63. CHAPTER LXIII.

IT was evening when Philip took the cars at the Ilium

station. The news of his success had preceded him, and

while he waited for the train, he was the center of a group of

eager questioners, who asked him a hundred things about the

mine, and magnified his good fortune. There was no mistake

this time.

Philip, in luck, had become suddenly a person of consideration,

whose speech was freighted with meaning, whose looks

were all significant. The words of the proprietor of a rich

coal mine have a golden sound, and his common sayings are

repeated as if they were solid wisdom.

Philip wished to be alone; his good fortune at this moment

seemed an empty mockery, one of those sarcasms of fate,

such as that which spreads a dainty banquet for the man who

has no appetite. He had longed for success principally for

Ruth's sake; and perhaps now, at this very moment of his

triumph, she was dying.

“Shust what I said, Mister Sderling,” the landlord of the

Ilium hotel kept repeating. “I dold Jake Schmidt he find

him dere shust so sure as noting.”

“You ought to have taken a share, Mr. Dusenheimer,” said

Philip.

“Yaas, I know. But d'old woman, she say `You sticks to

your pisiness. So I sticks to 'em. Und I makes noting. Dat

Mister Prierly, he don't never come back here no more, ain't

it?”

“Why?” asked Philip.

“Vell, dere is so many peers, und so many oder dhrinks, I

got 'em all set down, ven he coomes back.”

It was a long night for Philip, and a restless one. At any

other time the swing of the cars would have lulled him to

sleep, and the rattle and clank of wheels and rails, the roar of

the whirling iron would have only been cheerful reminders

of swift and safe travel. Now they were voices of warning

and taunting; and instead of going rapidly the train seemed

to crawl at a snail's pace. And it not only crawled, but it

frequently stopped; and when it stopped it stood dead still,

and there was an ominous silence. Was anything the matter,

he wondered. Only a station probably. Perhaps, he thought,

a telegraphic station. And then he listened eagerly. Would

the conductor open the door and ask for Philip Sterling, and

hand him a fatal dispatch?

How long they seemed to wait. And then slowly beginning

to move, they were off again, shaking, pounding, screaming

through the night. He drew his curtain from time to

time and looked out. There was the lurid sky line of the

wooded range along the base of which they were crawling.

There was the Susquehannah, gleaming in the moon-light.

There was a stretch of level valley with silent farm houses,

the occupants all at rest, without trouble, without anxiety.

There was a church, a graveyard, a mill, a village; and now,

without pause or fear, the train had mounted a trestle-work

high in air and was creeping along the top of it while a swift

torrent foamed a hundred feet below.

What would the morning bring? Even while he was flying

to her, her gentle spirit might have gone on another

flight, whither he could not follow her. He was full of fore-boding.

He fell at length into a restless doze. There was a

noise in his ears as of a rushing torrent when a stream is

swollen by a freshet in the spring. It was like the breaking

up of life; he was struggling in the consciousness of coming

death: when Ruth stood by his side, clothed in white, with

a face like that of an angel, radiant, smiling, pointing to the

sky, and saying, “Come.” He awoke with a cry—the train

was roaring through a bridge, and it shot out into daylight.

When morning came the train was industriously toiling

along through the fat lands of Lancaster, with its broad farms

of corn and wheat, its mean houses of stone, its vast barns

and granaries, built as if for storing the riches of Heliogabalus.

Then came the smiling fields of Chester, with their

English green, and soon the county of Philadelphia itself,

and the increasing signs of the approach to a great city. Long

trains of coal cars, laden and unladen, stood upon sidings;

the tracks of other roads were crossed; the smoke of other

locomotives was seen on parallel lines; factories multiplied;

streets appeared; the noise of a busy city began to fill the air;

and with a slower and slower clank on the connecting rails

and interlacing switches the train rolled into the station and

stood still.

It was a hot August morning. The broad streets glowed

in the sun, and the white-shuttered houses stared at the hot

thoroughfares like closed bakers'-ovens set along the highway.

Philip was oppressed with the heavy air; the sweltering

city lay as in a swoon. Taking a street car, he rode away to

the northern part of the city, the newer portion, formerly the

district of Spring Garden, for in this the Boltons now lived,

in a small brick house, befitting their altered fortunes.

He could scarcely restrain his impatience when he came in

sight of the house. The window shutters were not “bowed”;

thank God, for that. Ruth was still living, then. He ran

up the steps and rang. Mrs. Bolton met him at the door.

“Thee is very welcome, Philip.”

“And Ruth?”

“She is very ill, but quieter than she has been, and the

fever is a little abating. The most daugerous time will be

when the fever leaves her. The doctor fears she will not

have strength enough to rally from it. Yes, thee can see

her.”

Mrs. Bolton led the way to the little chamber where Ruth

lay. “Oh,” said her mother, “if she were only in her cool

and spacious room in our old home. She says that seems like

heaven.”

Mr. Bolton sat by Ruth's bedside, and he rose and silently

pressed Philip's hand. The room had but one window; that

was wide open to admit the air, but the air that came in was

hot and lifeless. Upon the table stood a vase of flowers.

Ruth's eyes were closed; her cheeks were flushed with fever,

and she moved her head restlessly as if in pain.

“Ruth,” said her mother, bending over her, “Philip is

here.”

