| | ||

Thomas Newcomb: A Restoration Printer's Ornament Stock

by

C. WILLIAM MILLER

THE MANY EXTANT AND READILY ACCESSIBLE books signed by the printer Thomas Newcomb afford a particularly good starting point in the large and tantalizingly complicated study of printers' ornaments in the Commonwealth and Post-Restoration periods.

Newcomb was active as a printer for thirty-three years: he was the master of a large printing shop, and after the great fire became one of a handful of men who dominated London printing. Newcomb owned and employed a large assortment of ornaments which have a history of use totaling approximately fifty years, if one counts that group in use ten years before Newcomb acquired it and those which Newcomb's son used for at least seven years after his father's death. Finally, Newcomb printed well over a thousand items, a large number of them for the patentees of the King's Printing Office, but an even greater number for more than a score of stationers, including Henry Herringman, the foremost publisher of belles lettres in Post-Restoration London. Hence, one finds few prominent writers of history, science, theology, or literature in the last half of the century who had not had one or more compositions run off Newcomb's presses.

Obviously a definitive study of the many ornaments in Newcomb's thousand or more publications must await first the appearance of Mr. Wing's Short-Title Catalogue . . . 1641-1700, Volume III, and then the labors of other students. In this paper I attempt only to summarize the history of transmission of ornaments owned by Newcomb, to set down my observations on how ornaments were used in Newcomb-printed books, to offer some suggestions

The history of a portion of the ornaments used by Newcomb begins in 1638[1] with the emergence of John Raworth as a London printer. I have examined far fewer of his publications than those of Newcomb, but my impression is that his ornament stock was a good-sized one. He owned a wide variety of decorative initials and many large, generally attractive ornaments; he preferred initials to factotums, and used both the initials and ornaments generously, especially in folios. The clearness and completeness of impression which many of his ornaments make would suggest that the bulk of his stock was newly purchased rather than bought up from some other printer. This observation is of course only conjectural. I have not tried to trace Raworth's ornaments in the books of earlier printers.[2]

Raworth's career as a printer was cut short by his death late in July of 1646. The uninterrupted flow of religious pamphlets from the Raworth presses indicates, however, that John's widow, Ruth, assumed charge of operations at once. Her activity as a printer extends to 1648 when she married Thomas Newcomb, who had just become free of the Stationers' Company after serving a seven years' apprenticeship under Gregory Dexter.[3] Throughout her brief career Ruth Raworth used the ornaments at hand in her shop, and since the kinds of books she printed made no extraordinary demands on her ornament supply, the likelihood is that she added few or no ornaments to her late husband's collection.

Once Newcomb had married Ruth Raworth, he seems to have taken over the direction of her shop, located on Thames Street

Newcomb died suddenly on December 26, 1681, as one ardent conventicleer would have it, struck down by God in the king's presence for hating protestant dissenters.[4] His printing equipment, including his ornaments, and his patent rights in the King's Printing Office were inherited by his only son, Thomas Newcomb, Jr., also free of the Stationers' Company, who remained active as a printer in the Savoy until July, 1688, when Edward Jones moved into the Savoy and took over the printing of the London Gazette. Whether the son ceased printing at this point or set up shop elsewhere and continued actively in his trade is difficult to ascertain.[5] There is no question about the fact that he managed, despite the political upheaval, to maintain the right to publish some types of official documents and that he, his executrix, and his assigns continued exercising those rights well into the eighteenth century.

Equally difficult to determine is when Thomas Newcomb, Jr.,

2.

From the outset of his career Thomas Newcomb was associated with a comparatively large and well established printing house, which grew even larger as he prospered in his trade. The observations which one formulates, therefore, on how ornaments were used in Newcomb-printed books can only be those reflecting the general policy of his shop, and not a list of typographical idiosyncrasies of the master himself. The practice of Newcomb's compositors in handling book decorations compared with that of the printing houses of several of his contemporaries indicates, however, that Newcomb's practice was in almost every respect typical.

