| Coupon bonds, and other stories | ||

NANCY BLYNN'S LOVERS.

WILLIAM TANSLEY, familiarly called Tip, having

finished his afternoon's work in Judge Boxton's

garden, milked the cows, and given the calves and pigs

their supper, — not forgetting to make sure of his own, —

stole out of the house with his Sunday jacket, and the

secret intention of going “a sparking.”

Tip's manner of setting about this delicate business was

characteristic of his native shrewdness. He usually went

well provided with gifts; and on the present occasion,

before quitting the Judge's premises, he “drew upon” a

certain barrel in the barn, which was his bank, where he

had made, during the day, frequent deposits of green corn,

of the diminutive species called tucket, smuggled in from

the garden, and designed for roasting and eating with the

Widow Blynn's pretty daughter. Stealthily, in the dusk,

stopping now and then to listen, Tip brought out the little

milky ears from beneath the straw, crammed his pockets

with them, and packed full the crown of his old straw hat;

then, with the sides of his jacket distended, his trousers

bulged, and a toppling weight on his head, he peeped cautiously

from the door to see that the way was clear for an

escape to the orchard, and thence, “'cross lots,” to the

Widow Blynn's house.

Tip was creeping furtively behind a wall, stooping, with

one hand steadying his hat and the other his pockets,

when a voice called his name.

It was the voice of Cephas Boxton. Now if there was a

person in the world whom Tip feared and hated, it was

“that Cephe,” and this for many reasons, the chief of

which was that the Judge's son did, upon occasions, flirt

with Miss Nancy Blynn, who, sharing the popular prejudice

in favor of fine clothes and riches, preferred, apparently,

a single passing glance from Cephas to all Tip's gifts

and attentions.

Tip dropped down behind the wall.

“Tip Tansley!” again called the hated voice.

But the proprietor of that euphonious name, not choosing

to answer to it, remained quiet, one hand still supporting

his hat, the other his pockets, while young Boxton, to

whom glimpses of the aforesaid hat, appearing over the

edge of the wall, had previously been visible, stepped

quickly and noiselessly to the spot. Tip crouched, with his

unconscious eyes in the grass; Cephas watched him good-humoredly,

leaning over the wall.

“If it is n't Tip, what is it?” And Cephas struck one

side of the distended jacket with his cane. An ear of corn

dropped out. He struck the other side, and out dropped

another ear. A couple of smart blows across the back succeeded,

followed by more corn; and at the same time Tip,

getting up, and endeavoring to protect his pockets, let go

his hat, which fell off, spilling its contents in the grass.

“Did you call?” gasped the panic-stricken Tip.

The rivals stood with the wall between them, — as ludicrous

a contrast, I dare assert, as ever two lovers of one

woman presented.

Tip, abashed and afraid, brushed the hair out of his

eyes, and made an unsuccessful attempt to look the handsome

and smiling Cephas in the face.

“Do you pretend you did not hear — with all these

ears?” said the Judge's son.

“I — I was huntin' fur a shoestring,” murmured Tip,

casting dismayed glances along the ground. “I lost one

here som'eres.”

“Tip,” said Cephas, putting his cane under Master Tansley's

chin to assist him in holding up his head, “look me

in the eye, and tell me, — what is the difference 'twixt you

and that corn?”

“I d'n' know — what?” And, liberating his chin, Tip

dropped his head again, and began kicking in the grass in

search of the imaginary shoestring.

“That is lying on the ground, and you are lying — on

your feet,” said Cephas.

Tip replied that he was going to the woods for beanpoles,

and that he took the corn to feed the cattle in the

“back pastur', 'cause they hooked.”

“I wish you were as innocent of hooking as the cattle

are!” said the incredulous Cephas. “Go and put the saddle

on Pericles.”

Tip proceeded in a straight line to the stable, his pockets

dropping corn by the way; while Cephas, laughing

quietly, walked up and down under the trees.

“Hoss 's ready,” muttered Tip, from the barn door.

