| Coupon bonds, and other stories | ||

PREACHING FOR SELWYN.

1. I.

MR. JERVEY'S PART OF THE STORY.

“I AM one of the keepers at the Asylum, you know.

“The Asylum stands on a hill; not much of a

hill, either, but just a pretty elevation of ground, with a

noble lawn sloping down to the river-bank, from which it

is separated by a high board fence. None of your commonplace

fences, understand, such as seem often to have

no other use than just to spoil a landscape. You would

say that, as a general thing, a fence like that about an

estate must be designed for keeping people out. This,

though, was meant to keep people in. The people, in

our case, are the inmates of the Asylum.” And Mr. Jervey

touched his forehead significantly.

“There was a wicket in the fence, that opened into a

boat-house, that opened at the other end on to the water.

There the doctor kept his boat, in which we gave the

patients many a fine row and sail. For he was one of

your right-down sensible, kind-hearted doctors; none of

your — Well, I won't draw comparisons, for fear I may be

considered wanting in respect toward his very worthy successor.

“He — I mean the old doctor — believed in the wholesome

influence of kindness and change of scene and mild

recreation on his patients. So he was always thinking of

nights, and occasionally at other times, the boat-house was

turned into a bathing-house for a certain class of patients.

Of course it was only a certain class that could be trusted

either to go on or into the water. `It always has

a good effect to trust those that can be trusted,' says

the doctor. Then, you know, the boat and the bath, and

all such things, worked well, held out as rewards for

good behavior.

“One Sunday morning, a new patient we had just got in

complained to me that he had been promised a swim in

the river, but that nothing had been said to him when the

others went in the night before. He was so very anxious

for his bath that morning, that I thought 't would do no

harm to lay his case before the doctor.

“`What do you think of him, Jervey?' says the doctor.

“`Very quiet, very gentlemanly,' says I.

“`Bring him to me,' says the doctor.

“So I went and brought Mr. Hillbright, — for that was

the man's name, — and introduced him with the little formality

usually pleasing to that kind of people.

“`Mr. Hillbright, Doctor,' says I.

“`Ah! good morning, Mr. Hillbright,' says the doctor.

`How are you this morning?'

“`Very well indeed, Doctor, I thank you kindly,' says

the patient. He was a man of about five-and-forty, well

dressed, and very gentlemanly, as I have said; belonged to

a good family; rather fleshy; a little bald on the top of

his head; but with nothing very peculiar in his appearance

except a quick way of speaking, and a quick way of dropping

his eyes before you every now and then. `Very well

indeed, Doctor,' says he; `only the sins of the world weigh

upon me very heavily, as you are aware.' And in the most

solemn manner he bowed that bald-topped head of his until

his name on it.

“`O yes, I know,' says the doctor. `They weigh upon

me too. But we shall get rid of the burden in good time,

— all in good time, Mr. Hillbright.'

“That was the doctor's style of managing patients of

this sort. It did no good to contradict them, he said, but

if you could convince one that his case was n't peculiar,

that others had had similar troubles and been cured of

'em, that was the first step toward bringing him around

to his right senses. So, if one complained that he had a

devil, the doctor would very likely relate to him in confidence

how he had had a much bigger devil, and how he

had got rid of him. `I 'm in hell! I 'm in hell, Doctor!'

says a woman to him. `I don't doubt it; a great many

people are,' says the doctor; `I have been there myself.'

And that would usually throw cold water on the fire sooner

than anything.

“Hillbright was quite taken aback by the doctor's candid

admission and expression of sympathy; for I suppose he

had never been treated with anything but contradiction

and argument till he came to us. But he rallied in a

minute and said, glib as a parrot, `I have taken the

sins of the world,' says he, `and I must bear them till

I am permited to preach and convert the world. Meanwhile

the world hates me, and all I can do for my relief

is to go down into the river and be baptized. I

need n't explain to a philosopher like you,' says he, bowing

again to the doctor, `that some of the sins will wash

off.'

“The doctor approved of the idea, and said: `Jervey,'

says he, `always have a bath-tub at Mr. Hillbright's disposal.'

“`A bath-tub?' says Hillbright, with a sort of sorrowful

ocean would n't hold them!'

“`Jervey,' says the doctor, `give the sins of the world

a good plunge into the river this morning.'

“So I took the key of the boat-house and went down

with my man to the shore.

“He had n't been long in the water when he made an

awful discovery. The sins would n't wash off! He must

have soap, and there was only one sort that would serve

his purpose. He said I would find a cake of it on the little

table in his room, and begged me to go and get it.

