The gilded age a tale of to-day |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. | CHAPTER XVIII. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. |

| 30. |

| 31. |

| 32. |

| 33. |

| 34. |

| 35. |

| 36. |

| 37. |

| 38. |

| 39. |

| 40. |

| 41. |

| 42. |

| 43. |

| 44. |

| 45. |

| 46. |

| 47. |

| 48. |

| 49. |

| 50. |

| 51. |

| 52. |

| 53. |

| 54. |

| 55. |

| 56. |

| 57. |

| 58. |

| 59. |

| 60. |

| 61. |

| 62. |

| 63. |

| CHAPTER XVIII. The gilded age | ||

18. CHAPTER XVIII.

[ILLUSTRATION] [Description: 499EAF. Epigraph.]

Bedda ag Idda.

Que voill que m prendats a moiler.

—Qu'en aissi l'a Dieus establida

Per que not pot esser partida.”

Roman de Jaufre.

EIGHT years have passed since the death of Mr. Hawkins.

Eight years are not many in the life of a nation or the

history of a state, but they may be years of destiny that shall

fix the current of the century following. Such years were

those that followed the little scrimmage on Lexington Common.

Such years were those that followed the double-shotted

demand for the surrender of Fort Sumter. History is never

done with inquiring of these years, and summoning witnesses

about them, and trying to understand their significance.

The eight years in America from 1860 to 1868 uprooted

institutions that were centuries old, changed the politics of a

people, transformed the social life of half the country, and

wrought so profoundly upon the entire national character

that the influence cannot be measured short of two or three

generations.

As we are accustomed to interpret the economy of providence,

the life of the individual is as nothing to that of the

nation or the race; but who can say, in the broader view and

the more intelligent weight of values, that the life of one

not a tribunal where the tragedy of one human soul shall not

seem more significant than the overturning of any human

institution whatever?

When one thinks of the tremendous forces of the upper

and the nether world which play for the mastery of the soul

of a woman during the few years in which she passes from

plastic girlhood to the ripe maturity of womanhood, he may

well stand in awe before the momentous drama.

What capacities she has of purity, tenderness, goodness;

what capacities of vileness, bitterness and evil. Nature must

needs be lavish with the mother and creator of men, and

centre in her all the possibilities of life. And a few critical

years can decide whether her life is to be full of sweetness

and light, whether she is to be the vestal of a holy temple,

or whether she will be the fallen priestess of a desecrated

shrine. There are women, it is true, who seem to be capable

neither of rising much nor of falling much, and whom a

conventional life saves from any special development of

character.

But Laura was not one of them. She had the fatal gift of

beauty, and that more fatal gift which does not always accompany

mere beauty, the power of fascination, a power that

may, indeed, exist without beauty. She had will, and pride

and courage and ambition, and she was left to be very much

her own guide at the age when romance comes to the aid of

passion, and when the awakening powers of her vigorous

mind had little object on which to discipline themselves.

The tremendous conflict that was fought in this girl's soul

none of those about her knew, and very few knew that her

life had in it anything unusual or romantic or strange.

Those were troublous days in Hawkeye as well as in most

other Missouri towns, days of confusion, when between

Unionist and Confederate occupations, sudden maraudings

and bush-whackings and raids, individuals escaped observation

or comment in actions that would have filled the town

with scandal in quiet times.

Fortunately we only need to deal with Laura's life at this

will serve to reveal the woman as she was at the time of the

arrival of Mr. Harry Brierly in Hawkeye.

The Hawkins family were settled there, and had a hard

enough struggle with poverty and the necessity of keeping

up appearances in accord with their own family pride and the

large expectations they secretly cherished of a fortune in the

Knobs of East Tennessee. How pinched they were perhaps

no one knew but Clay, to whom they looked for almost their

whole support. Washington had been in Hawkeye off and

on, attracted away occasionally by some tremendous speculation,

from which he invariably returned to Gen. Boswell's

office as poor as he went. He was the inventor of no one

knew how many useless contrivances, which were not worth

patenting, and his years had been passed in dreaming and

planning to no purpose; until he was now a man of about

thirty, without a profession or a permanent occupation, a tall,

brown-haired, dreamy person of the best intentions and the

frailest resolution. Probably however the eight years had

been happier to him than to any others in his circle, for the

time had been mostly spent in a blissful dream of the coming

of enormous wealth.

He went out with a company from Hawkeye to the war,

and was not wanting in courage, but he would have been a

better soldier if he had been less engaged in contrivances for

circumventing the enemy by strategy unknown to the books.

