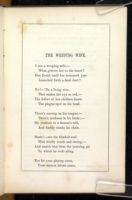

| THE HARWOODS. Water-drops | ||

33. THE HARWOODS.

Can see all the idols of hope depart,

Yet still live on.—and smile, and bless

Man in his utmost wretchedness.”

Procter.

The flood of emigration which beats against the shores

of the United States, seems to have no ebb-tide. From

the ices of the Baltic,—from the dense forests of Germany,—from

the weeping Isle of the shamrock, exhalations

gather, hurrying drops aggregate, streamlets mingle, and

press onward with a rushing sound. The young West,

like some broad sea, receives them, taking no more note

of each than Ocean of its tribute-waters.

Here and there, in the streets of our cities, the tall,

tasseled cap of the Pole, the rainbow plaid of the High-lander,

or the thin smoke curling from the Bavarian

pipe, gleam for a moment, to be dispersed in measureless

distance, or merged in one common mass. The accents

of a strange language may indeed continue to murmur

through a generation or two, but dialects, like the lineaments

of national character, blend, fade, and are forgotten.

Amid this ceaseless influx of foreign material, is also

fluctuation, a fluttering of the integral parts. This elemental

movement and strife, tends ever towards the setting

sun. Yet the West recedes from its followers, like

the horizon from the pursuing child. Time was, and

that within the memory of the living, when to us, the

dwellers in New England, the untrodden wilds of Ohio

were counted as the extreme West. Now, the stately

cities that glitter there, fall short of the central point of

the empire.

Where, then, is the West? On the banks of the father

of waters?—along the pictured rocks of the mighty lake?

—at Illinois?—at Iowa?—at Wisconsin?—Scarcely!

The searchers for the West, like the gold seekers among

the settlers of Virginia, still analyze yellow earth for the

invisible and ideal good;—pausing only amid the arid

sands of Oregon, or on the sounding shores of the

Pacific.

New England, the fountain of these internal supplies,

still vigorously sustains this drain upon her vitality. The

farmer who has many sons,—if the homestead be too

narrow, confidently points out to them a place at the

West. Thither speed the self-denying missionary, with

his Bible, and the persevering teacher with his text-book,

laboring to make the wilderness blossom as the rose.

Perhaps, thither also may turn the briefless lawyer, to

pour his philippics from the stump, and carry the votes

of a whole country by his eloquence. The broken merchant

axe, and making the trees groan, instead of his creditors.

Every over-stocked profession finds there a safety-valve.

Those who are discontented, and in debt, “make to

themselves a captain,” and go forth to a more attractive

abode than the cave of Adullam. Lost wealth takes

heart and looks up, where are none richer than itself;

wasted health fattens and grows strong, with the wild venison,

and the toil that takes it. The strong passion of

wandering becomes satiated and tame, amidst the boundless

prairies; and forfeited reputation, and even flying

guilt, fear no reproach amid Texan vales.

From the trains of baggage wagons peep forth the

faces of young children; and on the canal-boat the careful

matron, while her babe sleeps, plies the knitting-needles,

ever steering in the wake of the westering sunbeam.

Not many years since, where the lofty forests of

Ohio, towering in unshorn majesty, cast a solemn shadow

over the deep verdure of beautiful and ample vales, a

small family of emigrants were seen pursuing their solitary

way. They travelled on foot, but not with the

aspect of mendicants, though care and suffering were

visibly depicted on their countenances. The man walked

first, apparently in no kind or compromising mood. The

woman carried in her arms an infant, and aided the

progress of a feeble boy, who seemed sinking with exhaustion.

An eye accustomed to scan the never-resting

tide of emigration, might discern, that these pilgrims

from some species of adversity, to one of those

imaginary El Dorados, among the shades of the far

West, where it is fabled that the evils of mortality have

found no place.

James Harwood, the leader of that humble group, who

claimed from him the charities of husband and of father,

halted at the report of a musket, and while he entered a

thicket to discover whence it proceeded, the weary and

sad-hearted mother sate down upon the grass. Bitter

were her reflections during that interval of rest among

the wilds of Ohio. The pleasant New England village

from which she had just emigrated, and the peaceful

home of her birth, rose up to her view, where, but a few

years before, she had given her hand to one, whose unkindness

now strewed her path with thorns. By constant

and endearing attentions, he had won her youthful love,

and the two first years of their union promised happiness.

