| | ||

3.

Simple as the bibliographical technique is of using an ornament chart to identify the unsigned books of a printer, it has occasionally its pitfalls, and hence for the guidance of bibliographers

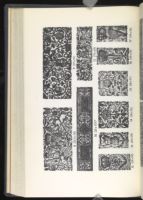

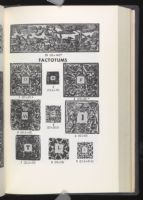

English ornament makers of this period show a marked tendency to copy and recopy earlier designs rather than create new ones. Those copies made in wood are more often than not distinguishable from each other, but on occasion recuttings were made with such precision that one is hard put to tell them apart. The many decorations made from metal rather than wood present a greater problem in that indistinguishable copies of an ornament cast from the same matrix were owned and regularly used by as many as a half-dozen printers. Wherever I have found a printer using an ornament very similar to Newcomb's, I have made a note of it after the list of occurrences; but since I have concentrated in this study on the ornaments of only a handful of printers and since there are tens of thousands of books which I have not seen, the likelihood is that future study will uncover very similar or indistinguishable copies of Newcomb ornaments in the stock of other printers.

Measurements of ornaments are helpful in distinguishing between like ornaments but furnish conclusive evidence only where there is a marked difference in size between two otherwise identical ornaments. Different impressions of the same ornament vary in measurement because of light or heavy inking, newness or wear, or variable degrees of shrinkage in the paper. In the Newcomb chart I have at times given measurements down to a half millimeter; one should not, however, consider them other than the average, often made up from several varying measurements.

A knowledge of printers' type-ornaments is generally useless in attempting to identify a particular printer in this period. I have found no one of Newcomb's many type-ornaments that was not also in the stock of other printers.

When the identification of the printer of an unsigned book depends on the decorative initials H, I, O, or S, one should be sure to examine the letter both right side up and upside down. Compositors paid little attention to the proper position of such letters, and looked at wrong side up, these letters often present quite a different appearance.

Ornaments in the text of a volume occasionally qualify or contradict the evidence of a printer's name in the title-page imprint.

Finally, in attributing to a specific printer the presswork of an unsigned book, one is always on surer ground if he can buttress the evidence of the ornamentation with that derived from other reliable sources. One of the obvious sources is the printer-employment habits of the stationer publishing the book. A study of the imprints on books published by Herringman, for example, reveals that he tended to patronize one or two printers consistently in a given period. Therefore anyone attempting to identify the printer of a Herringman volume can eliminate from consideration almost immediately all but the handful of likely candidates; and where the volume in question contains ornaments known to be used by several printers, one can on occasion establish with great probability the one printer whom Herringman hired to do his work.

The other source is the wills of the printers with the appended probate statements. Ornament stocks seem to have passed almost overnight from one printer to another, and therefore it is frequently necessary to determine the terminal dates of a printer's activity, lest one interpret the evidence of the ornaments erroneously. For instance, the evidence of ornaments supported by that of the imprints suggests that Thomas Newcomb, Sr., was active as a printer from 1648 to 1691. The probate date of his will indicates, however, that he died late in 1681, and the text of the will points to the fact that Newcomb's son, who happened to have the same name as his father's, inherited the ornament stock and was

| | ||