Kate Beaumont with illustrations |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. | CHAPTER XII. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. |

| 30. |

| 31. |

| 32. |

| 33. |

| 35. |

| 36. |

| 37. |

| 38. |

| 39. |

| CHAPTER XII. Kate Beaumont | ||

12. CHAPTER XII.

We shall know in due time what success

Kate had in pleading with Vincent to withdraw

his challenge.

While the girl, aided by her grandfather,

was resisting the demon of duels in the

Beaumont house, Mr. Frank McAlister was

maintaining an equally dubious contest with

the same monster under his paternal roof-tree.

We must hurry over the scene of his arrival

at home. There had been a pleasant

family drama; there had been warm welcome

for the returned wanderer. The deliberate

and solemn Judge was not the kind

of man to fly into a spasm of emotion, like

his excitable enemy, Peyt Beaumont; but

he had a calm sufficiency of the true parental

stuff in him, and he was proud of his

gigantic, handsome son, full of all the wisdom

of the East; he gave him a vigorous

hand-shaking, and looked for an instant

like kissing him. Mrs. McAlister, a tall,

pale, gray, mild, loving woman, took the

Titan to her arms as if he were still an infant.

Mary worshipped him, as girls are

apt to worship older brothers, at least when

they are big and handsome. Bruce, the

eldest son, was all that a South Carolina

gentleman should be on such an occasion.

Wallace at once gloried in Frank's grandeur

and beauty, and wilted wofully under a

sense of his own inferiority.

The story of the shipwreck was told to

affectionately breathless listeners; and then

came, almost by necessity, the saving of Miss

Beaumont from a watery grave.

“I have some hope,” added Frank, with

the blush of a man who feels far more than

he says, “that the incident may pave the

way to a reconciliation of the families.”

“Heaven grant it!” murmured Mrs. McAlister,

her face illuminated with hope of

peace and perhaps with foresight of love

and marriage.

“Amen!” responded the Judge in a perfunctory,

head-of-the-family, not to say beadle-like,

manner. One of those model men

who set an example, you know; one of

those saints who keep up appearances, even

at home.

“By George, it ought to,” muttered Wally,

conscience-stricken about his duel. “It

ought to bring about a reconciliation. But,

by George, there 's no telling.”

Then, at a proper moment, when only the

of the quarrel with Vincent. It must be

understood that among the McAlisters duels

were not such common property, such subjects

of genial family conversation, as among

the Beaumonts. The McAlisters fought as

promptly as their rivals; but, Scotch-like

and Puritan-like, they treated fighting as a

matter not to be bragged of and gossiped

about; they drew a decorous veil over their

occasional excesses in the way of homicide.

When a McAlister boy got into an unpleasantness,

he never mentioned it to father,

mother, or sister, not even after the shots

had been exchanged. The Judge believed

that duelling was sometimes necessary; but

he did not want to have the air of encouraging

it: first, because he was a father and

cared for his sons' lives; second, because

he had a certain character to maintain in

the district. Mrs. McAlister, a religious

and tender-hearted woman, looked upon the

code of honor with steady horror. Mary

tormented her brothers by crying over their

perils, even when those perils had passed

and were become glories.

We can imagine Frank's disgust and grief

when he learned that there was to be another

Beaumont and McAlister duel. He

pleaded against it; he inveighed against it;

he sermonized against it.

“Frank, you make me think of converted

cannibals coming home to preach to their

tribe,” said Wallace, smiling amiably, but

unmoved and unconvinced.

“Who is your second?” asked Frank,

hoping to find more wisdom in that assistant

than in the principal.

“Bruce,” replied Wallace with a queer

grimace, somewhat in the way of an apology.

“Bruce! Your own brother?” exclaimed

the confounded Frank. “Why, that is horrible.

And is n't it something unheard of?

It strikes me as an awful scandal.”

“It is unusual,” admitted Wallace. “But

Vincent Beaumont makes no objection to it,

and, moreover, he has chosen his own connection,

Bent Armitage. Besides,” he added,

looking at his elder brother with an almost

touching confidence, “Bruce will fight me

better than any other man could.”

Bruce McAlister was a man of about six

feet, too slender and too lean to be handsome

in a gladiatorial sense, but singularly

graceful. Although not much above thirty,

his face was haggard and marked by an air

of lassitude. He was a consumptive. Perhaps

the disease had increased the charm of

his expression. His large hazel eyes, sunk

as they were in sombre hollows, had a melancholy

tenderness which was almost more

than human. His face was so gentle, so refined,

so gracious, that it charmed at first

sight. There was no resisting the sweet

smile, the flattering bow and petting address

of this man. He put strangers at ease in

an instant; he made them feel with a look

that they were his valued friends; he so

impressed them in a minute that they never

forgot him in all their lives. It would not

be easy to find another man who had such

an appearance of thinking altogether of others

and not at all of himself.

