| | ||

A Fielding Discovery, with Some Remarks on the

Canon

by

M. C. with R. R.

Battestin

In June 1739, in order to secure evidence for an action of libel, agents of the Walpole ministry raided the offices of the printer and editor of the Opposition organ, Common Sense, and seized their papers. Of these, 218 autograph items, the great majority representing copy for the printer, are preserved together at the Public Record Office (Chancery Lane)—call number: SP9/35. Since this collection by no means comprises a complete run of the printer's copy to the time of seizure, and since—no doubt for prudential reasons—none of the copy is signed, scholars will find this material of limited use in identifying contributors, though, by a comparative analysis of the handwriting, it is a simple matter to distinguish, in a general way, articles written by the editor from those submitted by occasional correspondents to the journal.

Included among these papers, however, is at least one item of exceptional interest; for here, in the form of a pseudonymous letter to the editor recommending silence as "the utmost Perfection of human Wisdom," is the only extant literary prose manuscript by Henry Fielding. Signed "Mum Budget" and dated from Devon on April Fool's Day 1738, this witty piece, though published in Common Sense on 13 May, has never been attributed to Fielding. It is valuable, however, not only as an important addition to the canon, representing one of Fielding's earliest known publications as a periodical essayist, the form in which—as editor of The Champion (1739-41), The True Patriot (1745-46), The Jacobite's Journal (1747-48), and The Covent-Garden Journal (1752)—he would soon outshine every rival for a decade. What is more, appearing in the midst of the two-and-a-half-year interval between the passage of the Theatrical Licensing Act (June 1737), which put an end to his career as a dramatist, and the publication of The Champion (November 1739), when he emerged as principal journalist for the Opposition, the essay sheds light on Fielding's personal circumstances and political relationships in one of the most obscure periods of his life. Because

Sponsored by his friends in Opposition, Common Sense: or, The Englishman's Journal began publication on 5 February 1737, during Fielding's final season as manager of the Little Theatre in the Haymarket. In a month's time, with the production of The Historical Register, he would cap the brilliant success of Pasquin a year earlier—a triumph no less spectacular than it was disastrous in its consequences for his career as a playwright; for, though Fielding's satire in these plays spared neither party, it linked him in the public mind with the Opposition's cause and moved the Ministry to silence him. As one ministerial writer was well assured, Fielding's success with Pasquin had caused him to be "secretly buoy'd up, by some of the greatest Wits and finest Gentlemen of the Age"[2] —among them, surely, Lyttelton and Chesterfield, who had now initiated the new journal. Its editor and principal writer, however, was the Irishman, Charles Molloy (d. 1767), himself a comic dramatist manqué and, as the former author of Fog's Weekly Journal (1728-37), a journalist well skilled in the art of making ministerial politicians die sweetly in print. Its printer was the inflexible Tory, John Purser.

In a sense Fielding, too, was associated with this paper from the start; for its title had been borrowed from the "emblematical" figure whose "Tragedy" is rehearsed, to hilarious effect, in the final acts of Pasquin. Though in Pasquin Common Sense suffered what might seem her inevitable fate in the age of Walpole, in the pages of Molloy's weekly paper, presumably, she would live on, with due acknowledgments to Fielding, who understood her best: "An ingenious Dramatick Author," we are reminded in the first issue, "has consider'd Common Sense as so extraordinary a Thing, that he has lately, with great Wit and Humour, not only personified it, but dignified it too with the Title of a Queen . . . ." A few months later, when Fielding needed a "Vehicle" by which to answer a ministerial attack against the alleged licentiousness of his political satire in The Historical Register, it was, predictably, Molloy

We may take it as certain, I believe, that after the "Pasquin" letter almost precisely a year went by before Fielding made his next appearance in Common Sense, this time as that wonderfully garrulous advocate of the wisdom of holding one's tongue, "Mum Budget." The essay begins, accordingly, with his anticipating the editor's surprise "at not