Both were industrious and affectionate, and the smiles of

their infant in his evening sports, or his slumbers, more

than repaid the labors of the day.

But a change became visible. The husband grew inattentive

to his business, and indifferent to his fireside.

He permitted debts to accumulate in spite of the economy

of his wife, and became more and more offended at her

remonstrances. She strove to hide, even from her own

heart, the vice that was gaining the ascendency over

him, and redoubled her exertions to render his home

avail, or contemptuously rejected. The death of her

beloved mother, and the birth of a second infant, convinced

her, that neither in sorrow nor in sickness, could

she expect sympathy from him to whom she had given

her heart, in the simple faith of confiding affection. They

became miserably poor, and the cause was evident to

every observer. In this distress a letter was received

from a brother, who had been for several years a resident

in Ohio, mentioning that he was induced to remove

farther westward, and offering them the use of a tenement

which his family would leave vacant, and a small portion

of cleared land, until they might be able to become purchasers.

Poor Jane listened to this proposal with gratitude.

She thought she saw in it the salvation of her husband.

She believed that if he were divided from his intemperate

companions, he would return to his early habits of industry

and virtue. The trial of leaving native and endeared

scenes, from which she would once have recoiled, seemed

as nothing in comparison with the prospect of his reformation,

and returning happiness. Yet, when all their

few effects were transmuted into the waggon and horse,

which were to convey them to a far land, and the scant

and humble necessaries which were to sustain them on

their way thither;—when she took leave of brother and

sisters, with their households;—when she shook hands

with the friends whom she had loved from her cradle,

when the hills that encircled her native village, faded

into the faint blue outline of the horizon, there came over

her such a desolation of spirit, such a foreboding of evil,

as she had never before experienced. She blamed herself

for these feelings, and repressed their indulgence.

The journey was slow and toilsome. The autumnal

rains, and the state of the roads were against them. The

few utensils and comforts which they carried with them,

were gradually abstracted and sold. The object of this

traffic could not be doubted:—the effect was but too

visible in his conduct. She reasoned,—she endeavored

to persuade him to a different course. But anger was

the only result. Even when he was not too far stupefied

to comprehend her remarks, his deportment was exceedingly

overbearing and arbitrary. He felt that she had

no friends to protect her from insolence, and was entirely

in his own power; while she was compelled to realize

that it was a power without generosity, and that there

is no tyranny so perfect as that of a capricious and

alienated husband.

As they approached the close of their distressing journey,

the roads became worse, and their horse utterly

failed. He had been scantily provided for, as the intemperance

of his owner had taxed and impoverished everything,

for its own vile indulgence. Jane wept as she

looked upon the dying animal, and remembered his

faithful and ill-requited services.

The unfeeling exclamation with which her husband

abandoned him to his fate, fell painfully upon her heart,

adding another proof of the extinction of his sensibilities,

in the loss of that pitying kindness for the animal creation,

which exercises a silent and salutary guardianship

over our higher and better sympathies. They were now

approaching within a short distance of the termination

of their journey, and their directions had been very clear

and precise. But his mind became so bewildered, and

his heart so perverse, that he persisted in choosing bypaths

of underwood and tangled weeds, under the pretence

of seeking a shorter route. This increased and

prolonged their fatigue, but no entreaty of his wearied

wife was regarded. Indeed, so exasperated was he at

her expostulations, that she sought safety in silence. The

little boy of four years old, whose constitution had been

feeble from his infancy, became so feverish and distressed,

as to be unable to proceed. The mother, after in vain

soliciting aid and compassion from her husband, took him

in her arms, while the youngest, whom she had previously

carried, and who was unable to walk, clung to her

shoulders. Thus burdened, her progress was slow and

painful. Still, she was enabled to hold on; for the

strength that nerves a mother, toiling for her sick child,

is from God. She even endeavored to press on more

rapidly than usual, fearing, that if she fell behind, her

husband would tear the sufferer from her arms, in some

paroxysm of his savage intemperance.