“It is an unusual step, Frank,” said

Bruce, in a mellow, deep, and yet weak

voice. “It was of course not ventured upon

without the full consent of the other party.

I accepted the position solely with the hope

of diminishing Wallace's danger.”

“Well!” assented Frank with a groan.

“And now, Bruce, tell me the whole thing.

What is the exact value of the provocation?”

In a quiet tone and without a sign of indignation

Bruce related the story of the

difficulty.

“Beaumont's manner and words were

irritatingly sarcastic,” he concluded. “Wallace

naturally resented it.”

“Still, all that he said was — was parliamentary,”

urged Frank. “Wallace, I don't

want to judge you; but it does seem to me

that you might have spared your reply; it

was terribly severe. Could n't you apologize?

If I were in your place, I would. I

would, indeed.”

Wallace stared, rubbed his head meditatively,

and then shook it decidedly.

“And for this you mean to fight?” pursued

Frank. “Actually mean to draw a

pistol on your fellow-man? The whole

thing — I mean the code duello — is a barbarity.

I was brought up to reverence it.

From this time I abjure it.”

“Fight? Well, yes,” returned Wallace,

again rubbing his prematurely bald crown;

not quite bald, either; simply downy. “Of

course I will fight. Not that I admire

fighting. It 's the reasoning of beasts, sir.

And as for the duello, well, I look on it as

you do; I consider it out of date, barbarous.

But society — our society, I mean — demands

it. If society says a gentleman must

— noblesse oblige — why, that settles it. If

it says a gentleman should wear a beaver,”

lifting his hat and gesturing with it, “why,

he must get one. Disagreeable thing; ugly

and uncomfortable; just look at it. Look

at my head, too. Bald at twenty-eight!

That 's the work of a black, hot beaver.

But since it 's the distinguishing topknot of

a gentleman, I submit to it. Just so with

the duello. I think it 's blasted nonsense,

and yet I can't ignore it. As for the Beaumonts,

I don't want to be shooting at Beaumonts.

Just as willing to let them alone as

to let anybody else alone. But when a

Beaumont ruffles me, and society says, `Let 's

see how he takes it,' why I take it with pistols.

Very sorry to do it, but don't see how I

one. Logic don't support it, and God won't

approve it. Know all that. Not going to

fool myself with trying to prove that I don't

know it. And, by George, I wish I could

make my reason and practice agree. Wish

I could, and know I can't.”

“Would you mind leaving this matter to

our elders?” asked Frank, the idea of a

family council occurring to him as it had occurred

to Colonel Kershaw.

“O Lord! don't!” begged Wallace.

“You could n't beat me out of it, but you 'd

bother me awfully. You 'd have mother on

your side, sure, and she 's an army. Yes,

by George, she 's one of those armies that

are marshalled by the Lord of hosts,” declared

Wallace, stopping to meditate upon

the perfections of his mother. “She is a

peacemaker,” he resumed. “I 've heard her

say that she almost regretted having a boy;

if her children were only all girls, this feud

might have died out. By George, I would

n't mind being one of the girls. I might

have been handsomer. I might have kept

my hair, too; not being obliged to wear a

beaver.” Here he rubbed the “fuzzy”

summit of his head with rueful humor.

“By heavens! bald at twenty-eight! It 's

an ugly defect.”

He was so cheerful and resolute, notwithstanding

the shadow of death which lay

across his to-morrow, that Frank was in

despair.

At this hopeless stage of the conversation

a negro brought in word that “Mars

Bent Armitage wanted to see Mars Bruce.”

Bruce went to another room, received

Armitage with an almost affectionate courtesy,

talked with him for a few moments in a

low tone, and waited on him to his horse as

tenderly as if he were a lady. When he

returned to his two brothers there was in

his usually melancholy eyes something like

a smile of pleasure.

“I am the bearer of remarkable news,”

he said calmly. “The duel can now be

honorably avoided.”

“How?” demanded the eager Frank.

“What!” exclaimed the astonished Wallace.

“Hear this,” continued Bruce, opening a

letter. “`On behalf of my principal, Mr.

Vincent Beaumont, I withdraw the challenge

sent to Mr Wallace McAlister. The

sole motive of this withdrawal is the sense

of obligation on the part of Mr. Beaumont

and his family toward Mr. Frank McAlister

for saving the life of Miss Catherine Beaumont.'

Signed, Bentley Armitage.”

