Kate Beaumont with illustrations |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. |

| 30. |

| 31. | CHAPTER XXXI. |

| 32. |

| 33. |

| 35. |

| 36. |

| 37. |

| 38. |

| 39. |

| CHAPTER XXXI. Kate Beaumont | ||

31. CHAPTER XXXI.

It must be remembered that Randolph

Armitage had passed several days on the

verge of delirium tremens, either caring nothing

for the exodus of his wife and children,

or anaware of it.

But on recovering his wits he wanted

his Israel back, as is apt to be the case

with abandoned Pharaohs of our household

Egypts, however vicious and unloving they

may be. It is such a disgrace to be deserted,

and involves such a diminution of

sweet authority, besides loss of domestic

comforts!

Conceited, confident in himself, passionately

wilful and headlong, he soon determined

to go in pursuit of Nellie, believing

that at the sight of him she would fall under

the old fascination and return to her

wifely allegiance. Bentley objected, but

only a little; for not only was he afraid of

his brother, but he was in love with Kate;

and loving Kate, he could not desire that

Armitages and Beaumonts should be separated

forever.

Sober when he left home, Randolph was

quiet in demeanor and even somewhat anxious

in spirit. He feared lest his wife or her

sister might have told tales on him; and, if

that were the case, he would probably have

to listen to a remonstrance from “old man

Beaumont”; and he knew that when that

gentleman did remonstrate, it was in the style

of a tornado. But with the fatuity of a shallow

soul, incapable of appreciating its own

scoundrelism, or of putting itself fairly in

the place of another, he trusted that he

could easily turn wrath into favor by a week

of sobriety and of the superfine deportment

assume.

At Brownville he heard for the first time

that Frank had met Nellie there and gone

on with her to Hartland. The news was

angering; the man, being a McAlister, had

no right to travel with his family; moreover,

it looked as if he had helped the woman to

run away. Randolph took a drink and then

several drinks. By the time the train

started (it was early in the morning, observe)

he was in a state to go on drinking.

He treated himself at every station, and he

accepted treats from fellow-passengers who

carried bottles in their wayfarings, as is the

genial habit of certain Southerners. Long

before he reached Hartland he was fit to

shoot an enemy on sight, and to see an

enemy in the first man who stared at him.

He forgot that the object of his journey was

to wheedle back his wife to her married

wretchedness. His inflamed brain settled

down upon the idea that it was his duty as

a gentleman to chastise Frank McAlister

for abetting Nellie's elopement, and for

daring to associate himself to Beaumonts.

Clenching his first and muttering, he carried

on imaginary conversations with that criminal,

reproving him for his impertinence and

threatening punishment.

“You 've no call to speak to a Beaumont,”

he babbled, identifying himself with

the famous family feud, for which when

sober he did not care a picayune. “My

wife is a Beaumont, sir. She 's above you,

sir. My people have nothing to do with

your people. I 'm a Beaumont — by kinsmanship.

You sha' n't travel with my wife,

sir. You sha' n't go in the same car with

her. You sha' n't lead her away from her

home and her husband. We 'll settle this

matter, sir. We 'll settle it now, sir.” And

so on.

At the Hartland station his first inquiry

was for Mr. Frank McAlister. “Never saw

him in my life,” he explained. “Don't

know him from Adam. But he 's a tall fellow.

He 's a scoundrel. I 'm after him,

I 'm on his trail. Seen anything of him?”

Frank's person was more exactly described

to him by a little, red-eyed, seedy

old gentleman, who seemed to be doing

“the dignified standing round” in the grocery

attached to the station, and in whom

we may no doubt recognize General Johnson.

The General, smelling an affair of

honor, and always willing to give chivalry

a lift, made prompt inquiries as to the

whereabouts of young McAlister, and presently

brought word that he had been seen

only half an hour before riding in the direction

of the Beaumont territories.

“Gone to attack my relatives!” muttered

the drunkard, honestly believing at the

moment that he loved the Beaumonts.

“I 'll be there. I 'm on his trail. I 'll be

there.”

He was as mad as Don Quixote. He was

in a state to succor people who did not want

to be succored, and to right wrongs which

had never been given, and to see a caitiff in

every chance comer. He was one of those

knight-errants who are created by the accolade

of a bottle.