Their road during the day, though approaching the

small settlement where they were to reside, lay through

a solitary part of the country. The children were faint

and hungry; and as the exhausted mother rested upon

the grass, trying to nurse her infant, she drew from her

bosom the last piece of bread, and held it to the

parched lips of the feeble child. But he turned away

his head, and with a scarcely audible moan, asked for

water. Feelingly might she sympathize in the distress

of the poor outcast from the tent of Abraham, who laid

her perishing son among the shrubs, and sat down a good

way off, saying, “Let me not see the death of the child.”

But this Christian mother was not in the desert, nor in

despair. She looked upward to Him, who is the Refuge

of the forsaken, and the Comforter of those whose spirits

are cast down.

The sun was drawing towards the west, as the voice of

James Harwood was heard, issuing from the forest, attended

by another man with a gun, and some birds at his

girdle.

“Wife, will you get up now, and come along? we are

not a mile from home. Here is John Williams, who went

from our part of the country, and says he is our next-door

neighbor.”

Jane received his hearty welcome with a thankful

spirit, and rose to accompany them. The kind neighbor

took the sick boy in his arms, saying,—

“Harwood, here, take the baby from your wife. We

do not let our women bear all the burdens, in Ohio.”

James was ashamed to refuse, and reached his hands

towards the child. But accustomed to his neglect, or

unkindness, it hid its face, crying, in the maternal bosom.

“You see how it is; she makes the children so cross

that I never have any comfort of them. She chooses to

carry them herself, and always will have her own way

in everything.”

“You have come to a new-settled country, friends,”

said John Williams, “but it is a good country to get a

living in. The crops of corn and wheat are such as you

never saw in New England. Our cattle live in clover,

and the cows give us cream instead of milk. There is

plenty of game to employ our leisure, and venison and

wild turkey do not come amiss now and then, on a farmer's

table. Here is a short cut I can show you, though

there is a fence or two to climb. James Harwood, I shall

like well to talk with you about old times, and old friends

down East. But why don't you help your wife over the

fence with her baby?”

“So I would, but she is so sulky. She has not spoken

a word to me all day. I always say, let such folks take

care of themselves, till their mad fit is over.”

A cluster of log-cabins now met their view through an

opening in the forest. They were pleasantly situated in

the midst of an area of cultivated lands. A fine river,

surmounted by a rustic bridge, formed of the trunks of

autumnal verdure.

“Here we live,” said their guide, “a hard-working,

contented people. That is your house, which has no

smoke curling up from the chimney. It may not be quite

so genteel as some you have left behind in the old States,

but it is about as good as any in the neighborhood. I'll

go and call my wife to welcome you. Right glad will

she be to see you, for she sets great store by folks from

New England.”

The inside of a log-cabin, to those not habituated to it,

presents but a cheerless aspect. The eye needs time to

accustom itself to the rude walls and floors, the absence

of glass windows, and doors loosely hung upon leather

hinges. The exhausted woman entered, and sank down

with her babe. There was no chair to receive her. In

the corner of the room stood a rough board table, and a

low frame resembling a bedstead. Other furniture there

was none. Glad, kind voices of her own sex, recalled her

from her stupor. Three or four matrons, and several blooming

young faces, welcomed her with smiles. The warmth

of reception in a new colony, and the substantial services

by which it is manifested, put to shame the ceremonious

and heartless professions, which, in a more artificial state

of society, are sometimes dignified with the name of

friendship.

As if by magic, what had seemed almost a prison,

assumed a different aspect, under the ministry of active

fireplace; several chairs, and a bench for the children appeared;

a bed, with comfortable coverings, concealed the

shapelessness of the bedstead, and viands to which they

had long been strangers, were heaped upon the board.

An old lady held the sick boy tenderly in her arms,

who seemed to revive, as he saw his mother's face brighten;

and the infant, after a draught of fresh milk, fell

into a sweet and profound slumber. One by one, the

neighbors departed, that the wearied ones might have an

opportunity of repose. John Williams, who was the last

to bid good-night, lingered a moment ere he closed the

door, and said,—

“Friend Harwood, here is a fine, gentle cow, feeding

at your door; and for old acquaintance sake, you and

your family are welcome to the use of her for the present,

or until you can make out better.”

When they were left alone, Jane poured out her gratitude

to her Almighty Protector, in a flood of joyful

tears. Kindness, to which she had recently been a

stranger, fell as balm of Gilead upon her wounded

spirit.

“Husband,” she exclaimed in the fulness of her heart,

“we may yet be happy.”