It happened to him to be captured in one of his self-appointed

expeditions, but the federal colonel released him,

after a short examination, satisfied that he could most injure

the confederate forces opposed to the Unionists by returning

him to his regiment.

Col. Sellers was of course a prominent man during the

war. He was captain of the home guards in Hawkeye, and

he never left home except upon one occasion, when on the

strength of a rumor, he executed a flank movement and fortified

Stone's Landing, a place which no one unacquainted with

the country would be likely to find.

“Gad,” said the Colonel afterwards, “the Landing is the

CAPTURE OF WASHINGTON.

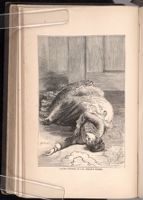

[Description: 499EAF. Page 171. In-line image of a man being roughed up by a group of military soldiers.] key to upper Missouri, and it is the only place the enemynever captured. If other places had been defended as well as

that was, the result would have been different, sir.”

The Colonel had his own theories about war as he had in

other things. If everybody had stayed at home as he did, he

said, the South never would have been conquered. For what

would there have been to conquer? Mr. Jeff Davis was constantly

writing him to take command of a corps in the confederate

army, but Col. Sellers said, no, his duty was at home.

And he was by no means idle. He was the inventor of the

famous air torpedo, which came very near destroying the

Union armies in Missouri, and the city of St. Louis itself.

His plan was to fill a torpedo with Greek fire and poisonous

and deadly missiles, attach it to a balloon, and then let it sail

away over the hostile camp and explode at the right moment,

when the time-fuse burned out. He intended to use this

invention in the capture of St. Louis, exploding his torpedoes

over the city, and raining destruction upon it until

the army of occupation would gladly capitulate. He was unable

to procure the Greek fire, but he constructed a vicious

torpedo which would have answered the purpose, but the first

away, and setting fire to his house. The neighbors helped

him put out the conflagration, but they discouraged any

more experiments of that sort.

The patriotic old gentleman, however, planted so much

powder and so many explosive contrivances in the roads leading

into Hawkeye, and then forgot the exact spots of danger,

that people were afraid to travel the highways, and used to

come to town across the fields. The Colonel's motto was,

“Millions for defence but not one cent for tribute.”

When Laura came to Hawkeye she might have forgotten

the annoyances of the gossips of Murpheysburg and have outlived

the bitterness that was growing in her heart, if she had

been thrown less upon herself, or if the surroundings of her

life had been more congenial and helpful. But she had little

society, less and less as she grew older that was congenial to

her, and her mind preyed upon itself, and the mystery of her

birth at once chagrined her and raised in her the most extravagant

expectations.

She was proud and she felt the sting of poverty. She

could not but be conscious of her beauty also, and she was

vain of that, and came to take a sort of delight in the exercise

of her fascinations upon the rather loutish young men who

came in her way and whom she despised.

There was another world opened to her—a world of books.

But it was not the best world of that sort, for the small

libraries she had access to in Hawkeye were decidedly miscellaneous,

and largely made up of romances and fictions which

fed her imagination with the most exaggerated notions of life,

and showed her men and women in a very false sort of

heroism. From these stories she learned what a woman of

keen intellect and some culture joined to beauty and fascination

of manner, might expect to accomplish in society as she

read of it; and along with these ideas she imbibed other very

crude ones in regard to the emancipation of woman.

There were also other books—histories, biographies of

those of Byron, Scott and Shelley and Moore, which she eagerly

absorbed, and appropriated therefrom what was to her liking.

Nobody in Hawkeye had read so much or, after a fashion,

studied so diligently as Laura. She passed for an accomplished

girl, and no doubt thought herself one, as she was,

judged by any standard near her.

During the war there came to Hawkeye a confederate

officer, Col. Selby, who was stationed there for a time, in

command of that district. He was a handsome, soldierly

man of thirty years, a graduate of the University of Virginia,

and of distinguished family, if his story might be believed,

and, it was evident, a man of the world and of extensive

travel and adventure.

To find in such an out of the way country place a woman

like Laura was a piece of good luck upon which Col. Selby

congratulated himself. He was studiously polite to her and

treated her with a consideration to which she was unaccustomed.

She had read of such men, but she had never seen

one before, one so high-bred, so noble in sentiment, so entertaining

in conversation, so engaging in manner.