“I did n't like to lose sight of him; but the doctor had

told me always to humor his patients in trifling matters

which they considered important. `For even if we can't

cure 'em,' says he, `we can at least make 'em comfortable';

and going for a cake of soap was so little trouble, and besides,

as I said, Hillbright was such a quiet, respectable,

gentlemanly person, I thought him safe, especially if I

kept possession of his clothes. They were in the boat-house

locker, where I always kept the clothes of the bathers;

so I just turned the key on 'em and went for the

soap, leaving Mr. Hillbright to give the sins of the world a

good soaking till I came back.

“I had a pretty good hunt, finding nothing on his table

but a small pocket Bible, about the size and shape of the

thing I expected to find, but not the thing itself. It occurred

to me in a minute, though, that this was really

what the man wanted; for where else was the kind of

soap that would wash away the sins of the world? I

grinned a little at my own previous simplicity, but determined

that nobody else should have a chance to grin at

it, least of all my man in the water; so I took the Bible,

and says I to myself, `I 'll hand it to him as if it was

actually a cake of soap, and I had understood his subtle

with it.'

“I unlocked the little door in the fence, and entered the

boat-house, and was immediately struck by an odd look it

had, as if something strange had taken place in my absence.

The boat — yes, that was it — the boat was gone! I ran

along the narrow side of the platform to the door opening

on the river, and looked out, — about as anxiously as I

ever looked out of a door in my life: there was the river,

running smoothly, and looking as innocent of the sins of

the world, and the morning was looking as still and lovely,

as any river or any Sunday morning that ever you saw.

But there was no boat and no Hillbright to be seen;

boat, Hillbright, sins of the world, all had disappeared

together.

“I ran back to the locker, and found the man's clothes

all right. My respectable, gentlemanly patient had

launched himself into society in a surprising state of

nature, — a thing I had n't for a moment believed him

capable of doing, he was always so very distant, I may

say formal, in his deportment. What with his mystical

cake of soap, and his running away as soon as I was out

of sight, I own he had fooled me most completely.

“Now, I lay it down as a general principle that nobody

likes to be taken in, even by a man in his senses. Still

less do you fancy that sort of humiliation from a man out

of his senses. Then put the case of a person in my position,

— a keeper, supposed to have more experience and

wit in dealing with the insane than you outsiders can have,

— and you perceive how very crushing a circumstance it

must have been to me.

“I ran like a deer down the river-bank, till I came to

the bend, around which I felt sure of getting a sight of the

boat. I was right there; I found the boat, but it was

aboard. There was no Hillbright to be seen, afloat or

ashore, and it was n't possible to tell which way he had

gone, for the high fence had concealed his movements, and

then the river-banks below were fringed with trees and

bushes on both sides. So all I could do was to hurry back

to the house, give the alarm, and get all hands out on the

hunt for him, that fine Sunday morning.”

Thus far our friend Jervey.

2. II.

PARSON DODD AND THE BAY MARE.

Parson Dodd was to be that day a partner in a triangular

exchange. That is, Dodd was to preach for Selwyn,

Selwyn was to preach for Burdick, and Burdick was to

preach for Dodd.

From Dodd's parish at Coldwater to Selwyn's at Longtrot

was a distance of some fourteen miles. Just a nice

little Sunday morning's drive in fine weather; and one to

which Dodd looked forward with interest, for two or three

reasons.

To begin with, Dodd was a bachelor of full five-and-forty.

He had always intended to marry, but being one

of your procrastinating gentlemen, who make it a rule to

put off until to-morrow whatever they are not absolutely

compelled to do to-day, he had, with other things, put off

matrimony. He had even paid somewhat marked and

prolonged attentions — at different periods, of course — to

three or four ladies, each of whom had in turn been

snatched up by a more enterprising suitor, while he was

Very much as if he had been contemplating a fair morsel

on his fork, expecting in due time to swallow it, but in no

haste to do so, when some puppy had rushed in and swallowed

it for him, with a celerity that quite took the good

man's breath away.

Not that Garcey was a puppy, by any means. He was

a brother clergyman, and Selwyn's predecessor at Longtrot;

and there was a time when he liked wonderfully

well to come over and preach for Dodd. And that is the

way he became connected with the romance of Dodd's life.

To the last of the estimable ladies alluded to — namely,

Miss Melissa Wortleby, of his parish — Dodd did actually

propose matrimony, after taking about five years to think

of it. But Miss Wortleby was then aghast at an offer

which would have made her the happiest of women three

days ago.