Instead of leading Pericles out, he left him in the stall,

and climbed up into the hayloft to hide, and brood over

his misfortune until his rival's departure. It was not alone

the affair of the stolen corn that troubled Tip; but from

the fact that Pericles was ordered, he suspected that Cephas

likewise purposed paying a visit to Nancy Blynn.

Resolved to wait and watch, he lay under the dusty roof,

chewing the bitter cud of envy, and now and then a stem of

new-mown timothy, till Cephas entered the stalls beneath,

and said “Be still!” in his clear, resonant tones, to Pericles.

Pericles uttered a quick, low whinny of recognition, and

ceased pawing the floor.

“Are you there, Cephas?” presently said another voice.

It was that of the Judge, who had followed his son into

the barn. Tip lay with his elbows on the hay, and listened.

“Going to ride, are you? Who saddled this horse?”

“Tip,” replied Cephas.

“He did n't half curry him. Wait a minute. I 'm

ashamed to let a horse go out looking so.”

And the Judge began to polish off Pericles with wisps of

straw.

“Darned ef I care!” muttered Tip.

“Cephas,” said the Judge, “I don't want to make you

vain, but I must say you ride the handsomest colt in the

county. I 'm proud of Pericles. Does his shoe pinch him

lately?”

“Not since 't was set. He looks well enough, father.

Your eyes are better than mine,” said Cephas, “if you can

see any dust on his coat.”

“I luf to rub a colt, — it does 'em so much good,” rejoined

the Judge. “Cephas, if you 're going by 'Squire Stedman's,

I 'd like to have you call and get that mortgage.”

“I don't think I shall ride that way, father. I 'll go for

it in the morning, however.”

“Never mind, unless you happen that way. Just hand

me a wisp of that straw, Cephas.”

Cephas handed his father the straw. The Judge rubbed

away some seconds longer, then said carelessly, “If you

are going up the mountain, I wish you would stop and

tell Colby I 'll take those lambs, and send for 'em next

week.”

“I 'm not sure that I shall go as far as Colby's,” replied

Cephas.

“People say” — the Judge's voice changed slightly —

“you don't often get farther than the Widow Blynn's when

you travel that road. How is it?”

“Ask the widow,” said Cephas.

“Ask her daughter, more like,” rejoined the Judge.

“Cephas, I 've kind o' felt as though I ought to have a

little talk with you about that matter. I hope you a'n't

fooling the girl, Cephas.”

And the Judge, having broached the subject to which

all his rubbing had been introductory and his remarks a

prologue, waited anxiously for his son's reply.

Cephas assured him that he could never be guilty of

fooling any girl, much less one so worthy as Miss Nancy

Blynn.

“I 'm glad to hear it!” exclaimed the Judge. “Of

course I never believed you could do such a thing. But

we should be careful of appearances, Cephas. (Just another

little handful of straw; that will do.) People have

already got up the absurd story that you are going to

marry Nancy.”

Tip's ears tingled. There was a brief silence, broken

only by the rustling of the straw. Then Cephas said,

“Why absurd, father?”

“Absurd — because — why, of course it is n't true, is

it?”

“I must confess, father,” replied Cephas, “the idea has

occurred to me that Nancy — would make me — a good

wife.”

It is impossible to say which was most astonished by

this candid avowal, the Judge or Master William Tansley.

The latter had never once imagined that Cephas's intentions

respecting Nancy were so serious; and now the inevitable

conviction forced upon him, that, if his rich rival really

wished to marry her, there was no possible chance left for

him, smote his heart with qualms of despair.

“Cephas, you stagger me!” said the Judge. “A

young man of your education and prospects —”

“Nancy is not without some education, father,” interposed

Cephas, as the Judge hesitated. “Better than that,

she has heart and soul. She is worthy to be any man's

wife!”

Although Tip entertained precisely the same opinions,

he was greatly dismayed to hear them expressed so generously

by Cephas.

The Judge rubbed away again at Pericles's flanks and

shoulders with wisps of straw.

