| Coupon bonds, and other stories | ||

ARCHIBALD BLOSSOM, BACHELOR.

1. I.

MR. BLOSSOM HEARS BAD NEWS.

MR. BENJAMIN BLOSSOM was guilty of three faults

which his brother Archy, the bachelor, could not forgive:

first, having a family; second, going to California;

and, lastly, dying when he got there.

The news of the lamented Blossom's decease was brought

to Archy one morning, like Cleopatra's asp, with his breakfast.

The surviving brother, unconscious of the sting prepared

for him, comfortably seated himself to nibble the

bread of single-blessedness, spread his landlady's neat white

napkin on his lap, tucking the corners into the armholes of

his waistcoat, stirred his coffee, read the morning paper, ate

three eggs out of the shell with a little ivory scoop, and

finally broke the seal of the feminine-looking envelope beside

his plate.

“I knew there was something deused disagreeable in

that letter!” said Archy, turning first purple and then

pale. “The best I can do, I am always being made a

victim!”

The epistle was from the mother of Benjamin's children;

and in a cramped chirography, and a style full of grammatical

errors, italics, and tears, indicating a good deal of

grief and not much education, it informed the bachelor

that his sister-in-law was a widdow (with two d's), and his

very apt to spoil his breakfast, but for the precaution he

had taken to open the eggs before he did the letter.

Archy walked the room with his napkin, and thought of a

good many things, — poor Ben dying away off there, among

strangers, and, no doubt, in very improper clothes; how he

(the surviving brother) would look in black; and what was

his duty respecting Priscilla and her orphans.

“There is no other way, as I see,” he mused, wiping his

forehead with the napkin, “but to submit, and be a victim!

Think of me, Archibald Blossom, suddenly called to be the

father of four little Blossoms; and a brother to her whose

heart is left destitoot-t, double-o, t, toot!” groaned Archy,

holding the letter up to the light. “Poor woman! poor

woman! no doubt she was too much afflicted to give attention

to her spelling. A brother to her! I wonder she

did n't say a husband, while she was about it!” And Archy

smiled a grim smile in the glass, mentally contrasting his

fastidious habits of life with the disagreeable ties and duties

of paternity.

To the bachelor's love of nicety and sleepless solicitude

for himself was joined an amiable disposition which was forever

getting the other traits into trouble. On the present

occasion he was perfectly well aware, as we have seen, that

he was to be made a victim; nevertheless, even while heaping

reproaches upon the late Benjamin, calling his children

brats, and cursing the man who first invented widows, he

resolved to visit his brother's family, — brushed his wig, colored

his whiskers, packed a carpet-bag, and made other

preparations for the pious pilgrimage. It was the first

time he had ever thought of fulfilling the Scriptural injunction,

“To visit the fatherless and widows in their affliction”;

although it had long been a personal habit of his to keep

himself, literally, “unspotted from the world.”

2. II.

A VISIT TO THE WIDOW AND FATHERLESS.

It was half a day's journey from Archy's residence in town

to the rural locality which he had no doubt was all this

time resounding with the lamentations of the bereaved

family. Arrived at the village hotel, he ordered a room

and supper; and, after the necessary ablutions and refreshments,

and certain studious moments devoted to his attire,

he set out, with his immaculate waistcoat and gold-headed

cane, to walk to the Blossom cottage.

It was Archy's first advent in the place; a chronic dislike

of scenes rustic and domestic having hitherto deterred

him from venturing upon a visit. He was surprised to

find the little town so charming. It was the close of a

pleasant June day; the sunset was superb, the air cool and

sweet, the foliage of the sunlit trees thick and refulgent.

“Really,” said Archy to himself, snuffing the odor of

roses and pinks that breathed from somewhere about a

green-embowered cottage, — “really, and upon my soul, a

man might pass an hour or two in this place quite agreeably!

Young man,” — accosting a village youth, in soiled

shirt-sleeves and patched trousers, who approached, pushing

a loaded wheelbarrow before him on the sidewalk, —

“can you inform me where Mrs. Blossom lives?”

“P'scill Blossom?” said the village youth, setting down

the wheelbarrow and tucking up his shirt-sleeves.

“Mrs. Benjamin Blossom,” replied Archy, with dignity.

“That 's P'scill,” said the village youth, twisting his

mouth into a queer expression, and eying Archy with a

slant, shrewd leer. “You 've come past. Foller me, and

I 'll show ye. Look out for your shins!”

He spat upon his hands, rubbed them together, and once

more addressed himself to the wheelbarrow. Archy stepped

aside and walked behind. The young man turned up to

the fence that enclosed the green-embowered cottage, from

about which breathed the delightful odor of pinks and

roses.

“Wish you 'd jest open that gate,” said he, holding the

wheelbarrow.

Archy, who was unaccustomed to opening gates for

people, stood amazed at this audacity. But the young man

repeating his request, he concluded to take a benevolent

and humorous view of the matter, and, stepping before

the wheel, rendered the service.

“Clear the track now!” And the young man began to

push.

“Hold! take care!” cried Archy, in peril of his legs.

