We and our neighbors, or, The records of an

unfashionable street (Sequel to 'My wife and I.") : a novel |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. |

| 30. |

| 31. |

| 32. |

| 33. |

| 34. | CHAPTER XXXIV.

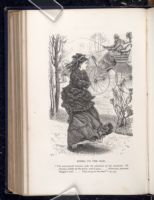

GOING TO THE BAD. |

| 35. |

| 36. |

| 37. |

| 38. |

| 39. |

| 40. |

| 41. |

| 42. |

| 43. |

| 44. |

| 45. |

| 46. |

| 47. |

| 48. |

| 49. |

| 50. |

| 51. |

| 52. |

| 53. |

| 54. |

| CHAPTER XXXIV.

GOING TO THE BAD. We and our neighbors, or, The records of an

unfashionable street | ||

34. CHAPTER XXXIV.

GOING TO THE BAD.

IT was the week before Christmas, and all New York

was stirring and rustling with a note of preparation.

Every shop and store was being garnished and furbished

to look its best. Christmas-trees for sale lay at the doors

of groceries; wreaths of ground-pine, and sprigs and

branches of holly, were on sale, and selling briskly.

Garlands and anchors and crosses of green began to

adorn the windows of houses, and were a merchantable

article in the stores. The toy-shops were flaming and

flaunting with a delirious variety of attractions, and

mammas and papas with puzzled faces were crowding

and jostling each other, and turning anxiously from side

to side in the suffocating throng that crowded to the

counters, while the shopmen were too flustered to answer

questions, and so busy that it seemed a miracle

when anybody got any attention. The country-folk

were pouring into New York to do Christmas shopping,

and every imaginable kind of shop had in its window

some label or advertisement or suggestion of something

that might answer for a Christmas gift. Even the grim,

heavy hardware trade blossomed out into festal suggestions.

Tempting rows of knives and scissors glittered

in the windows; little chests of tools for little masters,

with cards and labels to call the attention of papa to the

usefulness of the present. The confectioners' windows

were a glittering mass of sugar frostwork of every fanciful

device, gay boxes of bonbons, marvelous fabrications of

device; and bewildered crowds of well-dressed purchasers

came and saw and bought faster than the two hands

of the shopmen could tie up and present the parcels.

The grocery stores hung out every possible suggestion

of festal cheer. Long strings of turkeys and chickens,

green bunches of celery, red masses of cranberries,

boxes of raisins and drums of figs, artistically arranged,

and garnished with Christmas greens, addressed themselves

eloquently to the appetite, and suggested that the

season of festivity was at hand.

The weather was stinging cold—cold enough to nip

one's toes and fingers, as one pressed round, doing

Christmas shopping, and to give cheeks and nose alike

a tinge of red. But nobody seemed to mind the cold.

“Cold as Christmas” has become a cheery proverb; and

for prosperous, well-living people, with cellars full of

coal, with bright fires and roaring furnaces and well-tended

ranges, a cold Christmas is merely one of the

luxuries. Cold is the condiment of the season; the

stinging, smarting sensation is an appetizing reminder of

how warm and prosperous and comfortable are all within

doors.

But did any one ever walk the streets of New York,

the week before Christmas, and try to imagine himself

moving in all this crowd of gaiety, outcast, forsaken and

penniless? How dismal a thing is a crowd in which you

look in vain for one face that you know! how depressing

the sense that all this hilarity and abundance and

plenty is not for you! Shakespeare has said, “How

miserable it is to look into happiness through another

man's eyes—to see that which you might enjoy and may

not, to move in a world of gaiety and prosperity where

there is nothing for you!”

Such were Maggie's thoughts, the day she went out

herself once more upon the world. Poor hot-hearted,

imprudent child, why did she run from her only friends?

Well, to answer that question, we must think a little. It

is a sad truth, that when people have taken a certain

number of steps in wrong-doing, even the good that is in

them seems to turn against them and become their

enemy. It was in fact a residuum of honor and generosity,

united with wounded pride, that drove Maggie

into the street, that morning. She had overheard the

conversation between Aunt Maria and Eva; and certain

parts of it brought back to her mind the severe reproaches

which had fallen upon her from her Uncle

Mike. He had told her she was a disgrace to any honest

house, and she had overheard Aunt Maria telling the

same thing to Eva,—that the having and keeping such

as she in her home was a disreputable, disgraceful thing,

and one that would expose her to very unpleasant comments

and observations. Then she listened to Aunt

Maria's argument, to show Eva that she had better send

her mother away and take another woman in her place,

because she was encumbered with such a daughter.