The discovery of this manuscript, of course, makes the possibility all the more attractive that Fielding made other contributions to Common Sense during the eighteen months that would pass before he launched his own paper in behalf of the Opposition. Textually, the relationship between the manuscript and the two printed versions of the essay—that of the original issue of Common Sense (13 May 1738) and that appearing in the two-volume reprint (1738-39)—reveals, however, certain peculiarities which complicate the problem of identifying Fielding's hand elsewhere in the journal. Most significant of these is the fact that, in setting the article, the compositor systematically, and without editorial authority, altered a characteristic of Fielding's style which has long served as an indispensable test for anyone proposing additions to the canon: in every instance Fielding's favorite archaism, the use of hath for has, has been modernized. And presumably his doth's would have been similarly treated if he had had occasion to use that verb in the essay. To compound the problem, it is clear that this particular sophistication was not a feature of Purser's "house style": the printed versions of the "Pasquin" letter retain Fielding's characteristic usage. Indeed, Molloy himself often (though not invariably) prefers the same archaisms. These changes from the manuscript, therefore, would seem to be an expression of the stylistic taste of a particular compositor—who, since he was no doubt employed at other times by Purser, may be supposed to have treated other essays in the same manner. What this practice means to anyone looking for signs of Fielding's authorship in the published numbers of Common Sense is obvious: we cannot now automatically exclude an essay from consideration merely because it shows has and does where Fielding would have used hath and doth.

Inspection of the manuscript, and collation of the manuscript with

For these reasons, then, the task of identifying Fielding's hand in the published numbers of Common Sense cannot be undertaken very confidently. Without the hath-doth test to rely on, we have lost one simple means of narrowing the range of possibilities. The manuscripts preserved at the Public Record Office are, of course, a considerable help toward this end, and in some instances may serve to chasten the rash: if, for example, we set aside the hath-doth test, the leader published in the journal on 30 September 1738—an ironic allegory of corruption in English society written in the form of a "Letter from Common Honesty to Common Sense"—sounds rather like Fielding; but, as the manuscript proves, he was not the author.[10] And what about the issue of 23 December 1738, in which the author anticipates the satiric analogy between Walpole and Jonathan Wild which Fielding would develop at length in his novel? If, like W. R. Irwin,[11] we had resisted the temptation to attribute

Since all the extant manuscripts of the journal antedate 27-28 June 1739, when Walpole's agents confiscated them,[13] they offer no clues to the authorship of any essays published after that time. In my opinion, however, Fielding did make at least one, and quite possibly two, further contributions to Common Sense during the period before The Champion began publication on 15 November. On 15 September Molloy devoted his front page to two witty and learned letters from, ostensibly,

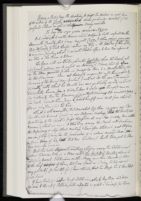

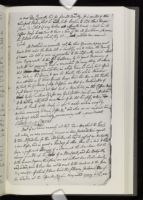

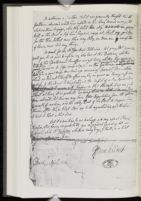

What follows is an annotated transcript of the manuscript in the Public Record Office (Chancery Lane)—call number: SP9/35, items 215-16. The manuscript itself, comprising two folio sheets (12½ by 7¾ inches) with writing on both sides, is photographically reproduced in the plates accompanying this article. In preparing the transcript, I have tried to convey a sense of Fielding's original intentions. Whenever I was confident that I could distinguish these from the changes introduced by Molloy as he edited the copy, I have disregarded the latter in order to restore Fielding's own phrasing and his own practice with respect to the accidentals, particularly paragraphing. Unfortunately, though it is comparatively easy to distinguish between author and editor in substantive matters—Molloy's hand being quite different from Fielding's— it is virtually impossible to do so in the case of pointing. Elsewhere, in

* * *

I believe you may have wondered at not hearing from me in so long time, and will, perhaps, be more surprized at the Reason I am going to give you.—In short, Sir, I am at length thoroughly convinced, that the utmost Perfection of human Wisdom is Silence;[1] and that when a Man hath learnt to hold his Tongue, he may be properly said to have arrived at the highest Pitch of Philosophy.