Reaching the castle which he meant to

save, just as Frank, Beaumont, and Kershaw

came out of it, he had no difficulty in

recognizing his proposed victim. The obvious

amicableness of the interview did not

in the least enlighten this lunatic. In the

smiling and happy young man, who was

shaking hands with the master of the house,

he could only see a villain who had deeply

injured himself, and who was now assaulting

or insulting his wife's relatives. Clapping

his hand on the but of his revolver,

he strode, or rather staggered, towards

Frank, scarcely observing Beaumont and

Kershaw.

It was a singular scene. Frank McAlister,

who did not know Armitage by sight,

and did not at all suspect danger to himself,

towered calmly like a colossal statue, his

grave blue eyes just glancing at this menacing

apparition, and then turning a look

of inquiry upon Beaumont. The white-haired

Kershaw, nearly as tall as Frank,

was gazing blandly into the face of the

young man, unconscious that anything

strange was happening, his whole air full

of benignity and satisfaction. Beaumont,

the only one of the three who both saw and

recognized the intruder, had turned squarely

to face him, eyes flaming, eyebrows bristling,

and hands clenched. It must be

remembered that he hated Armitage as a

man who had filled Nellie's life with wretchedness.

At the first glimpse of his insolent

approach and air of menace he had been

filled with such rage, that if he had had a

pistol he would perhaps have shot him instantly.

In a certain sense he would have

been pardonable for such action, for he supposed

that the drunkard's charge was directed

against himself. There he stood, undismayed

and savage; all the more defiant,

because the odds were against him; all the

grimmer because he was unarmed, gouty,

and in no case for battle; as heroic an old

Tartar as ever scowled in the face of death.

When the reeling desperado was within six

feet of him he thundered out, “You scoundrel!”

Armitage made no answer to Beaumont,

and merely stared at him with an indescribably

stupid leer, not unlike the stolid, savage

grin of an angry baboon. Then, lurching

a little to one side, he passed him and

pushed straight towards Frank, at the same

time drawing his revolver. Halting with

face of the young giant, and demanded in

a sort of yell, “What y' here for?”

“I don't understand you, sir,” replied

Frank. “I don't know you.”

“What does this mean?” exclaimed

Beaumont, suddenly realizing that his

guest's life was threatened, and trying to

step between him and Armitage.

“Let me alone,” screamed the drunkard.

“He 's run away with my wife.”

The coarse suspicion thus flung upon

Nellie inflamed her father to fury. Without

a word he seized his son-in-law, pushed

him toward the low steps which led down

from the varanda, and sent him rolling

upon the gravelled walk at their base.

Frank had no weapons. He had come

unarmed into the house of the hereditary

enemies of his house. He had resolved to

put it beyond his power to do battle, even

in self-defence, under the roof of Kate's

father. But he now stepped forward hastily,

calling, “This is my affair, Mr. Beaumont.”

Kershaw stopped him, placing both hands

on his arms, and saying, “You are our

guest. I do not understand this quarrel.

But we are responsible for your safety.”

At the same moment Beaumont hastened

to the door and shouted, “Tom! Vincent!

Nellie! Here, somebody! Bring me my

pistols!”

Then he turned to look, for a shot had

been fired. The overthrown maniac, even

while struggling to rise, had discharged one

barrel of his revolver, aiming, however, as a

drunken man would naturally aim, and

missing his mark. Kershaw let go of Frank,

stepped a little aside and sat down in a

rustic chair, as if overcome by the excitement

of the scene, or by the weakness of

age. Thus freed for action, the youngster

plunged towards his unknown and incomprehensible

enemy, with the intention of

disarming him. Two more shots missed

him, and then there was a struggle. Of

course it was brief; the inebriate went

down almost instantly; his pistol was

wrenched out of his hand and flung away;

then a heavy knee was on his breast and a

hard fist in his neckcloth.

At this moment the younger Beaumonts,

aroused by the firing and by the call of

their father, swarmed out upon the veranda,

every one with his cocked pistol. Seeing

their brother-in-law (of whose domestic misconduct

they knew nothing) under the hostile

hands of a McAlister, they naturally

inferred that here was a fresh outbreak of

the feud, and rushed forward to rescue

their relative.