During the Interregnum and the early years of the Restoration Newcomb tended, like the other printers of that day, to use more ornaments and initials throughout the text of his octavos and quartos than he did in the late 1660's and 1670's. His folios were generally his most elaborately ornamented volumes, although he seldom decorated them so lavishly as did his predecessor Raworth.

From 1667 to 1675 Newcomb used few ornaments in his smaller formats and only a sprinkling of initials and factotums throughout the text. The ornamentation in his play quartos was confined entirely to the initial gatherings: a headpiece and initial or factotum on the recto of the second leaf which was usually reserved

After 1675 he used even less ornamentation in his play quartos than he had before that date, reaching a point finally about 1679 when he omitted it altogether. In this omission he was only following the practice of his fellow London printers, many of whom had been turning out ornament-less play quartos since the early 1670's. In attempting to identify the printers of unsigned quarto plays published in 1679 or thereafter for the next thirty years, the bibliographer finds a knowledge of printers' ornaments practically valueless.

In the many normal and oversized folios issuing from his presses, one finds Newcomb's most elaborate book decorations. As a rule printers generally tended to pay deference to their folio ornamentation. Newcomb's practice was to use headpieces and initial decorations profusely in the initial gatherings. Thereafter for about two-thirds of the volume he used ornaments and factotums to mark only fresh divisions of text. The final third was often devoid of decoration.

Generally Newcomb seemed slightly fonder of using ornamentation after the Restoration than those among his contemporaries whose books I have examined, and was markedly more generous in their use than his important competitor John Macock. Yet one comes upon enough exceptions to most of the generalizations made so far in this section to conclude that the price the publisher was willing to pay and the reading public for which he intended his publication dictate more often than not the amount of paper space the printer took up with decorations. Thus in a period when Newcomb employed ornaments rather consistently, his quarto edition of Nedham's Interest Will Not Lie (1659) and his folio printing of Certain Letters Evidencing The King's Stedfastness in the Protestant Religion (1660) are without ornamentation while in a period of dwindling ornamentation, even in folios, Newcomb's folio edition of The Genealogical History of the Kings of England (1677), privately printed for the herald Francis Sandford, turns out to be perhaps the most attractively and profusely decorated volume of Newcomb's printing career.

There are apparently no practices dealing with ornaments that

On the other hand, there are a few positive practices worth mentioning. After 1666 Newcomb used factotums far more frequently than he used initials, and he used over and over the same small group of ornaments. He made some effort to decorate books authorized by or dedicated to the king with appropriate national and Stuart ornaments. The only other occasion on which a Newcomb compositor appeared concerned about using a particular ornament in a particular place—and this applies to compositors in other printing houses as well—was when he was working on a reprint of a volume previously issued from his shop. Then he would often reproduce in the new edition the identical ornament used perhaps five or ten years earlier, despite the fact that searching for it in his collection must frequently have involved a considerable waste of time.

3.

Simple as the bibliographical technique is of using an ornament chart to identify the unsigned books of a printer, it has occasionally its pitfalls, and hence for the guidance of bibliographers

English ornament makers of this period show a marked tendency to copy and recopy earlier designs rather than create new ones. Those copies made in wood are more often than not distinguishable from each other, but on occasion recuttings were made with such precision that one is hard put to tell them apart. The many decorations made from metal rather than wood present a greater problem in that indistinguishable copies of an ornament cast from the same matrix were owned and regularly used by as many as a half-dozen printers. Wherever I have found a printer using an ornament very similar to Newcomb's, I have made a note of it after the list of occurrences; but since I have concentrated in this study on the ornaments of only a handful of printers and since there are tens of thousands of books which I have not seen, the likelihood is that future study will uncover very similar or indistinguishable copies of Newcomb ornaments in the stock of other printers.