“You scoundrel!” He flourished his cane. But as the

wheelbarrow continued to advance, his alternative was

either to suffer a collision or retreat. Preferring the latter,

he went backward into the yard. Going backward into the

yard, he struck his heel against the border of a flower-bed.

Striking his heel, he tripped, as was natural, and lost his

balance, being unable to recover which, he made a formidable

plunge, falling in the most awkward of all positions.

His cane flew into the air, his hat into the bushes, and instantly

he found himself deeply seated amidst some of the

aforesaid odorous pinks and roses.

“Hello! look out! darnation!” ejaculated the youth of

the wheelbarrow; “tumblin' over them beds! P'scill 'll be

in your hair!” Which last allusion prompted the unfortunate

Mr. Blossom to catch at his wig, that useful article

having found a closer affinity with a rosebush than with

the head to which it belonged.

“Young man!” said Archy, regaining his feet and gathering

within an inch of your life!”

“Do I, though?” and the youth's shrewd leer brightened

into an expression of sparkling fun. “I ha'n't done noth'n',

only showed you where we live.”

“Who cares where you live?” retorted Archy, pale and

agitated, hastily brushing his clothes. “You remorseless

idiot! I inquired for Mrs. Blossom's house.”

“Wal, a'n't I showin' ye? This is our house; I 'm her

cousin,” said the youth. “I a'n't to blame, as I see, for

your goin' on to the bed backwards.”

“I must always be a victim!” growled Archy, using his

handkerchief for a duster. “Young man, I am Benjamin

Blossom's brother, and I wish to see Mrs. Blossom.”

“Jimmyneddy!” cried the youth, “be ye, though?

Darned if I did n't think you was the new minister! I

would n't have done it — I mean, I did n't mean to — lemme

brush off the dirt!” And he fell to using his unwashed

hands about Archy's person with a freedom more alarming

than any quantity of unadulterated dirt. The poor bachelor

was endeavoring to defend himself when a young

woman appeared, coming out of the house, and inquiring

eagerly what was the trouble.

A young woman, — she might have been forty; but she

was still fresh and good-looking, with a plump figure, hazel

eyes, a genuine complexion, teeth that were teeth, beautiful

hair of her own, and a pleasing smile. The smile beamed,

and at the same time the hazel eyes shone through tears,

when the youth of the wheelbarrow announced Mr. Blossom's

brother

“O dear, good brother Archy!” she exclaimed, with

something between a sob and cry of joy.

“My afflicted sister — ” began Archy, who had composed

a pathetic little speech, appropriate to the occasion.

made a movement indicative of falling into his arms, he

opened them. Seeing them opened, she could do no less

than fall into them. So the afflicted couple embraced, and

Mrs. Benjamin Blossom wept upon Mr. Archibald Blossom's

shoulder.

“To think we should meet, for the first time since my

marriage, on such an occasion!” murmured Mrs. Blossom.

“You have changed very little since that time,” said

Archy, gallantly, regarding her at arm's-length.

“Brother Archy,” faltered Priscilla, wiping her eyes,

“this is my cousin, Cyrus Drole.” And the bachelor was

formally introduced to the youth of the wheelbarrow.

Cyrus offered to shake hands, and Archy, after some

hesitation, gave him two fingers.

“And these,” said Mrs. Blossom, “are my — his — his

children!” — meaning her late husband's, not the grinning

Cyrus's. She burst into tears, and catching up the youngest

of the lamented Benjamin's progeny, as they came running

out of the house, almost smothered it with kisses.

Archy took out his handkerchief again, wiped first the

two fingers Cyrus had shaken, and then his eyes.

“Poor little dears!” he said, much affected. “How

could Benjamin ever leave for a moment so — so interesting

a family!”

“Benjie — Phidie — Archy,” Mrs. Blossom called the

names of the three older children according to their ages,

“this is your uncle, — your kind, dear uncle, — your father's

only brother, and now all the father you have left!” More

sobs, of the choking species. “Kiss your good uncle!”

“Dear little ones — yes!” said Archy, “give your uncle

a kiss! (I am going to be a victim, — I know I am!”

he added, in a parenthesis, to himself.) “There! there!

there!” embracing the three children in succession, but

touched his, and then putting them immediately away. He

was congratulating himself on having done up this little

business so handsomely, when Mrs. Blossom reminded

him.

“This is the youngest, — the baby, brother Archy; don't

forget the baby!”

“Bless his little heart, no,” said Archy, gayly fencing

with his forefinger; “tut-tut! cock-a-doodle-do! Really,

and upon my soul, what a fine boy it is!”

“But it 's a girl,” said Priscilla, hugging the frightened

little thing to keep it from crying.

“O, indeed! my mistake! But it 's all the same till they

get their baby frocks off,” replied Archy. And the procession

moved into the house, Cyrus Drole bringing up the rear.

Priscilla, hastily emptying the large rocking-chair of a cat,

two kittens, and a doll, offered her brother-in-law a seat.

“That 's my pussy!” said Benjie (young Blossom number

one, æt. 7).

“My doll!” screamed Phidie (number two, æt. 5).

“Mamma's chair!” cried little Blossom number three;

and before Archy the uncle could sit down, Archy the

nephew had scrambled into it.

“Archy, my dear,” remonstrated the mother, “get down

and give his uncle the chair.”

