| CHAPTER II.

THE ARREST OF PRIVATE MILES. The life and adventures, songs, services, and

speeches of Private Miles O'Reilly [pseud.] (47th regiment, New York

volunteers.) | ||

2. CHAPTER II.

THE ARREST OF PRIVATE MILES.

My Dear Hudson: A most ridiculous incident has

occurred here, which nevertheless threatened,

but for the prompt measures adopted by Lieutenant-Colonel

J. F. Hall, Provost Marshal General, to have

resulted, perhaps, in a weakening of the strong regard

which has heretofore subsisted between our land

and naval forces. The facts are as follows:—

There is in one of the New York regiments an odd

character named Miles O'Reilly, who has frequently

relieved the monotony of camp life by scribbling

songs on all sorts of subjects, and writing librettos for

the various “minstrel companies,” got up in imitation

of George Christy's, at different posts of the

Department during periods of repose.

His last effort was a song, advising Admiral Dahlgren

to go home, and warmly espousing the interests

of Admiral Du Pont and the former commanders of

the iron-clads, in whose behalf his affections seem

warmly enlisted, he having served for some months

as a volunteer marine on board the Pawnee, Wabash,

Ironsides, Paul Jones, and other vessels of the South

Atlantic Blockading Squadron.

These verses he managed in some mysterious manner

to have printed in regular street ballad form,

either on the press of Mr. J. H. Sears, at Hilton

Head; or, more probably, in the office of General

Saxton's Free South, at Beaufort. At any rate he got

them printed, and they soon were in the hands of

nearly every soldier—the men singing them with intense

and uproarious relish to an old Irish air, slightly

altered — the Shan Van Voght, which Private

O'Reilly taught them.

At last the song attracted the attention of some naval

officers who were ashore on a visit to Col. J. W.

Turner, “a corn-fed boy from Illinoy,” and Col. J. J.

Elwell, Chief Quartermaster of the Department; and

they, having mentioned the matter to some army

associates, Col. J. F. Hall was very quickly on the

track of the author, and had no difficulty in tracing

the squib to O'Reilly, who was at once placed in

confinement, with a sixty-four pound shot at each

heel, to aid, perhaps, in preventing any further

Pegasinian or Olympian flights. He takes his punishment

good-humoredly; compares himself to Galileo,

“an ould cock that was tortured for telling the

thruth;” and is at present busily writing an appeal

in verse to Secretary Stanton. In order that you

may be able to judge of the enormity of the breach

of discipline of which O'Reilly has been guilty, I

transmit herewith a printed copy of his song:—

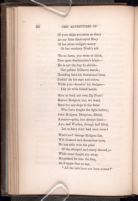

THE ARMY TO THE IRON-CLADS.

(With an accompaniment of bombshells, Greek fire, and two hundred

pounder rifled shots.)

It is aisy to be seen

That ashore so long you've been

You can never toe the mark;

As my little black-eyed Mary

Of her silver-winged canary

Or her crockery Noah's ark.

'Tis no harm, you seem to think,

That upon desthruction's brink—

He is not the boy to shrink—

Our gallant Gillmore stands;

Houlding hard his threatened lines,

Pushin' far his saps and mines,

While you—knowin' his designs—

Idly sit with folded hands.

Give us back our own Du Pont!

Ramon Rodgers, too, we want,

Send the say-dogs to the front

Who have fought the fight before;

John Rodgers, Dhrayton, Rhind,

Ammen—grim, but always kind—

Aye, and Worden, though half blind,

Let us have their lead once more!

Woe's me! George Rodgers lies,

Wid dimmed and dhreamless eyes,

He has airly won the prize

Of the sthriped and starry shroud;—

While some fought shy away

He pushed far into the fray,

As if ayger thus to say,

“All the lads have not been cowed!”

Born layguerers of towns!

“No chance here of laurel crowns,”

Thus it seems I hear you sighin';

“'Twas not always so,” you say,

“When Du Pont in every fray

Led the line and cleared the way,

Wid his broad blue pennon flyin'.”

Och! Gideon, King of men!

Take Dahlgreen home again,

And let Fulton's glowin' pen

All his high achavements blazon—

For Fulton, Gideon mine!

Can paint pictures, line by line,

All of that precise design

You and Fox delight to gaze on.

Dear Uncle Gideon, oh!

Let Dahlgreen homeward go!

He's a shmart man, as we know,

And the guns he makes are sthriking;

Keep him always on the make,

Do, Gid, for pity's sake;

But the warrior lead to take,

Let us have Du Pont, the Viking!

What disposition will eventually be make of private

Miles O'Reilly, who has twice risen to sergeant

discipline, it would be hard to guess. Lieutenant

Colonel E. W. Smith, General Gillmore's Assistant

Adjutant General, is at a loss to know under what

article of war the crime of song-writing can be punished.