“No doubt, Cephas, you think so; and I have n't anything

agin Nancy; she 's a good girl enough, fur 's I

know. But just reflect on 't, — you 're of age, and in one

sense you can do as you please, but you a'n't too old to

hear to reason. You know you might marry 'most any

girl you choose.”

“So I thought, and I choose Nancy,” answered Cephas,

preparing to lead out Pericles.

“I wish the hoss 'd fling him, and break his neck!”

whispered the devil in Tip's heart.

“Don't be hasty; wait a minute, Cephas,” said the

Judge. “You know what I mean, — you could marry

rich. Take a practical view of the matter. Get rid of

these boyish notions. Just think how it will look for a

young man of your cloth — worth twenty thousand dollars

any day I 'm a mind to give it to you — to go and marry

the Widow Blynn's daughter, — a girl that takes in sewing!

What are ye thinking of, Cephas?”

“I hear,” replied Cephas, quietly, “she does her sewing

well.”

“Suppose she does? She 'd make a good enough wife

for some such fellow as Tip, no doubt; but I thought a

son of mine would ha' looked higher. Think of you and

Tip after the same girl! Come, if you 've any pride about

you, you 'll pull the saddle off the colt and stay at home.”

Although the Judge's speech, as we perceive, was not

quite free from provincialisms, his arguments were none

the less powerful on that account. He said a good deal

more in the same strain, holding out threats of unforgiveness

and disinheritance on the one hand, and praise and

promises on the other; Cephas standing with the bridle

in his hand, and poor Tip's anxious heart beating like a

pendulum between the hope that his rival would be convinced

and the fear that he would not.

“The question is simply this, father,” said Cephas,

growing impatient: “which to choose, love or money?

And I assure you I 'd much rather please you than displease

you.”

“That 's the way to talk, Cephas! That sounds like!”

exclaimed the Judge.

“But if I choose money,” Cephas hastened to say,

“money it shall be. I ought to make a good thing out

of it. What will you give to make it an object?”

“Give? Give you all I 've got, of course. What 's

mine is yours, — or will be, some day.”

“Some day is n't the thing. I prefer one good bird in

the hand to any number of fine songsters in the bush.

Give me five thousand dollars, and it 's a bargain.”

“Pooh! pooh!” said the Judge.

“Very well; then stand aside and let me and Pericles

pass.”

“Don't be unreasonable, Cephas? Let the colt stand.

What do you want of five thousand dollars?”

“Never mind; if you don't see fit to give it, I 'll go and

see Nancy.”

“No, no, you sha' n't! Let go the bridle! I 'd ruther

give ten thousand.”

“Very well; give me ten, then!”

“I mean — don't go to being wild and headstrong now!

you.”

“I 'll divide the difference with you,” said Cephas.

“You shall give me three thousand, and that, you must

confess, is very little.”

“It 's a bargain!” exclaimed the Judge. And Tip was

thrilled with joy.

“I 'm sorry I did n't stick to five thousand!” said

Cephe. “But I wish to ask, can I, for instance, marry

Melissa More? Next to Nancy, she is the prettiest girl in

town.”

“But she has no position; there is the same objection

to her there is to Nancy. The bargain is, you are not to

marry any poor girl; and I mean to have it in writing.

So pull off the saddle and come into the house.”

“If I had been shrewd I might just as well have got

five thousand,” said Cephas.

Tip Tansley, more excited than he had ever been in his

life, waited until the two had left the barn; then, creeping

over the hay, hitting his head in the dark against the

low rafters, he slid down from his hiding-place, carefully

descended the stairs, gathered up what he could find of

the scattered ears of tucket, and set out to run through the

orchard and across the fields to the Widow Blynn's cottage.

The evening was starry, and the edges of the few dark

clouds that lay low in the east predicted the rising moon.

Halting only to climb fences, or to pick up now and then

the corn that persisted in dropping from his pockets, or to

scrutinize some object that he thought looked “pokerish”

in the dark, prudently shunning the dismal woods on one

side, and the pasture where the “hooking” cattle were on

the other, Tip kept on, and arrived, all palpitating and

perspiring, at the widow's house, just as the big red moon

was coming up amidst the clouds over the hill. He had

in his flight; for Tip, ardently as he loved the beautiful

Nancy, could lay no claim to her on the poetical ground

that “the brave deserve the fair.”