“Well,” she said to herself, “I'll go then. I'm in

everybody's way, and I get everybody into trouble that's

good to me. I'll just take myself off. So there!” and

Maggie put on her things and plunged into the street

and walked very fast in a tumult of feeling.

She had a few dollars in her purse that her mother

had given her to buy winter clothing; enough, she

thought vaguely, to get her a few days' lodging somewhere,

and she would find something honest to do.

Maggie knew there were places where she would be

welcomed with an evil welcome, where she would have

praise and flattery instead of chiding and rebuke; but

she did not intend to go to them just yet.

The gentle words that Eva had spoken to her, the

hope and confidence she had expressed that she might

yet retrieve her future, were a secret cord that held her

back from going to the utterly bad.

The idea that somebody thought well of her, that

somebody believed in her, and that a lady pretty, graceful,

and admired in the world, seemed really to care to

have her do well, was a redeeming thought. She would

go and get some place, and do something for herself,

and when she had shown that she could do something,

she would once more make herself known to her friends.

Maggie had a good gift at millinery, and, at certain odd

times, had worked in a little shop on Sixteenth Street,

where the mistress had thought well of her, and made

her advantageous offers. Thither she went first, and

asked to see Miss Pinhurst. The moment, however,

that she found herself in that lady's presence, she was

sorry she had come. Evidently, her story had preceded

her. Miss Pinhurst had heard all the particulars of her

ill conduct, and was ready to the best of her ability to

act the part of the flaming sword that turned every way

to keep the fallen Eve out of paradise.

“I am astonished, Maggie, that you should even

think of such a thing as getting a place here, after all's

come and gone that you know of; I am astonished that

you could for one moment think of it. None but young

ladies of good character can be received into our work-rooms.

If I should let such as you come in, my respectable

girls would feel insulted. I don't know but they

would leave in a body. I think I should leave, under

the same circumstances. No, I wish you well, Maggie,

and hope that you may be brought to repentance; but,

as to the shop, it isn't to be thought of.”

Now, Miss Pinhurst was not a hard-hearted woman;

not, in any sense, a cruel woman; she was only on that

part of society keeps off the ill-behaving. Society has

its instincts of self-protection and self-preservation, and

seems to order the separation of the sheep and the goats,

even before the time of final judgment. For, as a general

thing, it would not be safe and proper to admit

fallen women back into the ranks of those unfallen,

without some certificate of purgation. Somebody must

be responsible for them, that they will not return again

to bad ways, and draw with them the innocent and inexperienced.

Miss Pinhurst was right in requiring an

unblemished record of moral character among her shop-girls.

It was her mission to run a shop and run it well;

it was not her call to conduct a Magdalen Asylum:

hence, though we pity poor Maggie, coming out into the

cold with the bitter tears of rejection freezing her cheek,

we can hardly blame Miss Pinhurst. She had on her

hands already all that she could manage.

Besides, how could she know that Maggie was really

repentant? Such creatures were so artful; and, for

aught she knew, she might be coming for nothing else

than to lure away some of her girls, and get them into

mischief. She spoke the honest truth, when she said she

wished well to Maggie. She did wish her well. She

would have been sincerely glad to know that she had

gotten into better ways, but she did not feel that it was

her business to undertake her case. She had neither

time nor skill for the delicate and difficult business of

reformation. Her helpers must come to her ready-made,

in good order, and able to keep step and time: she

could not be expected to make them over.

“How hard they all make it to do right!” thought

Maggie. But she was too proud to plead or entreat.

“They all act as if I had the plague, and should give it

to them; and yet I don't want to be bad. I'd a great

way. Nobody will have me, or let me stay,” and Maggie

felt a sobbing pity for herself. Why should she be

treated as if she were the very off-scouring of the earth,

when the man who had led her into all this sin and sorrow

was moving in the best society, caressed, admired,

flattered, married to a good, pious, lovely woman, and

carrying all the honors of life?

Why was it such a sin for her, and no sin for him?