“Dear me, Mr. Dodd!” said she. “Why did n't you

ever tell me, if you had such a thing in your mind?”

The parson stammered out that a serious step of that

nature was not to be taken in haste. “There 's always

time enough, you are aware, Miss Wortleby.”

“Yes,” said poor Miss Wortleby, with a look of distress;

“but Mr. Garcey — he — he proposed to me last Sunday,

and I —”

“You accepted him?” said Parson Dodd, turning pale

at this unexpected stroke.

Miss Wortleby's tears were a sufficient confession.

“The traitor!” said Parson Dodd. “He took advantage

of our exchange to offer himself to you. He has taken

advantage of many another exchange, I suppose, to come

over and cultivate your acquaintance. Always teasing me

for an exchange — the vil —”

“No, no, dear Mr. Dodd!” pleaded Melissa Wortleby,

had no idea, any more than I had, that you —”

“To be sure,” said Parson Dodd, resuming that serene

behavior and those just sentiments which were habitual

with him. “I have nobody to blame but myself, dear

Miss Wortleby.”

Dodd must have seen that he was really the young

lady's choice, and that it would have been no very difficult

task to prevail upon her to cancel her hasty engagement

with Garcey. But we must do him the justice to say that

if he was given to procrastination in matters of right, he

was still more slow to decide upon any course of doubtful

morality. So he stepped gracefully aside, and gave the

pair to each other in a very literal sense, himself performing

the wedding ceremony.

Garcey was settled, as I said, in what was now Selwyn's

parish; there he lived with his gentle Melissa, preached

two or three times a week (exchanging very rarely with

Dodd in those days, however), and laid the foundations of

a wide reputation and a large family. Then he died, leaving

to his afflicted widow a barrel of sermons and six children.

Melissa still lived at the parsonage over at Longtrot,

and boarded Selwyn, the young theological sprig, lately

slipped from the academical tree and planted in that parish

in the hope that he might take root there. It was

even whispered that he was likely to take root there in a

double sense, succeeding the lamented Garcey not only in

the pulpit, but also in Mrs. Garcey's affections. But of

course there was no truth in that suspicion. Parson Dodd

must have known there was no truth in it, for he would

have been the last man to serve another as poor Garcey

had served him. And somehow Dodd liked to preach for

Selwyn.

To be quite frank about the matter, Parson Dodd had

lately awakened one morning and discovered to his surprise

the marks of age creeping over him. His crown was getting

bald, his waistcoat round, his hair (what there was of

it) silvery (but he wore a wig), his frontal ivory golden.

Until yesterday he had said of growing old, as of everything

else, “Time enough for that.” But however man

may procrastinate, the old fellow with the scythe and the

forelock is always about his work; and here was Dodd's

field of life more than half mown before he knew it.

“Only a little patch of withered herbage left!” thought

he with consternation.

Of course no young lady would think of having him now.

He might have deemed his case hopeless, but there was

the mother of Garcey's innocents! I 'll not say that these

living monuments to the memory of his late friend were

not just a little dampening to the ardor of his reviving

attachment. Of all the ready-made articles with which the

world abounds, one of the least desirable is a ready made

family. To bear with easy grace a weighty domestic responsibility

(and a wife and six may be considered such),

one should begin with it at the beginning, like the man in

the fable, who, by shouldering the calf daily, came at last

to carry the ox. But to commence married life where

another man has left off, that requires courage. But Dodd

was a man of courage; one of those who, irresolute and

dilatory in ordinary matters, show unexpected pluck in the

face of formidable undertakings. He had thought of all

these things. And, as I have said, he liked to preach for

Selwyn.

Usually, when he had that privilege, he drove over to

Longtrot early in the morning, put up his horse at the parsonage,

and had a good hour with the relict of the lamented

Garcey before the ringing of the second bell. An hour

perhaps in drilling the little Garceys in their Sunday-school

lessons. Whatever the pious task, his heart was

evidently in it; for it was always noticeable afterward

when he walked to church with the widow and her little

tribe, leading the youngest between them, that his kind

face beamed with peculiar satisfaction.