But Archy, laying hold of the arms with both hands, began

to rock with all his might, his bright eyes glistening,

and his curls shaking merrily about his cheeks. Thereupon

the uncle quietly helped himself to another chair,

which Priscilla hastened to dust with her apron before she

would suffer him to sit down.

“Say, P'scill!” cried Cyrus, who had gone into the

kitchen to wash himself; and he appeared at the sitting-room

door, rubbing his hands in a profuse foam of soft-soap

Uncle Archy for a minister?”

“He calls me uncle too!” inwardly groaned the bachelor.

“You have n't been to tea, I suppose?” observed Priscilla,

setting out the table, and putting up a leaf. Archy

said he had taken tea at the hotel. “Indeed! Are you

sure? That was n't very kind in you, brother Archibald!”

The young widow was reluctantly putting down the leaf,

with many expressions of regret, when all were startled by

a sound of shivered glass, and Phidie (abbreviation of Sophia)

uttered a cry of alarm.

“O ma! look at Cilly!” (Blossom number four, æt. 2,

named after her mother.) She had got Uncle Archy's

cane, and had tested the virtue of the pretty gold head by

putting it through a window-pane.

“Why, Cilly! what has she done?” exclaimed her mother.

Cilly began to cry. At that moment young Archy

rocked over. Another cry. The benevolent bachelor

sprang to lift up his namesake from beneath the overturned

chair, and, stooping, struck his head against Phidie's

nose. Third cry added to the chorus. Mrs. Blossom,

meanwhile, was occupied in running over Benjie, whose

fingers she had previously pinched by too suddenly dropping

the table-leaf when the alarm was given. At the same

time Cyrus, with his soapy hands, ran to the rescue, and

took the cane from the affrighted and screaming Cilly.

“What did I tell you, Archibald Blossom?” said the

bachelor to himself. “I knew perfectly well you would be

a victim!” And stepping back upon a kitten's tail, he

elicited a squall of pain from the feline proprietress of

the pinched appendage, and a mew of solicitude from the

maternal cat.

For a few minutes the domestic confusion in the cottage

had ever conceived. But the tumult soon passed; the

broken glass was picked up; the cane (with the streaks of

Cyrus's soapy fingers on it) set away; Phidie's nose washed,

which had bled; and the Blossoms number three and four

put to bed, after saying their prayers and kissing, with

oozy faces, — or, rather, kissing at, — their Uncle Archy.

Benjie and Phidie were suffered to sit up half an hour

longer, upon condition that they should behave themselves;

at the expiration of which time they also said their “Now

I lay me” and “Our Father” at their mother's knee,

greatly to the edification of their uncle, whom they afterward

kissed at, with a good-night, on going to bed. Cyrus,

in the mean time, had gone to spend his evening at the

village stores and bar-rooms; and now the widow and the

surviving brother of the late Benjamin Blossom were left

alone together.

3. III.

MR. ARCHIBALD AND MRS. BENJAMIN.

The cottage was quiet; a single lamp was lighted; the

grief-stricken widow took a seat rather near the surviving

brother. As they discussed the lamentable news the last

steamer had brought, she drew her chair closer still, allowing

her head, weighed down by affliction, to droop sympathetically

toward his shoulder. Archy was deeply troubled.

“I am more than ever convinced that I shall be a

victim,” he thought, as he glanced sideways at his companion;

“but, really, and upon my soul, there 's something

pleasing about her!”

In the abandonment of grief she let her hand drop

upon his knee. She was too much absorbed by her sorrows

to think of removing it. Archy experienced a very

strange sensation. He had never in his life known anything

to produce precisely such an effect as that hand

upon his knee; and he wondered if his companion was

really aware that it had gone a-visiting. Then Archy suffered

his own hand (in the abandonment of grief) to drop

near the widow's. There is something magnetic in hands.

They attract by laws more subtle than the loadstone's.

Two peculiarly charged hands upon the same knee must

inevitably touch. Archy's palm lay in the most careless

manner upon the back of Priscilla's hand. Gradually his

fingers tended to encircle hers; an encouraging movement

on her part, then a nestling together of thrilling

palms, then an ardent mutual pressure, — and Archy found

himself in a position which he would have deemed utterly

impossible an hour ago. With that soft, warm, flexible, electric

conductor pouring its vital streams into his veins, he

comprehended, as never before, how men are entrapped into

matrimony. He saw how his brother (the lamented Benjamin)

had been entrapped, and forgave him. It was Archy's

left hand that clasped Priscilla's left, she sitting upon his

right; and now his other arm (all in the abandonment of

grief) fell from the top of her chair and lodged near her

waist. Her right hand met his, — not to remove it, but to

draw it ever so gently about her. At the same time her

head, which had been drooping so long, touched his shoulder.

Silence, and two deep breaths. Very natural: he

had lost a brother, she a husband; and this was consolation.