Measurements of ornaments are helpful in distinguishing between like ornaments but furnish conclusive evidence only where there is a marked difference in size between two otherwise identical ornaments. Different impressions of the same ornament vary in measurement because of light or heavy inking, newness or wear, or variable degrees of shrinkage in the paper. In the Newcomb chart I have at times given measurements down to a half millimeter; one should not, however, consider them other than the average, often made up from several varying measurements.

A knowledge of printers' type-ornaments is generally useless in attempting to identify a particular printer in this period. I have found no one of Newcomb's many type-ornaments that was not also in the stock of other printers.

When the identification of the printer of an unsigned book depends on the decorative initials H, I, O, or S, one should be sure to examine the letter both right side up and upside down. Compositors paid little attention to the proper position of such letters, and looked at wrong side up, these letters often present quite a different appearance.

Ornaments in the text of a volume occasionally qualify or contradict the evidence of a printer's name in the title-page imprint.

Finally, in attributing to a specific printer the presswork of an unsigned book, one is always on surer ground if he can buttress the evidence of the ornamentation with that derived from other reliable sources. One of the obvious sources is the printer-employment habits of the stationer publishing the book. A study of the imprints on books published by Herringman, for example, reveals that he tended to patronize one or two printers consistently in a given period. Therefore anyone attempting to identify the printer of a Herringman volume can eliminate from consideration almost immediately all but the handful of likely candidates; and where the volume in question contains ornaments known to be used by several printers, one can on occasion establish with great probability the one printer whom Herringman hired to do his work.

The other source is the wills of the printers with the appended probate statements. Ornament stocks seem to have passed almost overnight from one printer to another, and therefore it is frequently necessary to determine the terminal dates of a printer's activity, lest one interpret the evidence of the ornaments erroneously. For instance, the evidence of ornaments supported by that of the imprints suggests that Thomas Newcomb, Sr., was active as a printer from 1648 to 1691. The probate date of his will indicates, however, that he died late in 1681, and the text of the will points to the fact that Newcomb's son, who happened to have the same name as his father's, inherited the ornament stock and was

4.

The following is a list of occurrences which I have found of the Newcomb ornaments, factotums, and initials pictured in the final pages of this study. Each of the three types of ornamentation has its own heading and separate series of numbers. The entry for each decoration contains this information: (1) an identifying number corresponding to that accompanying the picture of the decoration; (2) the approximate millimeter measurements, with the vertical measurement occurring first; (3) a listing of the books in which the particular decoration is to be found, chronologically arranged and subdivided among the various printers who owned and used the decoration during specific periods of years. "RAWORTH" means always John Raworth, active from 1638 to 1646; "R. RAWORTH", Ruth Raworth, 1646-1648; "NEWCOMB," Thomas Newcomb, Sr., 1648-1681; "NEWCOMB JR.," Thomas Newcomb, Jr., 1682-1688(?). Books in the following list printed before or during 1640 are cited according to the numbers assigned them in the Pollard and Redgrave S.T.C. The remainder are cited according to the numbers given them in the three volumes of the Wing S.T.C.; the numbers of books listed in the unpublished third volume have been supplied from proof sheets through the courtesy of Mr. D. G. Wing and the Princeton University Library. The occasional book not found listed in either S.T.C. is cited by short title. Where Wing has assigned only one number to a play known to appear in two editions during a single year, I have appended to the Wing number the numbers assigned the different editions by Woodward and McManaway in A Check-list of English Plays 1641-1700. The brackets enclosing any S.T.C. number indicate that the book has been identified by means of the ornaments as

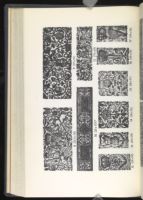

The decorations pictured are reproduced usually at approximately life-size; those pictured at less than life-size—generally reduced about one-fifth—are marked with an asterisk accompanying the measurements beneath the picture.

