The gilded age a tale of to-day |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. | CHAPTER XV. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. |

| 30. |

| 31. |

| 32. |

| 33. |

| 34. |

| 35. |

| 36. |

| 37. |

| 38. |

| 39. |

| 40. |

| 41. |

| 42. |

| 43. |

| 44. |

| 45. |

| 46. |

| 47. |

| 48. |

| 49. |

| 50. |

| 51. |

| 52. |

| 53. |

| 54. |

| 55. |

| 56. |

| 57. |

| 58. |

| 59. |

| 60. |

| 61. |

| 62. |

| 63. |

| CHAPTER XV. The gilded age | ||

15. CHAPTER XV.

—Rationalem quidem puto medicinam esse debere: instrui vero ab evidentibus

causis, obscuris omnibus non à cogitatione artificis, sed ab ipsa arte rejectis.

Incidere autem vivorum corpora, et crudele, et supervacuum est: mortuorum

corpora discentibus necessarium.

Celsus.

ELI BOLTON and his wife talked over Ruth's case, as

they had often done before, with no little anxiety.

Alone of all their children she was impatient of the restraints

and monotony of the Friends' Society, and wholly indisposed

to accept the “inner light” as a guide into a life of acceptance

and inaction. When Margaret told her husband of

Ruth's newest project, he did not exhibit so much surprise as

she looked for. In fact he said that he did not see why a

woman should not enter the medical profession if she felt a

call to it.

“But,” said Margaret, “consider her total inexperience of

the world, and her frail health. Can such a slight little body

endure the ordeal of the preparation for, or the strain of, the

practice of the profession?”

“Did thee ever think, Margaret, whether she can endure

being thwarted in an object on which she has so set her heart,

as she has on this? Thee has trained her thyself at home, in

her enfeebled childhood, and thee knows how strong her will

is, and what she has been able to accomplish in self-culture by

the simple force of her determination. She never will be

satisfied until she has tried her own strength.”

“I wish,” said Margaret, with an inconsequence that is not

exclusively feminine, “that she were in the way to fall in

love and marry by and by. I think that would cure her of

some distant school, into an entirely new life, her thoughts

would be diverted.”

Eli Bolton almost laughed as he regarded his wife, with

eyes that never looked at her except fondly, and replied,

“Perhaps thee remembers that thee had notions also, before

we were married, and before thee became a member of

Meeting. I think Ruth comes honestly by certain tendencies

which thee has hidden under the Friend's dress.”

Margaret could not say no to this, and while she paused, it

was evident that memory was busy with suggestions to shake

her present opinions.

“Why not let Ruth try the study for a time,” suggested

Eli; “there is a fair beginning of a Woman's Medical College

in the city. Quite likely she will soon find that she needs

first a more general culture, and fall in with thy wish that

she should see more of the world at some large school.”

There really seemed to be nothing else to be done, and

Margaret consented at length without approving. And it was

agreed that Ruth, in order to spare her fatigue, should take

lodgings with friends near the college and make a trial in the

pursuit of that science to which we all owe our lives, and

sometimes as by a miracle of escape.

That day Mr. Bolton brought home a stranger to dinner,

Mr. Bigler of the great firm of Pennybacker, Bigler & Small,

railroad contractors. He was always bringing home somebody,

who had a scheme; to build a road, or open a mine, or

plant a swamp with cane to grow paper-stock, or found a

hospital, or invest in a patent shad-bone separator, or start a

college somewhere on the frontier, contiguous to a land

speculation.

The Bolton house was a sort of hotel for this kind of people.

They were always coming. Ruth had known them from

childhood, and she used to say that her father attracted them

as naturally as a sugar hogshead does flies. Ruth had an idea

that a large portion of the world lived by getting the rest of

the world into schemes. Mr. Bolton never could say “no”

to any of them, not even, said Ruth again, to the society for

stamping oyster shells with scripture texts before they were

sold at retail.

Mr. Bigler's plan this time, about which he talked

loudly, with his mouth full, all dinner time, was the building

of the Tunkhannock, Rattlesnake and Youngwomanstown

railroad, which would not only be a great highway to

the west, but would open to market inexhaustible coal-fields

and untold millions of lumber. The plan of operations

was very simple.

“We'll buy the lands,” explained he, “on long time, backed

by the notes of good men; and then mortgage them for

money enough to get the road well on. Then get the towns

on the line to issue their bonds for stock, and sell their bonds

for enough to complete the road, and partly stock it, especially

if we mortgage each section as we complete it. We can then

sell the rest of the stock on the prospect of the business of

the road through an improved country, and also sell the lands

at a big advance, on the strength of the road. All we want,”

continued Mr. Bigler in his frank manner, “is a few thousand

dollars to start the surveys, and arrange things in the legislature.

There is some parties will have to be seen, who might

make us trouble.”

“It will take a good deal of money to start the enterprise,”

remarked Mr. Bolton, who knew very well what “seeing” a

Pennsylvania Legislature meant, but was too polite to tell Mr.

