| Artemus Ward's panorama | ||

THE LECTURE.

By Armetus Ward.

YOU are entirely welcome ladies and gentlemen

to my little picture-shop.[1]

I couldn't give you a very clear idea of the

Mormons—and Utah—and the Plains—and the

Rocky Mountains—without opening a picture-op—and

therefore I open one.

I don't expect to do great things here—but I

have thought that if I could make money enough

to buy me a passage to New Zealand[2]

I should feel

that I had not lived in vain.

I don't want to live in vain.—I'd

rather live in Margate—or here. But

had given it a little more ventilation.[3]

If you should be dissatisfied with anything here

to-night—I will admit you all free in New Zealand—if

you will come to me there for the orders. Any

respectable cannibal will tell you where

I live. This shows that I have a forgiving

spirit.

I really don't care for money. I only travel

round to see the world and to exhibit my clothes.

These clothes I have on were a great

success in America.[4]

How often do large fortunes ruin young men!

I should like to be ruined, but I can get

on very well as I am.

I am not an Artist. I don't paint myself—

though perhaps if I were a middle-aged single lady

I should—yet I have a passion for pictures.—I

have had a great many pictures—photographs—

taken of myself. Some of them are very pretty

—rather sweet to look at for a short

time—and as I said before I like them. I've

always loved pictures.

I could draw on wood at a very tender age.

When a mere child I once drew a small cartload

of raw turnips over a wooden bridge.

—The people of the village noticed me. I

drew their attention. They said I had a

future before me. Up to that time I had an idea

it was behind me.

Time passed on. It always does by the way.

You may possibly have noticed that Time

passes on.—It is a kind of way Time has.

I became a man. I haven't distinguished

myself at all as an artist—but I have always been

more or less mixed up with Art. I have an uncle

who takes photographs—and I have a servant

who—takes anything he can get his hands on.

When I was in Rome—Rome in New York

State I mean—a distinguished sculpist wanted

to sculp me. But I said “No.” I saw through

—he would have flooded the market with my

busts—and I couldn't stand it to see everybody

going round with a bust of me. Everybody

would want one of course—and wherever I should

go I should meet the educated classes with my

bust, taking it home to their families. This

would be more than my modesty could

stand—and I should have to return to

America—where my creditors are.

I like Art. I admire dramatic Art—although

I failed as an actor.

It was in my schoolboy days that I failed as

an actor.[5]

—The play was the “Ruins of Pom

very successful performance—but it was better

than the “Burning Mountain.” He was not

good. He was a bad Vesuvius.

The remembrance often makes me ask—

“Where are the boys of my youth?”—I assure

you this is not a conundrum.—Some are

amongst you here—some in America—

some are in gaol.—

Hence arises a most touching question—

“Where are the girls of my youth?” Some are

married—some would like to be.

Oh my Maria! Alas! she married another.

They frequently do. I hope she is happy—because

I am.[6]

—Some people are not happy. I have

noticed that.

A gentleman friend of mine came to me one

day with tears in his eyes. I said “Why these

weeps?” He said he had a mortgage on his

farm—and wanted to borrow £200. I lent him

the money—and he went away. Some time after

he returned with more tears. He said he must

leave me for ever. I ventured to remind him of

the £200 he borrowed. He was much cut up. I

thought I would not be hard upon him—so told

him I would throw off one hundred pounds. He

brightened—shook my hand—and said—“Old

friend—I won't allow you to outdo me in liberality—I'll

throw off the other hundred.”

As a manager I was always rather more successful

than as an actor.

Some years ago I engaged a celebrated Living

American Skeleton for a tour through Australia.

splendid skeleton. He didn't weigh anything

scarcely—and I said to myself—the people of

Australia will flock to see this tremendous curiosity.

It is a long voyage—as you know—from

New York to Melbourne—and to my utter surprise

the skeleton had no sooner got out to sea

than he commenced eating in the most horrible

manner. He had never been on the ocean before

—and he said it agreed with him.—I thought

so!—I never saw a man eat so much in my

life. Beef—mutton—pork—he swallowed them

all like a shark—and between meals he was

often discovered behind barrels eating hard-boiled

eggs. The result was that when we reached

Melbourne this infamous skeleton weighed 64

pounds more than I did!

I thought I was ruined—but I wasn't. I

took him on to California—another very long

I exhibited him as a Fat Man.[7]

This story hasn't anything to do with my

Entertainment, I know—but one of the

principal features of my Entertainment is that

it contains so many things that don't have anything to

do with it.

My Orchestra is small—but I am sure it is

very good—so far as it goes. I give my

pianist ten pounds a night—and his

washing.[8]

I like Music.—I can't sing. As a singist I

am not a success. I am saddest when I

sing. So are those who hear me. They are sadder

even than I am.

The other night some silver-voiced young

men came under my window and sang—“Come

where my love lies dreaming.”—I didn't go.

I didn't think it would be correct.

I found music very soothing when I lay ill

with fever in Utah—and I was very ill—I was

fearfully wasted.—My face was hewn down to

nothing—and my nose was so sharp I didn't dare

stick it into other people's business—for fear it

would stay there—and I should never get it

again. And on those dismal days a Mormon lady

—she was married—tho' not so much so as

her husband—he had fifteen other wives—she used

to sing a ballad commencing “Sweet bird—do

not fly away!”—and I told her I wouldn't.—

praised her.

I met a man in Oregon who hadn't any teeth

—not a tooth in his head—yet that man

could play on the bass drum better than

any man I ever met.—He kept a hotel.

They have queer hotels in Oregon. I remember

one where they gave me a bag of oats for a

pillow—I had night mares of course. In

the morning the landlord said—How do you feel

—old hoss—hay?—I told him I felt my oats.

[9]

PERMIT me now to quietly state that altho' I

am here with my cap and bells I am also here

with some serious descriptions of the Mormons

—their manners—their customs—and while the

pictures I shall present to your notice are by no

means works of art—they are painted from pho

am sure I need not inform any person present

who was ever in the territory of Utah that they

are as faithful as they could possibly be.[11]

I went to Great Salt Lake City by way of

california.[12]

I went to California on the steamer “Ariel.”

—This is the steamer “Ariel.”

Oblige me by calmly gazing on the steamer

“Ariel”—and when you go to California

be sure and go on some other steamer—

because the “Ariel” isn't a very good one.

When I reached the “Ariel”—at pier No. 4

—New York—I found the passengers in a state

of great confusion about their things—which

were being thrown around by the ship's porters

in a manner at once damaging and idiotic.—So

great was the excitement—my fragile form was

smashed this way—and jammed that way—till

occupied by two middle-aged females—who said

“Base man—leave us—O, leave us!”—I left them

—Oh—I left them!