I am so very fond of this virtue, that I shall do a kind of violence to it (for Silence implies holding the Pen as well as the Tongue) to trumpet forth its Praises, seeing that, upon much deep Reflection, I am persuaded, if any Virtue hath had that universal Assent Wch Mr Lock seems to deny,[2] it must be allowed to be this.

Solomon, the wisest of Men, declares loudly in Commendation of this virtue. In the multitude of Words, says he, there wanteth not Sin: but he that refraineth his Lips is wise. again,—he that hath Knowledge spareth his words. and[3] again, Even a Fool, when he holdeth his Lips, is counted wise; and he that shutteth his Lips is esteemed a Man of Understanding.[4] and in several other Places throughout his Proverbs.

King David is so fond of Silence, that he applauds himself for abstaining even from good words; which, tho' it seems it was extremely troublesome to him, yet he was so resolute in his Perseverance in this virtue, that rather than

The Stoicks, the greatest, wisest and most virtuous of all the Sects of Heathen Philosophers,[6] had this virtue in such Estimation, that it is well known what a long Silence was necessary to qualify a Graduate in their Schools:[7] —whether these great Men imagined, as some have insinuated, that Wisdom, like good Ale, ripened and refined it self by being well corked, I will not decide; or whether they might not, with greater Justice observe, that Wisdom, like Air, being stopped in one place would naturally find a vent in another, and so, by keeping the Mouth close shut, infuse itself into the Muscles of the Face, and thereby create what we call a wise Look, a Quality ever held in great Esteem, and of singular good use in all Philosophical Societies.

Homer, a Poet of deep Penetration, to give his Reader a vast Idea of the wisdom of the Greeks, makes particular mention of the profound Silence in which their Army marched.

oὶ δ'αρ ισαν σιγη μενεα πνειονΤες Aχαιοι.[8]

But, indeed, such are the Honours which Antiquity hath conferred on this admirable Quality, that I may say, with Cicero, si velim omnia percurrere Dies deficeret;[9] I shall therefore confine my self, in the Residue of this Letter, to my own Country, which, I can with Pleasure observe to have been inferiour to no other in her Esteem of Silence.

To begin with our Philosophers,—The Spectator, whom the French call Le Socrate moderne,[10] was so perfect an Observer of Silence, that he assures us he seldom proceeded farther in Conversation than to a Monosyllable; that he had often, among Persons not thoroughly acquainted with him, passed by the name of the Dumb Man: to which I need not add the great Ceremony & Difficulty with which his Mouth was once publickly opened, as it is so

2dly, it is well remembered, that somewhat less than 100 years ago Silence had obtained so much Ground in our Religious Meetings, That the secret, silent Breathings of the Spirit diffused themselves all over the Nation, some notable Remains of which we have at this Day among the People called Quakers;—the Profoundness of whose silent Meetings I have often beheld with great Pleasure, nor can I help observing here the Insinuation of a certain reverend Dean, in a serious Essay of his, that true Christianity hath been put to Silence some time ago among us.[12]

But this Virtue blossoms no where so much as among the Politicians.—A certain ludicrous Poet, in a Piece called the Historical Register, wherein he introduced several Politicians on the Stage, gives this Character of Silence to the chief of them;[13] but I am afraid in so doing, he did not act very politickly for himself: for I have observed, that his Muse hath been silent ever since.