He answered not, and she perceived that he heard not.

He had thrown himself upon the bed, and in a sleep of

stupefaction, was dispelling the fumes of inebriety.

This new family of emigrants, though in the deepest

they had long been strangers. The difficulty of procuring

ardent spirits in the small and isolated community,

promised to be the means of establishing their peace.

The mother busied herself in making their humble tenement

neat and comfortable, while her husband, as if

ambitious to earn in a new residence, the reputation he

had forfeited in the old, labored diligently to assist his

neighbors in gathering their harvest, receiving in payment

such articles as were needed for the subsistence of

his household. Jane continually gave thanks in her

prayers for this great blessing; and the hope she permitted

herself to indulge of his permanent reformation,

imparted unwonted cheerfulness to her brow and demeanor.

The invalid boy seemed to gather healing from

his mother's smiles; for so great was her power over

him since sickness had rendered his dependence complete,

that his comfort, and even his countenance, were a faithful

reflection of her own. Perceiving the degree of her

influence, she endeavored to use it, as every religious

parent should, for his spiritual benefit. She supplicated

that the pencil which was to write upon his soul, might

be guided from above. She spoke to him in the tenderest

manner of his Father in Heaven, and of His will

respecting little children. She pointed out His goodness

in the daily gifts that sustain life, in the glorious sun as

he came forth rejoicing in the east, in the gently-falling

rain, the frail plant, and the dews that nourish it. She

even the storm, and the mighty thunder, because they

came from God. She repeated to him passages of

Scripture with which her memory was stored; and sang

hymns until she perceived that, if he was in pain, he

complained not, if he might but hear her voice. She

made him acquainted with the life of the blessed Redeemer,

and how he called young children to his arms,

though the disciples forbade them. And it seemed as if

a voice from Heaven urged her never to desist from

cherishing this tender and deep-rooted piety;—because

like the flower of grass he must soon pass away. Yet

though it was evident that the seeds of disease were in

his system, his health at intervals seemed to be improving;

and the little household partook, for a time, the

blessings of tranquillity and contentment.

But let none flatter himself, that the dominion of vice

is suddenly, or easily broken. It may seem to relax its

grasp, and to slumber,—but the victim who has long

worn its chain, if he would utterly escape, and triumph

at last, must do so in the strength of Omnipotence.

This, James Harwood never sought. He had begun to

experience that prostration of spirits which attends the

abstraction of an habitual stimulant. His resolution to

recover his lost character, was not proof against this

physical inconvenience. He determined at all hazards to

gratify his depraved appetite. He laid his plans deliberately,

and with the pretext of making some arrangements

the road, departed from his home. His stay was protracted

beyond the appointed limit, and at his return, his

sin was written on his brow, in characters too strong to

be mistaken. That he had also brought with him some

hoard of intoxicating liquor, to which to resort, there

remained no room to doubt. Day after day, did his

shrinking household witness the alternations of causeless

anger, and brutal tyranny. To lay waste the comfort of

his wife, seemed his paramount object. By constant

contradiction and misconstruction, he strove to distress

her, and then visited her sensibilities upon her as

sins. Had she been obtuse by nature, or indifferent

to his welfare, she might with greater ease have borne

the cross. But her youth was nurtured in tenderness,

and education had refined her susceptibilities, both of

pleasure and pain. She could not forget the love he had

once manifested for her, nor prevent the chilling contrast

from filling her soul with anguish. She could not resign

the hope, that the being who had early evinced correct

feelings, and noble principles of action, might yet be

won back to that virtue which had rendered him worthy

of her affections. Still, this hope deferred, was sickness

and sorrow to the heart. She found the necessity of

deriving consolation, and the power of endurance, wholly

from above. The tender invitation by the mouth of

a prophet, was balm to her wounded soul,—“As a

woman forsaken and grieved in spirit, and as a wife of

thy God.”

So faithful was she in the discharge of the difficult

duties that devolved upon her,—so careful not to irritate

her husband, by reproach or gloom,—that to a casual

observer, she might have appeared to be confirming the

doctrine of the ancient philosopher, that happiness is in

exact proportion to virtue. Had he asserted, that virtue

is the source of all that happiness which depends upon

ourselves, none could have controverted his position.

