We and our neighbors, or, The records of an

unfashionable street (Sequel to 'My wife and I.") : a novel |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. |

| 30. |

| 31. |

| 32. |

| 33. |

| 34. |

| 35. |

| 36. | CHAPTER XXXVI.

LOVE IN CHRISTMAS GREENS. |

| 37. |

| 38. |

| 39. |

| 40. |

| 41. |

| 42. |

| 43. |

| 44. |

| 45. |

| 46. |

| 47. |

| 48. |

| 49. |

| 50. |

| 51. |

| 52. |

| 53. |

| 54. |

| CHAPTER XXXVI.

LOVE IN CHRISTMAS GREENS. We and our neighbors, or, The records of an

unfashionable street | ||

36. CHAPTER XXXVI.

LOVE IN CHRISTMAS GREENS.

THE little chapel in one of the out-of-the-way streets

of New York presented a scene of Christmas activity

and cheerfulness approaching to gaiety. The whole

place was fragrant with the spicy smell of spruce and

hemlock. Baskets of green ruffles of ground-pine were

foaming over their sides with abundant contributions

from the forest; and bright bunches of vermilion bitter-sweet,

and the crimson-studded branches of the black

alder, added color to the picture. Of real traditional

holly, which in America is a rarity, there was a scant

supply, reserved for more honorable decorations.

Mr. St. John had been busy in his vestry with paper,

colors, and gilding, illuminating some cards with Scriptural

mottoes. He had just brought forth his last effort

and placed it in a favorable light for inspection. It is the

ill-fortune of every successful young clergyman to stir

the sympathies and enkindle the venerative faculties of

certain excitable women, old and young, who follow his

footsteps and regard his works and ways with a sort of

adoring rapture that sometimes exposes him to ridicule

if he accepts it, and which yet it seems churlish to

decline. It is not generally his fault, nor exactly the

fault of the women, often amiably sincere and unconscious;

but it is a fact that this kind of besetment is

more or less the lot of every clergyman, and he cannot

help it. It is to be accepted as we accept any of the

shadows which are necessary in the picture of life, and

got along with by the kind of common sense with which

we dispose of any of its infelicities.

Mr. St. John did little to excite demonstrations of

this kind; but the very severity with which he held himself

in reserve seemed rather to increase a kind of sacred

prestige which hung around him, making of him a sort

of churchly Grand Llama. When, therefore, he brought

out his illuminated card, on which were inscribed in

Anglo Saxon characters,

And dwelt among us,”

with groans of intense admiration from Miss Augusta

Gusher and Miss Sophronia Vapors, which was echoed

in “ohs!” and “ahs!” from an impressible group of girls

on the right and left.

Angelique stood quietly gazing on it, with a wreath

of ground-pine dangling from her hand, but she said

nothing.

Mr. St. John at last said, “And what do you think,

Miss Van Arsdel?”

“I think the colors are pretty,” Angie said, hesitating,

“but”—

“But what?” said Mr. St. John, quickly.

“Well, I don't know what it means—I don't understand

it.”

Mr. St. John immediately read the inscription in

concert with Miss Gusher, who was a very mediæval

young lady and quite up to reading Gothic, or Anglo

Saxon, or Latin, or any Churchly tongue.

“Oh!” was all the answer Angie made; and then,

seeing something more was expected, she added again,

“I think the effect of the lettering very pretty,” and

turned away, and busied herself with a cross of ground-pine

that she was making in a retired corner.

The chorus were loud and continuous in their ac

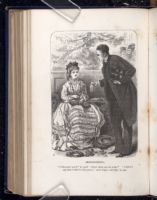

SKIRMISHING.

"I like your work," he said, "better than you do mine." "I did n't

say that I did n't like yours." said Angie, coloring.—p. 341.

[Description: 710EAF. Illustration page. Image of a woamn seated and a man standing. The woman has floral wreaths scattered around her feet. The man has his top had in one hand, and with the other is handing the woman an object, possibly a white glove. In the background

two women are frowing and watching the man and woman.]

inscriptions in Greek and Latin, offering to illuminate

some of them for the occasion. Mr. St. John thanked

her and withdrew to his sanctum, less satisfied than

before.