We reach Accapulco on the coast of Mexico

in due time. Nothing of special interest occurred

at Accapulco—only some of the Mexican ladies

are very beautiful. They all have brilliant black

hair—hair “black as starless night”—if I

may quote from the “Family Herald.” It

don't curl.—A Mexican lady's hair never curls

—it is straight as an Indian's. Some

people's hair won't curl under any circumstances.

—My hair won't curl under two shillings.[13]

The great thoroughfare of the imperial city

of the Pacific Coast

The Chinese form a large element in the population

of San Francisco—and I went to the

Chinese Theatre.

A Chinese play often lasts two months.

Commencing at the hero's birth, it is cheerfully

conducted from week to week till he is either

killed or married.

The night I was there a Chinese comic vocalist

sang a Chinese comic song. It took him six

weeks to finish it—but as my time was limited I

went away at the expiration of 215 verses.

There were 11,000 verses to this song—the

chorus being “Tural lural dural, ri fol day”—

which was repeated twice at the end of each verse

—making—as you will at once see—the appalling

number of 22,000 “tural lural dural, ri fol

days”—and the man still lives.

Virginia City—in the bright new State of

Nevada.[14]

A wonderfu little city—right in the heart

of the famous Washoe silver regions—the

mines of which annually produce over twenty-five

millions of solid silver. This silver is melted

into solid bricks—of about the size of ordinary

with mules. The roads often swarm with these

silver wagons.

One hundred and seventy-five miles to the

east of this place are the Reese River Silver

Mines—which are supposed to be the richest in

the world.

The great American Desert in winter-time—

the desert which is so frightfully gloomy always.

No trees—no houses—no people—save the

miserable beings who live in wretched huts and

have charge of the horses and mules of the

Overland Mail Company.

This picture is a great work of art.—It is

an oil painting—done in petroleum. It

is by the Old Masters. It was the last thing they

did before dying. They did this and

then they expired.

The most celebrated artists of London are so

delighted with this picture that they come to the

Hall every day to gaze at it. I wish you were

nearer to it—so you could see it better. I wish

I could take it to your residences and let you see

London come here every morning before daylight

with lanterns to look at. They say they never

saw anything like it before—and they hope

they never shall again.

When I first showed this picture in New

York, the audience were so enthusiastic in their

admiration of this picture that they called

for the Artist—and when he appeared they threw

brickbats at him.[15]

A bird's-eye-view of Great Salt Lake City

—the strange city in the Desert about which

so much has been heard—the city of the people

who call themselves Saints.[16]

I know there is much interest taken in these

remarkable people—ladies and gentlemen—and

PART OF SALT LAKE CITY,

Viewed From A Distance

The City is laid out in squares; each house standing on an acre

and a quarter of ground, with a canal of clear water flowing in front.

(This picture joins on the one which follows it.)

SALT LAKE CITY.

From The Heights Behind It.

The building in the foreground is the Mormon arsenal. To the

right, in the mid-distance, is the River Jordan, flowing from Lake

Utah to the Salt Lake. The valley through which the Jordan flows is

one of the most fertile on the North American continent.

part of my Entertainment entirely

serious.—I will not—then—for the next ten

minutes—confine myself to my subject.

Some seventeen years ago a small band of

Mormons—headed by Brigham Young—commenced

in the present thrifty metropolis of Utah.

The population of the territory of Utah is over

100,000—chiefly Mormons—and they are increasing

at the rate of from five to ten thousand

almost exclusively confined to English and

Germans.—Wales and Cornwall have contributed

largely to the population of Utah during

the last few years. The population of Great Salt

Lake City is 20,000.—The streets are eight

A stream of pure mountain spring water courses

through each street—and is conducted into the

Gardens of the Mormons. The houses are mostly

of adobe—or sun-dried brick—and present a neat

and comfortable appearance.—They are usually

a story and a half high. Now and then you see

a fine modern house in Salt Lake City—but

no house that is dirty, shabby, and dilapidated—

because there are no absolutely poor people in

Utah. Every Mormon has a nice garden—and

every Mormon has a tidy dooryard.—Neatness

is a great characteristic of the Mormons.

The Mormons profess to believe that they are

the chosen people of God—they call themselves

Latter-day Saints—and they call us

people of the outer world Gentiles. They say

successor of Joseph Smith—who founded

the Mormon religion. They also say they are

authorised—by special revelation from Heaven—

to marry as many wives as they can comfortably

support.

This wife-system they call plurality—the

world calls it polygamy. That at its best it is an

accursed thing—I need not of course inform you

—but you will bear in mind that I am here

as a rather cheerful reporter of what I saw in

Utah—and I fancy it isn't at all necessary for

me to grow virtuously indignant over something

we all know is hideously wrong.

You will be surprised to hear—I was amazed

to see—that among the Mormon women there are

some few persons of education—of positive cultivation.

educated people—but they are by no means

the community of ignoramuses so many writers

have told us they were.

The valley in which they live is splendidly

favoured. They raise immense crops. They have

mills of all kinds. They have coal—lead—and

silver mines. All they eat—all they drink—all

they wear they can produce themselves—and still

have a great abundance to sell to the gold regions

of Idaho on the one hand—and the silver regions

of Nevada on the other.

The President of this remarkable community

—the head of the Mormon Church—is

Brigham Young.—He is called President

Young—and Brother Brigham. He is about 54

years old—altho' he doesn't look to be over 45.

He has sandy hair and whiskers—is of medium

height—and is a little inclined to corpulency.

is more absolute than that of any living sovereign

—yet he uses it with such consummate discretion

that his people are almost madly devoted

to him—and that they would cheerfully die for

him if they thought the sacrifice were demanded

—I cannot doubt.

He is a man of enormous wealth.—Onetenth

of everything sold in the territory of Utah

goes to the Church—and Mr. Brigham Young

is the Church. It is supposed that he speculates

with these funds—at all events—he is one of

the wealthiest men now living—worth several

millions—without doubt.—He is a bold—bad

man—but that he is also a man of extraordinary

administrative ability no one can doubt who

has watched his astounding career for the past

ten years. It is only fair for me to add that he

treated me with marked kindness during my

sojourn in Utah.

The West Side of Main Street—Salt Lake City

—including a view of the Salt Lake Hotel.—It

is a temperance hotel.[18]

I prefer temperance

hotels—altho' they sell worse liquor than

Hotel sells none—nor is there a bar in all

Salt Lake City—but I found when I was thirsty

—and I generally am—that I could get some

very good brandy of one of the Elders—on the

sly—and I never on any account allow my business to

interfere with my drinking.

There is the Overland Mail Coach.[19]

—That

is, the den on wheels in which we have been

—Those of you who have been in Newgate[20] —

— — — — — — —

— — — — — — —

and staid there any length of time—as

visitors—can realize how I felt.