But to a woman,—a wife,—a mother, how small is the

portion of independent happiness! She has woven the

tendrils of her soul around many props. Each revolving

year renders their support more necessary. They

cannot waver, or warp, or break, but she must tremble

and bleed.

There was one modification of her husband's persecutions,

which the fullest measure of her piety could not

enable her to bear unmoved. This was unkindness to

her feeble and suffering boy. It was at first commenced

as the surest mode of distressing her. It opened a direct

avenue to her lacerated heart-strings. What began in

perverseness, seemed to end in hatred, as evil habits

often create perverted principles. The wasted and wild-eyed

invalid, shrank from his father's glance and footstep,

as from the approach of a foe. More than once

had he taken him from the little bed, which maternal

the cold of the winter storm.

“I mean to harden him,” said he. “All the neighbors

know that you make such a fool of him, that he will

never be able to get a living. For my part, I wish I had

never been called to the trial of supporting a useless

boy, who pretends to be sick, only that he may be coaxed

by a silly mother.”

On such occasions, it was in vain that the mother

attempted to protect the child. She might neither shelter

him in her bosom, nor control the frantic violence of

the father. Harshness and the agitation of fear, deepened

a disease which might else have yielded. The timid boy,

in terror of his natural protector, withered away like a

blighted flower. It was of no avail that friends remonstrated

with the unfeeling parent, or that hoary-headed

men warned him solemnly of his sins. Intemperance

had destroyed his respect for man, and his fear of God.

Spring, at length, emerged from the shades of that

heavy and bitter winter. But its smile brought no gladness

to the declining child. Consumption fed upon his

vitals, and his nights were restless, and full of pain.

“Mother, I wish I could smell the violets that grew

upon the green bank by our dear old home.”

“It is too early for violets, my child. But the grass

is beautifully green around us, and the birds sing sweetly,

as if their hearts were full of praise.”

“In my dreams last night, I saw the clear waters of

I wish I could taste them once more. And I heard such

music too, as used to come from that white church among

the trees, where every Sunday, the happy people meet

to worship God.”

The mother knew that the hectic fever had been long

increasing, and now detected such an unearthly brightness

in his eye, that she feared his intellect wandered.

She seated herself on his low bed, and bent over him.

He lay silent for some time.

“Do you think my father will come?”

Dreading the agonizing agitation, which in his paroxysms

of coughing and pain, he evinced at the sound of

his father's well-known step, she answered,—

“I think not, love. You had better try to sleep.”

“Mother I wish he would come. I do not feel afraid

now. Perhaps he would let me lay my cheek to his

once more, as he used to do when I was a babe in my

grandmother's arms. I should be glad to say goodby

to him, before I go to my Saviour.”

Gazing intently in his face, she saw the work of the

destroyer in lines too plain to be mistaken.

“My son, my dear son,—say, Lord Jesus, receive my

spirit.”

“Mother,” he replied, with a smile upon his ghastly

features, “He is ready. I desire to go to Him. Hold

the baby to me, that I may kiss her. That is all. Now

shiver with cold.”

He clung, with a death grasp, to that bosom which

had long been his sole earthly refuge.

“Sing louder, dear mother, a little louder. I cannot

hear you.”

A tremulous tone, as of a broken harp, rose above her

grief to comfort the dying child. One sigh of icy breath

was upon her cheek as she joined it to his,—one shudder,

and all was over. She held the body long in her arms,

as if fondly hoping to warm and revivify it with her

breath. Then she stretched it upon its bed, and kneeling

beside it, hid her face in that grief, which none but

mothers feel. It was a deep and sacred solitude, alone

with the dead,—nothing save the soft breathing of the

sleeping babe, fell upon that solemn pause. Then, the

silence was broken by a wail of piercing sorrow. It

ceased, and a voice arose,—a voice of supplication for

strength to endure, as “seeing Him who is invisible.”

Faith closed what was begun in weakness. It became a

prayer of thanksgiving to Him, who had released the

dove-like spirit from its prison-house of pain, that it

might taste the peace, and mingle in the melody, of

heaven.

She arose from the orison, and bent calmly over her

dead. The thin, placid features wore a smile, as when

he had spoken of Jesus. She composed the shining locks

around the pure forehead, and gazed long, on what was

in their stead was an expression almost sublime, as of

one who had given an angel back to God.

