until September 18, 1740. At this time, or within a year, Franklin

added fonts of Caslon great primer and paragon, a smaller quantity of Caslon double pica, and

an assortment of Caslon titling letter — two line long primer, two line pica, and French

canon. His two line double pica and five line pica, acquired about the same time, are for some

unexplainable reason non-Caslon. Apparently the final purchase in this series was a small

quantity of Caslon black letter brevier used first in the Gazette on

September 2, 1742. Parker, in compiling his inventory of the type owned by the partners in

1766, fixed the weight of all the black letter — both long primer and brevier —

together with "figures, planets, space rules" at a mere 53 lbs. (J. C. Oswald, loc. cit.).

This extensive purchase of Caslon type over a four-year period, 1738-1742, was the last

Franklin was to make for his own shop before turning it over to his partner, David Hall, in

January of 1748. The documents covering these transactions with Caslon, like those for

Franklin's dealings earlier with the James foundry, are missing. The reconstruction is based,

therefore, entirely on the evidence of the appearance of the type in Franklin's signed

printing, particularly in the dated weekly issues of the Gazette, which

for each new font from brevier to English furnished the basis for assigning the approximate

time of purchase and earliest occurrence in Franklin's presswork.

Without the records dealing with these type purchases it is impossible to determine how much

Franklin paid for his new fonts, how exacting he was in designating a particular letter when

Caslon offered for sale a choice of fonts within a given size, and whether or not Franklin

dealt directly with the Caslon foundry. If one may form an opinion based on Franklin's later

purchases, the likelihood is that Franklin dealt indirectly with the Caslon foundry and merely

designated the size of type which he desired to buy. Certainly after 1743, the year in which

Franklin initiated his correspondence with Strahan, it is clear that while Franklin dwelt in

America he ordered his additional Caslon fonts through Strahan and relied on his judgment in

selecting the most suitable letter.[19]

Parker's itemized inventory of the type owned by Franklin and Hall in 1766 does make it

possible, however, to state with some certainty in what quantity Franklin purchased several of

these first Caslon fonts. Parker lists the following:

- 436 lbs. Long Primer, well worn

- 318 lbs. Small Pica, almost worn out

- 421 lbs. Pica, Old, and much batter'd

- 334 lbs. Old English, fit for little more than old metal

- 223 lbs. Great Primer, well worn

- 158 lbs. Double Pica, pretty good

- 91 lbs. Double English Do.[20]

All of these, which represent but a portion of Parker's total inventory, I have associated

with Franklin's original purchase of Caslon type only because I have found no clear evidence

either in the printed matter or in the extant manuscripts to indicate that Franklin bought

later additional quantities of these fonts. The one exception is a later font of Caslon

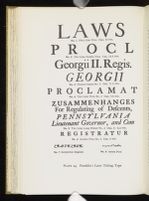

English, but Parker clearly distinguishes it from the older one: "502 lbs. Newer English,

nearly half worn" (J. C. Oswald, loc. cit.). This newer Caslon English,

acquired in order that Hall might undertake a large piece of government printing in folio, had

appeared first in the printing of the laws of the General Assembly for April 5, 1756, while

the older Caslon English seems last to have been employed in the printing of the laws for

February 3, 1756. Parker's noting the existence of the two English fonts in 1766 makes clear

that though Hall had acquired a fresh font of English some ten years before, he had not seen

fit to scrap his worn one.

Thus it is possible to explain how Franklin and Hall kept possession of their original font

of Caslon English for a period of twenty-six years. They used it for sixteen years, and once

it had worn out, merely kept it in storage for the next ten. But what of the other original

Caslon fonts which they retained for an equally long period and kept in use? Part of the

explanation certainly is that Franklin and Hall were loath to lay out any more money on type

than they needed to. They expected their business to yield a substantial income, and to

achieve this objective in troubled times with an unstable economy was no simple task.

Moreover, Hall was a frugal man who tended to make do with what materials he possessed so long

as they were tolerable. But a more important part of the explanation is the kind of printing

they were engaged in and the demands that that printing made on their various sizes of type.