The American Overland Mail Route commences

at Sacramento—California—and ends

at Atchison—Kansas. The distance is two

thousand two hundred miles—but you go part

completed from Sacramento—California—to

Fulsom—California—which only leaves two

thousand two hundred and eleven miles to go by

coach. This breaks the monotony—it

came very near breaking my back.

The Mormon Theatre.—This edifice is the

exclusive property of Brigham Young. It will

comfortably hold 3,000 persons—and I beg you

will believe me when I inform you that its interior

is quite as brilliant as that of any theatre in

London.[22]

The actors are all Mormon amateurs, who

charge nothing for their services.

You must know that very little money is taken

at the doors of this theatre. The Mormons

mostly pay in grain—and all sorts of articles.

The night I gave my little lecture there—

among my receipts were corn—flour—pork—

shell.

One family went in on a live pig—and a man

attempted to pass a “yaller dog” at the Box

Office—but my agent repulsed him. One offered

me a doll for admission—another infants'

clothing.—I refused to take that.—As a

general rule I do refuse.

In the middle of the parquet—in a rocking

chair—with his hat on—sits Brigham Young.

When the play drags—he either goes out or falls

into a tranquil sleep.

A portion of the dress-circle is set apart for

the wives of Brigham Young. From ten to

twenty of them are usually present. His

children fill the entire gallery—and more

too.

The East Side of Main Street—Salt Lake

City—with a view of the Council Building.—

The legislature of Utah meets there. It is like

all legislative bodies. They meet this winter to

repeal the laws which they met and made last

winter—and they will meet next winter to repeal

the laws which they met and made this winter

I dislike to speak about it—but it was

in Utah that I made the great speech of my life.

I wish you could have heard it. I have a fine

education. You may have noticed it. I

speak six different languages—London—

Chatham—and Dover—Margate—Brighton—

MAIN STREET, SALT LAKE CITY.

The building to the extreme right is the House of Legislature,

where

the representatives of the territory of Utah hold their meetings.

The

second house on the right is the Post Office. Main Street is 132

feet in

breadth.

me to college when I was quite young. During

the vacation I used to teach a school of whales—

and there's where I learned to spout.—I don't

expect applause for a little thing like that. I wish

you could have heard that speech—however. If

Cicero—he's dead now—he has gone from us

—but if Old Ciss[23] could have heard that

effort it would have given him the rinderpest.

I'll tell you how it was. There are stationed in

Utah two regiments of U.S. troops—the 21st

from California—and the 37th from Nevada. The

20-onesters asked me to present a stand of colours

abounding in eloquence of a bold and brilliant

character—and also some sweet talk—real

pretty shop-keeping talk—that I worked the

enthusiasm of those soldiers up to such a

pitch—that they came very near shooting me on the spot.[24]

Brigham Young's Harem.—These are the

houses of Brigham Young. The first on the

right is the Lion House—so called because a

crouching stone lion adorns the central front

window. The adjoining small building is Brigham

Young's office—and where he receives his visitors.

—The large house in the centre of the picture

—which displays a huge bee-hive—is called the

Bee House—the bee-hive is supposed to be

symbolical of the industry of the Mormons.—

Mrs. Brigham Young the first—now quite an old

lady—lives here with her children. None of the

other wives of the prophet live here. In the rear

children are educated.

Brigham Young has two hundred wives.

Just think of that! Oblige me by thinking of that.

That is—he has eighty actual wives, and he is

spiritually married to one hundred and twenty

more. These spiritual marriages—as the

Mormons call them—are contracted with

aged widows—who think it a great honour to be

sealed—the Mormons call it being sealed—

to the Prophet.

So we may say he has two hundred wives.

He loves not wisely—but two hundred

well. He is dreadfully married. He's the

most married man I ever saw in my life.

I saw his mother-in-law while I was there. I

can't exactly tell you how many there is

of her—but it's a good deal. It strikes me that

family—unless you're very fond of excitement.

A few days before my arrival in Utah—

Brigham was married again—to a young and

really pretty girl[25]

—but he says he shall stop

now. He told me confidentially that he shouldn't

get married any more. He says that all he wants

now is to live in peace for the remainder of his days

—and have his dying pillow soothed by the loving

hands of his family. Well—that's all right—

that's all right—I suppose—but if all his

family soothe his dying pillow—he'll

have to go out-doors to die.

By the way—Shakespeare endorses polygamy.

—He speaks of the Merry Wives of Windsor.

How many wives did Mr. Windsor have

—But we will let this pass.

Some of these Mormons have terrific families.

I lectured one night by invitation in the Mormon

village of Provost—but during the day I rashly

gave a leading Mormon an order admitting himself

and family.—It was before I knew that

he was much married—and they filled the

room to overflowing. It was a great success

—but I didn't get any money.

Heber C. Kimball's Harem.—Mr. C.

Kimball is the first vice-president of the Mormon

church—and would—consequently—succeed to

the full presidency on Brigham Young's death.

Brother Kimball is a gay and festive cuss of

some seventy summers—or some'ers there

MR. HEBER C. KIMBALL'S HAREM.

The seraglio of Mr. Kimball is large. Unlike Brigham Young,

he does not keep his wives under one roof, but has many buildings in

his garden, where he assorts them according to their temper and their

adaptability to dwelling together in peace.

cattle and a hundred head of wives.[26]

He says they are awful eaters.

Mr. Kimball had a son—a lovely young

man—who was married to ten interesting

wives. But one day—while he was absent

from home—these ten wives went out

walking with a handsome young man—

which so enraged Mr. Kimball's son—which

made Mr. Kimball's son so jealous—that he

shot himself with a horse pistuel.

The doctor who attended him—a very

scientific man—informed me that the bullet

entered the inner parallelogram of his diaphragmatic

thorax, superinducing membranous

hemorrhage in the outer cuticle of his basiliconthamaturgist.

It killed him. I should have

thought it would.

(Soft music)[27]

I hope his sad end will be a warning to all

young wives who go out walking with handsome

young men. Mr. Kimball's son is now

—the myrtle—and the willow. This

music is a dirge by the eminent pianist for Mr.

Kimball's son. He died by request.

I regret to say that efforts were made to make

a Mormon of me while I was in Utah.

It was leap-year when I was there—and

seventeen young widows—the wives of a deceased

Mormon—offered me their hearts and

hands. I called on them one day—and taking

their soft white hands in mine—which made

eighteen hands altogether—I found them

in tears.

And I said—“Why is this thus? What is

the reason of this thusness?”

They hove a sigh—seventeen sighs of different

size.—They said—

“Oh—soon thou wilt be gonested away!”

I told them that when I got ready to leave a

place I wentested.

They said—“Doth not like us?”