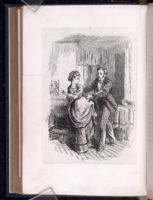

With uncertain knuckles Tip rapped on the humble

door, having first looked through the kitchen window, and

seen the widow sitting within, sewing by the light of a

tallow candle.

“Good evening, William,” said Mrs. Blynn, opening the

door, with her spectacles on her forehead, and her work

gathered up in her lap under her bent figure. “Come in;

take a chair.”

“Guess I can't stop,” replied Tip, sidling into the room

with his hat on. “How 's all the folks? Nancy to

hum?”

“Nancy's up stairs; I 'll speak to her. — Nancy,” called

the widow at the chamber door, “Tip is here! — Better

take a chair while you stop,” she added, smiling upon the

visitor, who always, on arriving, “guessed he could n't

stop,” and usually ended by remaining until he was sent

away.

“Wal, may as well; jest as cheap settin' as standin',”

said Tip, depositing the burden of his personality — weight,

146 lbs. — upon one of the creaky, splint-bottomed chairs.

“Pooty warm night, kind o',” raising his arm to wipe his

face with his sleeve; upon which an ear of that discontented

tucket took occasion to tumble upon the floor.

“Hello! what 's that? By gracious, if 't a'n't green corn!

Got any fire? Guess we 'll have a roast.”

And Tip, taking off his hat, began to empty his stuffed

pockets into it.

“Law me!” said the widow, squinting over her work.

“I thought your pockets stuck out amazin'! I ha'n't

had the first taste of green corn this year. It 's real kind

can't think of roastin' on 't to-night, as I see.”

“Mebby Nancy will,” chuckled Tip. “A'n't she comin'

down? — Any time to-night, Nancy!” cried Tip, raising

his voice, to be heard by his beloved in her retreat.

“You do'no' what I brought ye!”

Now, sad as the truth may sound to the reader sympathizing

with Tip, Nancy cared little what he had brought,

and experienced no very ardent desire to come down and

meet him. She sat at her window, looking at the stars,

and thinking of somebody who she had hoped would visit

her that night. But that somebody was not Tip; and

although the first sound of his footsteps had set her heart

fluttering with expectation, his near approach, breathing

fast and loud, had given her a chill of disappointment,

almost of disgust, and she now much preferred her own

thoughts, and the moonrise through the trees in the direction

of Judge Boxton's house, to all the green corn and all

the green lovers in New England. Her mother, however,

who commiserated Tip, and believed as much in being

civil to neighbors as she did in keeping the Sabbath, called

again, and gave her no peace until she had left the window,

the moonrise, and her romantic dreams, and descended

into the prosaic atmosphere of the kitchen, and

of Tip and his corn.

How lovely she looked, to Tip's eyes! Her plain, neat

calico gown, enfolding a wonderful little rounded embodiment

of grace and beauty, seemed to him an attire fit

for any queen or fairy that ever lived. But it was the

same old tragic story over again, — although Tip loved

Nancy, Nancy loved not Tip. However he might flatter

himself, her regard for him was on the cool side of sisterly,

— simply the toleration of a kindly heart for one who was

not to blame for being less bright than other people.

She took her sewing, and sat by the table, O, so beautiful!

Tip thought, and enveloped in a charmed atmosphere

which seemed to touch and transfigure every object

except himself. The humble apartment, the splint-bottomed

chairs, the stockings drying on the pole, even the

widow's cap and gown, and the old black snuffers on the

table, — all, save poor, homely Tip, stole a ray of grace

from the halo of her loveliness.

Nancy discouraged the proposition of roasting corn, and

otherwise deeply grieved her visitor by intently working

and thinking, instead of taking part in the conversation.

At length a bright idea occurred to him.

“Got a slate and pencil?”