I have heard of a Coffee House Politician, who, by long Study and deep Attention to the Art of Politicks, hath contracted as great a Fondness for Silence as ever Don Quixotte had for Knight Errantry. It is reported of this whimsical Person, that he would bribe Persons to hold their Tongue. I have heard, that if any Fellow attempted to make a Noise in the Coffee House he was sure to have a Sum[14] of the old Gentleman, to procure his future Silence; which, they tell me, produced some comical Events.

As Mankind are generally apt, in their Opinions, to pay great Regard to the value the Person sets on himself, and to esteem the Beauty of Women and Wit of men in proportion to the Difficulty which attends their Enjoyment:

But if we search narrowly into these Characters, which the French call outrez, we may commonly discover in them Contradictions equal to their Absurdities: for this old Fellow, who had so violent an Antipathy to some Noises, had as great a Fondness for others. Thus he is said to have been a passionate Admirer of a Drum,[17] at the same time that he always fainted at the Sound of a Musquet; and his Antipathy to the human Organs, themselves, was not without some Particularity, and, indeed, seems to have been not so much to the Sounds as to the Ideas they conveyed: of which I have heard the following Instance: One of the Waiters at the Coffee-House, whom they called young Will, was so notorious a Babbler, that it was generally thought the old Gentleman abovesaid would have insisted on his being turned away; but what was their Surprize, when they beheld him clap young Will on the Back & tip him Sixpence, crying out, That's my good Boy, for tho' thou talkest more than any Body, no Man can accuse thee of having ever said any thing.

So much for this old Coffee-House Politician: but pray, Mr Common-Sense, will you be so good to inform us, who live at this Distance, whether any of this Gentleman's Successors are yet living; whether there reigns as great[18] Silence in the Coffee-Houses [sic] at present as this Gentleman maintaind in It as long as he lived.[19] There was a great Noise some time ago concerning Spanish Depradations, which we did not like.—I do assure you, Sir, as great an Enemy as I am to Noise, I should not be displeased at the Musick

But it is now time for me to relapse into my usual Silence, therefore, after having congratulated you on yr prudent speaking but once a Week, while the Gazeteer chatters every day, I shall, in a silent Manner, assure you, I am

Yr most humble Servt,

Mum Budget

[21]

Devon, 1 April, 1738.

Notes

The only other extant literary MSS by Fielding are the two autograph poems (written c. 1729 and 1733) discovered by Isobel Grundy among the papers of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu: see "New Verse by Henry Fielding," PMLA, 87 (1972), 213-245.

In an article forthcoming in Modern Philology, Thomas Lockwood persuasively argues for Fielding's authorship of an essay entitled, "Some Thoughts on the present State of the Theatres, and the Consequences of an Act to destroy the Liberty of the Stage," published in the Daily Journal (25 March 1737) in the series called "The Occasional Prompter." Since this series was specifically devoted to theatrical affairs, Fielding presumably considered it the most appropriate forum for expressing his views on such subjects. With this issue, however, "The Occasional Prompter" ceased its run, the Daily Journal itself coming to an end on 9 April. I am grateful to Prof. Lockwood for sharing his important discovery with me.

See "Fielding Notes," MLN, 34 (1919), esp. 222-224. That Molloy wrote the leader in question is clear from the MS, which is in his hand (PRO: SP9/35, items 25-26). Molloy clinches the attribution by assigning to a "Poet" who in the context can only be Fielding, "Pasquin's" concluding simile comparing ridicule to the operations of "Ward's Pill." Cf. also Tom Jones (VIII.ix), on self-interest: "This is indeed a most excellent Medicine, and like Ward's Pill, flies at once to the particular Part of the Body on which you desire it to operate, whether it be the Tongue, the Hand, or any other Member, where it scarce ever fails of immediately producing the desired Effect" (eds. Battestin and Bowers [1975], p. 442). The "Pasquin" letter is conveniently reprinted in R. Paulson and T. Lockwood, eds. Henry Fielding: The Critical Heritage (1969), pp. 102-105; and I. Williams, ed. The Criticism of Henry Fielding (1970), pp. 23-26.

