18. CHAPTER XVIII.

RAKING UP THE FIRE.

THE cream of an evening company is the latter end

of it, after the more ceremonious have slipped

away and only “we and our folks” remain to croon and

rake up the fire.

Mr. and Mrs. Van Arsdel, Angelique, and Marie

went home in the omnibus. Alice staid to spend the

night with Eva, and help put up the portfolios, and put

back the plants, and turn the bower back into a work-room,

and set up the vases of flowers in a cool place

where they could keep till morning; because, you know

—you who are versed in these things—that flowers in

December need to be made the most of, in order to go as

far as possible.

Bolton yet lingered in his arm-chair, in his favorite

corner, gazing placidly at the coals of the fire. Dr.

Campbell was solacing himself, after the unsatisfied longings

of the evening, with seeing how his own article

looked in print, and Jim Fellows was helping miscellaneously

in setting back flower-pots, re-arranging books,

and putting chairs and tables, that had been arranged

festively, back into humdrum household places. Meanwhile,

the kind of talk was going on that usually follows

a social venture—a sort of review of the whole scene and

of all the actors.

“Well, Doctor, what do you think of our rector?”

said Eva, tapping his magazine briskly.

He lowered his magazine and squared himself round

gravely.

“That fellow hasn't enough of the abdominal to

carry his brain power,” he said. “Splendid head—a little

too high in the upper stories and not quite heavy

enough in the basement. But if he had a good broad,

square chest, and a good digestive and blood-making

apparatus, he'd go. The fellow wants blood; he needs

mutton and beef, and plenty of it. That's what he

needs. What's called common sense is largely a matter

of good diet and digestion.”

“Oh, Doctor, you materialistic creature!” said Eva,

“to think of talking of a clergyman as if he were a

horse—to be managed by changing his feed!”

“Certainly, a man must be a good animal before he

can be a good man.”

“Well,” said Alice, “all I know is, that Mr. St. John

is perfectly, disinterestedly, heart and soul and body, devoted

to doing good among men; and if that is not noble

and grand and godlike, I don't know what is.”

“Well,” said Dr. Campbell, “I have a profound respect

for all those fellows that are trying to mop out the

Atlantic Ocean; and he mops cheerfully and with good

courage.”

“It's perfectly hateful of you, Doctor, to talk so,”

said Eva.

“Well, you know I don't go in for interfering with

nature—having noble, splendid fellows waste and wear

themselves down, to keep miserable scalawags and ill-begotten

vermin from dying out as they ought to. Nature

is doing her best to kill off the poor specimens of

the race, begotten of vice and drunkenness; and what

you call Christian charity is only interference.”

“But you do it, Doctor; you know you do. Nobody

does more of that very sort of thing than you do, now.

Don't you visit, and give medicine and nursing, and all

that, to just such people?”

“I may be a fool for doing it, for all that,” said the

Doctor. “I don't pretend to stick to my principles any

better than most people do. We are all fools, more or

less; but I don't believe in Christian charity: it's all

wrong—this doctrine that the brave, strong good specimens

of the race are to torment and tire and worry their

lives out to save the scum and dregs. Here's a man

who, by economy, honesty, justice, temperance and hard

work, has grown rich, and has houses, and lands, and

gardens, and pictures, and what not, and is having a

good time as he ought to have, and right by him is another

who, by dishonesty, and idleness, and drinking,

has come to rags and poverty and sickness. Shall the

temperate and just man deny himself enjoyment, and

spend his time, and risk his health, and pour out his

money, to take care of the wife and children of this

scalawag? There's the question in a nutshell? and I

say, no! If scalawags find that their duties will be

performed for them when they neglect them, that's all

they want. What should St. John live like a hermit for?

deny himself food, rest and sleep? spend a fortune that

might make him and some nice wife happy and comfortable,

on drunkards' wives and children? No sense in it.”

“That's just where Christianity stands above and

opposite to nature,” said Bolton, from his corner. “Nature

says, destroy. She is blindly striving to destroy

the maimed and imperfect. Christianity says, save. Its

God is the Good Shepherd, who cares more for the

one lost sheep than for the ninety and nine that went

not astray.”

“Yes,” said Eva; “He who was worth more than

all of us put together, came down from heaven to labor

and suffer and die for sinners.”

“That's supernaturalism,” said Dr. Campbell. “I

don't know about that.”

“That's what we learn at church,” said Eva, “and

what we believe; and it's a pity you don't, Doctor.”

“Oh, well,” said Dr. Campbell, lighting his cigar,

previous to going out, “I won't quarrel with you. You

might believe worse things. St. John is a good fellow,

and, if he wants a doctor any time, I told him to call me.

Good night.”

“Did you ever see such a creature?” said Eva.

“He talks wild, but acts right,” said Alice.

“You had him there about visiting poor folks,” said

Jim. “Why, Campbell is a perfect fool about people

in distress—would give a fellow watch and chain, and

boots and shoes, and then scold anybody else that wanted

to go and do likewise.”

“Well, I say such discussions are fatiguing,” said

Alice. “I don't like people to talk all round the points

of the compass so.”

“Well, to change the subject, I vote our evening a

success,” said Jim. “Didn't we all behave beautifully!”

“We certainly did,” said Eva.

“Isn't Miss Dorcas a beauty!” said Jim.

“Come, now, Jim; no slants,” said Alice.

“I didn't mean any. Honest now, I like the old girl.

She's sensible. She gets such clothes as she thinks right

and proper, and marches straight ahead in them, instead

of draggling and draggletailing after fashion; and it's a

pity there weren't more like her.”

“Dress is a vile, tyrannical Moloch,” said Eva. “We

are all too much enslaved to it.”

“I know we are,” said Alice. “I think it's the question

of our day, what sensible women of small means are

to do about dress; it takes so much time, so much

strength, so much money. Now, if these organizing,

convention-holding women would only organize a dress

reform, they would do something worth while.”

“The thing is,” said Eva, “that in spite of yourself

you have to conform to fashion somewhat.”

“Unless you do as your Quaker friends do,” said

Bolton.

“By George,” said Jim Fellows, “those two were the

best dressed women in the room. That little Ruth was

seductive.”

“Take care; we shall be jealous,” said Eva.

“Well,” said Bolton, rising, “I must walk up to the

printing-office and carry that corrected proof to Daniels.”

“I'll walk part of the way with you,” said Harry.

“I want a bit of fresh air before I sleep.”

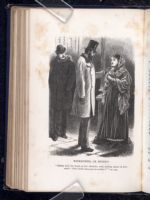

[ILLUSTRATION]

WICKEDNESS, OR MISERY?

"Bolton laid his hand on her shoulder, and, looking down on her,

said: 'Poor child, have you no mother?'"—p. 197.

[Description: 710EAF. Illustration page. Image of two well dressed men, one of whom is talking to a young woman wrapped in a ragged shawl. He has his hand on her shoulder.]