About half an hour after, Angie, who was still quietly

busy upon her cross in her quiet corner, under the shade

of a large hemlock tree which had been erected there,

was surprised to find Mr. St. John standing, silently

observing her work.

“I like your work,” he said, “better than you did

mine.”

“I didn't say that I didn't like yours,” said Angie,

coloring, and with that sort of bright, quick movement

that gave her the air of a bird just going to fly.

“No, you did not say, but you left approbation unsaid,

which amounts to the same thing. You have some

objection, I see, and I really wish you would tell me

frankly what it is.”

“O Mr. St. John, don't say that! Of course I

never thought of objecting; it would be presumptuous

in me. I really don't understand these matters at all,

not at all. I just don't know anything about Gothic

letters and all that, and so the card doesn't say anything

to me. And I must confess, I thought”—

Here Angie, like a properly behaved young daughter

of the Church, began to perceive that her very next sentence

might lead her into something like a criticism

upon her rector; and she paused on the brink of a gulf

so horrible, “with pious awe that feared to have offended.”

Mr. St. John felt a very novel and singular pleasure

in the progress of this interview. It interested him to

be differed with, and he said, with a slight intonation of

dictation:

“I must insist on your telling me what you thought,

Miss Angie.”

“Oh, nothing, only this—that if I, who have had

more education than our Sunday-school scholars, can't

read a card like that, why, they could not. I'm quite

sure that an inscription in plain modern letters that I

could read would have more effect upon my mind, and I

am quite sure it would on them.”

“I thank you sincerely for your frankness, Miss

Angie; your suggestion is a valuable one.”

“I think,” said Angie, “that mediæval inscriptions,

and Greek and Latin mottoes, are interesting to educated,

cultivated people. The very fact of their being

in another language gives a sort of piquancy to them.

The idea gets a new coloring from a new language; but

to people who absolutely don't understand a word, they

say nothing, and of course they do no good; so, at least,

it seems to me.”

“You are quite right, Miss Angie, and I shall immediately

put my inscription into the English of to-day.

The fact is, Miss Angie,” added St. John after a silent

pause, “I feel more and more what a misfortune it has

been to me that I never had a sister. There are so many

things where a woman's mind sees so much more clearly

than a man's. I never had any intimate female friend.”

Here Mr. St. John began assiduously tying up little

bunches of the ground-pine in the form which Angie

needed for her cross, and laying them for her.

Now, if Angie had been a sophisticated young lady,

familiar with the tactics of flirtation, she might have had

precisely the proper thing at hand to answer this remark;

as it was, she kept on tying her bunches assiduously and

feeling a little embarrassed.

It was a pity he should not have a sister, she thought.

Poor man, it must be lonesome for him; and Angie's

or some emotion that emboldened the young

man to say, in a lower tone, as he laid down a bunch of

green by her:

“If you, Miss Angie, would look on me as you do on

your brothers, and tell me sincerely your opinion of me,

it might be a great help to me.”

Now Mr. St. John was certainly as innocent and

translucently ignorant of life as Adam at the first hour

of his creation, not to know that the tone in which he

was speaking and the impulse from which he spoke, at

that moment, was in fact that of man's deepest, most

absorbing feeling towards woman. He had made his

scheme of life; and, as a set purpose, had left love out

of it, as something too terrestrial and mundane to consist

with the sacred vocation of a priest. But, from the

time he first came within the sphere of Angelique, a

strange, delicious atmosphere, vague and dreamy, yet

delightful, had encircled him, and so perplexed and dizzied

his brain as to cause all sorts of strange vibrations.

At first, there was a sort of repulsion—a vague alarm, a

suspicion and repulsion singularly blended with an

attraction. He strove to disapprove of her; he resolved

not to think of her; he resolutely turned his head away

from looking at her in her place in Sunday-school and

church, because he felt that his thoughts were alarmingly

drawn in that direction.

Then came his invitation into society, of which the

hidden charm, unacknowledged to himself, was that he

should meet Angelique; and that mingling in society had

produced, inevitably, modifying effects, which made him

quite a different being from what he was in his recluse

life passed between the study and the altar.