“My dear sister,” said Archy, “you must not let — ah

— circumstances trouble you. I have a little property, —

enough to keep me comfortable, — and I have put by a little

always felt sure Benjamin's projects would turn out in

some such way; and, you see, you are not to want for anything,

Priscilla —”

“O dear, dear Archy! bless you!” said the widow,

with so much emotion that tears were drawn right out of

Archy's eyes. “But it is n't money I want! True, I have

four children, — they are friendless orphans, — I am poor;

but I can work for them with my last breath. It is n't

money I want! but sympathy, — a brother's love, — somebody

to talk to that knew him, — to keep my heart from

breaking while my dear children live! O, promise me

that!” She clung to Archy. He knew he was a victim,

but he also perceived that to be a victim might be sweeter

than he had deemed.

4. IV.

CYRUS.

At this interesting moment the gate clanged, a shuffling

of shoes on the stoop-floor followed, and Cyrus Drole

walked unceremoniously into the room.

“I am saved!” thought Archy. But it must be confessed

he would have preferred not to be saved quite so

soon. His chair, as Cyrus entered, was at least a yard and

a half from the widow's, and their hands looked perfectly

innocent of contact. The hero of the wheelbarrow might

have perceived that he was expected to withdraw from the

sacred precincts of grief; but he coolly took a chair and

sat down, with his hat on.

“Everybody is askin' about Uncle Archy; you 'd think

the President had come to town!” said Cyrus, tipping

“But did n't they all la'f when I told about takin'

him for a minister, and runnin' him on to the beds!” And

Cyrus chuckled under his hat-brim, hugging his elevated

knees.

The two votaries of grief heard these ill-timed words in

appropriate solemn silence. Nobody else appearing inclined

to talk, Mr. Drole “improved” the occasion. He quoted

popular remarks concerning the surviving Mr. Blossom.

Elder Spoon's daughter thought he walked “drea'ful stiff”;

Miss Brespin, the dressmaker, declared that he winked at

her as he passed her window. Archy writhed at this stinging

imputation, but contented himself with frowning upon

Cyrus.

“Brother Archy don't want to hear all this, Cyrus,”

interposed the serious-faced Priscilla.

“Jeff Jones said he looked like a horned pout with his

white-bellied jacket on!” continued Cyrus. “Cap'in Fling

wanted to know if he was an old bach; an' when I said he

was, says he, `I 'll bet fifty dollars,' says he, `he 'll marry

the widder!' `If he does,' says Old Cooney, says he, `he

won't look so much as if he 'd just walked out of a ban'box

time he 's been married a month,' says he. I did n't say

nothin', but la'ft!”

“Cyrus Drole!” cried the indignant widow, “if you

can't behave yourself, you shall go straight to bed. What

must Brother Archy think of your impudence?”

“I guess he 'll think it 's natur'!” laughed Cyrus. “I

s'posed you would n't mind, bein' we 're all cousins.”

Archy had arisen. He inquired, in some agitation, for

his hat and cane.

“Why, Brother Archy!” said Priscilla, alarmed, “where

are you going?” Archy explained that he had engaged

his lodging at the hotel, where his baggage remained. “I

And the widow's tearful eyes looked up pleadingly. “Do

stay with us! Cyrus shall go for your carpet-bag!”

Archy said something about “giving trouble.” She reproached

him tenderly. It would be a comfort, she assured

him, to know that he was beneath her roof; and

it would soothe her loneliness to remember the pathetic

circumstance after he was gone.

“I am a victim!” thought Archy; but he could not

resist such winning entreaties. Cyrus was despatched for

the carpet-bag. He was absent not much more than five

minutes; and on his return, placing the article of luggage

on the table, he seated himself, tipped against the wall,

with his hat on, as before.

“Any time you wish to retire, Brother Archy, — ” suggested

the widow's softened voice.

Archy cast a scowling glance at Cyrus (who appeared

immovable), and replied that he felt the need of rest after

his long journey.

“Don't hurry on my account,” said Cyrus. “I jest

as lives set up and keep ye comp'ny!”

Unseduced by this generous offer, Archy took his

carpet-bag and proceeded, under the widow's guidance,

to the spare bedroom. It was a neat little chamber, with

a rag-carpet on the floor, and cheap lithographs in cheap

frames on the wall. The lamp was placed on the white-spread

stand, and the carpet-bag on a chair. Archy gave

the widow his hand.

“Good night, sister!” Priscilla wept. “Afflicted one!”

said Archy, drawing her near him. He put down his lips;

she put up hers. At that affecting moment a chuckle was

heard. Both started.

“Ye 'fraid of muskeeters, Uncle Archy?” said Cyrus,

putting his head in at the door.

Archy had never in his life felt so powerful an impulse

to fracture somebody's cervical column. Had there been

a weapon at hand, Cyrus would have suffered. As it was,

he advanced with impunity into the room.

“'Cause, ef you be, there 's some in this room that long!”

he added, measuring off a piece of his hand. “Ain't they,

P'scill?”

“Cyrus Drole! there is n't a mosquito in the house, and

you know it!” exclaimed the widow. “What do you talk

so for?”

“They 've got some over to the tavern bigger yit,” said

Cyrus, seating himself astride a chair, and resting his

arms on the back. “They hitched six on 'em to a handcart

t'other day, and they ripped it all to flinders!”

“Come, Cyrus,” expostulated the widow, “you 've no

business here; brother wants to go to bed.”

“He won't mind me; I 'll keep him comp'ny till he

wants to go to sleep. You need n't stop, if you don't

want to!”