I said—“I doth—I doth!”

I also said—“I hope your intentions are

honourable—as I am a lone child—my parents

being far—far away.

They then said—“Wilt not marry us?”

I said—“Oh—no—it cannot was.”

Again they asked me to marry them—and

again I declined. When they cried—

“Oh—cruel man! This is too much—oh!

too much!”

I told them that it was on account of

the muchness that I declined.[28]

This is the Mormon Temple.

It is built of adobe—and will hold five thousand

persons quite comfortably. A full brass and

—and the choir—I may add—is a remarkably

good one.

Brigham Young seldom preaches now. The

younger elders—unless on some special occasion—conduct

the services. I only heard Mr.

Young once. He is not an educated man—but

speaks with considerable force and clearness.

The day I was there there was nothing coarse in

his remarks.

The foundations of the Temple.

These are the foundations of the magnificent

Temple the Mormons are building. It is to be

FOUNDATIONS OF THE NEW TEMPLE.

From this picture and that which succeeds may be formed some idea

of how far the building of the New Temple had progressed at the time

of the lecturer's visit. The stones were being shaped into form by

masons who contributed their labour gratuitously.

FOUNDATIONS OF THE NEW TEMPLE.

Continued.

The block is forty rods squre, and contains ten acres. The

position

is 4,300 feet above the level of the sea in latitude 40°

45' 44" N., and

longitude 112° 6' 8" W. of Greenwich.

of ground. They say it shall eclipse in splendour

all other temples in the world. They also say it

shall be paved with solid gold.[29]

It is perhaps worthy of remark that the architect

of this contemplated gorgeous affair repudiated

Mormonism—and is now living in London.

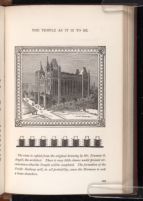

The Temple as it is to be.

This pretty little picture is from the architect's

design—and cannot therefore—I suppose—be

called a fancy sketch.[30]

Should the Mormons continue unmolested—I

think they will complete this rather remarkable

edifice.

Great Salt Lake.—The great salt dead sea

of the desert.

I know of no greater curiosity than this inland

sea of thick brine. It is eighty miles wide—and

one hundred and thirty miles long. Solid masses

of salt are daily washed ashore in immense heaps

—and the Mormon in want of salt has only to go

to the shore of this lake and fill his cart. Only—

the salt for table use has to be subjected to a

boiling process.[31]

These are facts—susceptible of the clearest

possible proof. They tell one story about this

lake—however—that I have my doubts about.

They say a Mormon farmer drove forty head of

cattle in there once—and they came out

first-rate pickled beef.—

I sincerely hope you will excuse my absence

—I am a man short—and have to work the

moon myself.[32]

I shall be most happy to pay

a good salary to any respectable

boy of good parentage and education

who is a good moonist.

The Endowment House.[33]

In this building the Mormon is initiated into

the mysteries of the faith.

Strange stories are told of the proceedings

which are held in this building—but I have no

possible means of knowing how true they may be.

THE ENDOWMENT HOUSE.

That which takes place within this building travellers may guess

at but are not permitted to know. It is where the Mormon marriages

are celebrated. On the mountain above a figure out of all proportion

to the scenery is supposed to represent Artemus Ward attacked by a

bear in front and a pack of wolves in the rear.

ENTRANCE TO ECHO CANYON.

High bluffs of yellow colour and conglomerate formation, full of

small fossils. The buildings at the base constitute Weber's Station,

where the coach stops for the mules to be changed, and the passengers

to obtain refreshments.

Slat Lake City is fifty-five miles behind us—

and this is Echo Canyon—in reaching which we

are supposed to have crossed the summit of the

Wahsatch Mountains. These ochre-coloured

bluffs—formed of conglomerate sandstone—

and full of fossils—signal the entrance to the

Canyon. At its base lies Weber Station.

Echo Canyon is about twenty-five miles long.

It is really the sublimest thing between the Missouri

and the Sierra Nevada. The red wall to

the left develops further up the Canyon into

pyramids—buttresses—and castles—honey

combed and fretted in nature's own massive

magnificence of architecture.

In 1856—Echo Canyon was the place selected

by Brigham Young for the Mormon General

Wells to fortify and make impregnable against

the advance of the American army—led by

General Albert Sidney Johnson. It was to have

been the Thermopylæ of Mormondom—but it

wasn't. General Wells was to have done

Leonidas—but he didn't.

A more cheerful view of the Desert.

The wild snow storms have left us—and we

have thrown our wolf-skin overcoats aside. Certain

tribes of far-western Indians bury their distinguished

dead by placing them high in air and

covering them with valuable furs—that is a very

fair representation of these mid-air tombs. Those

THE INDIANS ON THE PLAINS.

On the right of the picture is the scaffold erected for an Indian

grave. The corpse is placed at the top of it, out of the way of the

wolves, though not so protected but what the vultures and other birds of

carrion soon render it a mere skeleton.

my artist says so. I had the picture two years

before I discovered the fact.—The artist came

to me about six months ago—and said—“It is

useless to disguise it from you any longer—

they are horses.”[34]

It was while crossing this desert that I was

surrounded by a band of Ute Indians. They

were splendidly mounted—they were dressed

in beaver-skins—and they were armed with

rifles—knives—and pistols.

What could I do?—What could a poor old

orphan do? I'm a brave man.—The day

before the Battle of Bull's Run I stood in the

highway while the bullets—those dreadful

messengers of death—were passing all

around me thickly—IN WAGGONS—on

were too many of these Injuns—there were

forty of them—and only one of me—and so I

said—

“Great Chief—I surrender.” His name was

Wocky-bocky.

He dismounted—and approached me. I saw

his tomahawk glisten in the morning sunlight.

Fire was in his eye. Wocky-bocky came very

close to me and seized me by the hair of my head.

He mingled his swarthy fingers with my golden

OUR ENCOUNTER WITH THE INDIANS.

Utah Territory contains Indians of two races—the Shoshones and

the Utes. The Utes are very friendly with the Mormons, who treat

them with uniform kindness. It is commonly believed that a secret

treaty of alliance exists between Brigham Young and the chiefs of the

Indian tribes. (The left hand portion of the illustration belongs to

the preceding picture.)

across my lily-white face. He said—

“Torsha arrah darrah mishky bookshean!”

I told him he was right.

Wocky-bocky again rubbed his tomahawk

across my face, and said—“Wink-ho—loo-boo!”

Says I—“Mr. Wocky-bocky”—says I—

“Wocky—I have thought so for years—and

so's all our family.”