The widow furnished the required articles. He then

found a book, and, using the cover as a rule, marked out

the plan of a game.

“Fox and geese, Nancy; ye play?” And having

picked off a sufficient number of kernels from one of the

ears of corn, and placed them upon the slate for geese, he

selected the largest he could find for a fox, stuck it upon a

pin, and proceeded to roast it in the candle.

“Which 'll ye have, Nancy?” — pushing the slate

toward her; “take your choice, and give me the geese;

then beat me if you can! Come, won't ye play?”

“O dear, Tip, what a tease you are!” said Nancy. “I

don't want to play. I must work. Get mother to play

with you, Tip.”

“She don't wanter!” exclaimed Tip. “Come, Nancy;

then I 'll tell ye suthin' I heard jest 'fore I come away, —

suthin' 'bout you!”

And Tip, assuming a careless air, proceeded to pile up

the ears of corn, log-house fashion, upon the table, while

Nancy was finishing her seam.

“About me?” she echoed.

“You 'd ha' thought so!” said Tip, slyly glancing over

the corn as he spoke, to watch the effect on Nancy.

“Cephe and the old man had the all-firedest row, — tell

you!”

He hitched around in his chair, and resting his elbows

on his knees, looked up, shrewd and grinning, into her

face.

“William Tansley, what do you mean?”

“As if you could n't guess! Cephe was comin' to see

you to-night; but he won't,” chuckled Tip. “Say! ye

ready for fox and geese?”

“How do you know that?” demanded Nancy.

“'Cause I heard! The old man stopped him, and

Cephe was goin' to ride over him, but the old man was

too much for him; he jerked him off the hoss, and there

they had it, lickety-switch, rough-and-tumble, till Cephe

give in, and told the old man, ruther 'n have any words,

he 'd promise never to come and see you agin if he 'd give

him three thousand dollars; and the old man said 't was a

bargain!”

“Is that true, Tip?” cried the widow, dropping her

work and raising her hands.

“True as I live and breathe, and draw the breath of life,

and have a livin' bein'!” Tip solemnly affirmed.

“Just as I always told you, Nancy!” exclaimed the

widow. “I knew how it would be. I felt sartin Cephas

could n't be depended upon. His father never 'd hear a

word to it, I always said. Now don't feel bad, Nancy;

don't mind it. It 'll be all for the best, I hope. Now

don't, Nancy; don't, I beg and beseech.”

She saw plainly by the convulsive movement of the

girl's bosom and the quivering of her lip that some passionate

demonstration was threatened. Tip meanwhile

had advanced his chair still nearer, contorting his neck

nose almost touched her cheek.

“What do ye think now of Cephe Boxton?” he asked,

tauntingly; “hey?”

A stinging blow upon the ear rewarded his impertinence,

and he recoiled so suddenly that his chair went

over and threw him sprawling upon the floor.

“Gosh all hemlock!” he muttered, scrambling to his

feet, rubbing first his elbow, then his ear. “What 's that

fur, I 'd like to know, — knockin' a feller down?”

“What do I think of Cephas Boxton?” cried Nancy.

“I think the same I did before, — why should n't I?

Your slander is no slander, Now sit down and behave

yourself, and don't put your face too near mine, if you

don't want your ears boxed!”

“Why, Nancy, how could you?” groaned the widow.

Nancy made no reply, but resumed her work very much

as if nothing had happened.

“Hurt you much, William?”

“Not much; only it made my elbow sing like all

Jerewsalem! Never mind; she 'll find out! Where 's my

hat?”

“You a'n't going, be ye?” said Mrs. Blynn, with an air

of solicitude.

“I guess I a'n't wanted here,” mumbled Tip, pulling his

hat over his ears. He struck the slate, scattering the fox

and geese, and demolished the house of green corn. “You

can keep that; I don't want it. Good night, Miss Blynn.”

Tip placed peculiar emphasis upon the name, and fumbled

a good while with the latch, expecting Nancy would

say something; but she maintained a cool and dignified

silence, and as nobody urged him to stay, he reluctantly

departed, his heart full of injury, and his hopes collapsed

like his pockets.