- 1. (28 x 102 mm) RAWORTH—1642: H1978; 1644: K738. R. RAWORTH— 1646: P480; 1647: G2714. NEWCOMB—1653: M2868; 1660: C4979; 1668: [D2327], H2991, H2996, J1161, S2878, [S6322]; 1669: D2399, D2400, [E3370]; 1671: B4405, [C746], T3231; 1672: D2256; 1673: D2241; 1675: S2866(W & McM 1086, 1087), D2348; 1677: D2372; 1678: B1588, B3984, D2242; 1679: H1577. J. MACOCK— 1688: C6658; 1693: [C6659].

- 2. (16.5 x 86 mm) RAWORTH—1641: D1109. R. RAWORTH—1646: P1703. NEWCOMB—1645[9]: R1258.

- 3. (18 x 35 mm) RAWORTH—1644: K738. NEWCOMB—1656: B3334; 1669: H2965.

- 4. (46 x 45.5 mm) NEWCOMB—1650: R1236; 1651: D324, D325; 1668: [O480]; 1673: D320; 1676: O490.

- 5. (18 x 33 mm) NEWCOMB—1663: M134.

- 6. (25 x 92 mm) RAWORTH—1641: W1419; 1642: C845, H1978, N249; 1644: C830, C839, C845, C846, H340, L404, S2138, S2381, S5970. R. RAWORTH—1645: B5680, B5688, C3812; 1646: S479. NEWCOMB— 1650: R1236; 1653: M2868; 1661: W3657; 1668: [W515]; 1669: H2965.

- 7. (20 x 92 mm) RAWORTH—1644: S2381. R. RAWORTH—1646: C826. NEWCOMB—1656: M2103; 1661: W3657; 1668: [D2327], S2878.

- 8. (35.5 x 78 mm) RAWORTH—1644: K738. NEWCOMB—1656: B3334.

- 9. (37 x 91 mm) RAWORTH—1641: W1419; 1644: K738, L404, W3429. R. RAWORTH—1645: B459. NEWCOMB—1645[9] : R1258; 1649: P4129; 1650: E326, R1236; 1654: H360; 1655: D1453; 1658: N1313; 1660: C4979; 1666: H2631; 1668: [D2327]; 1669: [D2347]; 1672: D2256; 1673: D2257, D2306; 1675: D2348, S2866(W & McM 1086, 1087); 1679: E3344.

- 10. (25 x 137 mm) NEWCOMB—1666: H2631; 1671: D2489; 1673: D320; 1677: C200; 1678: D414.

- 11. (19 x 69 mm) RAWORTH—1643: L2783 A. R. RAWORTH—1645: M2160. NEWCOMB—1657: R1291; 1658: H1177; 1660: R1239.

- 12. (39 x 20 mm) RAWORTH—1644: K738. R. RAWORTH—1647: D413. NEWCOMB—1650: L129; 1655: [C581]; 1660: G2040.

- 13. (39 x 20 mm) RAWORTH—1644: K738. NEWCOMB—1655: [C581]; 1660: G2040.

- 14. (38 x 32 mm) RAWORTH—1644: K738. R. RAWORTH—1645: M2160 NEWCOMB—1651: D325; 1655: [C581], D1453; 1656: B3334; 1660: C4979; 1666: H2631; 1668: [C6324]; 1669: O501; 1673: D320.

- 15. (38 x 31 mm) RAWORTH—1644: K738. NEWCOMB—1650: L129; 1651: D325; 1654: H360; 1655: [C581]; 1656: B3334; 1657: [M1985]; 1666: H2631.

- 16. (39 x 20 mm) R. RAWORTH—1647: D413. NEWCOMB—1660: G2040.

- 17. (39 x 20 mm) NEWCOMB—1650: L129; 1660: G2040.

- 18. (24 x 79 mm) NEWCOMB—1645[9]: R1258.

- 19. (29.5 x 123 mm) NEWCOMB—1666: H2631; 1669: D2399, D2400; 1673: D320; 1673/74: P1593; 1676: O490; 1678: T2826. NEWCOMB JR.—1691: [B3341]. J. MACOCK—1688: C6658; 1693: [C6659].

- 20. (28 x 138 mm) NEWCOMB—1666: H2631; 1671: D2489.