He told me I must go the tent of the Strong-Heart—and

eat raw dog.[36]

It don't agree with

me. I prefer simple food. I prefer pork-pie

—because then I know what I'm eating.

me—I had to eat it or starve. So at the expiration

of two days I seized a tin plate and went

to the chief's daughter—and I said to her in a

silvery voice—in a kind of German-silvery

voice—I said—

“Sweet child of the forest, the pale-face wants

his dog.”

There was nothing but his paws! I had

paused too long! Which reminds me that

time passes. A way which time has.

I was told in my youth to seize opportunity.

I once tried to seize one. He was rich. He had

diamonds on. As I seized him—he knocked me

down. Since then I have learned that he who

seizes opportunity sees the penitentiary.

The Rocky Mountains.

I take it for granted you have heard of these

popular mountains. In America they are

regarded as a great success, and we all love

dearly to talk about them. It is a kind of weakness

with us. I never knew but one American

who hadn't something—sometime—to say about

the Rocky Mountains—and he was a deaf and

dumb man, who couldn't say anything about

nothing.

But these mountains—whose summits are

snow-covered and icy all the year round—are too

grand to make fun of. I crossed them in the

winter of '64—in a rough sleigh drawn by four

mules.

This sparkling waterfall is the Laughing-Water

alluded to by Mr. Longfellow in his Indian

poem—“Higher-Water.” The water is

higher up there.

The plains of Colorado.

These are the dreary plains over which we

rode for so many weary days. An affecting incident

occurred on these plains some time since,

which I am sure you will pardon me for introducing

here.

On a beautiful June morning—some sixteen

years ago—

(Music, very loud till the scene is off.)

—and she fainted on Reginald's breast![37]

The Prairie on Fire.

A prairie on fire is one of the wildest and

grandest sights that can possibly be imagined.

These fires occur—of course—in the summer

—when the grass is dry as tinder—and the

flames rush and roar over the prairie in a manner

frightful to behold. They usually burn better

than mine is burning to-night. I try to make

my prairie burn regularly—and not disappoint

the public—but it is not as high-principled as I am.[38]

THE PRAIRIE ON FIRE.

Artemus Ward had an opportunity of seeing part of a Prairie on

Fire, just as he entered the State of Kansas. The grandeur of the

scene made a very deep impression upon him. He frequently alluded

to it in conversation.

THE PRAIRIE ON FIRE.

Continued.

The effect of the Prairie being on Fire was illustrated in the

panorama by means of a revolving cloth behind; a portion of the

picture being transparent.

BRIGHAM YOUNG AT HOME.

This is, of course, a mere fancy sketch. It was roughly designed

by Artemus Ward himself. According to his own statement, made

in a very playful manner, it represents that which he saw on an

afternoon passed with the prophet at the palace.

The last picture I have to show you represents

Mr. Brigham Young in the bosom of his family.

His family is large—and the olive branches

around his table are in a very tangled condition.

He is more a father than any man I know.

When at home—as you here see him—he

ought to be very happy with sixty wives

sixty children to soothe his distracted

mind. Ah! my friends—what is home without

a family

What will become of Mormonism? We all

know and admit it to be a hideous wrong—a

great immoral stain upon the 'scutcheon of the

United States. My belief is that its existence is

dependent upon the life of Brigham Young.

His administrative ability holds the system together—his

power of will maintains it as the

faith of a community. When he dies—Mormonism

will die too. The men who are around

him have neither his talent nor his energy. By

means of his strength it is held together. When

he falls—Mormonism will also fall to pieces.

[39]

That lion—you perceive—has a tail. It is a

long one already. Like mine—it is to be continued

in our next.[40]

“My little picture-shop.”—I have already stated that the

room used was the lesser of the two on the first-floor of the

Egyptian Hall. The panorama was to the left on entering,

and Artemus Ward stood at the south-east corner facing the

door. He had beside him a music-stand, on which for the

first few days he availed himself of the assistance afforded by

a sheet of foolscap on which all his “cues” were written out

in a large hand. The proscenium was covered with dark

cloth, and the picture bounded by a great gilt frame. On the

rostrum behind the lecturer was a little door giving admission

to the space behind the picture where the piano was placed.

Through this door Artemus would disappear occasionally in

the course of the evening, either to instruct his pianist to play

a few more bars of music, to tell his assistants to roll the

picture more quickly or more slowly, or to give some instructions

to the man who worked “the moon.” The little

lecture-room was thronged nightly during the very few

weeks of its being open.

“To New Zealand.”—Artemus Ward seriously contemplated

a visit to Australia, after having made the tour of

England. He was very much interested in all Australian

affairs, had a strong desire to see the lands of the South, and

looked forward to the long sea-voyage as one of the means by

which he should regain his lost health.

“More ventilation.”—The heat and closeness of the

densely-packed room was a cause of common complaint

among the audience.

“These clothes, etc.”—This was one of poor Artemus's jokes

which owed more of its success to its oddity than to its

veracity. While lecturing at the Egyptian Hall he wore a

fashionably-cut dress coat in the evening. It was what he

had never done during his lecture-career in the States, and

he used privately to complain how uncomfortable he felt in it.

He assumed the most deplorable look when pointing out his

costume to his audience. His voice dropped into a moody

reflective tone, and then suddenly passed into a much higher

key when he commenced to allude to “large fortunes.” He

seemed to have shaken off the embarrassment of his fashionable

clothes, and to be glad to pass on to another subject. In the

punctuation of the succeeding paragraph of the lecture, I have

endeavoured to convey an idea of the long pause he made

between some of his sentences.

“Failed as an actor.”—Artemus made many attempts as an

amateur actor, but never to his own satisfaction. He was very

fond of the society of actors and actresses. Their weaknesses

amused him as much as their talents excited his admiration.

One of his favourite sayings was that the world was made up

of “men, women, and the people on the stage.”

“Because I am!”—Spoken with a sigh. It was a joke

which always told. Artemus never failed to use it in his

“Babes in the Wood” lecture, and the “Sixty Minutes in

Africa,” as well as in the Mormon story.

“As a Fat Man.”—The reader need scarcely be informed

that this narrative is about as real as “A. Ward's Snaiks,” and

about as much matter-of-fact as his journey through the States

with a wax-work show.

“My Pianist, &c.” That a good pianist could be hired

for a small sum in England was a matter of amusement to

Artemus. More especially when he found a gentleman who

was obliging enough to play anything he desired, such as

break-downs and airs which had the most absurd relation to

the scene they were used to illustrate. In the United States

his pianist was desirous of playing music of a superior order,

much against the consent of the lecturer.

“Permit me now.” Though the serious part of the lecture

was here entered upon, it was not delivered in a graver tone

than that in which he had spoken the farcicalities of the

prologue. Most of the prefatory matter was given with an

air of earnest thought; the arms sometimes folded, and the chin

resting on one hand. On the occasion of his first exhibiting

the panorama at New York he used a fishing-rod to point out

the picture with; subsequently he availed himself of an old

umbrella. In the Egyptian Hall he used his little riding-whip.