But, as I have hinted, there was other cause for the

interest with which Parson Dodd looked forward to this

particular Sunday morning's ride. Shall I confess it? The

worthy man, having no family, was a lover of animals, especially

of horses, — more especially of fine horses. He had

lately exchanged nags (an act which in a layman is termed

“swapping”) and got a bay mare; to his experienced eye

a very superior beast to the one he put away. He had

as yet had no opportunity to try her paces for more than

a short spirt; but he liked the way she carried her hoofs,

and he believed her to be “sound and true.” He had her

of a townsman, — Colonel Jakes, — who, though something

of a jockey, was never known actually to lie about a horse;

and Colonel Jakes had said, as he turned the quid in his

cheek, and squinted with a professional air across the

mare's fetlocks, and looked candid as a summer's day,

“There 's lots of travel in that beast, Parson. You see

how she goes off; and it 's my experience she 's poorest at

the start. Yes, Parson, I give ye my word, you 'll find

that creatur's generally poorest at the start. You 'll say

so when you 've drove her a little.”

It was a lovely morning, and the heart of Parson Dodd

was happy in his breast, when he set off, at half past seven

o'clock, alone in his buggy, driving the bay mare, to go

over and preach for Selwyn.

He was very carefully dressed in his dark brown wig,

his suit of handsome blue-black cloth, and ruffled shirtbosom

clergymen far and near. “Let me see that coat and that

shirt-bosom anywhere, and I should know it was you,” said

Mrs. Bean, with just pride in her washing and in her minister,

that very morning. “But,” her eye resting with

some surprise on his neckcloth, “where did you git that

imbroidered new white neck-handkerchief?”

“A gift, — a gift from a lady,” replied Parson Dodd,

evasively.

He was not quite prepared to inform her that his appearance

in it foreboded a change in her housekeeping.

But so it was. In the note that came with it a few days

before, Melissa had written with a trembling hand: “I embroidered

it for my dear husband. Will you accept and

wear it?” Of course, these simple, pathetic words were

not in any way designed as a nudge to Dodd's well-known

procrastinating disposition. Yet he could not but feel that

putting on the neckcloth that morning was as good as

tying the matrimonial halter under his chin.

“Wal, I don't care, it 's perty anyhow!” said Mrs. Bean.

So Parson Dodd started off, wearing the fatal neckcloth,

and driving the bay mare. Her coat was glossy as silk;

the air was exhilarating; the birds sang sweetly; she

stepped off beautifully. He knew Melissa would be expecting

him, and he was happy.

“But hold on!” said he, pulling the rein all at once.

“Bless me, my sermon!” The bay mare and the embroidered

neckcloth had quite put that out of his head.

“If I had really gone without it, I should have had to

overhaul some of poor Garcey's,” thought he, as he wheeled

about.

He wheeled again as he drove up to the gate, and called

to Mrs. Bean to go into his study and hand him down his

sermon-case, which she would find lying on his desk. As

have n't seen how she moves off.”

“No, I ha'n't,” said Mrs. Bean.

Parson Dodd tightened the reins, — those electric conductors

through which every born driver knows how to

send magnetic intelligence, the soul of the man at one

end inspiring the soul of the horse at the other. And Parson

Dodd clucked lightly. But Queen Bess (that was the

name of her) did not move. A louder cluck, and a closer

tension of the quivering ribbons. Queen Bess merely laid

her ears back, curled down her tail as if she expected a blow,

and — Dodd could see by the sparkling black eye turned

back at him — looked vicious.

“Go 'long!” said Parson Dodd, showing the whip.

Queen Bess quietly braced herself. She was evidently

used to this sort of thing, and prepared for a struggle.

Parson Dodd saw the situation at a glance, remembered

the jockey's declaration that she was “generally poorest

at the start,” and blushed to the apex of his bald crown.

“What is the matter with him?” cried sympathetic Mrs.

Bean.

“Him 's balky, that 's what 's the matter,” replied the

irritated parson. “Go 'long, Bess, I tell you!” And he

touched her shoulder with the whip.

The touch was followed by a sharp cut; but Bess only

cringed her tail more closely, and looked wickeder than

ever. Then he tried coaxing. All to no purpose. It was

a dead balk.

Notwithstanding his burning shame at having been

shaved by a layman who “paltered with him in a double

sense,” and his wrath at the perverse brute, and his irritation

at Mrs. Bean, who always would call a mare a him,

Parson Dodd controlled his temper, and begged the lady's

pardon, but told her she had better go into the house, for

(she declares that he said “devil”), then got out of the

buggy, went to the animal's head, stroked her, patted her,

spoke gently to her, and led her out into the street.

Then he once more got up into his seat. But Queen

Bess saw through the transparent artifice; she had taken

serious offence at the indecision shown at starting, and

now she refused to start at all without leading. So Parson

Dodd got out again, gave her another start with his

hand on the bridle, then sprang back into the buggy, at

the risk of his limbs, while she was going. “I wonder if

I shall have to start in this way when I leave Melissa's?”

thought he, and wondered what people would say to see

him with a balky horse!