Bigler what he thought of him, while he was his guest; “what

security would one have for it?”

Mr. Bigler smiled a hard kind of smile, and said, “You'd

be inside, Mr. Bolton, and you'd have the first chance in

the deal.”

This was rather unintelligible to Ruth, who was nevertheless

somewhat amused by the study of a type of character she had

seen before. At length she interrupted the conversation by

asking,

“You'd sell the stock, I suppose, Mr. Bigler, to anybody

who was attracted by the prospectus?”

“O, certainly, serve all alike,” said Mr. Bigler, now noticing

Ruth for the first time, and a little puzzled by the serene,

intelligent face that was turned towards him.

“Well, what would become of the poor people who had

been led to put their little money into the speculation, when

you got out of it and left it half way?”

It would be no more true to say of Mr. Bigler that he was

or could be embarrassed, than to say that a brass counterfeit

dollar-piece would change color when refused; the question

annoyed him a little, in Mr. Bolton's presence.

“Why, yes, Miss, of course, in a great enterprise for the

benefit of the community there will little things occur, which,

which—and, of course, the poor ought to be looked to; I tell

my wife, that the poor must be looked to; if you can tell

who are poor—there's so many impostors. And then, there's

contractor with a sort of a chuckle, “isn't that so, Mr.

Bolton?”

Eli Bolton replied that he never had much to do with the

legislature.

“Yes,” continued this public benefactor, “an uncommon

poor lot this year, uncommon. Consequently an expensive

lot. The fact is, Mr. Bolton, that the price is raised so high

on United States Senator now, that it affects the whole market;

you can't get any public improvement through on

reasonable terms. Simony is what I call it, Simony,” repeated

Mr. Bigler, as if he had said a good thing.

Mr. Bigler went on and gave some very interesting details

of the intimate connection between railroads and politics, and

thoroughly entertained himself all dinner time, and as much

disgusted Ruth, who asked no more questions, and her father

who replied in monosyllables.

“I wish,” said Ruth to her father, after the guest had

gone, “that you wouldn't bring home any more such horrid

men. Do all men who wear big diamond breast-pins, flourish

their knives at table, and use bad grammar, and cheat?”

“O, child, thee mustn't be too observing. Mr. Bigler is

one of the most important men in the state; nobody has

more influence at Harrisburg. I don't like him any more

than thee does, but I'd better lend him a little money than

to have his ill will.”

“Father, I think thee'd better have his ill-will than his

company. Is it true that he gave money to help build the

pretty little church of St. James the Less, and that he is one

of the vestrymen?”

“Yes. He is not such a bad fellow. One of the men in

Third street asked him the other day, whether his was a high

church or a low church? Bigler said he didn't know; he'd

been in it once, and he could touch the ceiling in the side

aisle with his hand.”

“I think he's just horrid,” was Ruth's final summary of

him, after the manner of the swift judgment of women, with

Bigler had no idea that he had not made a good impression

on the whole family; he certainly intended to be agreeable.

Margaret agreed with her daughter, and though she never

said anything to such people, she was grateful to Ruth for

sticking at least one pin into him.

Such was the serenity of the Bolton household that a stranger

in it would never have suspected there was any opposition

to Ruth's going to the Medical School. And she went

quietly to take her residence in town, and began her attendance

of the lectures, as if it were the most natural thing in

the world. She did not heed, if she heard, the busy and

wondering gossip of relations and acquaintances, gossip that

has no less currency among the Friends than elsewhere

because it is whispered slyly and creeps about in an undertone.

Ruth was absorbed, and for the first time in her life

thoroughly happy; happy in the freedom of her life, and in

the keen enjoyment of the investigation that broadened its

field day by day. She was in high spirits when she came

home to spend First Days; the house was full of her gaiety

and her merry laugh, and the children wished that Ruth

would never go away again. But her mother noticed, with

a little anxiety, the sometimes flushed face, and the sign of

an eager spirit in the kindling eyes, and, as well, the serious

air of determination and endurance in her face at unguarded

moments.

The college was a small one and it sustained itself not

without difficulty in this city, which is so conservative, and is

yet the origin of so many radical movements. There were

not more than a dozen attendants on the lectures all together,

so that the enterprise had the air of an experiment, and the

fascination of pioneering for those engaged in it. There was

one woman physician driving about town in her carriage,

attacking the most violent diseases in all quarters with persistent

courage, like a modern Bellona in her war chariot,

who was popularly supposed to gather in fees to the amount

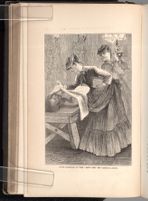

ANATOMICAL INVESTIGATIONS.

[Description: 499EAF. Page 145. In-line image of two women sitting at a desk working on dissections in a medical room with skeletons in the backroom.] of ten to twenty thousand dollars a year. Perhaps some ofthese students looked forward to the near day when they

would support such a practice and a husband besides, but it is

unknown that any of them ever went further than practice in

hospitals and in their own nurseries, and it is feared that some

of them were quite as ready as their sisters, in emergencies,

to “call a man.”

