| | ||

2.

Thomas Judson appears to be the first printer to use in his books the blocks that form the basis for this ornament stock. Whether he purchased them new when he set up shop or second-hand from an earlier printer I have not been able to discover. Thomas, the son of stationer John Judson, took up his freedom on January 16, 1581 (Arber, II, 683), joined John Windet on January 15, 1584, in a partnership agreement drawn for five years,[7] but destined to last scarcely one, and then apparently permitted his privilege of master- printer to lie dormant until 1598 when his name reappears

On February 4, 1600, Thomas Judson, appearing before a whole Court of Assistants of the Stationers' Company, acknowledged that he had sold "all his presses letters & printing stuffe" to John Harrison, and agreed never "to erect printing" nor "use or kepe [in] a printing house as a mr printer hereafter."[8] This new owner of the ornament stock, a young man just admitted freeman to the Company the previous July 9 (Arber, II, 724), was the son of John Harrison the elder, a well established stationer. Because young John was one of four John Harrisons engaged in the printing business in London at about the same time, the clerk usually identified him with care in the Stationers' Register as "John Harrison Junior (or younger), son of Master Harrison the elder"; Arber and Plomer distinguish him from his kin by referring to him as John Harrison (III).

John set up shop under the sign of the White Greyhound in St. Paul's Churchyard,[9] and engaged in both printing and publishing. Occasionally he printed a book for his father, but by July, 1601, he had begun printing books for which he held the right of copy-some theological tracts, later a book on astrology, and in 1604 Stow's popular Summary of the English Chronicles. And what is especially relevant to this study Harrison expanded considerably the ornament stock that came to him from Judson.

One small addition of four initials (A2, C6, H1, and S1)[10] and two ornaments (Nos. 2 and 4) is historically significant because these blocks first appear between 1583 and 1592 in books printed by the well-known stationer John Wolfe, and hence stand as probably the oldest decorations in the stock. Actually only initials A2 and C6 and ornament no. 2 occur in the Harrison-printed books which I have examined; ornament no. 4 appears in a book printed by George Snowdon, Harrison's successor, and initials H1 and S1 first appear in books printed by Nicholas Okes, Snowdon's successor.

The question is whether these decorations were acquired at different times by the three printers involved or whether the six decorations and perhaps others yet unidentified[11] were purchased at one time. The second

There are, however, obstacles to this view. Wolfe, as Hoppe points out (p. 267), changed his activities from those of printer to publisher in 1593 or 1594 and dispersed at least two portions of his ornament stock to Adam Islip and John Windet. Wolfe initials H1 and S1, first occurring in this study in early Okes books, Hoppe discovered in use in Islip-printed volumes (p. 275), and the O3 which Judson employed as early as 1598, while not traceable to Wolfe, looks suspiciously like an initial from a favorite alphabet used by Islip all through the 1590's Therefore, until scholars study in detail the transfer of ornaments at the turn of the century, one can only conjecture that the Wolfe decorations through Islip might have come into the ornament stock here under study by 1598 in the career of Judson, or in 1601 in the time of Harrison, or even in part as late as 1606 when Islip was selling his business to Raworth and Monger, and Nicholas Okes was on the point of leaving his partner Snowdon to set up his own business.

Young Harrison's opportunity to enjoy his newly purchased decorations was short-lived, for his career as a stationer consists of little more than its promising beginning. The last imprint which he signed was dated 1604. He was dead by February 6, 1604 (Arber, III, 275), the day on which the Stationers' Company transferred to John Harrison the elder young John's lone apprentice.

Even briefer than Harrison's career was that of his successors, George and Lionel Snowdon (or Snowden). These kinsmen from Yorkshire had both served their apprenticeships with the London printer Robert Robinson, George receiving his freedom May 11, 1597 (Arber, II, 718), and Lionel admitted freeman on February 13, 1604 (Arber, II, 736). They shared jointly the privilege of master printer and set up shop early in 1605 with printing equipment including the ornament stock bought from the Harrison estate. The S.T.C. records only eight signed imprints issuing from their press, the majority of them religious works published by Clement Knight, George Potter, or Nathaniel Butter.