It is a long story; unfortunately it is an old story, and it

need not be dwelt on. Laura loved him, and believed that

his love for her was as pure and deep as her own. She worshipped

him and would have counted her life a little thing to

give him, if he would only love her and let her feed the hunger

of her heart upon him.

The passion possessed her whole being, and lifted her up,

till she seemed to walk on air. It was all true, then, the

romances she had read, the bliss of love she had dreamed of.

Why had she never noticed before how blithesome the world

was, how jocund with love; the birds sang it, the trees whispered

it to her as she passed, the very flowers beneath her

feet strewed the way as for a bridal march.

When the Colonel went away they were engaged to be

married, as soon as he could make certain arrangements

He wrote to her from Harding, a small town in the southwest

corner of the state, saying that he should be held in the

service longer than he had expected, but that it would not be

more than a few months, then he should be at liberty to take her

to Chicago where he had property, and should have business,

either now or as soon as the war was over, which he thought

could not last long. Meantime why should they be separated?

He was established in comfortable quarters, and if she

could find company and join him, they would be married,

and gain so many more months of happiness.

Was woman ever prudent when she loved? Laura went

to Harding, the neighbors supposed to nurse Washington

who had fallen ill there.

Her engagement was, of course, known in Hawkeye, and

was indeed a matter of pride to her family. Mrs. Hawkins

would have told the first inquirer that Laura had gone to be

married; but Laura had cautioned her; she did not want to

be thought of, she said, as going in search of a husband; let

the news come back after she was married.

So she traveled to Harding on the pretence we have mentioned,

and was married. She was married, but something

must have happened on that very day or the next that

alarmed her. Washington did not know then or after what

it was, but Laura bound him not to send news of her marriage

to Hawkeye yet, and to enjoin her mother not to speak

of it. Whatever cruel suspicion or nameless dread this was,

Laura tried bravely to put it away, and not let it cloud her

happiness.

Communication that summer, as may be imagined, was

neither regular nor frequent between the remote confederate

camp at Harding and Hawkeye, and Laura was in a measure

lost sight of—indeed, everyone had troubles enough of his

own without borrowing from his neighbors.

Laura had given herself utterly to her husband, and if he

had faults, if he was selfish, if he was sometimes coarse, if

the passion of her life, the time when her whole nature

went to flood tide and swept away all barriers. Was her

husband ever cold or indifferent? She shut her eyes to

everything but her sense of possession of her idol.

Three months passed. One morning her husband informed

her that he had been ordered South, and must go within two

hours.

“I can be ready,” said Laura, cheerfully.

“But I can't take you. You must go back to Hawkeye.”

“Can't—take—me?” Laura asked, with wonder in her

eyes. “I can't live without you. You said”—

“O bother what I said”—and the Colonel took up his

sword to buckle it on, and then continued coolly, “the fact is

Laura, our romance is played out.”

Laura heard, but she did not comprehend. She caught his

arm and cried, “George, how can you joke so cruelly? I

will go any where with you. I will wait any where. I can't

go back to Hawkeye.”

“Well, go where you like. Perhaps,” continued he with

a sneer, “you would do as well to wait here, for another

colonel.”

Laura's brain whirled. She did not yet comprehend.

“What does this mean? Where are you going?”

“It means,” said the officer, in measured words, “that you

haven't anything to show for a legal marriage, and that I am

going to New Orleans.”

“It's a lie, George, it's a lie. I am your wife. I shall go.

I shall follow you to New Orleans.”

“Perhaps my wife might not like it!”

Laura raised her head, her eyes flamed with fire, she tried

to utter a cry, and fell senseless on the floor.

When she came to herself the Colonel was gone. Washington

Hawkins stood at her bedside. Did she come to herself

Was there anything left in her heart but hate and

bitterness, a sense of an infamous wrong at the hands of the

only man she had ever loved?

She returned to Hawkeye. With the exception of Washington

and his mother, no one knew what had happened.

The neighbors supposed that the engagement with Col. Selby

had fallen through. Laura was ill for a long time, but she

recovered; she had that resolution in her that could conquer

death almost. And with her health came back her beauty,

and an added fascination, a something that might be mistaken

for sadness. Is there a beauty in the knowledge of evil, a

beauty that shines out in the face of a person whose inward

life is transformed by some terrible experience? Is the pathos

in the eyes of the Beatrice Cenci from her guilt or her

innocence?

Laura was not much changed. The lovely woman had a

devil in her heart. That was all.

| CHAPTER XVIII. The gilded age | ||