From 1728 to 1738 Franklin regularly used English,

pica, and long primer in

his newspaper, long primer in the almanacs, and long primer and pica predominantly in the

books he printed. Thereafter he began to use smaller and smaller fonts in the

Gazette. The English disappeared, then the pica, and finally much of the

small pica. After 1739 he fixed upon long primer and brevier, then all brevier, and

eventually, brevier and bourgeois, but neither Franklin nor Hall was happy over their purchase

of the bourgeois and wished they had bought brevier instead. The almanacs continued to be set

in long primer, but this printing involved long years of standing type which made

comparatively small additional demands on their font of long primer. As early as 1729 Franklin

had begun printing annually in folio the laws of the Province and the votes and proceedings of

the General Assembly; the large collected editions of these laws of Pennsylvania and those of

the neighboring provinces followed in the forties and fifties. The font which Franklin and

Hall used for their text letter was English and the section headings they set in the larger

great primer, double pica, and double English. For the more sporadic portion of their printing

— the pamphlets and books published in small editions — Franklin and Hall used

their small pica and pica, or English. Hence the fonts which they worked hardest and needed

most often to replace were the brevier and the English. The other fonts, the long primer,

small pica, pica, great primer, double pica, and double English, they used more sparingly, and

therefore understandably it was these sizes of the original Caslon purchase that remained

tolerably serviceable from the time of their acquisition in 1738-1742 to the termination of

the partnership early in 1766.

When Franklin turned over his shop on January 21, 1748, to his new partner, he put into

Hall's hands a stock of all-Caslon text type from eight to ten years old. The purchasing of

any additional fonts was to be Franklin's responsibility,[21] though by stipulation in the articles of agreement the two men

were to share jointly in the expense.[22] The font first in need of replacement was, quite predictably, the brevier,

which with ten years of hard wear in the Gazette had become markedly

worn; it lingered in the standing type of a few advertisements until December 19, 1752, more

than two years after the new Caslon brevier had been pressed into service on September 27,

1750.[23] Franklin placed

the order for this new type through Strahan just as he was to do with that for

the new Caslon English mentioned earlier, which was commissioned in the summer and again in

the fall of 1755 (HLB I, August 28, 1755) and first used in the spring of 1756 for printing

one group of the laws.

Also in the fall of 1755 both Franklin[24] and Hall were in correspondence with Strahan about a new small-body font.

Hall wanted "500 weight" of a font, "Body of Brevier with long primer face & if not with a

Long primer Face, with one betwixt a long primer and Brevier" (HLB I, August 28, 1755). Caslon

having cast the letter during the winter, Strahan in early March shipped "The Fount of Brevier

. . . on Board Captain Reeve, who was ready to sail when an Embargo was clapt on all our

Shipping for Six Weeks" (HLB I, March 13, 1756). The type arrived finally in time to be used

in the Gazette on June 24, 1756. Franklin writing to Strahan from New

York on July 2, remarked that "the brevier fount . . . came to hand in good order and pleases

Mr. Hall and me very much."[25] In a

reply to Hall written in September Strahan noted that "the new Letter in your Newspaper . . .

looks very well" (HLB I, September 11, 1756). Then the storm broke. Hall discovered that he

had received not a large face-small body font, but all bourgeois, and shortly thereafter

Franklin discovered further that Caslon had billed him for a font of brevier at 2/6 per pound

rather than for a font of bourgeois, which should have cost a half shilling less. Franklin

felt put upon. He had paid £58/17/6 for the font, had been overcharged £11/15/6,

and immediately wrote Strahan somewhat sharply requesting that he see Caslon about a refund,

which we may infer was forthcoming since Franklin made no later reference to the matter.[26] An analysis of the bill reveals,

incidentally, that the precise weight of the letter was 471 lbs.

When Hall next had occasion to ask his partner to buy some new letter, Franklin was residing

in London, having arrived there in July of 1757. When Hall's request reached him in the spring

of 1758, he went directly to the foundry to place the order. Caslon cast the font — 192

lbs. of bourgeois — over the summer, and Franklin arranged for it to be shipped in

September. The shipping was delayed, however, so that the type did not reach Philadelphia

until the following spring.[27]

What Hall wanted was not bourgeois but brevier. "The old Letter is shockingly bad," he wrote

Franklin on March 5, 1760, "and I don't care to use the Bourgois [in the Gazette advertisement], for the Reason

I have several times given

you, that it drives out so much . . . ."