Plomer fixes the dates of the Snowdon partnership as 1606-1608.[13] The evidence of the Snowdon imprint-dates and the Stationers' records indicate

Nicholas Okes, Snowdon's successor, was the son of John Okes, a horner plying his trade in London. On March 25, 1596, Nicholas started serving his apprenticeship with William King (Arber, II, 209). Okes gained his freedom on December 5, 1603 (Arber, II, 735), and married on December 8, Elizabeth Beswick of St. Mary Magdalen, the daughter of a Gloucester cook.[15] At least two children, John and Mary, sprang from this marriage, both of whom figure later in the history of this ornament stock. On April 19, 1606, Okes was admitted into the livery of the Stationers' Company (Arber, III, 700). The S.T.C. records no items bearing an Okes-Snowdon imprint and lists but one Okes imprint (S.T.C. 10856) in the year 1606.[16] Nicholas did not enter a copy in the Register until July 6, 1607 (Arber, III, 355), several months after he had launched his own business.

Of all the printers considered in this study Nicholas Okes is unquestionably the most significant. He was active as a printer-publisher for some thirty years, longer than any of the others; he printed the largest number of books and stands unchallenged except perhaps by the later William Wilson as the printer of items important in the history of English drama. From Okes' press came play quartos of Armin, Heywood, Jonson, Massinger, Marston, May, Middleton, Shakespeare, and Webster. In addition he printed non-dramatic writings of Braithwaite, Brown, Daniel, and Donne, the travels of Lithgow, and the widely popular farming and livestock manuals of Gervase Markham, a number of whose writings Nicholas both printed and published.

Likewise the books issuing from Nicholas Okes' shop are for this study the most revealing. Okes owned a full ornament stock and drew upon it consistently in decorating the preliminaries of his books and calling attention to new sections or chapter headings, although he seldom decorated

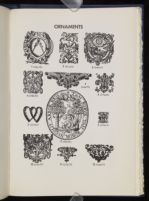

Okes, like many of his contemporaries, reserved a few ornaments for use on his title-pages and employed them frequently enough that they may be considered printer's devices as McKerrow accurately described them when he reproduced all of Okes' some years ago.[17] Only two of the six normally ascribed to Okes were original with him: the fleur de lis in the oval frame (Orn. 4) and the large unframed fleur de lis (Orn. 6) came from John Wolfe; the Pegasus over a caduceus (Orn. 2) and the pair of compasses in the oval frame (Orn. 1) came from Harrison. The small unframed fleur de lis (Orn. 9) first appears in an Okes book in 1608; the large device picturing Jove amid his oak trees and dated 1610 (Orn. 8) Okes used at intervals throughout his printing years. A seventh ornament, a lion's face over a shield without the initials H. M. (Orn. 10) McKerrow attributes somewhat reluctantly to Okes because the device, once the property of Henry Middleton, should have passed to Robinson, to Bradock, and then to Haviland, not to Okes. McKerrow found a single imprint by Okes bearing the decoration and supposed it "possible that he . . . had a habit of putting his name as printer on books really printed for him."[18] This habit Okes may have had, though I came upon no examples of it; but he was not misleading anyone in those books bearing the old Middleton device. There exist at least four other Okes imprints containing the device and including additional blocks identifiable as Okes'. The ornament later passed to John Okes and then through his widow to William Wilson.

Nicholas Okes' life during the thirty-odd years of his career was for an early seventeenth-century London printer not an unpredictable one. He changed his residence or place of business three times: in 1603 he was living in St. Nicholas, Cole Abbey;[19] by 1613 he was situated near Holborn bridge,[20] and by 1628 he was dwelling in St. Leonard, Foster Lane.[21] In the eleven-year span from 1611 to 1621 his father, John; his wife, Elizabeth; and his mother, Grace, all died. He took his son, John, in the same period to be his apprentice and incurred the censure of the authorities for printing Francis of Sales' An Introduction to a Devout Life (Eye) and Withers Motto (1621). By February of 1624 he had taken a second wife, Mary, the widow of Christopher Pursett,[22] a publisher active briefly from 1605 to 1607, and again in 1611. On January 12, 1626, Nicholas' son, John, gained his freedom in the Stationers' Company (Arber, III, 686). The year following Nicholas was again in difficulty with the authorities, this time jointly with John over the printing of Sir Robert Cotton's A Short View of the Long Life and Raigne of Henry the Third. By January, 1628, Nicholas' second wife was dead.