“Stop, gentlemen,” called Kershaw, but

he was not heard.

“Boys! boys!” shouted Beaumont, limp

ing after them down the steps. “You don't

understand it, boys.”

All might have been explained, and further

trouble avoided, but at this moment

there arrived a rescue for Frank, a rescue

which comprehended nothing, and so did

harm. It seems that Bruce and Wallace

McAlister, learning from their mother what

mission their brother had gone upon, and

having little confidence in the sense or

temper or good faith of their ancient foes,

had decided to mount and follow up the adventure.

When Armitage's first pistol-shot

resounded, they were in ambush behind a

grove not three hundred yards distant. A

few seconds more saw them dashing up to

the gate which fronted the veranda, and

blazing away with their revolvers at the

Beaumonts, who were hurrying towards

Frank. A sharp exclamation from Tom

told that one bullet had taken effect.

“Come here, brother!” shouted Wallace.

“Run for your horse.”

Frank sprang to his feet and stared about

him in bewilderment. He saw Tom handling

his wounded arm; he saw Vincent and

Poinsett aiming towards the road; turning

his head, he saw Bruce and Wallace, also

aiming. It was the feud once more; the

two families were slaughtering each other;

all hope of peace was perishing in blood.

At the top of his speed he ran towards his

brothers, calling, “You are mistaken. Stop,

stop!”

Vincent fired after him. Poinsett, pacific

as he was, discharged several barrels, but

rather at the men on horseback than at

Frank. Tom picked up his pistol with his

sound arm and joined in the skirmish. The

two McAlisters in the highway, sitting

calmly on their plunging horses, returned

bullet for bullet. At least thirty shots were

exchanged in as many seconds. That amateur

of ferocities, chivalrous old General

Johnson, ought to have been there to cure

his sore eyes with the spectacle. Never before

had there been such a general battle

between the rival families as was this hasty,

unforeseen, unpremeditated combat, the

result of a misunderstanding growing naturally

out of lifelong hostility. Peyton Beaumont

alone, knowing that the mêlée was one

huge blunder, took no part in it, and indeed

tried hard to stop it, calling, “Gentlemen,

gentlemen! Hear me one instant.”

When Frank reached his brothers there

was a streak of blood down his cheek from

a pistol-shot scratch across his temple.

Moreover, he was in peril of further harm,

for Randolph Armitage had regained his

feet, and followed him, and was now reeling

through the gate with a drawn bowie-knife.

“For God's sake, stop!” implored

Frank, unaware both of his wound and

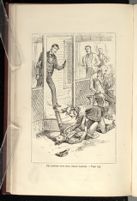

The inebriate went down almost instantly.—Page 133.

[Description: 456EAF. Image of two men fighting outside of a saloon. There are men milling in the background watching, as one man sits dejectedly on a horse post. The fighting men are on the ground, with the upper man holding the arms of the other.]

who attacked me. It was some drunken

brute!”

Wallace made no reply except to spur

past his brother upon the pursuing Armitage

and knock him senseless with a pistolbut

blow over the head.

“Mount your horse,” shouted Bruce.

“They are reloading. Mount your horse.”

“I must go and explain,” cried Frank,

turning back. “I forbid you to fire,” he

added in a terrible voice. “Don't you see

her?”

His dilated eyes were fixed upon Kate

Beanmont, who, with the aid of a negro,

was leading Kershaw into the house. When

she had disappeared and he believed that

she was in safety, he lifted his clasped

hands toward heaven, and reeled as if he

would have fallen.

“Come, Frank,” begged Wallace, throwing

his broken pistol at him in his desperation.

“Do you want us all shot here?

Mount your horse.”

In his confusion and anguish of soul, just

understanding that his brothers would not

leave him, and that he must ride with them

to save their lives, the young man sprang

into his saddle and galloped away.

“I ought to go back,” he said, after he

had traversed a few rods. “I must know

if anything has happened to them.”