He let her go her own gait for a mile or two, then, by

way of experiment, stopped her, and started her again.

She seemed to have got over her miff by this time, for she

went off readily at a word. Having repeated this experiment

two or three times with encouraging success, (as if

the cunning creature did n't know perfectly well what he

was up to!) Parson Dodd began to think he had n't made

such a fatally bad bargain after all. “With careful management,

I can cure her of that trick,” thought he.

When he had made about ten miles of the journey, he

came to a stream where it was his custom always to “stop

and water” when going over to preach for Selwyn. There

was then an easy trot of four miles beyond, which he thought

well for a horse after drinking; and, besides, he considered

a little soaking good for his wheels in dry weather.

Parson Dodd got out, let down the mare's check-rein,

got into the buggy again, and, turning aside from the

bridge, drove down into the water, purposing to drive

through it and up the opposite bank, country fashion.

In mid-channel, he let Queen Bess stop and drink. She

from drinking too fast and too much, found it necessary to

pull her head up now and then. This, I suppose, vexed

her; for she was a testy creature, and could not bear to

be trifled with. At last she would not put down her head,

and, when requested to start, she would not start. In

short, Queen Bess had balked again, this time in the middle

of the stream.

Parson Dodd's lips tightened across his teeth, and his

knuckles grew white about his whip-handle. But the cringing

tail and the leering eye told him that he might spare his

blows. Madam had fully made up her mind not to budge.

The parson stood up and reconnoitred. The stream was

thigh-deep, and it was a couple of rods to either shore.

The bridge was just out of jumping distance. There was

no help within call. Parson Dodd looked at the water,

then at his neatly fitting polished boots, ruffled shirt-bosom,

and blue-black suit, grinned, and sat down again.

“Queen Bess,” said he, “you think you 've got me now.

It does look so. How long do you intend to keep me here?

Take your own time, madam! But mind, you make up

for this delay when you do start.”

It was difficult, however, for a person of even so equitable

a temper as his own to possess his soul in patience very

long under the circumstances. Suppose Queen Bess should

conclude not to start at all that forenoon? What would

Melissa think? And who would preach for Selwyn?

There was another consideration. Queen Bess had had

her fill of cold water when she was warm, — a dangerous

thing for a horse that has been driven, and that is not kept

in exercise afterward. Before many minutes, Dodd had no

doubt she would be fatally foundered; though he did not

know but the cold water about her feet might do something

toward keeping the fever from settling in them.

“This, then, is the creatur' that 's usually poorest at

starting! I should say so!” thought he. “I wish Colonel

Jakes was lashed to her back, like another Mazeppa, and

that I had the starting of her then; I 'd be willing to

sacrifice the mare. Come, come, Bess! good Queen Bess!

Will you go 'long?”

She would not, of course.

Parson Dodd looked wistfully at both banks again, and

at the inaccessible bridge, and at the hub-deep water, and

said, grimly, after a moment's profound meditation, —

“There 's only one way; I must get out and lead her!”

It is said that the brains of drowning men are lighted

at the supreme moment by a thousand vivid reflections.

Parson Dodd experienced something of this phenomenon,

even before he got into the water. He saw himself preaching

for Selwyn in unpresentable, drenched garments, — he,

the well-dressed, immaculate bachelor parson; or begging

a change of the widow, and exciting great scandal in

the congregation by entering the pulpit in a well-known

suit of Garcey's, (“'T will be said I might at least have let

his clothes alone until after I had married into them!”)

or waiting to be found where he was, at the mercy of a

vicious mare, by the first church-going teams that came

that way. Would he ever take pride in driving a neat

nag, or care to preach for Selwyn, after either of these contingencies?

“I 'll pull off my boots anyway; yes, and my coat;

there 's no use of wetting that.” He stood up on his

buggy-seat and looked anxiously both up and down the

road, and, seeing no one, said, “I may as well save my

pantaloons.” Then why not his linen and underclothes?

“The bath won't hurt me. Why did n't I think of this

before?” said he, pulling up the buggy-top for a screen.

He began with his embroidered white neckcloth, which

and pocket-book, and sermon, saying, at the same time,

“Some leisure day, Queen Bess, you and I are going to

have a settlement. Lucky for you this is n't a very favorable

time for it. I 'll break your temper, or I 'll break

your neck!”