After 1626, the year of John's freedom, the partnership arrangements that Nicholas and his son entered into with each other and with others cannot always be determined with certainty. Plomer and McKerrow both state that John Okes was in partnership with John Norton.[23] The single piece of supporting evidence for that conclusion is the State Paper note that in 1635 "John Okes . . . and John Norton [were] partners under colour of partnership but none of them admitted" (Arber, III, 703), a statement indicating that the relationship was at best a fiction designed to hoodwink the authorities. Plomer states also that in about 1627 Nicholas took his son John as a partner.[24] The available evidence suggests the contrary. During the ten-year period 1625-1634 John Okes inserted his name in only four imprints: two jointly with his father and two alone. Plomer implies that there is proof from a deposition of John and his father's working together on a third book, the unsigned A Short View by Cotton which the government suppressed. In roughly the same years Nicholas was printing almost sixty volumes in which his name appears alone in the imprints and was actively engaged in a partnership with another printer.

The one partnership that Nicholas formed for which irrefutable proof exists is that with John Norton, who before a twelve-year stint as master-printer had served as apprenticed and journeyman in the King's printing

How Okes and Norton managed their cooperative venture can be understood in part by examining the books which each of the men printed. Norton had been a master printer prior to his joining Okes and hence could be expected to retain some of his materials. His types he evidently brought along with him, for the types in his books are consistently different from those in Okes' printing. There is, on the other hand, no evidence that Norton added a second press to the one which Nicholas had possessed from the outset of his career, nor is there any marked indication that Norton retained his old ornament stock.[26] During his years with Okes he seems gradually to have accumulated in his section of the shop a group of Okes' decorations, including some dating back to the era of Judson and Harrison, which he kept separate from the general Okes stock and which he tended to use and reuse in his books.

From these printing practices which characterize the Okes-Norton shop during the period of the partnership, the bibliographer may also infer a possible solution to the problem of distinguishing an unsigned Okes book from one unsigned but printed by Norton between the years 1628 and 1636. Identification of the ornaments in a given book would merely limit the search for the printer to the Okes-Norton shop. Finding in the volume certain of the Okes' blocks which habitually reoccur in Norton imprints would furnish inferential but scarcely proof-positive evidence. Therefore only by a detailed comparative type study-the varying italic capitals in the pica and English fonts offer a speedy trial solution-may the scholar determine with any conclusiveness which man printed the book.

No problem posed by the Okes-Norton partnership is so difficult of solution as that which one faces in attempting to ascertain the precise date

Norton's parting company with Okes, in whatever year it occurred, stripped Norton of even the pretended right to print with the approval of the Archbishop and the Commission. Despite the absence of his name on the Star chamber decree of 1667 listing approved master printers, Norton continued his printing "by indulgence" and on a very insecure footing. He eventually received his license in 1639 (Jenkins, loc. cit.), but within a year or so he had died, intestate -- the inventory of his estate was estimated at a mere £99[27] -- and left his family near to poverty. Alice, his widow, carried on the trade in the early forties and then turned the business over to their son Roger whom Plomer describes as having "died very poor" on November 27, 1658.[28] I have examined no imprints of either Alice or Roger Norton, but both of them doubtless used the decorations which John had

The problem of determining the business relationship between Nicholas and his son after 1634 is almost as puzzling as the one involving Nicholas and Norton. This new problem is complicated by the Okes' running afoul the authorities over the reprinting of Francis of Sales' Introduction to a Devout Life in 1637. As a result Nicholas failed to have his printing privilege reapproved in the 1637 Star Chamber decree. One scrap of evidence suggests that John was responsible for printing the censored Sales' work rather than Nicholas and that the father, ready to retire, took the blame in order that his son might succeed him as master printer without prejudice (CSPD, XV, 212)

From the Okes' imprints dated 1635 and 1636, the years in which Nicholas and Norton were feuding in earnest, one may infer that John was assuming an increasingly important role in the business. In those two years his name, linked always with his father's, appears repeatedly in the imprints. During 1637 John printed several books carrying his name alone. In 1638 and 1639 all but two works emanating from the Okes' shop bear John's signing. Thus John, who between 1635 and 1637 became Nicholas' partner in fact, if not legally, appears to have assumed late in 1637 the role of master in the Okes' house and permitted his father to step down.

This conjectured history of the changing relations between father and son is substantiated in part by Nicholas' petition to Archbishop Laud dated June 28, 1637. In it he professes himself willing to turn over his title as master printer to his son. Nicholas pleads old age as his reason for retirement, and "prays his Grace to allow the said transfer until further order" (CSPD, XI, 249). John's finally taking over his father's business was not, however, without financial strings in the form of annual payments: £ 25 to Nicholas and L50 to John's sister Mary, now married to William Kempe. Within a year Mary followed her father's petition with one of her own requesting Laud to permit John to "subsist, as he now does by favour, and have the reversion of the next printer's place which shall fall void" (CSPD, XIII, 221) The reason for Mary's action is understandable. John, fearing hindrance in pursuing his craft, had refused to perform his agreement and pay Mary the £50 which he had promised her.