“This is the second time that you have

barely escaped being assassinated by those

savages,” replied Bruce, sternly. “If you

are not a maniac, you will come with us.”

“O, it was a horrible mistake,” groaned

Frank. “You meant well, but you were

mistaken. The Beaumonts did not attack

me. It was that madman.”

“That was Randolph Arnitage,” said

Wallace. “Do you mean the fellow that I

knocked down? That was Peyt Beaumont's

son-in-law. He is another of the

murdering tribe. They are all of a piece.”

Perplexed as well as wretched, Frank

made no reply, and dashed on after his

brothers. The retreat was a rapid one,

although two of the horses were wounded,

and Bruce had received a shot in the thigh

which made riding painful. As there was

now only one pistol among the McAlisters,

and as their enemies were well armed and

had fast steeds within easy call, it was well

to distance pursuit.

But the Beaumonts did not think of giving

chase; they were paralyzed by the

shock of an immense calamity.

At the firing of the first shot Kate was

sitting by a window of her own bedroom,

looking out upon the yard through a loop

in the curtain. We may guess that her

object was to get an unobserved glance at

Frank McAlister when he should remount

his horse and ride away. She had so much

confidence in her grandfather's influence,

that she did not expect serious trouble.

The explosion of the pistol surprised her

into a violent fright. To her imagination

the feud was always at hand; it was a

prophet of evil uttering incessant menaces;

it was an assassin ever ready for slaughter.

Her instantaneous thought was that the old

quarrel had broken out in a deadly combat

between her pugnacious brothers and the

man of whom she knew full well at the moment

she loved him. She could not see the

veranda from her window, and she hurried

down stairs into the front-entry hall. There

she heard her father's voice calling for pistols,

and beheld her sister running one way

and her brothers another. In her palpitating

anxiety to learn all that this turmoil meant

she stepped into the veranda, and there

discovered Frank McAlister holding down

Randolph Armitage. Next she heard a

faint voice, — a voice familiar to her and

yet somehow strange, — saying earnestly,

“My dear, go in; you will be hurt.”

Turning her head, she beheld her grandfather

in the rustic chair, motioning her

back. Had she looked at him closely, she

would have perceived that he was very

pale, and that he had the air of a man

grievously ill or injured. But she was in

no condition to see clearly; the hurry and

fright of the occasion made everything

vague to her; she recognized outlines and

little more. Accustomed to obey her venerable

relative's slightest wish, she sprang

into the house and shielded herself behind a

doorpost. Then came the sally of her

brothers; then the trampling of horses

arriving at full speed, and the calling of

strange voices from the road; then a cracking

of pistol-shots, a hissing of bullets, and

a shouting of combatants. She was in an

agony of terror, or rather of anxiety, believing

that all those men out there were being

killed, and screaming convulsively in response

to the discharges. Without knowing

it, she was struggling to get into the

veranda; and without knowing it, she was

being held back by her sister.

Next followed a lull. Nellie leaped

through the doorway, and Kate at once

leaped after her. There were her father

and her brothers; they were staring after

Frank McAlister and his brothers; these

last were already turning away. She did

not see Tom's bleeding arm, nor the prostrate

Randolph Armitage. Her impression

was that every one had escaped harm, and

she uttered a shriek of hysterical joy.

But when she turned to look for her

grandfather, she was paralyzed with horror.

His face was of a dusky or ashy pallor, and

he seemed to be sinking from his seat. For

a moment she could not go to him; she

stood staring at him with outstretched arms;

dilated eyes. Then seeing black Cato step

out of a window and approach the old man

with an air of alarm, she also ran forward

and threw herself on her knees before him,

with the simple cry of “O grandpapa!”

He was so faint with the shock of his

wound and the loss of blood, that he could

not answer her and probably could not see

her. He sat there inert and apparently

unconscious, his grand old head drooping

upon his chest, and his long silver hair falling

around his face.

Of a sudden Kate, who had been on the

point of fainting, was endowed with immense

strength. Aided only by the negro

boy, who trembled and whimpered, “O

Mars Kershaw! Mars Kershaw!” she lifted

the ponderous frame of her grandfather, and

led him reeling into the house.

| CHAPTER XXXI. Kate Beaumont | ||