- 21. (33 x 130 mm) NEWCOMB—1654: H360.

- 22. (32 x 30 mm) NEWCOMB—1651: D325; 1671: [C746]; 16779: L2709.

- 23. (37.5 x 96 mm) NEWCOMB—1658: S646; 1673: D2232, D2241, D2306; 1675: S2866(W & McM 1086, 1087); 1676: [G2177], S2883; 1679: B839, H1577, L2709. NEWCOMB JR.—1684: [D2328]. (Variations of this ornament were common. For variant most like Newcomb's see H. HILLS—1654: C5808.)

- 24. (21 x 74 mm) NEWCOMB—1666: H742; 1668: [B4027], C1922; 1669: D1872.

- 25. (25 x 108 mm) NEWCOMB—1675: C7377; 1676: [C2777].

- 26. (44 x 51 mm) NEWCOMB—1660: C4979.

- 27. (39 x 157 mm) NEWCOMB JR.—1685: C5387.

- 28. (44 x 48 mm) NEWCOMB—1678: D414.

- 29. (45 x 145 mm) NEWCOMB JR.—1685: C5387.

ORNAMENTS

- 1. (57 x 57 mm) RAWORTH—1644: K738. NEWCOMB—1653: H360; 1660: C4979.

- 2. (15.5 x 15 mm) NEWCOMB—1655: C581; 1656: B3334.

- 3. (59 x 60 mm) R. RAWORTH—1647: D413. NEWCOMB—1653: H360; 1655: D1453; 1660: H2631.

- 4. (43.5 x 45 mm) NEWCOMB—1666: H2631; 1677: S651.

- 5. (22 x 20.5 mm) NEWCOMB—1645[9]: R1258; 1661: L130; 1663: M134.

- 6. (42 x 43 mm) NEWCOMB—1660: C4979.

- 7. (32.5 x 32 mm) RAWORTH—1644: K738. R. RAWORTH—1647: D413. NEWCOMB—1656: M2103; 1666: H2631; 1668: B4027.

- 8. (25 x 25 mm) NEWCOMB—1663: M134. NEWCOMB JR.—1684: [C3667].

- 9. (21.5 x 21.5 mm) NEWCOMB—1663: M134.

- 10. (64 x 64 mm) NEWCOMB—1673/4: P1593; 1677: O499, S651. NEWCOMB JR.—1685: C5387.

- 11. (61.5 x 64 mm) NEWCOMB—1673: D320, D2232; 1677: C200. NEWCOMB JR.—1685: C5387.

- 12. (33 x 33 mm) NEWCOMB—1668: H2996, [W515]; 1669: D1872. NEWCOMB JR.—1684: [C3667].

- 13. (35 x 36.5 mm) NEWCOMB—1671: D2489; 1677: S651.

- 14. (32.5 x 33 mm) NEWCOMB—1666: H2631; 1668: [B4027]; 1671: D2489.

- 15. (35.5 x 35.5 mm) NEWCOMB—1669: [E3370], H2965; 1673: D320; 1675: S2866(W & McM 1086, 1087); 1676: D2480, O490; 1677: D2743; 1678: D2229; 1679: B839. NEWCOMB JR.—1684: [D2328]; 1685: C5387.

- 16. (27 x 30.5 mm) NEWCOMB—1668: [D2327].

- 17. (34 x 35 mm) NEWCOMB—1669: D2399, D2400; 1671: S2851; 1672: D2256; 1673: D320, D2241, D2306; 1676: O490, S2857; 1677: C200, S651.

- 18. (26 x 30) NEWCOMB JR.—1689: C4150.

- 19. (35 x 35 mm) NEWCOMB—1673: D2257; 1677: S651; 1678: D2242. NEWCOMB JR.(?)—1691: [S2852].

- 20. (27 x 28 mm) NEWCOMB—1666: H742; 1668: E323; 1669: E3490; 1671: J1159.