The facts concerning John's life and career between 1637 and 1643, the year of his death, are quickly set down. He was elevated to the livery of the Stationers' Company on June 1, 1640,[29] and presumably by that date had received from the government his license to practice his trade. From his will drawn on July 15, 1643, most of these remaining facts may be inferred.

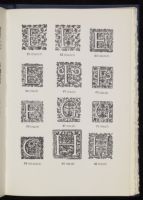

The single most important contribution which the books bearing John Okes' imprint make to this study is the evidence throughout that a large new stock of decorations has been added to the old collection. The new blocks, both ornaments and decorative initials, make their appearance first in 1636, the year in which John joined his father actively as a partner at about the same time Nicholas and Norton were parting company.

The stock which Nicholas had employed so consistently from the start of his career was by now worn and because of Norton's "borrowings" somewhat incomplete, but the decision to purchase a new stock turned in all probability on Nicholas' desire to give the publications issuing from his house a modern appearance and to launch John on his career with fresh materials. This new ornament stock, except for a few additions, seems to have served John and his successors well during the next half-century. They did not, however, discard the original stock; old familiar blocks continue to appear but much less frequently now and quite unpredictably. For the bibliographer, a knowledge of the decorations in both the old and new stocks and of the circumstances surrounding their merger is from this point on of particular value, for the six printers who use these blocks during the next fifty years will be leaving unsigned the imprints of many of their books and will at the same time be printing a good portion of the significant belles lettres in mid-seventeenth- century London.

Once John Okes had died, his widow Mary had virtually no choice but to take up the responsibility of running the printing shop. The Stationers' Company honored the right of widows to succeed their husbands in the trade, John had paved the way by stipulations in his will, and Mary had two sons and a father-in-law to support. Fortunately she could depend on the shrewd counsels of Nicholas Okes to guide her and probably could count on the assistance of William Kirby and Adam Hare, two journeymen whom John had remembered in his will. She signed her first imprint in 1643; the earliest I have found is Daniel Swift's The Pious Protestant

She ran the shop for about two years and then turned over its direction to the printer William Wilson, whom she married in 1645. When precisely all these events in the lives of John and Mary Okes and Wilson occurred, the parish registers of Little St. Bartholomew fail to say. They are silent on the dates of both of Mary's marriages, on the birthdates of her two sons and the death dates of her father-in-law and even of her husband John, who had requested to be buried in the Little St. Bartholomew sanctuary "as near to the chancel as may be with convenience."[31]

Mary's new husband, the printer William Wilson, Plomer barely mentions in his Dictionary 1641-1667; he even questions whether Wilson was active in London (p. 196), but more recent scholars concentrating on the study of London printing after 1640 have found, of course, abundant evidence of the activity of Wilson's presses.[32] William, the son of the late Thomas Wilson, a yeoman living at Meldreth in Cambridgeshire, "put himself apprentice" on July 25, 1618, to the London stationer Thomas Dawson for a term of nine years. Wilson was officially bound on November II, 1618, and after Dawson's death, was "put over by Consent of a Court" to Thomas Purfoote on April 9, 1621, to serve the residue of his unexpired term.[33] Purfoote turned Wilson over to the Stationers at the end of an eight rather than nine-year term, and on September 4, 1626, the young man was sworn and admitted freeman of the Company (Arber, III, 686). Apparently lacking the opportunity and funds to set up as a master printer, he labored for most of the next twenty years as a journeyman. He ventured only once in these early years to make a Register entry; the copy, a broadside, was listed on July 7, 1628, and assigned to Edmond Whiting on February 5, 1640.[34]

Wilson's opportunity came in 1645 with his marriage to Mary Okes. He was in his early forties, almost an exact contemporary of Mary's first husband, and evidently a widower with one daughter Sarah.[35] With this

The greater portion of the books which Wilson printed mirror the shoddy printing standards of his day; his significance rests in the fact that he printed for Humphrey Moseley and Henry Herringman, the two leading London publishers of contemporary literature. He shared Moseley's printing with Thomas Warren, and Herringman's with John Macock, but Wilson's was always the lion's share. He is the only active printer mentioned by Moseley in his will,[41] and Herringman is the only bookseller-publisher mentioned in Wilson's will, suggesting that Wilson enjoyed more than a strictly business relationship with both publishers. From his presses came the huge French romances of La Calprenède and Scudéry in translation, the early theological and scientific writings of Robert Boyle, poetry by Cowley, Dryden, Fane, King, and Waller, and plays of Beaumont and Fletcher, Davenant, Dryden, Porter, Tuke, and Shirley.

