Sevenoaks a story of to-day |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. | CHAPTER III.

IN WHICH JIM FENTON IS INTRODUCED TO THE READER AND

INTRODUCES HIMSELF TO MISS BUTTERWORTH. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. |

| 30. |

| CHAPTER III.

IN WHICH JIM FENTON IS INTRODUCED TO THE READER AND

INTRODUCES HIMSELF TO MISS BUTTERWORTH. Sevenoaks | ||

3. CHAPTER III.

IN WHICH JIM FENTON IS INTRODUCED TO THE READER AND

INTRODUCES HIMSELF TO MISS BUTTERWORTH.

Miss Butterworth, while painfully witnessing the defeat

of her hopes from the last seat in the hall, was conscious of

the presence at her side of a very singular-looking personage,

who evidently did not belong in Sevenoaks. He was a woodsman,

who had been attracted to the hall by his desire to witness

the proceedings. His clothes, originally of strong material,

were patched; he held in his hand a fur cap without a

visor; and a rifle leaned on the bench at his side. She had

been attracted to him by his thoroughly good-natured face,

his noble, mascular figure, and certain exclamations that

escaped from his lips during the speeches. Finally, he turned

to her, and with a smile so broad and full that it brought an

answer to her own face, he said: “This 'ere breathin' is worse

nor an old swamp. I'm goin', and good-bye to ye!”

Why this remark, personally addressed to her, did not

offend her, coming as it did from a stranger, she did not

know; but it certainly did not seem impudent. There was

something so simple and strong and manly about him, as he

had sat there by her side, contrasted with the baser and better

dressed men before her, that she took his address as an

honorable courtesy.

When the woodsman went out upon the steps of the town-hall,

to get a breath, he found there such an assembly of boys

as usually gathers in villages on the smallest public occasion.

Squarely before the door stood Mr. Belcher's grays, and in

Mr. Belcher's wagon sat Mr. Belcher's man, Phipps. Phipps

horses, proud of his clothes, proud of the whip he was carelessly

snapping, proud of belonging to Mr. Belcher. The

boys were laughing at his funny remarks, envying him his

proud eminence, and discussing the merits of the horses and

the various points of the attractive establishment.

As the stranger appeared, he looked down upon the boys

with a broad smile, which attracted them at once, and quite

diverted them from their flattering attentions to Phipps—a

fact quickly perceived by the latter, and as quickly revenged

in a way peculiar to himself and the man from whom he had

learned it.

“This is the hippopotamus, gentlemen,” said Phipps,

“fresh from his native woods. He sleeps underneath the

banyan-tree, and lives on the nuts of the hick-o-ree, and pursues

his prey with his tail extended upward and one eye open,

and has been known when excited by hunger to eat small

boys, spitting out their boots with great violence. Keep out

of his way, gentlemen! Keep out of his way, and observe his

wickedness at a distance.”

Phipps's saucy speech was received with a great roar by the

boys, who were surprised to notice that the animal himself

was not only not disturbed, but very much amused by being

shown up as a curiosity.

“Well, you're a new sort of a monkey, any way,” said

the woodsman, after the laugh had subsided. “I never

hearn one talk afore.”

“You never will agian,” retorted Phipps, “if you give

me any more of your lip.”

The woodsman walked quickly toward Phipps, as if he

were about to pull him from his seat.

Phipps saw the motion, started the horses, and was out of

his way in an instant.

The boys shouted in derision, but Phipps did not come

back, and the stranger was the hero. They gathered around

him, asking questions, all of which he good-naturedly answered.

were only a big boy himself, and wanted to make the most

of the limited time which his visit to the town afforded

him.

While he was thus standing as the center of an inquisitive

and admiring group, Miss Butterworth came out of the town-hall.

Her eyes were full of tears, and her eloquent face expressed

vexation and distress. The stranger saw the look and

the tears, and, leaving the boys, he approached her without

the slightest awkwardness, and said:

“Has anybody teched ye, mum?”

“Oh, no, sir,” Miss Butterworth answered.

“Has anybody spoke ha'sh to ye?”

“Oh, no, sir;” and Miss Butterworth pressed on, conscious

that in that kind inquiry there breathed as genuine

respect and sympathy as ever had reached her ears in the

voice of a man.

“Because,” said the man, still walking along at her side,

“I'm spilin' to do somethin' for somebody, and I wouldn't

mind thrashin' anybody you'd p'int out.”

“No, you can do nothing for me. Nobody can do anything

in this town for anybody until Robert Belcher is dead,”

said Miss Butterworth.

“Well, I shouldn't like to kill 'im,” responded the man,

“unless it was an accident in the woods—a great ways off—

for a turkey or a hedgehog—and the gun half-cocked.”