The father entered carelessly. She pointed to the

pale, immovable brow.

“See! he suffers no longer.”

He drew near, and looked on the dead with surprise

and sadness. A few natural tears forced their way, and

fell on the face of the first-born, who was once his pride.

The memories of that moment were bitter. He spoke

tenderly to the emaciated mother, and she, who a short

time before was raised above the sway of grief, wept like

an infant, as those few affectionate tones touched the

sealed fountains of other years.

Neighbors and friends visited them, desirous to console

their sorrow, and attended them when they committed

the body to the earth. There was a shady and

secluded spot, which they had consecrated by the burial

of their few dead. Thither that whole little colony were

gathered, and seated on the fresh-springing grass, listened

to the holy, healing words of the inspired volume. It

was read by the oldest man in the colony, who had himself

often mourned. As he bent reverently over the

sacred page, there was that on his brow which seemed

to say, “This hath been my comfort in my affliction.”

Silver hairs thinly covered his temples, and his low voice

was modulated by feeling, as he read of the frailty of man,

withering like the flower of grass before it groweth up;

are as yesterday when it is past, and as a watch in the

night.” He selected from the words of that compassionate

One, who “gathereth the lambs with His arm, and

carrieth them in His bosom;” who, pointing out as an

example the humility of little children, said, “except ye

become as one of these, ye cannot enter the kingdom of

heaven,” and who calleth all the “weary and heavy-laden

to come unto Him, that He may give them rest.”

The scene called forth sympathy, even from manly

bosoms. The mother, worn with watching and weariness,

bowed her head down to the clay that concealed

her child. And it was observed with gratitude by that

friendly group, that the husband supported her with his

arm, and mingled his tears with hers.

He returned from this funeral in much mental distress.

His sins were brought to remembrance, and reflection

was misery. For many nights, sleep was disturbed by

visions of his neglected boy. Sometimes he imagined

that he heard him coughing from his low bed, and felt

constrained to go to him, in a strange disposition of

kindness, but his limbs were unable to obey the dictates

of his will. Then he would see him pointing with a thin,

dead hand, to the dark grave, or beckoning him to follow

to the unseen world. Conscience haunted him with

terror, and many prayers from pious hearts arose, that he

might now be led to repentance. The venerable man

who had read the Bible at the burial of his boy, counselled

to yield to the warning voice from above, and to “break

off his sins by righteousness, and his iniquities by turning

unto the Lord.”

There was a change in his habits and conversation, and

his friends trusted it would be permanent. She, who

above all others was interested in the result, spared no

exertion to win him back to the way of virtue, and to

soothe his heart into peace with itself, and obedience to

his Maker. Yet was she doomed to witness the full

force of grief, and of remorse, upon intemperance, only to

see them utterly overthrown at last. The reviving goodness

with whose indications she had solaced herself, and even

given thanks that her beloved son had not died in vain,

was transient as the morning dew. Habits of industry

which had begun to spring up, proved rootless. The

dead, and his cruelty to the dead, were alike forgotten.

Disaffection to the chastened being, who, against hope,

still hoped for his salvation, resumed its dominion. The

friends who had alternately reproved and encouraged

him, were convinced that their efforts had been of no

avail. Intemperance, “like the strong man armed,” took

possession of a soul, that lifted no cry for aid to the

Holy Spirit, and girded on no weapon to resist the

destroyer.

Summer passed away, and the anniversary of their

arrival at the colony returned. It was to Jane Harwood

a period of sad and solemn retrospection. The joys of

before her, and while she wept, she questioned her heart,

what had been its gain from a Father's discipline, or

whether it had sustained that greatest of all losses,—the

loss of its afflictions.

She was alone at this season of self-communion. The

absences of her husband had become more frequent and

protracted. A storm, which feelingly reminded her of

those which had often beat upon them, when homeless and

weary travellers, had been raging for nearly two days.

To this cause she imputed the unusually long stay of her

husband. Through the third night of his absence, she

lay sleepless, listening for his steps. Sometimes she

fancied she heard shouts of laughter, for the moods in

which he returned from his revels, was various:—but

it was only the shriek of the tempest. Then she trembled,

as if some ebullition of his frenzied anger rang in

her ears. It was the roar of the hoarse wind through

the forest. All night long she listened to these sounds,

and hushed and sang to her affrighted babe. Unrefreshed,

she arose, and resumed her morning labors.