Why could he repent and be forgiven, and why must

she never be forgiven? There was n't any justice in it,

Maggie hotly said to herself—and there was n't; and

then, as she walked those cold streets, pictures without

words were rising in her mind, of days when everybody

flattered and praised her, and he most of all. There is

no possession which brings such gratifying homage as

personal beauty; for it is homage more exclusively belonging

to the individual self than any other. The

tribute rendered to wealth, or talent, or genius, is far less

personal. A child or woman gifted with beauty has a

constant talisman that turns all things to gold—though,

alas! the gold too often turns out like fairy gifts; it is

gold only in seeming, and becomes dirt and slate-stone

on their hands.

Beauty is a dazzling and dizzying gift. It dazzles

first its possessor and inclines him to foolish action; and

it dazzles outsiders, and makes them say and do foolish

things.

From the time that Maggie was a little chit, running

in the street, people had stopped her, to admire her hair

and eyes, and talk all kinds of nonsense to her, for the

purpose of making her sparkle and flush and dimple,

just as one plays with a stick in the sparkling of a

brook. Her father, an idle, willful, careless creature,

made a show plaything of her, and spent his earnings for

too proud and fond; and it was no wonder that when

Maggie grew up to girlhood her head was a giddy one,

that she was self-willed, self-confident, obstinate. Maggie

loved ease and luxury. Who doesn't? If she had

been born on Fifth Avenue, of one of the magnates of

New York, it would have been all right, of course, for

her to love ribbons and laces and flowers and fine

clothes, to be imperious and self-willed, and to set her

pretty foot on the neck of the world. Many a young

American princess, gifted with youth and beauty and with

an indulgent papa and mamma, is no wiser than Maggie

was; but nobody thinks the worse of her. People laugh

at her little saucy airs and graces, and predict that she

will come all right by and by. But then, for her, beauty

means an advantageous marriage, a home of luxury and

a continuance through life of the petting and indulgence

which every one loves, whether wisely or not.

But Maggie was the daughter of a poor working-woman—an

Irishwoman at that—and what marriage leading

to wealth and luxury was in store for her?

To tell the truth, at seventeen, when her father died

and her mother was left penniless, Maggie was as unfit

to encounter the world as you, Miss Mary, or you, Miss

Alice, and she was a girl of precisely the same flesh and

blood as yourself. Maggie cordially hated everything

hard, unpleasant or disagreeable, just as you do. She

was as unused to crosses and self-denials as you are.

She longed for fine things and pretty things, for fine

sight-seeing and lively times, just as you do, and felt just

as you do that it was hard fate to be deprived of them.

But, when worse came to worst, she went to work with

Mrs. Maria Wouvermans. Maggie was parlor-girl and

waitress, and a good one too. She was ingenious, neat-handed,

quick and bright; and her beauty drew favorable

but only found fault. If Maggie carefully dusted every

one of the five hundred knick-knacks of the drawingroom

five hundred times, there was nothing said; but if,

on the five hundred and first time, a moulding or a crevice

was found with dust in it, Mrs. Wouvermans would

summon Maggie to her presence with the air of a judge,

point out the criminal fact, and inveigh, in terms of general

severity, against her carelessness, as if carelessness

were the rule rather than the exception.

Mrs. Wouvermans took special umbrage at Maggie's

dress—her hat, her feathers, her flowers—not because

they were ugly, but because they were pretty, a great

deal too pretty and dressy for her station. Mrs. Wouvermans's

ideal of a maid was a trim creature, content

with two gowns of coarse stuff and a bonnet devoid of

adornment; a creature who, having eyes, saw not anything

in the way of ornament or luxury; whose whole

soul was absorbed in work, for work's sake; content with

mean lodgings, mean furniture, poor food, and scanty

clothing; and devoting her whole powers of body and

soul to securing to others elegancies, comforts and luxuries

to which she never aspired. This self-denied sister

of charity, who stood as the ideal servant, Mrs. Wouvermans's

maid did not in the least resemble. Quite another

thing was the gay, dressy young lady who, on Sunday

mornings, stepped forth from the back gate of her

house with so much the air of a Murray Hill demoiselle

that people sometimes said to Mrs. Wouvermans, “Who

is that pretty young lady that you have staying with

you?”—a question that never failed to arouse a smothered

sense of indignation in that lady's mind, and added

bitterness to her reproofs and sarcasms, when she found

a picture-frame undusted, or pounced opportunely on a

cobweb in some neglected corner.