It is not in man, certainly not in a man so finely

fibered and strung as St. John, to associate intimately

and finding many things in himself of which he had

not dreamed.

But if there be in the circle some one female presence

which all the while is sending out an indefinite though

powerful enchantment, the developing force is still more

marked.

St. John had never suspected himself of the ability

to be so agreeable as he found himself in the constant

reunions which, for one cause or another, were taking

place in the little Henderson house. He developed a

talent for conversation, a vein of gentle humor, a turn

for versification, with a cast of thought rising into the

sphere of poetry, and then, with Dr. Campbell and Alice

and Angie, he formed no mean quartette in singing.

In all these ways he had been coming nearer and

nearer to Angie, without taking the alarm. He remembered

appositely what Montalembert in his history of the

monks of the Middle Ages says of the female friendships

which always exerted such a modifying power in the lives

of celebrated saints; how St. Jerome had his Eudochia,

and St. Somebody-else had a sister, and so on. And as

he saw more and more of Angelique's character, and felt

her practical efficiency in church work, he thought it

would be very lovely to have such a friend all to himself.

Now, friendship on the part of a young man of twenty-five

for a young saint with hazel eyes and golden hair,

with white, twinkling hands and a sweet voice, and an

assemblage of varying glances, dimples and blushes, is

certainly a most interesting and delightful relation; and

Mr. St. John built it up and adorned it with all sorts of

charming allegories and figures and images, making a

sort of semi-celestial affair of it.

It is true, he had given up St. Jerome's love, and

concluded that it was not necessary that his “heart's

a dying altar-fire; he had learned to admire Angie's

blooming color and elastic step, and even to take an appreciative

delight in the prettinesses of her toilette; and,

one evening, when she dropped a knot of peach-blow

ribbons from her bosom, the young divine had most

unscrupulously appropriated the same, and, taking it

home, gloated over it as a holy relic, and yet he never

suspected that he was in love—oh, no! And, at this

moment, when his voice was vibrating with that strange

revealing power that voices sometimes have in moments

of emotion, when the very tone is more than the words,

he, poor fellow, was ignorant that his voice had said to

Angie, “I love you with all my heart and soul.”

But there is no girl so uninstructed and so inexperienced

as not to be able to interpret a tone like this at

once, and Angie at this moment felt a sort of bewildering

astonishment at the revelation. All seemed to go

round and round in dizzy mazes—the greens, the red

berries—she seemed to herself to be walking in a dream,

and Mr. St. John with her.

She looked up and their eyes met, and at that

moment the veil fell from between them. His great,

deep, blue eyes had in them an expression that could

not be mistaken.

“Oh, Mr. St. John!” she said.

“Call me Arthur,” he said, entreatingly.

“Arthur!” she said, still as in a dream.

“And may I call you Angelique, my good angel, my

guide? Say so!” he added, in a rapid, earnest whisper,

“say so, dear, dearest Angie!”

“Yes, Arthur,” she said, still wondering.

“And, oh, love me,” he added, in a whisper; “a

little, ever so little! You cannot think how precious it

will be to me!”

“Mr. St. John!” called the voice of Miss Gusher.

He started in a guilty way, and came out from behind

the thick shadows of the evergreen which had concealed

this little tête-à-tête. He was all of a sudden

transformed to Mr. St. John, the rector—distant, cold,

reserved, and the least bit in the world dictatorial. In

his secret heart, Mr. St. John did not like Miss Gusher.

It was a thing for which he condemned himself, for she

was a most zealous and efficient daughter of the Church.

She had worked and presented a most elegant set of

altar-cloths, and had made known to him her readiness

to join a sisterhood whenever he was ready to ordain

one. And she always admired him, always agreed with

him, and never criticised him, which perverse little

Angie sometimes did; and yet ungrateful Mr. St. John

was wicked enough at this moment to wish Miss Gusher

at the bottom of the Red Sea, or in any other Scriptural

situation whence there would be no probability of her

getting at him for a season.