[28] Franklin, having apparently realized his mistake some weeks earlier, had

ordered Caslon to cast 300 lbs. of brevier at once. The font reached Hall on June 5, 1760 (HLB

II, July 2, 1760), and first appeared in the

Gazette on June 19. The

precise composition of this font, the last which Franklin was to purchase for the firm of

Franklin and Hall, he described to Hall in a letter dated March 28, 1760: "I order'd the Fount

all Roman, as it will hold out better in the same Quantity of Work, having but half the Chance

of Wanting Sorts, that the same Weight of Rom. & Ital. would have, and the old Italic is

not so much worn as the Roman, and so may serve a little longer."

[29] The best that Hall could reply was, "The Brevier . . .

looks very well, but sticks when distributed most intolerably (HLB II, July 2, 1760); and six

months later, "The Brevier seems pretty perfect, only the lower Case s's run short . . . ."

(HLB II, February 9, 1761). Thus the problem of insufficient sorts continued to plague

Franklin. It had caused him to try his hand at casting type while he still worked for Keimer;

it reduced him to an unhappy expedient in working with his new Caslon small pica in 1738; it

caused Hall through the years to write Strahan repeatedly for small quantities of individual

letters,

[30] and Franklin was yet

to face in the closing years and even final months of his life the wrangling correspondence

with Francis Childs over the short sorts in the old Passy fonts.

[31]

By July of 1761, a little more than a year after Franklin had sent over the last font of

Caslon brevier, Hall was urging him to order a like quantity of the same letter to be shipped

at once. The Gazette advertisements were becoming so bulky that he was

obliged "to distribute the standing ones in order to set up the new" (HLB II, July 20, 1761).

Franklin allowed the request to go unheeded so involved had he become by this time in the

responsibilities of his work as provincial agent. Eventually Hall understood that Franklin

could no longer be expected to perform even these occasional chores for the firm, and on

November 21, 1764, Hall asked Strahan to secure for him 500 lbs. of Caslon brevier, despite

the fact that at that moment Franklin was again on the high seas bound for London, after

returning to America

in the fall of 1762. Hall explained further: "Mr.

Franklin used to send for the Printing Letter, but as his Time and mine will, in all

probability be out before I have the Pleasure of seeing him again what comes now will be in my

Name . . . ." (HLB II, November 21, 1764).

When the partnership terminated in January of 1766, Hall took over the shop and shortly

thereafter joined in a new business agreement with a former employee, William Sellers. Their

type save for the newly acquired font of brevier consisted of the stock previously owned by

Franklin and Hall. In quantity and variation of size the letter was extensive, but as Parker

explained to Franklin, ". . . indeed the whole is worn much, except the Double Pica and newest

English, tho' neither of them are new."[32] Within six months Hall had begun ordering replacements for the old fonts,

starting with the long primer and titling type (HLB III, June 7, 1766). Only one of Franklin's

1728 type acquisitions, the James' French canon, remained in use throughout the 38 years of

Franklin's association with the Philadelphia printing house, and passed into the possession of

Hall and Sellers. I found it used only once, and this in a line of long standing type. Within

the year it had disappeared.

This then is the history of the fonts of type which Franklin employed in his Philadelphia

shop from 1728 to 1766, and the necessary preliminary to the consideration of one final

question: With what certainty is it now possible to identify as Franklin's a piece of

printing, unsigned or issued as the work of another, which falls within the 38 years of his

active printing career and which is by some fashion connected with Pennsylvania, New Jersey,

or Delaware? The answer is best divided into two parts. During the greater portion of

Franklin's career as the master of his own shop, from the spring of 1728 to the late summer of

1743, I believe it possible to identify positively on the evidence of the type just about any

piece of unsigned Franklin printing. In 1728 Franklin had but two competitors in Philadelphia.

The less significant was his old employer, Samuel Keimer, whose meager holdings of text type

consisted of two fonts of English and one each of pica and long primer, all of them readily

distinguishable from Franklin's. Keimer sold his shop to David Harry in 1729 and went to

Barbados where Harry joined him in 1730, "taking the printing house with him" (Memoirs, p. 174). Franklin's more formidable competitor was, of course,

Andrew Bradford, whose type holdings exceeded Franklin's but differed from them in every font.

One, therefore, can distinguish

Franklin's printing from that of Andrew

Bradford during the years 1728-1742, and from that of Cornelia Bradford, his widow, who

directed the business actively until 1746. Christopher Sauer set up his press in Germantown in

1738, but his type also differed from Franklin's as did the fonts of both Peter Zenger and

William Bradford, Sr. in New York. There were no printers in New Jersey or Delaware.