For some minutes Nancy continued to sew intently and

fast, her flushed face bowed over the seam; then suddenly

her eyes blurred, her fingers forgot their cunning, the

needle shot blindly hither and thither, and the quickly

drawn thread snapped in twain.

“Nancy! Nancy! don't!” pleaded Mrs. Blynn; “I

beg of ye, now don't!”

“O mother,” burst forth the young girl, with sobs, “I

am so unhappy! What did I strike poor Tip for? He

did not know any better. I am always doing something

so wrong! He could not have made up the story.

Cephas would have come here to-night, — I know he

would!”

“Poor child! poor child!” said Mrs. Blynn. “Why

could n't you hear to me? I always told you to be careful

and not like Cephas too well. But maybe Tip did n't

understand. Maybe Cephas will come to-morrow, and

then all will be explained.”

“Cephas is true, I know, I know!” wept Nancy, “but

his father —”

The morrow came and passed, and no Cephas. The

next day was Sunday, and Nancy went to church, not

with an undivided heart, but with human love and hope

and grief mingling strangely with her prayers. She knew

Cephas would be there, and felt that a glance of his eye

would tell her all. But — for the first time in many

months it happened — they sat in the same house of worship,

she with her mother in their humble corner, he in

the Judge's conspicuous pew, and no word or look passed

between them. She went home, still to wait. Day after

day of leaden loneliness, night after night of watching and

despair, and still no Cephas. Tip also had discontinued

his visits. Mrs. Blynn saw a slow, certain change come

over her child; her joyous laugh rang no more, neither

seemed disciplining herself to bear with patience and

serenity the desolateness of her lot.

One evening it was stormy, and Nancy and her mother

were together in the plain, tidy kitchen, both sewing and

both silent; gusts and rain lashing the windows, and the

cat purring in a chair. Nancy's heart was more quiet

than usual; for, although expectation was not quite

extinct, no visitor surely could be looked for on such a

night. Suddenly, however, amidst the sounds of the

storm, she heard footsteps and a knock at the door. Yet

she need not have started and changed color so tumultuously,

for the visitor was only Tip.

“Good evenin',” said young Master Tansley, stamping,

pulling off his dripping hat, and shaking it. “I 'd no idee

it rained so! I was goin' by, and thought I 'd stop in.

Ye mad, Nancy?” And he peered at the young girl from

beneath his wet hair with a bashful grin.

Nancy's heart was too much softened to cherish any

resentment, and with suffused eyes she begged Tip to

forgive the blow.

“Wal! I do'no' what I 'd done to be knocked down

fur,” began Tip, with a pouting and aggrieved air;

“though I s'pose I dew, tew. But I guess what I told ye

turned out about so, after all; did n't it, hey?”

At Nancy's look of distress, Mrs. Blynn made signs for

Tip to forbear. But he had come too far through the

darkness and rain with an exciting piece of news to be

thus easily silenced.

“I ha'n't brought ye no corn this time, for I did n't

know as you 'd roast it if I did. Say, Nancy! Cephe and

the old man had it agin to-day; and the Judge forked

over the three thousand dollars; I seen him! He was

only waitin' to raise it. It 's real mean in Cephe, I s'pose

dollars is a 'tarnal slue of money!”

Hugely satisfied with the effect this announcement produced,

Tip sprawled upon a chair and chewed a stick, like

one resolved to make himself comfortable for the evening.

“Saxafrax, — ye want some?” he said, breaking off with

his teeth a liberal piece of the stick. “Say, Nancy! ye

need n't look so mad. Cephe has sold out, I tell ye; and

when I offer ye saxafrax, ye may as well take some.”

Not without effort Nancy held her peace; and Tip,

extending the fragment of the sassafras-root which his

teeth had split off, was complacently urging her to accept

it, — “'T was real good,” — when the sound of hoofs was

heard; a halt at the gate; a horseman dismounting, leading

his animal to the shed; a voice saying “Be still,

Pericles!” and footsteps approaching the door.