The little tailoress smiled through her tears, though she felt

very uneasy at being observed in company and conversation

with the rough-looking stranger. He evidently divined the

thoughts which possessed her, and said, as if only the mention

of his name would make him an acquaintance:

“I'm Jim Fenton. I trap for a livin' up in Number Nine,

and have jest brung in my skins.”

“My name is Butterworth,” she responded mechanically.

“I know'd it,” he replied. “I axed the boys.”

“Good-bye,” he said. “Here's the store, and I must

I'm fond of 'em, and they're pretty apt to like me.”

“Good-bye,” said the woman. “I think you're the best

man I've seen to-day;” and then, as if she had said more

than became a modest woman, she added, “and that isn't

saying very much.”

They parted, and Jim Fenton stood perfectly still in the

street and looked at her, until she disappeared around a

corner. “That's what I call a genuine creetur',” he muttered

to himself at last, “a genuine creetur'.”

Then Jim Fenton went into the store, where he had sold

his skins and bought his supplies, and, after exchanging a few

jokes with those who had observed his interview with Miss

Butterworth, he shouldered his sack as he called it, and started

for Number Nine. The sack was a contrivance of his own,

with two pouches which depended, one before and one

behind, from his broad shoulders. Taking his rifle in his

hand, he bade the group that had gathered around him a

hearty good-bye, and started on his way.

The afternoon was not a pleasant one. The air was raw,

and, as the sun went toward its setting, the wind came on to

blow from the north-west. This was just as he would have it.

It gave him breath, and stimulated the vitality that was necessary

to him in the performance of his long task. A tramp

of forty miles was not play, even to him, and this long distance

was to be accomplished before he could reach the boat

that would bear him and his burden into the woods.

He crossed the Branch at its principal bridge, and took the

same path up the hill that Robert Belcher had traveled in the

morning. About half-way up the hill, as he was going on

with the stride of a giant, he saw a little boy at the side of

the road, who had evidently been weeping. He was thinly

and very shabbily clad, and was shivering with cold. The great,

healthy heart within Jim Fenton was touched in an instant.

“Well, bub,” said he, tenderly, “how fare ye? How fare

ye? Eh?”

“I'm pretty well, I thank you, sir,” replied the lad.

“I guess not. You're as blue as a whetstone. You haven't

got as much on you as a picked goose.”

“I can't help it, sir,” and the boy burst into tears.

“Well, well, I didn't mean to trouble you, boy. Here,

take this money, and buy somethin' to make you happy.

Don't tell your dad you've got it. It's yourn.”

The boy made a gesture of rejection, and said: “I don't

wish to take it, sir.”

“Now, that's good! Don't wish to take it! Why, what's

your name? You're a new sort o' boy.”

“My name is Harry Benedict.”

“Harry Benedict? And what's your pa's name?”

“His name is Paul Benedict.”

“Where is he now?”

“He is in the poor-house.”

“And you, too?”

“Yes, sir,” and the lad found expression for his distress in

another flow of tears.

“Well, well, well, well! If that ain't the strangest thing I

ever hearn on! Paul Benedict, of Sevenoaks, in Tom Buffum's

Boardin'-house!”

“Yes, sir, and he's very crazy, too.”

Jim Fenton set his rifle against a rock at the roadside, slowly

lifted off his pack and placed it near the rifle, and then sat

down on a stone and called the boy to him, folding him in

his great warm arms to his warm breast.

“Harry, my boy,” said Jim, “your pa and me was old

friends. We have hunted together, fished together, eat together,

and slept together many's the day and night. He was the best

shot that ever come into the woods. I've seed him hit a deer

at fifty rod many's the time, and he used to bring up the nicest

tackle for fishin', every bit of it made with his own hands.

He was the curisist creetur' I ever seed in my life, and the best;

and I'd do more fur 'im nor fur any livin' live man. Oh, I

tell ye, we used to have high old times. It was wuth livin' a

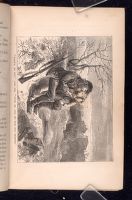

“Harry, my boy, said Jim, your pa an' me was old friends.”

[Description: 590EAF. Illustration page. Image of a man sitting on a rock with his arms around a young boy. A rifle leans next to the man.]

never charged 'im a red cent fur nothin', and I've got some

of his old tackle now that he give me. Him an' me was like

brothers, and he used to talk about religion, and tell me I

ought to shift over, but I never could see 'zactly what I ought

to shift over from, or shift over to; but I let 'im talk, 'cause

he liked to. He used to go out behind the trees nights, and

I hearn him sayin' somethin'—somethin' very low, as I am

talkin' to ye now. Well, he was prayin'; that's the fact

about it, I s'pose; and ye know I felt jest as safe when that

man was round! I don't believe I could a' been drownded

when he was in the woods any more'n if I'd a' been a mink.