Suddenly, her eye was attracted by a group of neighbors,

coming up slowly from the river. A dark and

terrible foreboding oppressed her. She hastened out to

meet them. Coming towards her house was a female

friend agitated and tearful, who, passing her arm around

her, would have spoken.

“Oh! you come to bring me evil tidings! I pray you,

let me know the worst.”

The object was indeed to prepare her mind for a fearful

calamity. The body of her husband had been found,

drowned, as was supposed, during the darkness of the

preceding night, in attempting to cross the bridge of

logs, which had been partially broken by the swollen

waters. Utter prostration of spirit came over the desolate

mourner. Her energies were broken, and her heart

withered. She had sustained the privations of poverty

and emigration,—the burdens of unceasing, unrequited

care, without a murmur. She had laid her first-born in

the grave with resignation, for Faith had heard the

Redeemer's blessed invitation, “Suffer the little child to

come unto me.”

She had seen him in whom her heart's young affections

were garnered up, become a “persecutor and injurious,”—a

prey to vice the most disgusting and destructive.

Yet she had borne up under all. One hope remained

with her as an “anchor of the soul,” the hope that he

might yet repent, and be reclaimed. She had persevered

in her complicated and self-denying duties, with that

charity which “beareth all things,—believeth all things,—

endureth all things.”

But now, he had died in his sin. The deadly leprosy

which had stolen over his heart, could no more be

“purged by sacrifice or offering forever.” She knew

not, that a single prayer for mercy, had preceded the

There were bitter dregs in this cup of grief, which

she had never before wrung out.

Again the sad-hearted community assembled in their

humble cemetery. A funeral in an infant colony touches

sympathies of an almost exclusive character. It is as if

a large family suffered. One is smitten down, whom

every eye knew, every voice saluted. To bear along the

corpse of the strong man through the fields which he had

sown, and to cover motionless in the grave, that arm which

it was expected would reap the ripened harvest; awakens

a thrill, deep and startling, in the breasts of those who

wrought by his side, during “the burden and heat of

the day.” To lay the mother on her pillow of clay,

whose last struggle with life, was perchance to resign

the hope of one more brief visit to the land of her

fathers,—whose heart's last pulsation might have been a

prayer, that her children should return, and grow up

within the shadow of the school-house, and the church

of God, is a grief in which none save emigrants may participate.

To consign to their narrow, noteless abode, both

young and old,—the infant, and him of hoary hairs, without

the solemn knell, the sable train, the hallowed voice

of the man of God, giving back in the name of his fellow-Christians,

the most precious roses of their pilgrim path,

and speaking with divine authority of Him, who is the

“resurrection and the life,” adds desolation to that weeping,

with which man goeth down to his dust.

But with heaviness of an unspoken and peculiar nature,

was this victim of vice borne from the home that he

had troubled, and laid by the side of that meek child, to

whose tender years, he had been an unnatural enemy.

There was sorrow among all who stood around his

grave,—and it bore features of that sorrow which is

without hope.

The widowed mourner was not able to raise her head

from the bed, when the bloated remains of her unfortunate

husband were committed to the dust. Long and

severe sickness ensued, and in her convalescence, a letter

was received from her brother, inviting her and her child

to an asylum under his roof, and appointing a period

to come and conduct them on their homeward journey.

With her little daughter, the sole remnant of her wrecked

heart's wealth, she returned to her kindred. It was with

emotions of deep and painful gratitude, that she bade

farewell to the inhabitants of that infant settlement, whose

kindness, through all her adversities, had never failed.

And when they remembered her example of uniform

patience and piety, and the saint-like manner in which

she had sustained her burdens, and cherished their sympathies,

they felt as though a tutelary spirit had departed

from among them.

In the home of her brother, she educated her daughter

to industry, and that contentment, which virtue teaches.

Restored to those friends with whom the morning of life

had passed, she shared with humble cheerfulness the

cherished sadness of her perpetual widowhood, in the

bursting sighs of her nightly orison, might be traced a

sacred, deep-rooted sorrow,—the memory of her erring

husband and the miseries of unreclaimed intemperance.

| THE HARWOODS. Water-drops | ||