Officers of a naturally severe cast of countenance

will also be required to avoid unseemly

laughter during the sessions of the court. Besides,

there is a strong feeling, I regret to say, among all

the men and many of the subordinate officers in

O'Reilly's favor: and while many, wearing the

double rows of buttons, declare he should be severely

dealt with, very nearly all the single-breasted

coats, with or without shoulder-straps, think it would

do no injury to postpone his trial until after an article

of war against song writing shall have been

added to those now in force by the next Congress.

It is rumored that copies of the song in question

have permeated the navy, and that nearly all the

wardroom messes have under discussion the propriety

of signing a petition for O'Reilly's release. Meantime

it is difficult, even for Colonel Hall, to enforce

that rigorous treatment of the prisoner which he is

thought to deserve, as the soldiers, to a man, believe

he is unfairly punished; and the provost guard have

prescribed and proper daily diet being eighteen

ounces of bread with two quarts of cold water.

General A. H. Terry, we hear, offers to release the

prisoner if he will disclose the name of the printer

of his incendiary song. This offer O'Reilly indignantly

spurns, saying he “never sould the pass in

his life, nor never will;” and winds up by asking

do they take him for a “soup kitchen convert,” or

one of “Lord Clarendon's Jimmy O'Briens.” These

phrases are all Greek to us down here, even in this

region of Greek fire; but mayhap “Irish Tom,”

opposite the Custom House, may be able to translate

them into English.

Before quitting this subject, let me say that the

attempts made in certain quarters to exalt the present

achievements of the South Atlantic Blockading

Squadron, at the expense of its late commander,

Admiral Du Pont, will have an effect rather the

reverse of that intended by those who are engaged

in this paltry business. No one whose authority in

such matters is of any weight, thinks of blaming

Admiral Dahlgren for the extreme caution he has

thus far displayed in exposing his iron-clads to fire.

He ranks second to no officer in the navy as a commander

hands are utterly inadequate to the work they are

expected to accomplish; and, in taking him out of

the Ordnance Bureau of the Navy, in which his services

have been invaluable for the last fifteen or

twenty years, and placing him suddenly, and with

but little actual sea-experience, in command of so

vast an undertaking as this of Charleston,—it is felt

that Secretary Welles has committed his favorite

error of placing the right man in the wrong place,

and imposing upon Dahlgren a task under which he

must most certainly break down.

It is well understood by all here that, with the

destruction of Fort Sumter and the capture of Forts

Wagner and Gregg, the main business of the land

forces under General Gillmore will have been accomplished.

Indeed, this is all General Gillmore bargained

to do when making those representations

which resulted in his appointment to the command.

Nothing will then remain for him but to shell

Charleston, at long range, from Cumming's Point;

and here, en parenthèse, let me remark that the accident

to the three hundred pounder Parrott gun does

not, as was at first supposed, at all disable that gun.

The injury was received from the untimely bursting

This accident blew off the muzzleband; but the

remainder of the piece is uninjured, and in as good

condition as ever for practical work.

And now to return to the iron-clad matter, of

which I set out to speak. It is not generally known,

but is nevertheless true, that Admiral Dahlgren is, and

has been for the last ten days, confined to his bed by

sickness, or has only been able to crawl on deck or

into the pilot-house on critical occasions. The

abominable atmosphere of the iron-clads has taken

hold of his system, and nothing but his high resolution,

and the necessity he is under of vindicating the

action of the Navy Department, which placed him

in command, can long sustain him under his present

debility. So fixed is his determination to go through

with his work, however, that he has not in any of his

dispatches to the Department even referred to his ill-health;

and it is only by private letters from sympathizing

friends that the North can hear of his condition.

He doubtless feels that, under the peculiar circumstances

attending Du Pont's removal, a more than

common anxiety must be felt by the Navy Department

for the exertions to the uttermost of the

officer who has succeeded the victor of Port

Sumter.

In Du Pont's attack, it must be remembered,

all the iron-clads ran up to within eight hundred

yards of the then uninjured fort,—Captain Rhind,

in the ill-fated Keokuk, running in to within four

hundred yards, and fighting desperately for thirty

minutes at that distance, only withdrawing under

orders, and at a moment when his vessel was a sinking

ruin;—while in the present operations, assisted

by Gillmore's powerful land batteries, Admiral Dahlgren,

reserving his vessels for work farther up the

roadstead, has wisely held them not closer than two

thousand yards to Fort Sumter, while that work was

still in a condition to reply effectively to his fire—

two thousand yards being very nearly the extreme

effective range of his fifteen-inch smooth bores.

Under these circumstances, Du Pont may possibly

be condemned for rashness, or Dahlgren commended

for prudence; but it is obviously worse than

absurd to indulge in any sneers or indirect innuendoes

or cavils against Du Pont's attack as if it had

lacked in gallantry. The Old Viking of the South

Atlantic blockading squadron is the last man in the

world among his peers—men personally acquainted

—to whom such a charge will stick. No braver or

more intelligent officers ever lived than his subordinate

iron-clad commanders—John Rodgers, Rhind,

Drayton, Fairfax, Ammen, Downs, Worden, Turner,

and the lamented George W. Rodgers, who lost his

life, as you are aware, while running his vessel in

to within one hundred and fifty yards of Fort

Wagner.