See Cross, The History of Henry Fielding (1918), I, 334 and n., III, 301; and Williams, op. cit., pp. 325-334.

The best discussion of this subject is in B. A. Goldgar, Walpole and the Wits: The Relation of Politics to Literature, 1722-42 (1976).

See William Coxe, Memoirs of the Life and Administration of Sir Robert Walpole (1800), II, 182ff.

Ibid., III, 38. The article on Yonge in the DNB provides a good summary of the qualities Fielding satirizes. An M.P. from Devon, where "Mum Budget" also resides, he was appointed Secretary at War in 1735. Walpole, it is said, "'caressed him without loving him and employed him without trusting him.'" He had a universal reputation as an unprincipled tool of the minister and as one who, in Chesterfield's words, "by a fitness of tongue raised himself successively to the best appointments in the kingdom." As Paul Whitehead characterizes him in The State Dunces (1733), however, Yonge's speeches were as empty as they were glib:

Pours forth melodious Nothings from his Tongue!

How sweet the Accents play around the Ear,

Form'd of smooth Periods, and of well-turn'd Air! (p. 14)

The Making of "Jonathan Wild", Columbia University Studies in English and Comparative Literature, No. 153 (1941), p. 117, n. 142.

Theophilus Cibber was known for his characterization of Shakespeare's Pistol (Henry IV), and from 1733-34, when he led the revolt of the actors at Drury Lane, he was often caricatured under that name. (See An Apology for the Life of Mr. T[heophilus] C[ibber], Comedian [1740], pp. 16-17.) In The Historical Register, Act II, Cibber as "Pistol" is thus introduced at the head of a mob, whom he harangues in the "Sublime" style, or rather in a ranting burlesque of heroic blank verse; in Act III he bullies his father, Ground-Ivy, this time in couplets. The characterization of "Pistol" in the letter to Common Sense is quite similar to Fielding's conception of him in the farce. That "Pistol" writes his letter from "King's Coffee-House, Covent Garden," seems to support the case for Fielding's authorship: in Tumble-Down Dick that disreputable resort is also the setting for the dance of rakes and whores who burlesque the pantomimes at Drury Lane, where "Pistol" was now acting manager. The specific occasion for the satire in Common Sense, however, was political rather than theatrical: rumor had it that Theophilus Cibber had recently assumed a new role and was scribbling Gazetteers in defense of Walpole. For the general background, as well as a comment specifically on this letter, see the Apology, Ch. IX.

The agents, Janus Brettell and Jonathan Wiggs, endorsed item 65v as follows: "Out of Mr Purser's back Parlour where he does his Bussiness 27th June 1739." Item 63 carries a similar endorsement: "June ye 28 1739 / Out of a Trunk upon the two pair of Stairs head / Mr. Molloys papers"; see also items 61, 182. Presumably referring to these seizures, Molloy made the following announcement in Common Sense (7 July 1739): "The Printer of this Paper having receiv'd an unseasonable Visit last Week,—what was design'd for the Entertainment of the Publick this Week hath been lost . . . ." What caused the raids appears to have been the leader of 23 June, which openly accused the members of Parliament of corruption and Walpole of corrupting them—and which, by the way, concludes by comparing the prime minister and his party to Wild and his gang.

See, for instance, the transcripts of his correspondence with the Duke of Bedford and his agent, in the Appendix to M. C. and R. R. Battestin, "Fielding, Bedford, and the Westminster Election of 1749," ECS, 11 (1978), 175-182.

Perfection . . . Silence] Molloy revised this to read, "Perfection that human Wisdom is capable of attaining to is, Silence".

Essay concerning Human Understanding (1690), I, iii ("No Innate Practical Principles"). Locke here demonstrates that no one "moral rule" can claim "universal assent."

Cf. Thomas Tickell in Spectator, No. 634 (17 December 1714), who calls the Stoics "the most virtuous Sect of Philosophers."