Wilson employed consistently and at times lavishly the new decorations which Nicholas and John Okes had purchased in 1636 and mingled with them occasionally the blocks from the earlier stock, including four or five of the very earliest acquired originally from John Wolfe. He bought additional decorations of his own, and because he printed numerous folios and quartos, tended to use more large ornaments and block initials than the Okeses did. His persistent use of the same small group of headpieces, a handful of initials, and two devices, ornaments no. 5 and II, makes the identification of his presswork relatively simple-a boon indeed when one considers the fact that he signed something less than fifty per cent of the output of his printing house. Of the 53 pieces which he printed for Herringman in the years 1653-1665, for example, Wilson inserted his name or

Wilson's career as a master printer covers exactly twenty years. He married Mary Okes in 1645 and died in the spring of 1665-his will was probated on May 8, 1665.[42] In it he bequeathed L100 of his share in the English Stock to his daughter Sarah Chalfont and the remaining £60 to "my loveing and obedient [step-]sonne Edward Oakes," to whom Wilson also willed his "printing house and all ymplements thereunto belonging," with the understanding that Mary Wilson was to enjoy sole interest in the shop as long as she desired or until her death. The widow was soon to turn the responsibility for the business over to Edward. On August 5, 1665, "weake and ill" she was affixing her mark to her will.[43] Nor was she the only one attentive to the arranging of her worldly affairs. Pepys, in the same week, hearing that the Bill of Mortality had listed 3000 deaths from the plague was drawing over his will anew, observing at the time, the town grows so unhealthy "that a man cannot depend upon living two days."[44] Mary's death seems to have occurred shortly thereafter; by December Edward ventured without undue risk to attend to the probating of his mother's will and probably the reopening of his printing shop.

Both of Mary's sons, John Jr. and Edward, taking advantage of their patrimonial privilege, had become free of the Stationers' Company-John Jr. on April 7, 1662, and Edward on June 27, 1664[45] _ but evidently it was the younger Edward, who proving the more reliable and industrious of the two, had been rewarded by his stepfather with the business. Edward was clothed by the Stationers on June 30, 1668.[46] A survey of London presses made in the next month describes Okes as having two presses, no apprentices, and only two workmen.[47] He is listed as one of four printers "set up since ye Act [of 1662] and contrary to it."[48] L'Estrange planned to indict the other three printers at the next Quarter Sessions;[49] how and why Okes escaped a like charge one can only guess.

Edward's career runs from 1666 to 1672, possibly into early 1673, although I have found no imprint dated after 1672. In this interval he printed only an occasional volume for Herringman, who after the London fire gave the bulk of his large printing business to his new neighbor in the

Okes married Ann Cocke, a widow, of St. Martin, Ludgate, two years his senior, on April 23, 1672 (Foster, loc. cit.), and bequeathed to her his "coppyes Letters Printing Presses and Tooles in a will drawn April 18, 1673, and executed on May 27.[50] On June 16 she assigned a group of the most popular of Edward's copies to Thomas Vere and John Wright.[51] By June 30, the day on which the clerk entered the assignment in the Stationers' Register, Ann also was issued a commission to administer the "goods rights and credits" left unadministered in the wills of her late husband's mother and stepfather, William Wilson.[52] Ann Okes' alacrity in winding up the affairs of Edward's estate suggests that she was either desperately in need of ready money or very anxious to get her hands on some.

At about the same time, or as soon as she could find buyers, she must have busied herself likewise in disposing of Edward's printing materials. His extensive ornament stock, the accumulation of three generations of Okeses and William Wilson, eventually fell into the hands of Robert White,[53] a long established printer of religious matter in Warwick Lane, described in the press survey of 1668 as operating three presses and employing three apprentices and seven workmen.[54] Once White came into possession of Okes' blocks-I found White using them first in 1674-he appears to have employed no other ornamentation despite the fact that his earlier imprints reveal a ready stock which is attractive and not noticeably worn. White continued inserting his newly bought decorations in his books until his death about June 30, 1678.[55] His widow Margaret assumed immediate charge of the business, which had been willed to her, and continued to use the ornament stock in her presswork until she ceased activities late in 1682 or early in 1683.

Who next used the blocks in these final decades of the seventeenth century when London printers tended to devote little or no book space to ornamentation I have not been able to learn. Bernard White, formerly an

| | ||