Thus talking to the shrew, and quoting exemplary

Petruchio, he packed his clothes carefully in the wagon-bottom,

and then — laughing at the ludicrousness of the

situation, in spite of himself — stepped cautiously down

into the water.

“Aha!” said he, at the first chill: “I must give my

head a plunge, or the blood will rush into it.” So he took

off his wig and laid it in his hat. Then he ducked himself

once or twice. Then he waded to the mare's head,

took her gently by the bridle and led her out.

In going up the oozy bank from the water's edge, the

animal's plashing hoofs bespattered him with mud from

head to foot. He therefore left her on the roadside, and,

taking his handkerchief, ran back to wash and dry himself

a little before putting on his clothes.

He had cleansed himself of the mud, and was standing

on a log beside the bridge, making industrious use of his

handkerchief, when he thought he heard a wagon. Fearing

to be caught in that most unclerical condition, without

even his wig, he looked up hastily over the bridge. There

was no wagon coming, but there was one going. It was

his own. Queen Bess was deliberately walking away; for

there was a nice sense of justice in that mare, and having

refused to start when he wanted her to, it was meet that

she should balance that fault by starting when he did not

want her to. Poor Dodd had not thought of that.

Taken quite by surprise, and appalled by the horrible

possibility that presented itself to his mind, he immediately

or too mad to be frightened at the apparition of him

in the water, deeming it perhaps a device to make her “go

'long.” But now a glimpse of the unfamiliar white object

flashing after her was enough, and away she went.

“Now do thy speedy utmost,” Dodd! Remember that

your clothes are in the buggy; and think not of the stones

that bruise your feet. Ah! what a race! But it is unequal,

and it is brief. The rascally jockey said too truly,

“There 's lots of travel in that beast, Parson!” The

faster Dodd runs, the more frightened is she; and since

he failed at the first dash to grasp the flying vehicle, there

is no hope for him. He has lost his breath utterly before

she has fairly begun to run. He sees that he may as well

stop, and he stops. Broken-winded, asthmatic, gasping,

despairing, he stands, a statue of distress (or very much

like a statue, indeed), on the roadside, and watches horse

and buggy disappearing in the distance. Was ever respectable,

middle-aged, slightly corpulent, slightly bald

country parson in just such a predicament?

Melissa would certainly look in vain for his coming, that

sweet Sunday morning. And who — who would preach for

Selwyn?

3. III.

PARSON DODD'S SUNDAY-MORNING CALL.

The mere loss of horse and buggy was nothing. But O,

his clothes! Parson Dodd even hoped to see the vehicle

upset or smashed, and his garments, or at least some portion

of them, flung out on the roadside. But nothing of

the kind occurred, as far as he could see. Of all his fine

been repaired; the old shaft had been re-opened; and Guy, in

his executive capacity, had made acquaintance with that hitherto

unprofitable bore. And now was heard the sound of

sharpening the drills at the forge, and once more the mountain

resounded with the thunder of the blast. Among all the

prominent members of the association great enthusiasm prevailed.

Money was abundant, poured in as priming to the

pump which was expected soon to pour out again inexhaustible

golden supplies. Except in the coldest of the weather, the

work of the miners went on; penetrating inch by inch,

slowly and laboriously, the stubbornest azoic stone. Daily it

was anticipated that the drills would strike through, or that

the blasts would blow through, into the subterranean chambers

of coin; during which time the Biddikin mansion

glowed with warmth, and flowed with plenty, so that the

doctor grew fat, and not even poor little Job went hungry.

With the workmen at the summit, or with the men and

women of the association who filled with new magnetic life

the rooms of the old house, Guy spent his days and nights.

Here, in the half-spiritual yet intensely human elements of

a nondescript society, he found something which his soul

craved. He was much with Christina. Whether or not he

loved her, she was fast becoming necessary to him. When

he went uncomforted from Lucy, the smiles, the radiance, the

spiritual gifts, of the seeress were his consolation. Thus unconsciously

Lucy drove him to her rival. And she was forapproach.

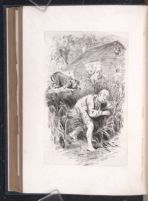

I call for help, and explain my situation.” So he advanced,

wading through the high, nodding grain, which his hands

parted before him: a wretched being, but hopeful; and

with light fancies still bubbling on the current of his darker

reflections.

“Gin a body meet a body coming through the rye,”

thought he.

A Sunday-morning stillness pervaded farm and dwelling.

A quail whistled on the edge of the field, “More wet!

more wet!” which sounded to Parson Dodd much like a

mocking allusion to his own recent passage of the river.