If Ruth had any exaggerated expectations of a professional

life, she kept them to herself, and was known to her fellows

of the class simply as a cheerful, sincere student, eager in her

investigations, and never impatient at anything, except an

insinuation that women had not as much mental capacity for

science as men.

They really say,” said one young Quaker sprig to another

youth of his age, “that Ruth Bolton is really going to be a

saw-bones, attends lectures, cuts up bodies, and all that. She's

cool enough for a surgeon, anyway.” He spoke feelingly,

for he had very likely been weighed in Ruth's calm eyes

accompanied a puzzling reply to one of his conversational

nothings. Such young gentlemen, at this time, did not come

very distinctly into Ruth's horizon, except as amusing circumstances.

About the details of her student life, Ruth said very little

to her friends, but they had reason to know, afterwards, that

it required all her nerve and the almost complete exhaustion

of her physical strength, to carry her through. She began

her anatomical practice upon detached portions of the human

frame, which were brought into the demonstrating room—

dissecting the eye, the ear, and a small tangle of muscles

and nerves—an occupation which had not much more savor

of death in it than the analysis of a portion of a plant out of

which the life went when it was plucked up by the roots.

Custom inures the most sensitive persons to that which is at

first most repellant; and in the late war we saw the most

delicate women, who could not at home endure the sight of

blood, become so used to scenes of carnage, that they walked

the hospitals and the margins of battle-fields, amid the poor

remnants of torn humanity, with as perfect self-possession

as if they were strolling in a flower garden.

It happened that Ruth was one evening deep in a line of

investigation which she could not finish or understand without

demonstration, and so eager was she in it, that it seemed

as if she could not wait till the next day. She, therefore,

persuaded a fellow student, who was reading that evening

with her, to go down to the dissecting room of the college,

and ascertain what they wanted to know by an hour's work

there. Perhaps, also, Ruth wanted to test her own nerve,

and to see whether the power of association was stronger in

her mind than her own will.

The janitor of the shabby and comfortless old building

admitted the girls, not without suspicion, and gave them

lighted candles, which they would need, without other remark

than “there's a new one, Miss,” as the girls went up the

broad stairs.

They climbed to the third story, and paused before a door,

apartment, with a row of windows on one side and one at the

end. The room was without light, save from the stars and

the candles the girls carried, which revealed to them dimly

two long and several small tables, a few benches and chairs,

a couple of skeletons hanging on the wall, a sink, and cloth-covered

heaps of something upon the tables here and there.

The windows were open, and the cool night wind came in

strong enough to flutter a white covering now and then, and

to shake the loose casements. But all the sweet odors of the

night could not take from the room a faint suggestion of

mortality.

The young ladies paused a moment. The room itself was

familiar enough, but night makes almost any chamber eerie,

and especially such a room of detention as this where the

mortal parts of the unburied might almost be supposed to be

visited, on the sighing night winds, by the wandering spirits

of their late tenants.

Opposite and at some distance across the roofs of lower

buildings, the girls saw a tall edifice, the long upper story

of which seemed to be a dancing hall. The windows of that

were also open, and through them they heard the scream of

the jiggered and tortured violin, and the pump, pump of the

oboe, and saw the moving shapes of men and women in quick

transition, and heard the prompter's drawl.

“I wonder,” said Ruth, “what the girls dancing there

would think if they saw us, or knew that there was such a

room as this so near them.”

She did not speak very loud, and, perhaps unconsciously,

the girls drew near to each other as they approached the long

table in the centre of the room. A straight object lay upon

it, covered with a sheet. This was doubtless “the new one”

of which the janitor spoke. Ruth advanced, and with a not

very steady hand lifted the white covering from the upper

part of the figure and turned it down. Both the girls started.

It was a negro. The black face seemed to defy the pallor of

death, and asserted an ugly life-likeness that was frightful.

“Come away, Ruth, it is awful.”

Perhaps it was the wavering light of the candles, perhaps

it was only the agony from a death of pain, but the repulsive

black face seemed to wear a scowl that said, “Haven't you

yet done with the outcast, persecuted black man, but you must

now haul him from his grave, and send even your women to

dismember his body?”

Who is this dead man, one of thousands who died yesterday,

and will be dust anon, to protest that science shall not

turn his worthless carcass to some account?

Ruth could have had no such thought, for with a pity in

her sweet face, that for the moment overcame fear and disgust,

she reverently replaced the covering, and went away to

her own table, as her companion did to hers. And there for

an hour they worked at their several problems, without

speaking, but not without an awe of the presence there, “the

new one,” and not without an awful sense of life itself, as

they heard the pulsations of the music and the light laughter

from the dancing-hall.

When, at length, they went away, and locked the dreadful

room behind them, and came out into the street, where people

were passing, they, for the first time, realized, in the relief

they felt, what a nervous strain they had been under.

| CHAPTER XV. The gilded age | ||