| VIII.

UNCLE JIM'S EVENING CALL. Coupon bonds, and other stories | ||

8. VIII.

UNCLE JIM'S EVENING CALL.

Again that Sunday evening old man Dracutt and his

wife sat together by their lonely kitchen fire, but with no

Clinton now to come in and break the awful silence and

monotony of their lives. The lamp had not been lighted;

only the moonlight lay upon the floor, and the still whiteness

of the winter's night filled the room with its pallid

reflection.

The old man sat in his chair erect, but looking more

crushed together in the neck and jaws than ever, while his

wife appeared bent by an added load of trouble. There

was utter silence, except that now and then a soft, low sob

was heard; the old lady was thinking of that night two

weeks ago, and weeping. Then, ever and anon, from without

came a deep, muffled, reverberating roar or groan, as

if Nature herself sympathized with their woe. If it had

been summer, you would have said it thundered. But it

was the pond complaining, the thick-ribbed ice shuddering

and moaning under the cold, starry night. Every sudden,

prolonged peal reached the ears of the lonely old

couple in the bereaved house, reminding them of their

loss.

They had not spoken to each other yet, nor had there

been much need that they should speak, so well had they

learned in all those years to understand each other without

words. But they had shown in many ways that they

felt more kindly toward each other since this great affliction

came upon them. And now, old lady Dracutt sitting

there, weeping, in the gloom, longed to speak once more

to her husband, and to hear his voice.

She was ready to say, “Forgive me, Jonathan,” but was

afraid to utter the words. How strangely they would sound,

breaking the unnatural silence that had kept them dumb to

each other for twelve years! Again and again she tried

to speak, but could not bring her tongue to shape the

syllables; it seemed paralyzed; she began to feel a strange,

benumbing fear that she would never have power to break

that silence, that it had been taken from her as a punishment

for her long sin of wilfulness and hard-heartedness

toward him.

While she was thus struggling ineffectually with herself,

suddenly another voice broke the spell which she could

not, — to her terror and joy, her husband's voice.

“I have been thinking, Jane —” said he, and stopped.

“O Jonathan! you have spoken!” she cried out, with

a wild sob. “God bless you, God bless you, Jonathan!”

“Jane, I thought I had better speak,” said the old man

in a trembling voice. “I have been wantin' to for many

days. I think I have been wrong, Jane.”

“Don't say it, don't say it, Jonathan,” said the old lady,

sinking to the floor, and throwing her clasped hands across

his knees. “I should have asked your forgiveness. I have

tried to. I was trying to now, when you spoke. O Jonathan,

Jonathan!”

“God forgive us! I think we have both been wrong, but

I have been most in the wrong,” said the old man. Then

a long silence followed, broken by sighs and sobs, and the

moaning peals of the pond.

“I 've been thinkin',” resumed the old man, — she was

at last seated by his side once more, and her hand was in

his, — “that I can't, somehow, bear to have Clinton's memory

passed over in this way. I think we ought to have

funeral sarvices for him, even without —”

“Yes,” said she, “I have felt so, too. It will be some

satisfaction. I said as much to Cousin James.”

“He told me you did. He told me, too, what you said

about my blaming myself so much on account of the boy.

And it touched me, it touched me; I did n't desarve that

you should feel and speak so kindly.”

“But, Jonathan,” replied Jane, wiping her eyes, “you

said nothin' to him that night that it was n't your duty to

say. I felt that, though I hated to have him hurt.”

“I don't know, I don't know. If I had been different,

he might have been different. No wonder he was cross

sometimes. It 's the hardest thing for me to reconcile myself

to the fact that my last word to him was unkind.

He would n't have gone off on the pond so the next mornin'

without speakin' to us, if it had n't been for that. I thought

't was my duty to reprimand him, and maybe it was. But

my first duty was to set him an example of cheerfulness

and good temper. What could we expect of him as long

as we two were at enmity?” And the old man ended with

a groan.

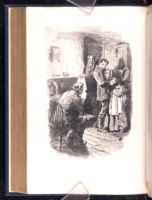

While they were talking, there came a rap at the door.

The old man said, “Walk in,” while the old lady made

haste to light a lamp.

“It 's nobody but me; don't light up for me,” said a

familiar voice, as the tall form of a hale old man appeared

in the doorway.