An' Paul Benedict is in the poor-house! I vow I don't

'zactly see why the Lord let that man go up the spout; but

perhaps it'll all come out right. Where's your ma, boy?”

Harry gave a great, shuddering gasp, and, answering him

that she was dead, gave himself up to another fit of crying.

“Oh, now don't! now don't!” said Jim tenderly, pressing

the distressed lad still closer to his heart. “Don't ye do

it; it don't do no good. It jest takes the spunk all out o'

ye. Ma's have to die like other folks, or go to the poor-house.

You wouldn't like to have yer ma in the poor-house.

She's all right. God Almighty's bound to take

care o' her. Now, ye jest stop that sort o' thing. She's

better off with him nor she would be with Tom Buffum—any

amount better off. Doesn't Tom Buffum treat your pa well?”

“Oh, no, sir; he doesn't give him enough to eat, and he

doesn't let him have things in his room, because he says he'll

hurt himself, or break them all to pieces, and he doesn't give

him good clothes, nor anything to cover himself up with when

it's cold.”

“Well, boy,” said Jim, his great frame shaking with indignation,

“do ye want to know what I think of Tom Buffum?”

“Yes, sir.”

“It won't do fur me to tell ye, 'cause I'm rough, but if

there's anything awful bad—oh, bad as anything can be, in

Skeezacks.”

Jim Fenton was feeling his way.

“I should say he was an infernal old Skeezacks. That

isn't very bad, is it?”

“I don't know sir,” replied the boy.

“Well, a d—d rascal; how's that?”

“My father never used such words,” replied the boy.

“That's right, and I take it back. I oughtn't to have said

it, but unless a feller has got some sort o' religion he has a

mighty hard time namin' people in this world. What's that?”

Jim started with the sound in his ear of what seemed to be

a cry of distress.

“That's one of the crazy people. They do it all the time.”

Then Jim thought of the speeches he had heard in the

town-meeting, and recalled the distress of Miss Butterworth,

and the significance of all the scenes he had so recently

witnessed.

“Look 'ere, boy; can ye keep right 'ere,” tapping him

on his breast, “whatsomever I tell ye? Can you keep yer

tongue still?—hope you'll die if ye don't?”

There was something in these questions through which the

intuitions of the lad saw help, both for his father and himself.

Hope strung his little muscles in an instant, his attitude

became alert, and he replied:

“I'll never say anything if they kill me.”

“Well, I'll tell ye what I'm goin' to do. I'm goin' to

stay to the poor-house to-night, if they'll keep me, an' I

guess they will; and I'm goin' to see yer pa too, and somehow

you and he must be got out of this place.”

The boy threw his arms around Jim's neck, and kissed him

passionately, again and again, without the power, apparently,

to give any other expression to his emotions.

“Oh, God! don't, boy! That's a sort o' thing I can't

stand. I ain't used to it.”

Jim paused, as if to realize how sweet it was to hold the

said: “Ye must be mighty keerful, and do just as I bid ye.

If I stay to the poor-house to-night, I shall want to see ye in

the mornin', and I shall want to see ye alone. Now ye

know there's a big stump by the side of the road, half-way up

to the old school-house.”

Harry gave his assent.

“Well. I want ye to be thar, ahead o' me, and then I'll

tell ye jest what I'm a goin' to do, and jest what I want to

have ye do.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Now mind, ye mustn't know me when I'm about the

house, and mustn't tell anybody you've seed me, and I mustn't

know you. Now ye leave all the rest to Jim Fenton, yer

pa's old friend. Don't ye begin to feel a little better now?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You can kiss me again, if ye want to. I didn't mean

to choke ye off. That was all in fun, ye know.”

Harry kissed him, and then Jim said: “Now make tracks

for yer old boardin'-house. I'll be along bimeby.”

The boy started upon a brisk run, and Jim still sat upon the

stone watching him until he disappeared somewhere among

the angles of the tumble-down buildings that constituted the

establishment.

“Well, Jim Fenton,” he said to himself, “ye've been

spilin' fur somethin' to do fur somebody. I guess ye've got

it, and not a very small job neither.”

Then he shouldered his pack, took up his rifle, looked up

at the cloudy and blustering sky, and pushed up the hill, still

talking to himself, and saying: “A little boy of about his

haighth and bigness ain't a bad thing to take.”

| CHAPTER III.

IN WHICH JIM FENTON IS INTRODUCED TO THE READER AND

INTRODUCES HIMSELF TO MISS BUTTERWORTH. Sevenoaks | ||