“Photographs.” They were photographed by Savage and

Ottinger, of Salt Lake City, the photographers to Brigham

Young.

Curtain. The picture was concealed from view during the

first part of the lecture by a crimson curtain. This was drawn

together or opened many times in the course of the lecture,

and at odd points of the picture. I am not aware that

Artemus himself could have explained why he caused the curtain

to be drawn at one place and not at another. Probably

he thought it to be one of his good jokes that it should shut

in the picture just when there was no reason for its being used.

“By way of California.” That is, he went by steamer

from New York to Aspinwall, thence across the Isthmus of

Panama by railway, and then from Panama to California by

another steamboat. A journey which then occupied about

three weeks.

“Under Two Shillings.” Artemus always wore his hair

straight until after his severe illness in Salt Lake City. So

much of it dropped off during his recovery that he became

dissatisfied with the long meagre appearance his countenance

presented when he surveyed it in the looking-glass. After his

lecture at the Salt Lake City Theatre he did not lecture again

until we had crossed the Rocky Mountains and arrived at

Denver City, the capital of Colorado. On the afternoon he

was to lecture there I met him coming out of an ironmonger's

store with a small parcel in his hand. “I want you, old

fellow,” he said, “I have been all round the City for them,

and I've got them at last.” “Got what?” I asked. “A pair

of curling-tongs. I am going to have my hair curled to lecture

in to-night. I mean to cross the plains in curls. Come home

with me and try to curl it for me. I don't want to go to any

idiot of a barber to be laughed at.” I played the part of

friseur. Subsequently he became his own “curlist,” as he

phrased it. From that day forth Artemus was a curly-haired

man.

“Virginia City.” The view of Virginia City given in

the panorama conveyed a very poor idea of the marvellous

capital of the silver region of Nevada. Artemus caused the

curtain to close up between his view of San Francisco and that

of Virginia City, as a simple means of conveying an idea of the

distance travelled between. To arrive at the city of silver we

had to travel from San Francisco to Sacramento by steamboat,

thence from Sacramento to Folsom by railroad, then by coach

to Placerville. At Placerville we commenced the ascent of the

Sierra Nevada, gaining the summit of Johnson's Pass about

four o'clock in the morning; thence we descended; skirted the

shores of Lake Tahoe, and arrived at Carson City, where

Artemus lectured. From Carson, the next trip was across an

arid plain, to the great silver region. Empire City, the first

place we struck, was composed of about fifty wooden houses

and three or four quartz mills. Leaving it behind us, we

passed through the Devil's Gate—a grand ravine, with precipitous

mountains on each side; then we came to Silver

City, Gold Hill, and Virginia. The road was all up-hill.

Virginia City itself is built on a ledge cut out of the side of

Mount Davidson, which rises some 9,000 feet above the sea

level—the city being about half way up its side. To Artemus

Ward the wild character of the scenery, the strange manners

of the red-shirted citizens, and the odd developments of life

met with in that uncouth mountain-town were all replete with

interest. We stayed there about a week. During the time of

our stay he explored every part of the place, met many old

friends from the Eastern States, and formed many new acquaintances,

with some of whom acquaintance ripened into

warm friendship. Among the latter was Mr. Samuel L.

Clemens, now well known as “Mark Twain.” He was then

sub-editing one of the three papers published daily in

Virginia—The Territorial Enterprise. Artemus detected in the

writings of Mark Twain the indications of great humorous

power, and strongly advised the writer to seek a better field

for his talents. Since then he has become a well-known New

York lecturer and author. With Mark Twain, Artemus made

a descent into the Gould and Curry Silver Mine at Virginia,

the largest mine of the kind, I believe, in the world. The

account of the descent formed a long and very amusing

article in the next morning's Enterprise. To wander about

the town and note its strange developments occupied Artemus

incessantly. I was sitting writing letters at the hotel when

he came in hurriedly, and requested me to go out with him.

“Come and see some joking much better than mine,” said

he. He led me to where one of Wells, Fargo, & Co.'s

express waggons was being rapidly filled with silver bricks.

Ingots of the precious metal, each almost as large as an ordinary

brick, were being thrown from one man to another to

load the waggon, just as bricks or cheeses are transferred from

hand to had by carters in England. “Good old jokes those,

Hingston. Good, solid `Babes in the Wood,' ” observed

Artemus. Yet that evening he lectured in “Maguire's Opera

House,” Virginia City, to an audience composed chiefly of

miners, and the receipts were not far short of eight hundred

dollars. A droll building it was to be called an “Opera

House,” and to bear that designation in a place so outlandish.

Perched up on the side of a mountain—from the windows of

the dressing rooms—a view could be had of fifty miles of the

American desert. It was an “Opera House;” yet in the

plain beneath it there were Indians who still led the life of

savages, and carried dried human scalps attached to their

girdles. It was an “Opera House;” yet, for many hundred

miles around it, Nature wore the roughest, sternest, and most

barren of aspects—no tree, no grass, no shrub, but the

colourless and dreary sage-brush. Every piece of timber,

every brick, and every stone in that “Opera House” had

been brought from California, over those snow-capped

Sierras, which, but a few years before had been regarded as

beyond the last outposts of civilisation. Every singer who

had sung, and every actor who had performed at that “Opera

House” had been whirled down the sides of the Nevada mountains,

clinging to the coach-top, and mentally vowing never

again to trust the safety of his neck on any such professional

excursion. The drama has been very plucky “out West.”

Thalia, Melpomene, and Euterpe become young ladies of

great animal spirits, and fearless daring, when they feel

the fresh breezes of the Pacific blowing in their faces. At

Virginia City we purchased black felt shirts half an inch thick.

and grey blankets of ample size to keep us warm for the

journey we were about to undertake. We invested also in

revolvers to defend ourselves against the Indians; a dozen

cold roast fowls to eat on the way; a demijohn of Bourbon

whisky, and a bagful of unground coffee. This last was

about as useful as any of our purchases. Thus provided, we

started across the desert on our way to Reese River, and

thence to Salt Lake City. Our coach was a fearfully lumbering

old vehicle of great strength, constructed for jolting over

rocky ledges, plunging into marshy swamps, and for rolling

through miles of sand. The horses were small and wiry,

accustomed to the country, and able to exist on anything

which it is possible for a horse to eat. There were four of us

in the coach. The “Pioneer Company's” man who drove

us was full of whisky and good-humour when he mounted

the box, and singing in chorus, “Jordan's a hard road to

travel on,” we bowled down the slope of Mount Davidson

towards the deserts of Nevada, en route for New Pass Station.