- 21. (55 x 53 mm) NEWCOMB—1676: O490; 1677: C200, S651; 1678: D414. NEWCOMB JR.—1683: M1958; 1685: B4186, C5387.

- 22. (28 x 27 mm) NEWCOMB—1675: D2348; 1677: D2724, S651.

- 23. (38 x 39 mm) NEWCOMB—1675: D2480; 1676: O490; 1677: O499, S651; 1678: D414; 1679: [B1582], H1577. NEWCOMB JR.—1684: B4194, H507; 1685: B4186.

- 24. (31.5 x 32.5 mm) NEWCOMB—1674: B6311; 1675: C7380, D2160, D2348; 1677: D2372, S651; 1678: B1588, D414, L305; 1679: [B1582], H1577, L2709. NEWCOMB JR.—1682: [W516]; 1686: [W517]. EDW. JONES—1692: [D2230].

- 25. (24 x 24 mm) NEWCOMB—1675: [B3860]; 1676: O476; 1677: C200; 1679: [B1582], E3344.

- 26. (31 x 32 mm) NEWCOMB—1675: [B3860]; 1676: O490, O499, S2857; 1677: C200, D2372, S651; 1678: D414; 1679: [B1582].

FACTOTUMS

- A

- 1. (31 x 30 mm) RAWORTH—1644: K738. R. RAWORTH—1647: D413. NEWCOMB—1649: [P4129]; 1660: C4979; 1666: H2631.

- 2. (21 x 23 mm) RAWORTH—1640: 23313. NEWCOMB—1650: L129; 1656: B3334; 1663: M134.

- 3. (23 x 22 mm) NEWCOMB—1674: B6311; 1675: D2160.

- 4. (28 x 29 mm) NEWCOMB—1669: H2965; 1671: D2273-4; 1678: B3984.

- 5. (37 x 36 mm) NEWCOMB—1676: D2480; 1677: S651. NEWCOMB JR.—1684: [D2328].

- 6. (44 x 44 mm) NEWCOMB—1666: H2631; 1668: [D2327], [S6322]; 1677: S651.

- 7. (20 x 20.5 mm) NEWCOMB—1661: L130; 1675: B4025.

- 8. (18 x 18 mm) NEWCOMB—1679: [B1582].

- 9. (31.5 x 29.5 mm) NEWCOMB JR.—1685: [S2915-17].

- B

- 10. (32 x 31 mm) NEWCOMB—1655: M245; 1677: S651.

- 11. (32 x 31 mm) NEWCOMB JR.—1685: [S2915-17].

- 12. (21 x 20.5 mm) RAWORTH—1643: L2783A. NEWCOMB—1657: R1291; 1674: B6311; 1675: C7377; 1677: D2724.

- 13. (16 x 16 mm) NEWCOMB—1679: [B1582].

- C

- 14. (32 x 31 mm) NEWCOMB JR.—1685: [S2915-17].

- 15. (32 x 34 mm) NEWCOMB—1650: R1236.

- D

- 16. (23 x 22 mm) NEWCOMB—1663: M134; 1674: B6311.

- E

- 17. (31 x 31 mm) NEWCOMB JR.—1685: [S2915-17].

- 18. (23 x 21 mm) NEWCOMB—1650: E121.

- F

- 19. (31 x 29 mm) NEWCOMB—1666: H2631; 1678: D414.

- 20. (40 x 40 mm) NEWCOMB—1654: H360.

- 21. (25 x 24 mm) NEWCOMB—1655: D1453.

- G

- 22. (22 x 24 mm) NEWCOMB—1652: J. Despagne, The Eating of the Body of Christ; 1676: O490; 1677: C200.

- 23. (18 x 18 mm) NEWCOMB—1679: [B1582].

- 24. (24 x 24 mm) NEWCOMB—1669: [E3370].

- H

- 25. (31.5 x 32.5 mm) RAWORTH—1644: K738. NEWCOMB—1661: W3657; 1666: H2631; 1671: T3231.