Ruth's eyes unclosed, there was a gleam of recognition in

them, there was an attempt at a smile upon her face, and she

tried to raise her thin hand, as Philip touched her forehead

with his lips; and he heard her murmur,

“Dear Phil.”

There was nothing to be done but to watch and wait for

the cruel fever to burn itself out. Dr. Longstreet told Philip

that the fever had undoubtedly been contracted in the hospital,

but it was not malignant, and would be little dangerous

if Ruth were not so worn down with work, or if she had a

less delicate constitution.

“It is only her indomitable will that has kept her up for

weeks. And if that should leave her now, there will be no

hope. You can do more for her now, sir, than I can?”

“How?” asked Philip eagerly.

“Your presence, more than anything else, will inspire her

with the desire to live.”

When the fever turned, Ruth was in a very critical condition.

For two days her life was like the fluttering of a

lighted candle in the wind. Philip was constantly by her

side, and she seemed to be conscious of his presence, and to

cling to him, as one borne away by a swift stream clings to a

stretched-out hand from the shore. If he was absent a moment

her restless eyes sought something they were disappointed

not to find.

Philip so yearned to bring her back to life, he willed it so

strongly and passionately, that his will appeared to affect hers

and she seemed slowly to draw life from his.

After two days of this struggle with the grasping enemy,

it was evident to Dr. Longstreet that Ruth's will was beginning

to issue its orders to her body with some force, and

that strength was slowly coming back. In another day there

was a decided improvement. As Philip sat holding her weak

hand and watching the least sign of resolution in her face,

Ruth was able to whisper,

“I so want to live, for you, Phil!”

“You will, darling, you must,” said Philip in a tone of

faith and courage that carried a thrill of determination—of

command—along all her nerves.

Slowly Philip drew her back to life. Slowly she came

back, as one willing but well high helpless. It was new for

Ruth to feel this dependence on another's nature, to consciously

draw strength of will from the will of another. It

was a new but a dear joy, to be lifted up and carried back

into the happy world, which was now all aglow with the

light of love; to be lifted and carried by the one she loved

more than her own life.

“Sweetheart,” she said to Philip, “I would not have

cared to come back but for thy love.”

“Not for thy profession?”

“Oh, thee may be glad enough of that some day, when thy

coal bed is dug out and thee and father are in the air again.”

When Ruth was able to ride she was taken into the country,

for the pure air was necessary to her speedy recovery.

The family went with her. Philip could not be spared from

her side, and Mr. Bolton had gone up to Ilium to look into

that wonderful coal mine and to make arrangements for developing

it, and bringing its wealth to market. Philip had

insisted on re-conveying the Ilium property to Mr. Bolton,

retaining only the share originally contemplated for himself,

and Mr. Bolton, therefore, once more found himself engaged

in business and a person of some consequence in Third street.

The mine turned out even better than was at first hoped, and

would, if judiciously managed, be a fortune to them all. This

also seemed to be the opinion of Mr. Bigler, who heard of it

as soon as anybody, and, with the impudence of his class

called upon Mr. Bolton for a little aid in a patent car-wheel

he had bought an interest in. That rascal, Small, he said,

had swindled him out of all he had.

Mr. Bolton told him he was very sorry, and recommended

him to sue Small.

Mr. Small also came with a similar story about Mr. Bigler;

and Mr. Bolton had the grace to give him like advice. And

he added, “If you and Bigler will procure the indictment of

each other, you may have the satisfaction of putting each

other in the penitentiary for the forgery of my acceptances.”

Bigler and Small did not quarrel however. They both

attacked Mr. Bolton behind his back as a swindler, and circulated

the story that he had made a fortune by failing.

In the pure air of the highlands, amid the golden glories of

ripening September, Ruth rapidly came back to health. How

beautiful the world is to an invalid, whose senses are all clarified,

who has been so near the world of spirits that she is

sensitive to the finest influences, and whose frame responds

with a thrill to the subtlest ministrations of soothing nature.

Mere life is a luxury, and the color of the grass, of the

flowers, of the sky, the wind in the trees, the out-lines of the

horizon, the forms of clouds, all give a pleasure as exquisite

as the sweetest music to the ear famishing for it. The world

was all new and fresh to Ruth, as if it had just been created

for her, and love filled it, till her heart was overflowing with

happiness.

It was golden September also at Fallkill. And Alice sat

by the open window in her room at home, looking out upon

the meadows where the laborers were cutting the second crop

of clover. The fragrance of it floated to her nostrils. Perhaps

she did not mind it. She was thinking. She had just been

writing to Ruth, and on the table before her was a yellow

piece of paper with a faded four-leaved clover pinned on it—

only a memory now. In her letter to Ruth she had poured

out her heartiest blessings upon them both, with her dear love

forever and forever.

“Thank God,” she said, “they will never know.”

They never would know. And the world never knows

how many women there are like Alice, whose sweet but

lonely lives of self-sacrifice, gentle, faithful, loving souls, bless

it continually.

“She is a dear girl,” said Philip, when Ruth showed him

the letter.

“Yes, Phil, and we can spare a great deal of love for her,

our own lives are so full.”

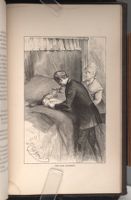

[ILLUSTRATION]

[Description: 499EAF. Epigraph.]