Thereupon the widow hastily withdrew, calling upon

him to follow. Cyrus rocked to and fro, in his reversed

position, appearing perfectly and entirely at home. Archy

regarded him sternly.

“What d'ye haf to pay for them kind o' boots?” asked

Cyrus. “Pegged or sewed? hey?” No reply. “Psho!

what 's the matter? You look as though you 'd forgot

suth'n'!”

“Young man,” said Archy, loftily, “will you have the

kindness to postpone the entertainment of your personal

presence and conversation to some remote future period?

In other words, will you oblige me by leaving this room?”

“Don't feel like talkin', hey? Wal, I d'n' know but I

will, seein' it 's you!” Cyrus, rising deliberately, knocked

over his chair, set it up again, and walked slowly to the

Oh! you 're in a hurry, be ye?”

Seeing Archy advancing upon him with a somewhat

ferocious look, he quickened his step, and with a grin of

insolent good-nature dodged out of the room.

5. V.

A. B. BECOMES A VICTIM.

Archy shut the door, and placed two chairs against it,

— there being no lock, — pulled off the said boots, hung

his wig on the bedpost, and in due time retiring, thought

of the widow, and called himself a victim, until he fell

asleep; when he dreamed that he was wedded to a spectre,

in soiled shirt-sleeves and patched trousers, and had nine

children, all of whom were born with little wheelbarrows

in their hands.

He was awakened by shouts of childish laughter. He

thought of his dream, rubbed his eyes, recognized his wig

on the bedpost, and remembered where he was. The

laughter proceeded from an adjoining room, where the

little Blossoms slept. Archy took his watch from beneath

the pillow, and discovered that he had been robbed of his

rest three hours earlier than his usual time for rising.

“I 'm always being a victim!” he said, with a yawn.

“But I suppose it 's the custom in the country to get up

at five. It will be such a novelty, I 'll try it for once.”

So Archy arose, dressed, put on his hat, found his

gold-headed cane (with the marks of Cyrus's soapy fingers

on it), and went out to walk. There was a freshness and

beauty in nature which afforded him an agreeable surprise.

“Really, and upon my soul,” he said, “I had quite

forgotten that mornings in the country were so fine! One

might enjoy an experience of this kind once or twice a

year very well indeed.”

Priscilla was occupied in dressing the children when

he went out. On his return she was preparing breakfast.

He was curious to see how she would look by daylight;

and he was conscious of a slight agitation as he entered

the room. Her occupation, together with the heat of the

kitchen stove, had given her a beautiful color; and the

tear and smile with which she greeted him completed the

charm. Thus the day began. Archy, who had intended

to return on the first train to town, stayed until the afternoon.

He then found it impossible to turn a deaf ear to

the widow's entreaties, who urged him to remain another

night beneath her roof. He delayed his departure another

day, and still another night; and ended by spending

a week with the widow, Cyrus, and the children, — a week

whose history would fill a volume. What we have not

space to detail here the reader's imagination — it must be

vivid — will supply.

At last the bachelor returned to town. He had long

wished to go, and wished not to go. His experiences had

been both sweet and terrible; and to depart was as excruciating

as to remain. In tearing himself away he left

behind a lacerated heart, which Mrs. Priscilla Blossom

retained, and in return for which she sent him letters full

of affection and bad spelling. It is singular how soon

a tender interest in persons invests even their faults with

a certain charm. Not a month had elapsed before Archy

had learned to love those innocent little errors of orthography

and construction as dearly as if the i's she neglected

to dot were the very eyes which he had so often

seen weep and smile.

“Really, and upon my soul,” said Archy, one morning,

after kissing her letter at least twice for every precious

error it contained, “she is a delightful creature; and, by

Jove, I 'd marry her — I would, truly — if — if it was n't

for being a victim!”

A strange unrest — to use a perfectly unhackneyed

expression — agitated his once placid bosom. Appetite

and flesh forsook him; his landlady observed that her

bountiful repasts no longer filled him; his tailor, that

he no longer filled his clothes. His friends shook their

heads and said, “The Blossom has been nipped by untimely

frost!”

At length, yielding to destiny, he again disappeared

mysteriously from town. It is supposed that he visited

Priscilla. He was absent a week. He returned, bearing

a still larger burden of unrest than he had carried away.

In short — to sum up the tragical result in one word —

Archy was a victim, and he knew it!

How it all happened, poor Archy could never tell; and

if he could not, how can his biographer? As early as the

middle of October he had written to Priscilla irrevocable

words, ordered a wedding suit of his tailor, bought a new

wig, and purchased a trunkful of presents for his future

wife and children. The 11th of November was fixed

for the fatal event. On the night of the 9th he slept

not at all, but filled the hours with wakefulness and sighs.

“O Benjamin,” he said, “if you had only lived! I wish

I had never gone up there! But it is too late to retract!

It would break poor dear Priscilla's heart! I am quite

sure she would die of grief! I must go through with it

now, — I see no other way!” Mrs. Brown wondered what

made her lodger groan so in his sleep.