“I wanted you to decide on this decoration for the

font,” she said. “Now, there is this green wreath and

this red cross of bitter-sweet. To be sure, there is no

tradition about bitter-sweet; but the very name is symbolical,

and I thought that I would fill the font with

calla lilies. Would lilies at Christmas be strictly

Churchly? That is my only doubt. I have always seen

them appropriated to Easter. What should you say, Mr.

St. John?”

“Oh, have them by all means, if you can,” said Mr.

St. John. “Christmas is one of the Church's highest

festivals, and I admit anything that will make it beautiful.”

Mr. St. John said this with a radiancy of delight

which Miss Gusher ascribed entirely to his approbation

of her zeal; but the heavens and the earth had assumed

For when Angie lifted her eyes, not only had she read

the unutterable in his, but he also had looked far down

into the depths of her soul, and seen something he did not

quite dare to put into words, but in the light of which his

whole life now seemed transfigured.

It was a new and amazing experience to Mr. St. John,

and he felt strangely happy, yet particularly anxious that

Miss Gusher and Miss Vapors, and all the other tribe

of his devoted disciples, should not by any means suspect

what had fallen out; and therefore it was that he

assumed such a cheerful zeal in the matter of the font

and decorations.

Meanwhile, Angie sat in her quiet corner, like a good

little church mouse, working steadily and busily on her

cross. Just as she had put in the last bunch of bitter-sweet,

Mr. St. John was again at her elbow.

“Angie,” he said, “you are going to give me that

cross. I want it for my study, to remember this morning

by.”

“But I made it for the front of the organ.”

“Never mind. I can put another there; but this is

to be mine,” he said, with a voice of appropriation. “I

want it because you were making it when you promised

what you did. You must keep to that promise, Angie.”

“Oh, yes, I shall.”

“And I want one thing more,” he said, lifting Angie's

little glove, where it had fallen among the refuse

pieces.

“What!—my glove? Is not that silly?”

“No, indeed.”

“But my hands will be cold.”

“Oh, you have your muff. See here: I want it,” he

said, “because it seems so much like you, and you don't

know how lonesome I feel sometimes.”

Poor man! Angie thought, and she let him have the

glove. “Oh,” she said, apprehensively, “please don't

stay here now. I hear Miss Gusher calling for you.”

“She is always so busy,” said he, in a tone of discontent.

“She is so good,” said Angie, “and does so much.”

“Oh, yes, good enough,” he said, in a discontented

tone, retreating backward into the shadow of the hemlock,

and so finding his way round into the body of the

church.

But there is no darkness or shadow of death where a

handsome, engaging young rector can hide himself so

that the truth about him will not get into the bill of some

bird of the air.

The sparrows of the sanctuary are many, and they are

particularly wide awake and watchful.

Miss Gusher had been witness of this last little bit of

interview; and, being a woman of mature experience,

versed in the ways of the world, had seen, as she said,

through the whole matter.

“Mr. St. John is just like all the rest of them, my

dear,” she said to Miss Vapors, “he will flirt, if a girl

will only let him. I saw him just now with that Angie

Van Arsdel. Those Van Arsdel girls are famous for

drawing in any man they happen to associate with.”

“You don't say so,” said Miss Vapors; “what did

you see?”

“Oh, my dear, I sha'n't tell; of course, I don't approve

of such things, and it lowers Mr. St. John in my

esteem,—so I'd rather not speak of it. I did hope he

was above such things.”

“But do tell me, did he say anything?” said Miss

Vapors, ready to burst in ignorance.

“Oh, no. I only saw some appearances and expressions—a

certain manner between them that told all.

going on between Angie Van Arsdel and Mr. St.

John. I don't see, for my part, what it is in those Van

Arsdel girls that the men see; but, sure as one of them

is around, there is a flirtation got up.”

“Why, they're not so very beautiful,” said Miss

Vapors.

“Oh, dear, no. I never thought them even pretty;

but then, you see, there's no accounting for those things.”

And so, while Mr. St. John and Angie were each wondering

secretly over the amazing world of mutual understanding

that had grown up between them, the rumor

was spreading and growing in all the band of Christian

workers.

| CHAPTER XXXVI.

LOVE IN CHRISTMAS GREENS. We and our neighbors, or, The records of an

unfashionable street | ||