“Nancy! Nancy!” articulated Mrs. Blynn, scarcely

less agitated than her daughter, “he has come!”

“It 's Cephe!” whispered Tip, hoarsely. “If he should

ketch me here! I — I guess I 'll go! Confound that

Cephe, anyhow!”

Rap, rap! two light, decisive strokes of a riding-whip

on the kitchen door.

Mrs. Blynn glanced around to see if everything was tidy;

and Tip, dropping his sassafras, whirled about and wheeled

about like Jim Crow in the excitement of the moment.

“Mother, go!” uttered Nancy, pale with emotion, hurriedly

pointing to the door.

She made her escape by the stairway; observing which,

the bewildered Tip, who had indulged a frantic thought of

leaping from the window to avoid meeting his dread rival,

changed his mind and rushed after her. Unadvised of his

intention, and thinking only of shutting herself from the

sight of young Boxton, Nancy closed the kitchen door

him insensible to pain, and he followed her, scrambling up

the dark staircase just as Mrs. Blynn admitted Cephas.

Nancy did not immediately perceive what had occurred;

but presently, amidst the sounds of the rain on the roof

and of the wind about the gables, she heard the unmistakable

perturbed breathing of her luckless lover.

“Nancy,” whispered Tip, “where be ye? I 've most

broke my head agin this blasted beam!”

“What are you here for?” demanded Nancy.

“'Cause I did n't want him to see me. He won't stop

but a minute; then I 'll go down. I did give my head

the all-firedest tunk!” said Tip.

Mrs. Blynn opened the door to inform Nancy of the arrival

of her visitor, and the light from below, partially illuminating

the fugitive's retreat, showed Tip in a sitting posture

on one of the upper stairs, diligently rubbing that portion

of his cranium which had come in collision with the beam.

“Say, Nancy, don't go!” whispered Tip; “don't leave

me here in the dark!”

Nancy had too many tumultuous thoughts of her own

to give much heed to his distress; and having hastily

arranged her hair and dress by the sense of touch, she

glided by him, bidding him keep quiet, and descended the

stairs to the door, which she closed after her, leaving him

to the wretched solitude of the place, which appeared to

him a hundred fold more dark and dreadful than before.

Cephas in the mean time had divested himself of his oil-cloth

capote, and entered the neat little sitting-room, to

which he was civilly shown by the widow. “Nancy 'll

be down in a minute.” And placing a candle upon the

mantel-piece, Mrs. Blynn withdrew.

Nancy, having regained her self-possession, appeared

mighty dignified before her lover; gave him a passive

seated herself at a cool and respectable distance.

“Nancy, what is the matter?” said Cephas, in mingled

amazement and alarm. “You act as though I was a

pedler, and you did n't care to trade.”

“You can trade, sir; you can make what bargains you

please with others; but —” Nancy's aching and swelling

heart came up and choked her.

“Nancy! what have I done? What has changed you

so? Have you forgotten — the last time I was here?”

“'T would not be strange if I had, it was so long ago!”

Poor Nancy spoke cuttingly; but her sarcasm was as a

sword with two points, which pierced her own heart quite

as much as it wounded her lover's.

“Nancy,” said Cephas, and he took her hand again so

tenderly that it was like putting heaven away to withdraw

it, “could n't you trust me? Has n't your heart assured

you that I could never stay away from you so without

good reasons?”

“O, I don't doubt but you had reasons!” replied

Nancy, with a bursting anguish in her tones. “But such

reasons!”

“Such reasons?” repeated Cephas, grieved and repelled.

“Will you please inform me what you mean? For, as I

live, I am ignorant!”

“Ah, Cephas! it is not true, then,” cried Nancy, with

sudden hope, “that — your father —”

“What of my father?”

“That he has offered you money —”

A vivid emotion flashed across the young man's face.

“I would have preferred to tell you without being

questioned so sharply,” he replied. “But since hearsay

has got the start of me, and brought you the news, I can

only answer — he has offered me money.”

“To buy you — to hire you —”

“Not to marry any poor girl, — that 's the bargain,

Nancy,” said Cephas, with the tenderest of smiles.