- 26. (31.5 x 32.5 mm) NEWCOMB—1673: D2257; 1676: D2480; 1677: S651. 1678: B3984.

- 27. (31.5 x 32.5 mm) NEWCOMB—1672: D2256.

- 28. (32.5 x 33 mm) NEWCOMB—1658: S646.

- 29. (22 x 24 mm) RAWORTH—1644: K738. R. RAWORTH—1645: B459, M2160. NEWCOMB—1645[9]: R1258; 1650: L129; 1656: B3334; 1657: R1244; 1668: S2878; 1671: J1159.

- I

- 30. (30 x 29 mm) NEWCOMB—1645[9]: R1258; 1655: C581, D1453.

- 31. (32 x 32 mm) NEWCOMB—1651: D325.

- 32. (16 x 15 mm) RAWORTH—1642: H1978; 1644: C830. NEWCOMB—1652: J. Despagne, op. cit., D1866; 1656: H1177; 1657: [M1985]; 1661: L130; 1663: M134.

- 33. (30 x 29 mm) NEWCOMB—1656: M2103; 1658: R1287.

- 34. (32 x 30 mm) NEWCOMB—1676: [B1676], O490. NEWCOMB JR.—1685: [S2915-17].

- K

- 35. (31 x 32 mm) NEWCOMB—1677: S651.

- L

- 36. (32 x 31 mm) NEWCOMB JR.—1685: [S2915-17].

- 37. (33 x 34 mm) NEWCOMB—1650: L129; 1660: C4979; 1677: C200, S651.

- 38. (67 x 67 mm) NEWCOMB JR.—1685: C5387.

- M

- 39. (20 x 20 mm) NEWCOMB—1669: H2965; 1673: D320; 1679: [B1582].

- 40. (32.5 x 32.5 mm) R. RAWORTH—1647: D413. NEWCOMB—1666: H2631; 1673: D320; 1678: D414.

- N

- 41. (32 x 31 mm) NEWCOMB JR.—1685: [S2915-17].

- 42. (18.5 x 17 mm) NEWCOMB JR.—1685: [S2915-17].

- 43. (32 x 31 mm) R. RAWORTH—1647: D413. NEWCOMB—1650: L129; 1660: C4979.

- O

- 44. (23 x 22.5 mm) RAWORTH—1642: C235; 1645: B5688. NEWCOMB—1657: R1291; 1659: M2101; 1660: R1239; 1669: D1872, H2386. NEWCOMB JR.—1684: [C3667].

- 45. (31 x 30.5 mm) NEWCOMB—1675: D2480.

- 46. (23 x 21.5 mm) NEWCOMB—1675: F408.

- P

- 47. (39 x 37 mm) NEWCOMB JR.—1685: C5387.

- 48. (22 x 22 mm) NEWCOMB—1668: E323.

- 49. (32 x 30.5 mm) NEWCOMB JR.—1685: [S2915-17].

- Q

- 50. (32 x 33 mm) NEWCOMB—1677: S651.

- S

- 51. (39 x 40 mm) NEWCOMB—1671: B4405; 1673: D320.

- 52. (31.5 x 31.5 mm) NEWCOMB—1651: D325; 1666: H2631.

- 53. (23 x 23 mm) NEWCOMB—1650: R1236; 1653: M2868; 1654: T3114; 1668: J1161; 1676: S2883(W & McM 1102, 1103).

- 54. (32 x 31 mm) NEWCOMB JR.—1685: [S2915-17].

- 55. (22 x 22 mm) NEWCOMB—1660: C4979.

- T

- 56. (21 x 20.5 mm) RAWORTH—1642: C235, C846; 1644: S2138. R. RAWORTH—1646: P3401; 1647: D413. NEWCOMB—1648: E3229; 1652: D1866; 1658: H1177, R1287; 1659: M2101.

- 57. (25.5 x 25 mm) NEWCOMB—1645[9]: R1258.

- 58. (24 x 22.5 mm) NEWCOMB—1650: M2113; 1654: H360; 1659: R1244.