“Threw brickbats at him.” This portion of the panorama

was very badly painted. When the idea of having a panorama

was first entertained by Artemus he wished to have one

of great artistic merit. Finding considerable difficulty in

procuring one, and also discovering that the expense of a

real work of art would be beyond his means, he resolved on

having a very bad one, or one so bad in parts that its very

badness would give him scope for jest. In the small towns

of the Western States it passed very well for a first-class picture,

but what it was really worth in an artistic point of view

its owner was very well aware.

Salt Lake City.” Our stay in the Mormon capital extended

over six weeks. So cheerless was the place in midwinter,

that we should not have stayed half that time had not

Artemus Ward succumbed to an attack of typhoid fever

almost as soon as we arrived. The incessant travel by night

and day, the depressing effect produced by intense cold,

travelling through leagues of snow and fording half-frozen

rivers at midnight, the excitement of passing through Indian

country, and some slight nervous apprehension of how he

would be received among the Mormons, considering that he

had ridiculed them in a paper published some time before, all

conspired to produce the illness which resulted. Fever of

the typhoid form is not uncommon in Utah. Probably the

rarefaction of the air on a plateau 4,000 feet above the sea

level has something to do with its frequency. Artemus's fears

relative to the cordiality of his reception proved to be

groundless, for during the period of his being ill he was

carefully tended. Brigham Young commissioned Mr. Stenhouse,

postmaster to the city and Elder of the Mormon

Church, to visit him frequently and supply him with whatever

he required. One of the two wives of Mr. Townsend, landlord

of the Salt Lake House, the hotel where we stopped was

equally as kind. Whatever the feelings of the Mormons were

towards poor Artemus, they at least treated him with sympathetic

hospitality. Even Mr. Porter Rockwell, who is known

as one of the “Avenging Angels,” or “Danite Band,” and

who is reported to have made away with some seventeen or

eighteen enemies of the “Saints,” came and sat by the bedside

of the sufferer, detailing to him some of the little “difficulties”

he had experienced in effectually silencing the unbelievers

of times past.

“Temperance Hotel.” At the date of our visit, there was

only one place in Salt Lake City where strong drink was

allowed to be sold. Brigham Young himself owned the

property, and vended the liquor by wholesale, not permitting

any of it to be drunk on the premises. It was a coarse,

inferior kind of whisky, known in Salt Lake as “Valley Tan.”

Throughout the city there was no drinking-bar nor billiard

room, so far as I am aware. But a drink on the sly could

always be had at one of the hard-goods stores, in the back

office behind the pile of metal saucepans; or at one of the

dry-goods stores, in the little parlour in the rear of the bales

of calico. At the present time I believe that there are two or

three open bars in Salt Lake, Brigham Young having recognised

the right of the “Saints” to “liquor up” occasionally.

But whatever other failings they may have, intemperance

cannot be laid to their charge. Among the Mormons there

are no paupers, no gamblers, and no drunkards.

“Overland Mail Coach.” From Virginia City to Salt

Lake we travelled in the coaches of the “Pioneer Stage

Company.” In leaving Salt Lake for Denver we changed to

those of the “Overland Stage Company,” of which the

renowned Ben Holliday is proprietor, a gentleman whose

name on the Plains is better known than that of any other

man in America.

“Been in Newgate.” The manner in which Artemus

uttered this joke was peculiarly characteristic of his style of

lecturing. The commencement of the sentence was spoken

as if unpremeditated; then, when he had got as far as the

word “Newgate,” he paused, as if wishing to call back that

which he had said. The applause was unfailingly uproarious.

Travelling through the States, he used to say, “Those of you

who have been in the Penitentiary.” On the morning after

his lecture at Pittsburg in Pennsylvania, he was waited on by

a tall, gaunt, dark-haired man, of sour aspect and sombre

demeanour, who carried in his hand a hickory walking-cane,

which he grasped very menacingly, as addressing Artemus he

said, “I guess you are the gentleman who lect'red last

night?” Mr. Ward replied in the affirmative. “Then I've

got to have satisfaction from you. I took my wife and her

sister to hear you lecter, and you insulted them.” “Excuse

me,” said Artemus. “I went home immediately the lecture

was over, and had no conversation with any lady in the hall

that evening.” The visitor grew more angry, “Hold thar,

Mr. Lect'rer. You told my wife and her sister that they'd

been in the Penitentiary. I must have satisfaction for the

insult, and I'm come to get it.” Artemus was hesitating how

to reply, when the hotel clerk suddenly appeared upon the

scene, saying, “I've a good memory for voices. You are Mr.

Josiah Mertin, I believe?” “I am,” was the reply. “And I

am the late clerk of the Girard House, Philadelphia. There's

a little board-bill of yours owing there for ninety-two dollars

and a half. You skedaddled without paying. Will you oblige

me by waiting till I send for an officer?” I believe that Mr.

Josiah Mertin did not even wait for “satisfaction.”

“The Pacific Railway.” The journey was made in the

winter of 1863-4. By the time these notes appear in print,

the Pacific Railway will be almost complete from the banks

of the Missouri to those of the Sacramento, and travellers will

soon be able to make the transit of over three thousand miles

from New York City to the capital of California, without

leaving the railway car, except to cross a ferry, or to change

from one station to another.

“Brilliant as that of any theatre in London.” Herein

Artemus slightly exaggerated. The colouring of the theatre

was white and gold, but it was inefficiently lighted with oil

lamps. When Brigham Young himself showed us round the

theatre, he pointed out, as an instance of his own ingenuity,

that the central chandelier was formed out of the wheel of

one of his old coaches. The house is now, I believe, lighted

with gas. Altogether it is a very wondrous edifice, considering

where it is built and who were the builders. At the time

of its erection there was no other theatre on the northern

part of the American plateau, no building for a similar purpose

anywhere for five hundred miles, north, east, south, or

west. Many a theatre in the provincial towns of England is

not hald so substantially built, nor one tithe-part so well appointed.

The dressing rooms, wardrobe, tailors' workshop,

carpenters' shop, paint room, and library, leave scarcely anything

to be desired in their completeness. Brigham Young's

son-in-law, Mr. Hiram Clawson, the manager, and Mr. John

Cane, the stage manager, if they came to London, might

render good service at one or two of our metropolitan playouuses.

“Old Ciss.” Here again no description can adequately

inform the reader of the drollery which characterized the

lecturer. His reference to Cicero was made in the most

lugubrious manner, as if he really deplored his death and

valued him as a schoolfellow loved and lost.