“And you have accepted?” cried Nancy, quickly.

“I have accepted,” responded Cephas.

Nancy uttered not a word.

“I came to tell you all this; but I should have told

you in a different way, could I have had my choice,” said

Cephas. “What I have done is for your happiness as

much as my own. My father threatened to disinherit me

if I married a poor girl; and how could I bear the thought

of subjecting you to such a lot? He has given me three

thousand dollars; I only received it to-day, or I should

have come to you before, for, Nancy, — do not look so

strange! — it is for you, this money, — do you hear?”

He attempted to draw her toward him, but she sprang

indignantly to her feet.

“Cephas! You offer me money!”

“Nancy!” — Cephas caught her and folded her in his

arms, — “don't you understand? It is your dowry! You

are no longer a poor girl. I promised not to marry any

poor girl, but I never promised not to marry you. Accept

the dowry; then you will be a rich girl, and — my wife,

my wife, Nancy!”

“O Cephas! is it true? Let me look at you!” She

held him firm, and looked into his face, and into his deep

tender eyes. “It is true!”

What more was said or done I am unable to relate; for

about this time there came from another part of the house

a dull, reverberating sound, succeeded by a rapid series of

concussions, as of some ponderous body descending in a

swift but irregular manner from the top to the bottom of

the stairs. It was Master William Tansley, who, groping

about in the dark with intent to find a stove-pipe hole at

and tumbled from landing to landing, in obedience to the

dangerous laws of gravitation. Mrs. Blynn flew to open

the door; found him helplessly kicking on his back, with

his head in the rag-bag; drew him forth by one arm;

ascertained that he had met with no injuries which a little

salve would not heal; patched him up almost as good as

new; gave him her sympathy and a lantern to go home

with, and kindly bade him good night.

So ended. Tip Tansley's unfortunate love-affair; and I

am pleased to relate that his broken heart recovered from

its hurts almost as speedily as his broken head.

A month later the village clergyman was called to

administer the vows of wedlock to a pair of happy lovers

in the Widow Blynn's cottage; and the next morning there

went abroad the report of a marriage which surprised the

good people of the parish generally, and Judge Boxton

more particularly.

In the afternoon of that day Cephas rode home to pay

his respects to the old gentleman, and ask him if he would

like an introduction to the bride.

“Cephas!” cried the Judge, filled with wrath, smiting

his son's written agreement with his angry hand, “look

here! your promise! Have you forgotten?”

“Read it, please,” said Cephas.

“In consideration,” began the Judge, running his troubled

eye over the paper, “.... I do hereby pledge myself,

never, at any time, or in any place, to marry any

poor girl.”

“You will find,” said Cephas, “that I have acted

according to the strict terms of our agreement. And I

have the honor to inform you, sir, that I have married a

person who, with other attractions, possesses the handsome

trifle of three thousand dollars.”

The Judge fumed, made use of an oath or two, and

talked loudly of disinheritance and cutting off with a

shilling.

“I should be very sorry to have you do such a thing,”

rejoined Cephas, respectfully; “but, after all, it is n't as

though I had not received a neat little fortune by the way

of my wife.”

A retort so happy that the Judge ended with a hearty

acknowledgment of his son's superior wit, and an invitation

to come home and lodge his lovely encumbrance

beneath the parental roof.

Thereupon Cephas took a roll of notes from his pocket.

“All jesting aside,” said he, “I must first square a little

matter of business with which my wife has commissioned

me. She is more scrupulous than the son of my father,

and she refused to receive the money until I had promised

to return it to you as soon as we should be married. And

here it is!”

“Fie, fie!” cried the Judge. “Keep the money.

She 's a noble girl, after all, — too good for a rogue like

you!”

“I know it!” said Cephas, humbly, with tears in his

eyes; for recollections of a somewhat wild and wayward

youth, mingling with the conscious possession of so much

love and happiness, melted his heart with unspeakable

contrition and gratitude.

| Coupon bonds, and other stories | ||