Maggie felt certain that Mrs. Wouvermans was on the

watch to find fault with her—that she wanted to condemn

her, for she had gone to service with the best of

resolutions. Her mother was poor and she meant to

help her; she meant to be a good girl, and, in her own

mind, she thought she was a very good girl to do so

much work, and remember so many different things in so

many different places, and forget so few things.

Maggie praised herself to herself, just as you do, my

young lady, when you have an energetic turn in household

matters, and arrange and beautify, and dust, and

adorn mamma's parlors, and then call on mamma and

papa and all the family to witness and applaud your

notability. At sixteen or seventeen, household virtue is

much helped in its development by praise. Praise is sunshine;

it warms, it inspires, it promotes growth: blame and

rebuke are rain and hail; they beat down and bedraggle,

even though they may at times be necessary. There

was a time in Maggie's life when a kind, judicious,

thoughtful, Christian woman might have kept her from

falling, might have won her confidence, become her

guide and teacher, and piloted her through the dangerous

shoals and quicksands which beset a bright, attractive,

handsome young girl, left to make her own way

alone and unprotected.

But it was not given to Aunt Maria to see this opportunity;

and, under her system of management, it was not

long before Maggie's temper grew fractious, and she used

to such purpose the democratic liberty of free speech,

which is the birthright of American servants, that Mrs.

Wouvermans never forgave her.

Maggie told her, in fact, that she was a hard-hearted,

mean, selfish woman, who wanted to get all she could

out of her servants, and to give the least she could in

return; and this came a little too near the truth ever to

out of the house, and went home to her mother, who

took her part with all her heart and soul, and declared

that Maggie shouldn't live out any longer—she should

be nobody's servant.

This, to be sure, was silly enough in Mary, since service

is the law of society, and we are all more or less

servants to somebody; but uneducated people never

philosophize or generalize, and so cannot help themselves

to wise conclusions.

All Mary knew was that Maggie had been scolded

and chafed by Mrs. Wouvermans; her handsome darling

had been abused, and she should get into some higher

place in the world; and so she put her as workwoman

into the fashionable store of S. S. & Co.

There Maggie was seen and coveted by the man who

made her his prey. Maggie was seventeen, pretty, silly,

hating work and trouble, longing for pleasure, leisure,

ease and luxury; and he promised them all. He told

her that she was too pretty to work, that if she would

trust herself to him she need have no more care; and

Maggie looked forward to a rich marriage and a home

of her own. To do her justice, she loved the man that

promised this with all the warmth of her Irish heart.

To her, he was the splendid prince in the fairy tale,

come to take her from poverty and set her among

princes; and she felt she could not do too much for him.

She would be such a good wife, she would be so devoted,

she would improve herself and learn so that she might

never discredit him.

Alas! in just such an enchanted garden of love, and

hope, and joy, how often has the ground caved in and

let the victim down into dungeons of despair that never

open!

Maggie thinks all this over as she pursues her cheer

GOING TO THE BAD.

"The sweet-faced woman calls the attention of her husband. He

frowns, whips up the horse, and is gone. . . Bitterness possisses

Maggie's soul. . . Why not go to the bad?"—p. 327.

[Description: 710EAF. Illustration page. Image of a woman walking and watching a carriage drive by with a man, woman, and child in it. It is windy and the womans skirts are blowing against her legs, her arms are crossed as if to warm herself. The people in the carriage are bundled in warm clothes.]

looks into face after face that has no pity for her.

Scarcely knowing why she did it, she took a car and

rode up to the Park, got out, and wandered drearily up

and down among the leafless paths from which all trace

of summer greenness had passed.

Suddenly, a carriage whirred past her. She looked

up. There he sat, driving, and by his side so sweet a

lady, and between them a flaxen-haired little beauty,

clasping a doll in her chubby arms!

The sweet-faced woman looks pitifully at the haggard,

weary face, and says something to call the attention

of her husband. An angry flush rises to his face. He

frowns, and whips up the horse, and is gone. A sort of

rage and bitterness possess Maggie's soul. What is the

use of trying to do better? Nobody pities her. Nobody

helps her. The world is all against her. Why not go

to the bad?

| CHAPTER XXXIV.

GOING TO THE BAD. We and our neighbors, or, The records of an

unfashionable street | ||