“United States Troops.” Our stay in Utah was rendered

especially pleasant by the attentions of the regiment of

California Cavalry, then stationed at Fort Douglas in the

Wahsatch Mountains, three miles beyond and overlooking

the city. General Edward O'Connor, the United States

Military Governor of Utah, was especially attentive to the

wants of poor Artemus during his severe illness; and

had it not been for the kind attentions of Dr. Williams, the

surgeon to the regiment, I doubt if the invalid would have

recovered. General O'Connor had then been two years

stationed in Utah, but during the whole of that time had

refused to have any personal communication with Brigham

Young. The Mormon prophet would sit in his private box,

and the United States general occupy a seat in the dress-circle

of the theatre. They would look at each other frequently

through their opera-glasses, but that constituted their whole

mtimacy.

“A hundred head of Wives.” It is an authenticated fact

that, in an address to his congregation in the tabernacle,

Heber C. Kimball once alluded to his wives by the endearing

epithet of “my heifers;” and on another occasion politely

spoke of them as “his cows.” The phraseology may possibly

be a slight indication of the refinement of manners

prevalent in Salt Lake City.

“Soft Music.” Here Artemus Ward's pianist (following

instructions) sometimes played the dead march from “Saul.”

At other times, the Welsh air of “Poor Mary Anne;” or anything

else replete with sadness which might chance to strike

his fancy. The effect was irresistibly comic.

“That I declined.” I remember one evening party in

Salt Lake City to which Artemus Ward and myself went.

There were thirty-nine ladies and only seven gentlemen.

“Solid Gold.” “Where will the gold be obtained from?”

is a question which the visitor might reasonably be expected

to ask. Unquestionably the mountains of Utah contain the

precious metal, though it has not been the policy of Brigham

Young and the chiefs of the Mormon Church to disclose

their knowledge of the localities in which it is to be found.

There is a current report in Salt Lake City that nuggets of

gold have been picked up within a radius of a few score of

miles from the site of the new temple. But the Mormons,

instructed by their Church, profess ignorance on the subject.

The discovery of large gold mines, and permission to work

them, would attract to the valley of Salt Lake a class of visitors

not wished for by Brigham Young and his disciples. Next

to the construction of the Pacific Railway, nothing would be

more conducive to the downfall of Mormonism than Utah

becoming known as an extensive gold-field.

“A Fancy Sketch.” Artemus had the windows of the

temple in his panorama cut out and filled in with transparent

coloured paper, so that, when lighted from behind, it had the

effect of one of the little plaster churches with a piece of

lighted candle inside, which the Italian image-boys display

at times for sale in the streets. Nothing in the course of the

evening pleased Artemus more than to notice the satisfaction

with which this meretricious piece of absurdity was received

by the audience.

“The Great Salt Lake.” A very general mistake prevaus

among those not better informed that the Mormon capital is

built upon the borders of the Salt Lake. There are eighteen

miles of distance between them. Not from any part of the

City proper can a view of the Lake be obtained. To get a

glimpse of it without journeying towards it, the traveller must

ascend to one of the rocky ledges in the range of mountains

which back the city. So saline is the water of the lake, that

three pailsful of it are said to yield on evaporation one pailful

of salt. I never saw the experiment tried.

“The Moon myself.” Here Artemus would leave the

rostrum for a few moments, and pretend to be engaged

behind. The picture was painted for a night-scene, and the

effect intended to be produced was that of the moon rising

over the lake and rippling on the waters. It was produced in

the usual dioramic way, by making the track of the moon

transparent and throwing the moon on from the bull's eye of

a lantern. When Artemus went behind, the moon would

become nervous and flickering, dancing up and down in the

most inartistic and undecided manner. The result was that,

coupled with the lecturer's oddly expressed apology, the

“moon” became one of the best laughed-at parts of the

entertainment.

“The Endowment House.” To the young ladies of Utah

this edifice possesses extreme interest. The Mormon ceremony

of marriage is said to be of the most extraordinary

character; various symbolical scenes being enacted, and the

bride and bridegroom invested with sacred garments which

they are never to part with. In all Salt Lake I could not find

a person who would describe to me the ceremonies of the

Endowment House, nor could Artemus or myself obtain

admission within its mystic walls.

“They are Horses.” Here again Artemus called in the

aid of pleasant banter as the most fitting apology for the

atrocious badness of the painting.

“Their way to the battle-field.” This was the great joke

of Artemus Ward's first lecture, “The Babes in the Wood.”

He never omitted it in any of his lectures, nor did it lose its

power to create laughter by repetition. The audiences at the

Egyptian Hall, London, laughed as immoderately at it as did

those of Irving Hall, New York, or of the Tremont Temple

in Boston.

“Raw dog.” While sojourning for a day in a camp of

Sioux Indians we were informed that the warriors of the tribe

were accustomed to eat raw dog to give them courage previous

to going to battle. Artemus was greatly amused with the

information. When, in after years, he became weak and

languid, and was called upon to go to lecture, it was a

favourite joke with him to inquire, “Hingston, have you got

any raw dog?”

“On Reginald's breast.” At this part of the lecture

Artemus pretended to tell a story—the piano playing loudly

all the time. He continued his narration in excited dumb-show—his

lips moving as though he were speaking. For

some minutes the audience indulged in unrestrained laughter.

“As high-principled as I am.” The scene was a transparent

one—the light from behind so managed as to give the

effect of the prairie on fire. Artemus enjoyed the joke of

letting the fire go out occasionally, and then allowing it to

relight itself.

“That Lion has a tail.” The lion on a pedestal, as

painted in the panorama—its tail outstretched like that of the

leonine adornment to Northumberland House, was a pure

piece of frolic on the part of the entertainer. Brigham

Young certainly adopts the lion as a Mormon emblem. A

beehive and a lion, suggestive of industry and strength, are

the symbols of the Mormons in Salt Lake City.

“To be continued in our next.” To re-visit Utah, and to

do another and a better lecture about it was a favourite idea

of Artemus Ward. Another fancy that he had was to visit the

stranger countries of the Eastern world and find in some of

them matter for a humorous lecture. While ill in Utah, he

read Mr. Layard's book on Nineveh, left behind at the hotel

by a traveller passing through Salt Lake. Mr. Layard's reference

to the Yezedi, or “Devil worshippers,” took powerful

hold on the imagination of the reader. During our trip home

across the plains he would often, sometimes in jest and sometimes

in earnest, chat about a trip to Asia to see the “Devil

worshippers.” Naturally his inclinations were nomadic, and

had a longer life been granted to him I believe that he would

have seen more of the surface of this globe than even the

generality of his countrymen see, much as they are accustomed

to travel. Within about the same distance from Portland in

England that his own birth-place is from Portland in Maine,

his travels came to an end. He died at Southampton. His

great wish was for strength to return to his home, that he

might die with the face of his own mother bending over him,

and in the cottage where he was born.

Cœlumque

Adspicit et moriens dulces reminiscitur Argos.”

E. P. H.

| Artemus Ward's panorama | ||