On the other hand, Archy endeavored to console himself

by reasoning thus: “It was n't in human nature to

only doing my duty. I should have the family to support

any way. I can keep them in the country, and spend as

much time in town as I choose. I shall probably spend

all my time in town, with the exception of now and then

a few days in summer. Though really, and upon my soul,

if it was n't for Cyrus and the children I think I could be

very happy with Priscilla.”

He sank into a half-conscious state, and fancied himself

pursuing a wild, sweet, dangerous road, with two figures

whirling in a dance before him, one beautiful and bright,

but nearly enveloped in the other's black, voluminous

robes. One was Happiness, the other Misery; and so

they led him on, until the former quite disappeared, and

the latter, grim, inexorable, whirled alone. He awoke

with a start just as the hideous creature reached forth a

skeleton hand to claim him as a partner; and once more

Mrs. Brown wondered what made her lodger groan in

his sleep.

Archy was expected on the afternoon of the 10th, and

Cyrus was at the railroad station to meet him when the

train came in. The surviving brother felt not only like a

victim, but also very much like a culprit, when he stepped

from the cars, a spectacle to the group of loungers.

“Haryunclarchy?” (that is, “How are you, Uncle

Archy?”) cried Cyrus, familiarly advancing to shake

hands. “Got along, have ye? P'scill 's been drea'ful

'fraid you would n't come.” A broad grin from Mr. Drole.

Laughter and significant looks from the crowd. Embarrassment

on the part of Mr. Blossom.

“Where 's the carriage?” whispered the future bridegroom,

who, anticipating this scene, had directed that a

decent conveyance should be in waiting for him on his

arrival.

“Could n't git no kind of a one,” said Cyrus, in a loud

tone of voice. “Jinkins 's usin' hisn; Alvord's hoss 's lame;

Hillick, that keeps the tavern, had let hisn; I told 'em

you was comin', and I did n't know what I should do; but

not a darned thing in the shape of a carriage could I scare

up. So I concluded you could walk over to the house, —

guess you ha'n't quite forgot the way; and I 've brought

my wheelbarrer for your trunks.”

“Always a victim!” muttered Archy, red and perspiring,

perhaps at the recollection of his first adventure with

the wheelbarrow. He would have given worlds — as the

romance writers say — had he never set foot in the village.

But retrogression was now impossible. He hastily

pointed out his baggage with his gold-headed cane, and

walked up the street. He had not proceeded twenty

yards when Cyrus came after him, running his wheelbarrow

on the walk, and shouting to the retiring loungers

to “clear the track.” He pushed his load of trunks to

Archy's heels, and there he kept it, occasionally grazing

his calves with the wheel, until the exasperated bridegroom

stepped aside and stopped.

“Go on!” he said, hoarsely.

“Never mind; I a'n't pa'tic'lar!” replied Cyrus, setting

the wheelbarrow down, and spitting on his hands.

“I jest as lives you 'd go ahead. Whew! makes me

blow!”

Archy raised his cane, but forebore exercising it upon

the young gentleman's back (as justice seemed to require)

in consequence of the publicity of the scene. He walked

on. The wheelbarrow followed, again at his heels. And

thus the bridegroom traversed the village, the head of a

procession which caused a general expansion of risible

muscles and a compression of noses upon window-panes

as it passed.

“By the furies!” thought Archy, “I can't go through

with it! I 'll put a stop to the insane proceeding at

once! I 'll make some excuse; I 'll say I 've heard from

California and Benjamin is n't dead. That would n't do,

though; Priscilla 's had a letter from the friend who

received his parting breath. I 'll tell her — I 'll tell her

I 've got another wife. Then she 'll reproach me, and

what shall I say? Say I thought my wife was dead, but

she 's turned up again! That won't do, though, — I

can't lie.”

“Look out for yer legs!” cried Cyrus. They had

passed the gate. Archy was met by Mrs. Blossom and

four little Blossoms, soon to be all his own. Priscilla

clung to his neck, Benjie to his hand, Phidie to his coat-tails,

leaving the lesser Blossoms each a leg.

“I am doomed!” thought Archy. He assumed a gayety,

though he felt it not; opened his heart and his trunk;

distributed presents; received a good many more thanks

and kisses than he wanted; withdrew to the solitude of

his chamber; conferred with Priscilla, who followed him

thither, and whom he found, after all his doubts and despair,

to be the dearest and best of women.

He came out brighter than he had gone in; taking his

seat at the tea-table with Blossoms three and four on each

side and Priscilla opposite. The children had quarrelled

to sit next their uncle, and that rare indulgence had been

granted to the youngest two. Little Archy was barefoot,

and he persisted in rubbing his toes against big Archy's

trousers. Little Cilly (Blossom number four) sprinkled

him with crumbs, buttered his coat-sleeve, and tipped

over his teacup. Archy (the uncle) was beginning to

have very much the air of a parent.

The presents had so much excited the children that the

house that evening was a perfect little Babel. “And this

Cyrus was practising upon a new fiddle, in the kitchen,

and nothing could silence his horrible discords. The

domestic — a recent addition to Mrs. Blossom's establishment

— let fall a pile of dishes, deluging the threshold

with fragments. Benjie upset the table with a lamp and

pitcher, which saturated the carpet with oil and water.