The second part of the answer involves complications. It covers the period of 1743 to 1766,

the last few years of Franklin's sole proprietorship and the whole of his partnership with

Hall. In 1742 Franklin completed his series of purchases of all-Caslon fonts; by 1743 he had

disposed of the last of his original James letter except for the seldom seen French canon,

which persisted until 1766. It is this array of new Caslon letter acquired by Franklin that at

one and the same time presents the surest basis for identifying his later unsigned presswork,

and the gravest obstacle. The chief complicating factor is Andrew Bradford's nephew, William

Bradford, Jr., who opened his Philadelphia shop about July 1, 1742, and had acquired by early

September 1743, a font of Caslon English, by December 1745, a font of Caslon pica, and by

December 1746, a font of Caslon long primer. He did possess from the outset, however,

non-Caslon fonts of English and long primer, and an assortment of non-Caslon titling letter.

Further, he used printer's ornaments only rarely, none of them cast by Caslon. Had he

continued systemically to purchase additional Caslon type, the problem of differentiating his

printing from Franklin's on the basis of the letter alone would have proved all but

insolvable. Fortunately for this study he did not. His two later fonts of bourgeois are

non-Caslon, and he seems never to have owned a font of brevier.

Further, when William's uncle, Andrew Bradford died, he stipulated in his will that the

nephew was to receive at the death of Cornelia Bradford — she died in 1755 — all

of his "Printing Press Letter . . . if he shall behave himself handsomely towards her."[33] According to Isaiah Thomas,

Cornelia had been responsible for disrupting an earlier partnership between Andrew and his

nephew;[34] therefore William's

chances of acquiring his uncle's fonts before 1755, if at all, would seem remote. But the

letter in William's publications tells another story. By 1746 William was using Andrew's

newest font of English, and by 1752 he appears to have gained possession of much of the

remainder of Andrew's stock of type. Since Franklin and later Hall used only Caslon fonts and

William Bradford, Jr., both Caslon and non-Caslon type,

particularly the

second after falling heir to his late uncle's letter, it is possible with close study to

distinguish most later unsigned Franklin printing from that of Bradford. The identification of

unsigned Bradford printing set in Caslon English and long primer is made the easier after 1748

by the fouling of these cases with non-Caslon sorts.

Other than Franklin and the Bradfords, who were printing almost entirely in the English

language, and Christopher Sauer, who was printing more in German than in English, Philadelphia

in the 1740's had only a trio of struggling minor German printers — Joseph Crell and two

Franklin partners, Gotthard Armbruster and Johan Boehm — all employing non-Caslon fonts

or German scriptorial letter. In the large cities to the north, however, the important

printers were all equipping their houses with Caslon. In New York City Franklin established a

silent partnership with James Parker, the successor to the retiring William Bradford, Sr., and

fitted the new shop with a complete stock of Caslon type by 1743. In Boston by the mid-forties

Rogers and Fowle, Kneeland and Green, Gookin, and Henchman had all acquired Caslon fonts.

In the 1750's two of the three new printers in English to set up shop in Philadelphia were

men trained by Franklin, James Chattin and William Dunlap, the latter a Franklin partner in

Lancaster before moving to Philadelphia. The third newcomer was Andrew Steuart. Chattin,

active from 1752 to 1758, first in Lancaster and later in Philadelphia, possessed in addition

to his Caslon English, long primer, and brevier, an assortment of distinctive non-Caslon

fonts, which makes it relatively simple to distinguish much of his printing from Franklin and

Hall's. Dunlap and Steuart, on the other hand, both starting their careers in 1758, reveal

almost from the outset all-Caslon letter. Further-more, by 1754 James Parker had set up a

printing house in Wood-bridge, New Jersey, employing Caslon type entirely, and by 1761, James

Adams, a Franklin-trained printer, had begun using Caslon in his new shop located in

Wilmington, Delaware.

The two new Philadelphia printers in the early sixties were Peter Miller and Henry Miller,

craftsmen whose houses were stocked with both German scriptorial and English roman and italic

letter. The chief difference between the two is that Henry Miller, a former Franklin

journeyman, employed for his publications in English all-Caslon text and titling type while

Peter used largely non-Caslon fonts.

This increasingly widespread use of Caslon by the printers both in Philadelphia and in the

neighboring provinces makes it most difficult after 1753 to identify by means of the letter

alone an unsigned Franklin

and Hall publication, and between 1758 and 1766,

well nigh impossible.