“Cousin James!” said the old lady, still opening the

wick with the lighted match.

“At this time o' night, and with a knock!” said old

man Dracutt, pushing a chair toward the visitor.

“I knocked because I — I rather thought ye had company,”

said James, glancing his eye about the room as he

sat down.

“You heard talkin', I s'pose,” said old man Dracutt.

and me.”

“Praise the Lord!” exclaimed Uncle Jim (for we like

best the name the young folks called him by). “Bless ye,

Jonathan; bless ye, Jane. I hoped this sorrow would bring

you closer together, and I see it has.”

“It has, it has!” said Jane.

“God's ways are not our ways,” said Uncle Jim, with

deep emotion. “He has done it. He meant it all for your

good.”

“I believe so,” replied Jane. “We have had comfort in

each other to-night, such as we have n't had for twenty

year. But, O James! at what a cost! I 've been thinkin'

the sunshine could n't melt us, and so God sent his lightnin'.

If we had n't been so hard-hearted, then our boy

might have been spared to us.”

“But you will soon become reconciled to his loss,” said

Unlce Jim, philosophically — so very philosophically, indeed,

that old man Dracutt looked at him with reproachful

surprise.

“That can never be, James. There 's only one thing now

that can be any satisfaction to us. This week the ice will

be cut over all that part of the pond. He may be found,

froze into it. If not, then we must have funeral sarvices,

jest the same as if he was. What ails ye, James? Ye

don't listen to me. I thought ye approved of the idee of a

funeral.”

“So I do — that is, so I should — hem!” coughed Uncle

Jim, using his handkerchief, fidgeting in his chair, and

behaving strangely in other ways. “But I would n't hurry

about it. There 's no knowin', ye know — he may be found

yet — and — hem! — the fact is, there 's no sartinty — no

positive sartinty — that he 's drownded, ye know, Jonathan.”

“I wish I did know it,” said Jonathan, somewhat

startled. “If I could think there was a particle of hope!

James,” he went on, with increasing agitation, “what have

you come here for this time o' the evenin'? You don't act

your nat'ral self. There 's somethin' —”

“Yes, there is somethin',” Uncle Jim replied, “and I

want you to be prepared for 't.”

“For Heaven's sake, James!” said the old lady, “what is

it? Have they found the poor boy's body?”

“Not — not exactly that. I tell ye,” Uncle Jim cleared

his throat again, “there 's no positive sartinty about his

bein' drownded. The men said he was on the ice jest a few

seconds before it broke up; but, don't you see, men can't

have much recollection with regard to time, after such an

accident? What seemed to them a few seconds, when they

thought on 't afterwards, might have been a few minutes;

in fact, might have been five, ten minutes. Have ye

thought of that?”

“Yes, yes. But all the sarcumstances, James, — they

are agin the supposition. Where could the poor boy be,

if not there? He could n't have gone off. He had no

money about him. Then, agin, the hammers, James!”

“The hammers! — hem! — yes, Jonathan,” said Uncle

Jim, in the awkwardest manner, and with the strangest

blending of cheerfulness and anxiety in his kind old face,

“about the hammers. Something has come to light with

regard to them; and that 's one thing I 've come to tell you.

Whatever has become of Clinton, they have n't gone to the

bottom of the pond, that 's a sartin case.”

“How do you know?” cried old man Dracutt, almost

fiercely.

“I was told so, on good authority, this very evenin'. I

know jest where them hammers are. They are lyin' in a

corner of the fence, a few rods beyond the tool-house.

from bein' discovered before.”

“Clinton! Clinton! then he may be alive!” broke

forth the old lady, with sudden and wild hope.

“It is more than probable. In fact, a — person — has

been heard from, up in New Hampshire, who answers his

description. A young man come to town this evenin' and

brought the news. He 'll be here in a few minutes. Be

calm, Jane, I — I believe he is comin' now!” (Footsteps in

the creaking snow outside.) “So, do be composed, Jonathan!

You know now who it is!” as the door opened.

“Clinton!” shrieked the old lady, tottering forward,

and falling on the new-comer's neck, with hysterical sobs.

It was Clinton, sure enough, and Phil Kermer with him.

| VIII.

UNCLE JIM'S EVENING CALL. Coupon bonds, and other stories | ||