Phidie and Archy quarrelled, and cried an hour after they

had gone to bed. Number four was sick, in consequence

of eating too much of Uncle Archy's candy, and had to

be doctored. Priscilla was harassed and — shall we confess

it? — cross. Add to the picture the melancholy coloring

of the season, — imagine the dreary whistling of the

November wind, and the rattling of dry leaves and naked

boughs, — and you have some notion of a nice, comfort-loving

old bachelor's reasons for homesickness.

Archy retired to his room. “I can't go through with

it! It 's no use! I 'll break it to Priscilla — gradually —

but I 'm resolved to do it! Suppose I make believe

I 'm insane, and tear things? Insane! I 've been insane!

O Benjamin —”

Rap, rap! gently, at the door. “There she is!” said

Archy. “Now, Blossom, be a man!” He opened; Priscilla

entered. She observed his excited mien with a look

of alarm.

“Dear Archy! what is the matter?”

What a wonderful influence there is in woman's eyes, a

ripe lip reaching up to you, and an arm about your neck!

Archy was afraid he was going to be shaken.

“Priscilla!” he said, with a tragic air, “I 've had a

horrid thought! Suppose — suppose Benjamin should

still be alive! and should come home! and find me — me

— a usurper of his happiness!”

“O Archy!” articulated Priscilla, with strong symptoms

of fainting, “spare me! spare me!”

“Of course it is n't reasonable to suppose such a thing,

— but,” stammered Archy, “is n't our marriage hasty,

— premature? Not six months after the news of his

death, — though, to be sure, he had then been dead four

months, and that makes ten. But would n't it, after all,

be wise to postpone our bliss, — say till spring?”

“If you leave me,” said Priscilla, “I shall die!” She

closed her eyes, drooping tremulously in his arms; and

the scene would have been very romantic indeed but for

the plumpness of her figure and the laws of gravitation,

which united in compelling him to ease her down upon

a chair. “But go!” she added, “go! you do not love me!”

“Really, and upon my soul, I do!” vowed Archy,

greatly moved. “Priscilla, I adore you!”

“Then don't — don't break my heart!”

His resolution was melted; he saw that either Priscilla

or himself must be a victim. “I 'll be one myself,” he

thought; “I 'm used to it!” And he said no more of

postponing their conjugal felicity.

We read of prisoners sleeping soundly on the eve of

their execution. So Archy slept that night. The wedding

was appointed for the next morning. The bridegroom

awoke at half past six. It was cold and rainy. He

looked out upon the dismallest scene, — dark and dreary

hills, a deserted street, dripping and shivering trees, dead

leaves rotting upon the ground.

“I have brought my razor with me,” said Archy;

“really, and upon my soul, I think the best thing I can

do is to cut off the wretched thread of my existence,

just under the chin!”

Already the children were laughing and screaming in

the next room, and Cyrus's fiddle squeaked in the kitchen.

Archy got up, took his razor, deliberately honed it, uncovered

his throat, and — with a firm hand — shaved himself.

6. VI.

THE WEDDING DAY, AND WHAT FOLLOWED.

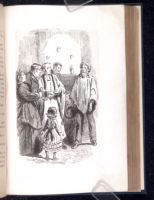

The marriage ceremony was to take place at nine

o'clock, without display; only the clergyman and two

other witnesses were to be present, and the happy pair

were to take the cars at ten for a little journey. Two

bridesmaids came in the rain, at eight o'clock, to dress the

bride. She had already put upon the children their neatest

attire, charging them to remain in the house, and keep

themselves dry and clean. The arrival of the clergyman

was prompt. Nine o'clock struck, — a knell to Archy's

heart. At the fatal moment he appeared; he was handsomely

dressed; he was pale, but firm. No martyr ever

approached the stake with greater fortitude than he displayed

on standing up beside Priscilla, in the little parlor,

with the clergyman facing them and the witnesses waiting.

At this critical moment, Cyrus, who had gone to secure

a conveyance for the wedding party, rushed into the room.

“You, sir,” said the clergyman, addressing Archy, “solemnly

promise to take this woman —”

“Guess you better wait half a jiffy!” cried Cyrus, flirting

his wet cap.

“To be your lawful wife,” added the clergyman.

“Somebody else to come,” added Cyrus; “he 's 'most

here; I run ahead to tell ye to stop.”

“Hush, Cyrus!” whispered the bride.

“To love, honor, and obey,” said the clergyman, growing

confused, “until death do you part —”

“He 'd jest come in on the cars,” interpolated Cyrus.

“Promise,” said the clergyman to Archy, who stood

staring.

“To obey?” faltered Archy.

“Did I say obey? No matter; it 's a mere form —”

“I guess he 's from Caleforny!” cried Cyrus; “mebby

's he 's got news.”

“From California!” uttered Archy, with a gleam of

hope. “Wait; what does the fellow mean? Who — where

is this man?”

“I d'n' know; I never saw him afore; but here he

comes!” said Cyrus. The rascal grinned. Priscilla looked

wild and distressed. Archy believed it was one of Cyrus's

miserable jokes, but resolved to make the most of it.

“Shall I proceed?” inquired the clergyman, who had

quite forgotten where he left off. The gate had previously

clanged; doors had been opened; and now, to the astonishment

of all, a stranger put his head into the room.