Fielding apparently confuses the Stoics with the disciples of Pythagoras, who, according to Diogenes Laertius, required that his scholars prepare themselves as philosophers by keeping silent for five years (Lives of Eminent Philosophers, VIII, 10). Addison speaks of their "Apprenticeship of Silence" in Spectator, No. 550 (1 December 1712), to which Fielding alludes later in this essay. See also Thomas Stanley, History of Philosophy, 3rd ed. (1701), pp. 358, 372; and André Dacier, Life of Pythagoras (1707), pp. 24-26.

Iliad, III.8: "But the Achaeans came on in silence, breathing fury . . ." (trans. A. T. Murray, Loeb Classical Library, 1946).

"The day would be too short if I wished to run through them all." Fielding apparently paraphrases Cicero's De Natura Deorum, III, xxxii, 81: "Dies deficiat si velim enumerare . . . ." With the present passage, compare The Covent-Garden Journal (7 January 1752): "Such are, in short, the Virtues of this Age; that, to use the Words of Cicero, Si vellem [sic] omnia percurrere Dies deficeret—I shall therefore omit the rest . . . ."

From the first number Mr. Spectator claims to have distinguished himself by keeping a "most profound Silence," a trait which earns him the reputation of "a dumb Man" (No. 4, 5 March 1711). In the present passage Fielding especially recalls No. 550 (1 December 1712), where Mr. Spectator remarks: "As a Monosyllable is my Delight, I have made very few Excursions in the Conversations which I have related beyond a Yes or a No." In founding a new club, however, he intends to be more talkative in the future: "But that I may proceed the more regularly in this Affair, I design upon the first Meeting of the said Club to have my Mouth opened in Form, intending to regulate my self in this Particular by a certain Ritual which I have by me, that contains all the Ceremonies which are practised at the opening the Mouth of a Cardinal." (D. F. Bond, ed. [1965], IV, 470-471.)

In An Argument against the Abolishing of Christianity in England (1708), Swift assures his readers that he wishes to preserve only "nominal," not "real" Christianity, the latter "having been for some time wholly laid aside by general Consent, as utterly inconsistent with our present Schemes of Wealth and Power" (H. Davis, ed. Bickerstaff Papers and Pamphlets on the Church [1957], p. 28).

In Act III of The Historical Register Fielding ridiculed Walpole in the character of Quidam, who, though not exactly silent, is more remarkable for his actions than his words: after winning over some disaffected Patriots with a bribe, he produces a fiddle and leads them all in a dance.

This famous legend about the philosopher Roger Bacon (1214?-94) was dramatized by Robert Greene in Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay (1594). Friar Bacon, it is said, made a head of brass and with the Devil's help gave it speech. The allusion here is doubly apt, Walpole being known to the Opposition as "Bob Brass."

Cf. the obscure political allegory in Common Sense (24 September 1737), referring to one "Gaspar Cornaro," a Venetian empiric: "Your Wits have abundance of By-names for him; as . . . Haberdasher of Small Wit, &c."

Presumably a pun: a "Drum" was a large party usually held in the evening for the purpose of playing at cards. Fielding often ridicules this fashionable diversion: e.g. True Patriot (28 January 1746), Tom Jones (XVII,vi), Amelia (IX,vii).

maintaind . . . lived.] Molloy obliterated Fielding's phrasing beyond recovery and substituted these words. This change may have caused the apparent error in the plural form "Coffee-Houses" earlier in the sentence.

The OED surmises that "mumbudget" was originally a children's game in which silence was required. Examples include The Merry Wives of Windsor (1598), V.ii.7; Butler's Hudibras (1663), I.iii.208; and John Taylor, the Water Poet (1630): "The magazin of taciturnitie, the mumbudget of silence. . . ." "Budget" signifying a pouch or wallet, the phrase "to open one's budget" in colloquial usage means "to speak one's mind."

| | ||