“By George!” exclaimed Wallace, and

continued to say by George for a considerable

time. “I owe him an apology,” he presently

broke out. “If I don't owe him one,

I 'll give him one. Bruce, write me an

apology, won't you? By heavens, I never

thought a Beaumont could be so human.

Anything, Bruce; I 'll sign anything. This

is new times, something like the millennium.

What would our ancestors say? Frank, by

George, this is your work, and it 's a big

job. In saving the girl's life you have

saved mine, perhaps, and Vincent's. Three

lives at one haul! How like the Devil — I

mean how like an angel — you do come

down on us! By George, old fellow, I 'm

amazingly obliged to you. I am, indeed.

Is that thing ready, Bruce? Let 's have it.

There! Now, Bruce, if you 'll be kind

enough to transmit that in your very best

manner — By the way, old fellow, I 'm very

much obliged to you for standing by me.

I 'm devilish lucky in brothers.”

“I do hope that this is the beginning of

the ending of the family feud,” was the

next thing heard from Frank.

“Well, I don't mind,” agreed Wallace.

“You ought to say more than that,”

urged Frank. “One friendly step deserves

another. You have been fairly beaten so

far in the race of humanity by this Beaumont.”

“Yes, he has got the lead,” conceded

Wallace. “For once I knock under to a

Beaumont. The fact confounds me; it fairly

takes the breath out of me. But will he

last? Can the blasted catamounts become

friendly?”

“Try them,” said Frank. “I propose a

call on them.”

“Wallace has apologized,” observed

Bruce. “The next advance should come

from the Beaumont side.”

“We ought to give more than we receive,”

lectured Frank. “It is the part of true

gentlemen, as the word is understood in our

times, or should be understood.”

“It is worth considering,” admitted Bruce;

“it is worth while to suggest the idea to our

father.”

“And mother,” was Frank's energetic

amendment, to which Bruce did not think

it best to reply. The honor of the family

was very dear to him, and he did not believe

that women were qualified to judge

its demands, much as he respected the

special good sense of his mother.

Back to the Beaumonts one must now

hasten, to learn how they received the

apology. Vincent glanced through Wallace's

letter without changing expression, nodded

as a man nods over a compromise which is

only half satisfactory, read it aloud to his

father and brothers (with a sister listening

in the next room), and then filed it away

among his valuable papers, all without a

word of comment. Beaumont senior was

gratified, and then suddenly enraged, and

then gratified again, and so on.

“Why, Kershaw, the fellow has some

streaks of gentility in him,” he admitted,

with a smile of wonder and satisfaction,

walking up and down with the pacific,

manageable air of a kindly, led horse. But

presently he gave a start and a glare, like a

tiger who hears hunters, and broke out in a

snarl: “Why the deuce did n't he say all

this at first? He ought to have apologized

at once. The scoundrel!!”

After some further thought, he added in a

mild growl: “Well, it might have been

worse. After all, the blockhead has made

it clear that he does n't mean to take advantage

of Vincent's magnanimity. Yes,

magnanimity!” he trumpeted, looking about

for somebody to dispute it. “By heavens,

Vincent, you have been as magnanimous as

a duke, by heavens!”

Here the magician who had wrought

thus much of peace into the woof of hate

came smiling and glowing into the room,

slipped her arm through that of her eldest

brother, and whispered: “So it has ended

well, Vincent. I am so much obliged to

you! I am so happy!”

Next she glided over to her father and

possessed herself of his hairy hand, saying,

“Come, your man-business has gone all

right; come and show me where to put my

flower-beds.”

She was bent, — the audacious young

thing, it seemed incredible when you looked

at her sweet, girlish face, — but she was

bent upon taming these fine, fighting panthers;

and she was bringing to bear upon

the work a beautiful combination of tenderness,

of patient management and gentle

imperiousness; she was inspired to attempt

a labor far beyond her years. The trying

circumstances which surrounded her had

matured her with miraculous rapidity, and

brought into bloom at once all her nobler

moral and stronger mental qualities. She

was like those youthful generals who have

performed prodigies because they were

called upon to perform prodigies, and did

not yet know that prodigies were humanly

impossible. No doubt it was well for the

girl that Heaven had given her so much

beauty and such an imposingly sweet expression

of dignity and purity. A plainer

daughter and sister, no matter how good

and wise and resolute, might not have accomplished

such wonders.

We will not follow her and her father

into the garden; we will simply say that

her flower-beds bore great fruit, and that

shortly.

For on the following day two horsemen

left the mansion of the Beaumonts and rode

towards the mansion of the McAlisters.

They rode mainly at a walk, the reason

being that one of them was over eighty

years old, while the other, although not

above fifty-five, was shaky with pains and

diseases. Several times during the transit

of four miles the younger suddenly checked

his horse and turned his nose homeward,

saying, “By heavens, I can't do it, Kershaw.