Glossy swallows were twittering about the eaves of the barn;

and enviable doves, happy in their feathers, were cooing

on the sunny side of the old shed-roof.

In the midst of this scene of perfect rural tranquillity,

the barn door was opened. The parson's heart beat fast;

somebody was leading out a horse. It was a woman!

A woman with a masculine straw hat on her head. She

was followed by another woman, also in a straw hat,

bringing a horse-collar. Then came a third woman, similarly

covered, carrying a harness. The horse's halter and

afterward his head were passed through the collar, which

was then turned over on his neck and pressed back against

his breast; the harness was put on and buckled; and then,

— horrible to tell! — a fourth straw-hatted woman appeared,

and held up the shafts of an old one-horse wagon,

while the other three backed the animal into them, and

hooked the traces.

“My luck!” said the parson, through teeth chattering

with excitement, if not with cold. “Not a man on the

place! All women! And there 's another somewhere.

Why did n't I think? It 's the house of the Five Sisters!”

The five Misses Wiretop, spinsters, known to all the

country round about. They were rather strong-minded,

and very strong-bodied; they kept this house, and wore

straw hats, and tilled their few ancestral acres, and dispensed

with man's assistance (except occasional aid in

seed-time and harvest), and went regularly to church, and

were very respectable.

“They are getting ready for church now,” thought Parson

Dodd. “They go to Selwyn's. I always see them there.

They are going to hear me preach!”

No doubt they would have been glad to do anything for

him that lay in their power; for though they did not

think much of men generally, they had a regard for parsons,

and for Parson Dodd in particular; he knew that

from the serious, reverential glances turned up at him ever

from the Five Sisters' pew. “Yet it is n't myself they

care for,” thought he, “it 's my cloth.” And here he was

without his cloth!

He asked himself, moreover, what they could do for him,

even if he should make his wants known to them. Of

course there were no male garments in their house; and

the most he could expect of them was an old lady's gown.

He fancied himself in that!

He reasoned, however, that these sisters and their horse

might help him to recover his garments and his mare.

So he advanced still nearer, and was about calling out to

them over the top of the grain, when the Sabbath stillness

was broken by a sharp voice, —

“Stop, you sir! Stop, there!”

He did stop, as if he had been shot at. Turning his

eyes in the direction of the voice, he saw the fifth sister,

with one sleeve of her Sunday gown on, and with one

naked arm, leaning her head out of a chamber window,

and gesticulating violently.

“Git out o' that rye! git out o' that rye! right straight

out! Do you hear, you sir? Do you hear?”

Parson Dodd must have been deaf not to have heard.

But how could he obey? Instead of getting out of the

rye, he crouched down in it until only the shining top of his

bald crown was visible, like a saucer turned up in the sun.

“Madam!” he shouted back, “I beg of you —”

But the sharp voice interrupted him: “Don't you know

no better? Can't a poor woman raise her little patch of

rye, but some creatur' must come tramp, tramp through

it? Don't you know what a path is for? There 's the

lane; why did n't you come up the lane?”

Poor Dodd would have been only too glad to explain

why. But now rose a clamor of female voices, as the four

sisters at the barn ran down to the end of the house, between

it and the field, to learn what was the matter.

“In the rye!” said the sister at the window, pointing.

“Some creatur' tryin' to hide, — don't ye see him? Looks

like a man. What ye want? Why don't ye come out?

Scroochin' down there! Who be ye, anyhow?”

“Ladies,” said poor Dodd, putting up his chin timidly,

and looking over the grain with a very piteous expression,

“don't you know me?”

But that was a very absurd question. Certainly they

did not know him without his wig. Where were those

wavy brown locks, which looked so interesting in the

preacher's desk, especially to the female portion of his congregation?

Could any one be expected to recognize in

that shorn and polished pate the noble head and front of

the bachelor parson? No, he must proclaim himself.

“Ladies! good friends! don't be alarmed, I entreat. I

have met with a —”

He was going to say misfortune. But just then he met

with something else, which interrupted him.

The Five Sisters kept, as a protection to their loneliness,

a very large dog. One of them, learning that there was a

creatur' in the rye, had, before learning what that creatur'

was, whistled for Bruce. Bruce had come. He perceived

a rustling, or caught a gleam of the inverted saucer, and

made a dash at the field, leaping upon the dilapidated boundary-wall.