He wore a Spanish sombrero, a shaggy coat, and an immense

red beard. As all turned to look at him, he advanced

into the room.

“Stranger!” cried the excited Archy, “who — how —

why this interruption?”

“What is going on?” asked the Californian, in a suppressed

voice.

“Nothing — only — getting married a little,” replied

Archy, excited more and more. “You are welcome, sir,

welcome! but if you have no business —”

“I have business!” The intruder removed his wet

sombrero. “Priscilla! Archibald!”

“Benjamin!” ejaculated Archy, springing forward upon

the clergyman's corns.

“My husband!” burst from the lips of the bride; and

she threw up her arms, swooning in the traveller's damp

embrace. Archy, quite beside himself, ran over the children,

and flung his arms frantically about the reunited

pair.

“I be darned,” said Cyrus, flinging his cap into the

corner, “if 't a'n't Ben Blossom come to life again!”

“Just stand off,” cried Benjamin, sternly, “till we have

this matter a little better understood.”

“I don't object,” replied Archy, brushing himself, “for,

really, and upon my soul, you are very wet!”

Priscilla was restored to consciousness (which, if the

truth must be confessed, she had not lost at all), explanations

were made, and the husband's ire appeased. He,

on his part, maintained that he had not been dead at all;

that the treacherous friend who reported him so had indeed

deserted him when he was in an extremely feeble

condition at the mines, leaving him to perish alone, of

sickness and want, in the dismal rainy season; that he

(Mr. Blossom) had lived, so to speak, out of spite, finding

shelter in a squatter's hut, digging a little for gold, returning

to the seaboard, crossing the Isthmus, and finally

reaching home (with less than half the money he had carried

away) sooner than any letter, mailed at the earliest

opportunity, could have arrived. He seemed rejoiced to

get back again; kissed the children; shook hands with

the neighbors; and, finally, supporting his wife upon one

arm, while he gave Archy a fraternal embrace with the

other, frankly forgave them the little matrimonial proceeding

we have described.

The truth is, Priscilla had expressed her joy at his return

with a spontaneity and emphasis which left no doubt

of her sincerity. Archy felt one pang of jealousy at this;

but it was evident enough that his satisfaction at seeing

Benjamin was unfeigned.

“We are brother and sister again now, Archy?” said

Priscilla, offering him her hand.

“We are nothing else, I am happy to say!” replied

Archy, overflowing with good humor.

“I must beg your pardon, Archy,” said Ben, “for taking

away your bride.”

“Really, and upon my soul,” cried Archy, magnanimously,

“I relinquish her — under the circumstances —

with joy! Take back your family, Ben! Here are the

children, good as new. I give 'em up without a murmur.

Heaven forbid that I should wish to rob my brother of

his treasures!” Archy's self-denial was beautiful.

“S'pos'n' — s'pos'n',” giggled Cyrus, “he had n't come

till to-morrer, an' found there 'd been a weddin'! an' nobody

but me an' the children left to hum!”

This ill-timed speech proved very unpopular, and Cyrus

was hustled out of the room. The wedding having failed

to take place, there was no wedding tour.

Archy remained, and made a visit at his brother's; experiencing

unaccountable sensations upon witnessing the

unbounded happiness of Priscilla. How she could so easily

give up a well-dressed gentleman like himself (after all

her professions, too!) and show such preference for a

rough, bearded, unkempt, half-savage Californian, puzzled

his philosophy. The sight became unendurable. So that

afternoon he packed up his luggage and took leave of the

happy family, turning a deaf ear to all their entreaties,

and setting out, under painful circumstances and a dilapidated

umbrella, to walk to the cars. Cyrus accompanied

him, transporting his trunks upon the celebrated wheelbarrow.

At the station Mr. Drole brought Archy the

checks for his baggage, and gave him his good-by, together

with a little tribute of sympathy.

“I swanny,” said Cyrus, “'t was too bad anyhow you

can fix it! But I would n't give up so; mebby you 'll

have better luck next time.”

“Always a victim!” muttered Archy, taking his seat in

the cars. Cyrus got upon his wheelbarrow, and whistled

arm. The bachelor (still a bachelor) thanked Heaven

when the cars started, and so returned to his elegant

single lodgings in town.

But he was no longer the cheerful, contented bachelor

of other times. An affectionate letter from Mrs. Blossom,

in which she hoped he would find another widdow (with

two d's), and be hapy (with one p), served only to keep

alive the fires that had been kindled in his once cool

breast. He began to seek female society; grew studious

of fair faces; and, to the astonishment of his friends,

within a year both Priscilla's wish and Cyrus's prediction

touching better luck were realized. Archy had found another

widow; who, although perhaps not quite so charming

a creature as she who had first aroused him from

apathetic celibacy, proved, nevertheless, quite as sincere a

woman, as true a wife, and as devoted a mother of her

little Blossoms. They occupy a handsome little cottage a

few miles out of town; where the late bachelor, now the

blessed husband and father, finds wedded life so entirely

to his liking, that he often assures Mrs. Blossom that really,

and upon his soul, the most fortunate day of his life was

when she made him a victim.

| Coupon bonds, and other stories | ||