No, by heavens!”

“Come on, my dear Beaumont,” mildly

begged the venerable Colonel. “You will

never regret it. It is the noblest chance

you ever had to be magnanimous.”

“Do you think so, Kershaw? Well,

magnanimity is a gentlemanly thing. By

heavens, that was a devilish fine thing that

Vincent did. It put a feather in his cap as

high as the plume of the Prince of Wales.

Moral courage and dignity! By heavens,

I am proud of the boy.”

“So am I,” said Kershaw.

“Are you?” grinned the delighted Beaumont.

“By heavens, I 'm delighted to hear

you say so. I was afraid you did n't appreciate

Vincent. But I ought to have known

better; every gentleman would appreciate

him. The man who now does n't appreciate

Vincent, he 's — he 's an ass and a

scoundrel,” declared Beaumont, beginning

to tremble with rage at the thought of encountering

and chastising such a miscreant.

“Well, Kershaw,” he added, “let us go

on.”

After a little he added in a tone of

apology, “Some people might say that this

errand is the business of a younger man.

But my sons are not related to Kate as you

and I are. The girl springs directly from

your veins and mine; and consequently we

are the proper persons to thank the man

who saved her life. Don't you think so,

Kershaw?”

“Certainly,” replied the patient Colonel,

who had already advocated that view with

all his eloquence.

Presently they discovered the McAlister

house, and here Beaumont came to another

halt. This time his resistance was more

obstinate than before; it was like the struggle

of an ox when he smells the blood of

the slaughter-block.

“Kershaw, I can't go to that house,”

he said, his face and air full of tragic dignity.

“That house is the abode of the

enemies of my race. There is a man in

that house who has my brother's blood on

his hands. I can't go there; no, Kershaw,

by God!”

His voice trembled; it was full of anguish

and anger; it was a groan and a menace.

The Colonel made no remonstrance and

no spoken reply. He took off his hat and

bared his long white hair to the sun, as if in

respect to Beaumont's emotion. In this

attitude he waited silently for the storm of

feeling to rage itself out.

“My father never would have entered

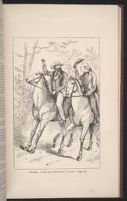

"Kershaw, I can't go to that house," he said.—Page 52.

[Description: 456EAF. Image of two men riding horses along a tree-lined path. One man is doffing his hat, while the other is raising a clenched fist in horror.]

McAlister ever crossed my threshold. There

has been nothing but hate and blood between

us. It has always been so, and it must

always be so. I am too old to learn new

ways.”

Still the Colonel sat silent and uncovered,

with his long silver hair shining under the

hot sun. The sight of this humility and

patience seemed to trouble Beaumont.

“You can't feel as I do, Kershaw,” he

said. “Of course you can't.”

“Let us try to make the future unlike the

past,” returned the Colonel, in a tone which

was like that of prayer.

Beaumont shook his head more in sadness

than in anger.

“This young man, Frank McAlister, has

already begun the work,” continued the

Colonel. “Shall Kate's father and grandfather

foil him?”

Beaumont began to tremble in every

limb; he was weak with his diseases, and

this struggle of emotions was too much for

him; he held on to his saddle-bow to keep

himself from growing dizzy.

“I don't feel that I can do it, Kershaw,”

he said, in a voice which had one or two

embryo sobs in it. How, indeed, weakened

as he was by maladies, could he choose between

all the family feelings of his past and

the totally new duty now before him, without

being shaken?

“Beaumont,” was the closing appeal of

the Colonel, “you will, I hope, allow me to

go on alone and return thanks for the life

of my granddaughter.”

“No, by heavens!” exclaimed the father,

turning his back at once on all his bygone

life, its emotions, its beliefs, its acts, and

traditions. “No. If you must go, I go with

you.”

“God bless you, my dear Beaumont!”

said Kershaw, his voice, too, perhaps a little

unsteady.

After some further riding Beaumont

added: “But we will see the boy alone.

Not the Judge. I won't see the Judge.

If I meet that old fox, I shall quarrel with

him. I can't stand a fox when he 's as

big as an elephant and as savage as a

hyena.”

A little later he asked: “You 're sure

Lawson thinks well of this step?”

“He approves of it thoroughly,” declared

the Colonel. “He considers it the only

thing we can do, since the apology has been

made.”

“Well, Lawson ought to know what 's

gentlemanly,” said Beaumont. “Lawson

has always been a habitué of our society.

By heavens! if Lawson does n't know what 's

gentlemanly, he 's an ass.”

And so at last they were at the door of

the McAlister mansion.

| CHAPTER XII. Kate Beaumont | ||