- 59. (23.5 x 23 mm) NEWCOMB—1650: M2113.

- 60. (30.5 x 32.5 mm) NEWCOMB—1653: M2868.

- 61. (20 x 21 mm) NEWCOMB—1652: J. Despagne, op. cit.

- 62. (23.5 x 21.5 mm) RAWORTH—1641: C845; 1644: C830. NEWCOMB—1657: D2148.

- 63. (33 x 32 mm) NEWCOMB—1658: [S646]; 1666: H2631.

- 64. (24.5 x 23.5 mm) NEWCOMB—1661: W3657; 1663: M134; 1666: H2631; 1668: [B4027], S2878; 1669: H2965; 1670: B4900.

- 65. (31 x 31 mm) NEWCOMB—1676: O490.

- 66. (16 x 15.5 mm) NEWCOMB—1666: H2631; 1668: C1922, E323; 1676: O476.

- 67. (33 x 32.5 mm) NEWCOMB—1677: S651.

- W

- 68. (32 x 31 mm) RAWORTH—1639: The Declinator and Protestation. NEWCOMB—1654: T2381; 1660: R1239; 1666: H2631.

- 69. (21.5 x 21.5 mm) R. RAWORTH—1647: D413. NEWCOMB—1653: A3329; 1655: [C581].

- 70. (38 x 39 mm) NEWCOMB—1676: O490. NEWCOMB JR.—1683: M1958.

- 71. (30.5 x 30 mm) NEWCOMB—1676: O490.

- 72. (16 x 15 mm) NEWCOMB—1650: L129; 1669: H2965.

- 73. (12.5 x 12 mm) NEWCOMB—1679: [B1582].

- 74. (18 x 19 mm) NEWCOMB—1674: B6311; 1676: O476, [G2177].

- 75. (23 x 21.5 mm) NEWCOMB—1658: [S646].

- Y

- 76. (31 x 31 mm) NEWCOMB—1653: M2868.

- 77. (18 x 17.5 mm) NEWCOMB—1671: [C746]; 1676: [G2177].

- 78. (34 x 34 mm) RAWORTH—1644: S2364. R. RAWORTH—1646: C826. NEWCOMB—1655: D1453; 1660: G2040; 1666: H2631; 1675: S2866(W & McM 1086, 1087). NEWCOMB JR.—1683: M1958.

- 79. (67.5 x 66.5 mm) NEWCOMB JR.—1685: C5387.

DECORATIVE INITIALS

Notes

Raworth took up his freedom in the Stationers' Company on February 6, 1632, but appears not to have opened his own shop until 1638. See H. R. Plomer, A Dictionary of Booksellers and Printers . . . 1641 to 1667 (1907), p. 152.

Numbers 46 and 53 in H. R. Plomer, English Printers' Ornaments (1924), appear to be similar to those used by Raworth and Newcomb, but Plomer offers no measurements and lists occurrences some thirty years earlier.

H. R. Plomer in his Dictionary . . . 1641 to 1667, p. 136 quotes an entry in the Stationers' Register of Apprentices to the effect that Newcomb was apprenticed to Dexter for eight years from November 8, 1641, but Newcomb's signing books in 1648 attests to the fact that he must have gained his freedom long before November of 1649. One must also disregard, as wrongly dated, the copy of Edward Reynold's Israels Prayer, "By Thomas Newcomb for R. Bostock, 1645." The volume contains Raworth ornaments and sectional titles dated 1649.

The Wing S.T.C. lists a few items which appear not to be government publications printed by Thomas Newcomb after 1688, but one cannot be certain that the phrase "Printed by Thomas Newcomb" does not mean published by Newcomb rather than printed by him.

The Cowley volume offers no evidence of the printing's having been divided between two printers. Macock was by 1688 a well established printer who would have little reason to borrow or buy the second hand ornaments of another printer, and yet among the goodly number of Macock-printed books from 1646 to 1691 which I have examined, I have found no other occurrence of either ornament.

| | ||