There is one point, however, in Admiral Dahlgren's

course which excites a good deal of laughing commentary

among our army officers. It is this:—On

the 23d inst. Colonel John W. Turner, the “corn fed

boy from Illinoy,” who is General Gillmore's chief

of staff and of artillery, ceases fire against Fort Sumter,

on the ground that it is an inoffensive ruin,

which could be still more completely made a pile of

broken brick and powdered mortar by further fire;

but which could not, by any amount of fire, be rendered

more completely harmless as against the iron-clads

than in its then condition. The day after this,

on the 24th inst., the iron-clads, idle or only firing at

long range during the previous ten days against this

particular fort, announced their intention of making

“an attack in force on the work,” and our army

York papers will some day tell you of the “Surrender

of Fort Sumter to the iron-clads” in startling

capitals,—the announcement adding that on such a

day so many hundred marines and seamen “landed

on the ruined ramparts, and, gallantly climbing

over the shattered arches and parades, hoisted the

Stars and Stripes and took possession of the work in

the name of the navy—another glorious victory to

the—marines!” The western officers in particular

are strong in this belief. They say they saw the

same thing done at Island No. Ten; and on this

point, but in connexion with the siege of Vicksburg,

they tell a story which is rather hard upon the “bummers,”

or mortar schooners and gunboats, employed

in the reduction of that place.

They say that Lieutenant-General Pemberton once

asked Grant for a truce to bury his dead outside the

works. This was while Grant was attacking from the

land circumvallation, while the naval forces were

throwing shells high up in the air to fall down over

the bluffs into the devoted city. Grant answered

that he had no objection, but would require some

hours to consult with Admiral Porter, in order to

have the navy cease firing as well as the land forces.

never mind it,” was the prompt answer of the rebel

negotiator. “If your land batteries on a level with

us will only stop, the bummers and gunboats may

keep firing at the moon until the day of Judgment.”

The same Western officers further allege that the

same principle which would justify the navy in claiming

Fort Sumter as their prize, was amply illustrated

in the flaming bulletins which announced the capture

of the Haines Bluff batteries, after they had been evacuated

under the stress put upon them through General

Sherman's corps, by the Mississippi flotilla.

These remarks, I am fully aware, are extremely ill-natured,

and may even appear frivolous to men who

cannot understand that honor is the highest prize for

which our soldiers and sailors are contending. But

beyond doubt there cannot be so much smoke without

fire; and it is for the best interests of both branches

of the service that each should know the alleged

points of grievance between them. The navy has

such an abundance of laurels, that none of its true

friends—and I claim to be one of its truest—could

wish to deprive the army of a single twig or leaf that

is justly due to it.

As for other matters, the wisest here think that

Charleston conflict will be abundantly justified when

the nature of the work yet to be accomplished is

understood by the public. Fort Sumter—weakest

for defence, most powerful for the offensive—is now

happily eliminated from the problem which the iron-clads

have yet to solve. But Forts Moultrie and

Johnson, Battery Bee, Battery Beauregard, Castle

Pinckney and Fort Ripley, still remain to be settled

with; and in the attack upon these General Gillmore

can give but little assistance. Against Fort Moultrie,

the strongest defensive work in the harbor, he

can do almost nothing. Fort Johnson is on the

extreme left of Beauregard's line of defences, stretching

across James Island from the harbor line to Secessionville.

To attack this line in general would require

a force more than treble that now at Gen. Gillmore's

disposal; and his only means of advancing

under cover against the fort, would be to start

trenches, zigzags and parallels from where the Swamp

Angel Battery is now located, along the narrow strip

of hard sand-shore which lies between the swamps

and the harbor-line. This strip of hard sand would

offer very nearly the same obstacle to trenching that

would be offered by the pavements and sub-soil of

labors they have already performed, and the malarial

cachexia which has reduced their systems, it is

doubtful if his whole force, applied to the spade and

pick for the next three months, would suffice to advance

a mine under the walls of Fort Johnson. Most

probably—indeed almost certainly—Gen. Gillmore,

on obtaining possession of Cummings' Point, will

open at long range with his three, two, and one hundred

pounder Parrots against Charleston city, keeping

his troops in a state of tranquil amusement, while

watching the effects of Greek fire amongst the buildings

of Meeting and King streets; and generously

admiring the splendid exertions of courage, labor, and

science by which his confrères of the navy propose

to remove the various lines of torpedo-armed obstructions

now blocking up Charleston harbor.

| CHAPTER II.

THE ARREST OF PRIVATE MILES. The life and adventures, songs, services, and

speeches of Private Miles O'Reilly [pseud.] (47th regiment, New York

volunteers.) | ||