His deafening yelps from that moment drowned

every other sound. He could n't be called off even by her

who had set him on. Terror at the sight of a naked man

(few sights are more terrifying to an unsophisticated dog)

rendered him wholly wild and unmanageable. There he

stood on the wall, formidable, bristling with rage and

fright, and intercepting every word of the poor, gasping

wretch in the grain with his furious barking.

I am very sorry to say that Dodd was about as badly

frightened as the dog. He crouched, shrank away, and

finally retreated, the brute howling and yelping after

him, and the exasperated spinsters screaming to him to

take the path, and not trample down the rye, — did n't he

know what a path was for?

So ended Parson Dodd's Sunday-morning call on the

Five Sisters.

4. IV.

MR. HILLBRIGHT SETS OFF ON HIS MISSION.

When Mr. Hillbright sent our friend Jervey for the

mythical soap, it is by no means certain that he contemplated

escaping from the Asylum. I think, if we could

hear Hillbright's part of the story, it would be something

like this: —

He had detected the turning of the key in the boat-house

had found that his clothes were locked up. What was that

for? To prevent him from putting them on, of course,

and walking off in his keeper's absence.

“They fear I will walk off, do they? Then I will walk

off!”

Such, very probably, was his brief train of reasoning;

and such, very certainly, the conclusion arrived at. Should

the trifling want of a few rags of clothing stand in the way

of a great resolution? Should he who bore the sins of the

world, and whose duty it was to go forth and preach and

convert the world, neglect such an opening as this to get

out and fulfil his mission?

“Providence will clothe me!” And, indeed, it looked

as if Providence meant to do something of the kind. “Behold!”

There was a long piece of carpet, very ancient

and faded, in the bottom of the boat; he pulled it up,

wrapped it fantastically about him, and was clad.

He then pushed the boat out into the river, giving it an

impulse which sent it across to the opposite shore. Then

he leaped out, leaving it adrift on the current. When Mr.

Jervey found it below the bend, Mr. Hillbright was already

walking, with great dignity, in his improvised blanket,

across the skirts of a neighboring woodland, like a sachem

in his native wilds.

He had not gone far before he began to experience great

tenderness in the soles of his feet. Then by degrees it

dawned upon him that the loose ends of the carpet flapping

about his calves were but a poor substitute for trousers;

and that his attire was, on the whole, imperfect. “Too

simple for the age,” thought he. Picturesque, but hardly

the thing in which to appear and proclaim his mission to

a fastidious modern society. Would the world, that refused

to tolerate him dressed as a gentleman, accept him

Islands?

He tried various methods of wreathing the folds of antique

tapestry about his person; all of which seemed open

to criticism. He was beginning to think Providence might

have done better by him, when, getting over a fence, he

found himself on the public highway.

He knew he would be followed by his friends at the

Asylum; and here he accordingly stopped to take an observation.

He was near the summit of a long hill. At the

foot of it, near half a mile off, he saw a horse coming at a

fast gallop, which to his suspicious mind suggested pursuit,

and he shrank back into some bushes to remain concealed

while it passed.

As the animal ascended the slope, the gallop relaxed to

a leisurely canter, the canter declined to a trot, and, long

before the summit was attained, the trot had become a

walk. The horse had no rider, but there was a buggy at

its heels. Arrived near the spot where Hillbright was hid,

it turned up on the roadside, and put down its head to nip

grass. Then Hillbright saw that there was nobody in the

buggy. The horse was a runaway, that had been stopped

by the long stretch of rising ground. The horse, I may

as well add, was a bay mare.

“Providence is all right,” said Hillbright, emerging from

the bushes. “This is for my sore feet.”

At sight of the strange figure, grotesque in faded scroll

patterns of flowing tapestry, the mare shied, and would

have got away, but a two-mile course, with a hill at the

end of it, had tamed her spirit. So she merely sprang to

a corner of the fence, and remained an easy capture.

As Hillbright was about setting foot into the vehicle, —

for he had no doubt of its having been sent expressly that

he might ride, — he found an odd heap of things in his

and, following up that interesting clew, he drew forth a

pair of pantaloons; with them came a coat and waistcoat,

all of handsome blue-black cloth. “Providence means that

I shall be well clothed,” was his happy reflection, as, exploring

still further, he discovered boots and underclothes,

and a shirt of fine linen, with a wonderfully refulgent ruffled

bosom. With a triumphant smile, he proceeded to put

the things on, and found them an excellent fit.

There was still a hat left, freighted and ballasted with

various valuables, uppermost among which was a luxuriant

chestnut-brown wig. Now, Hillbright had never worn a

wig. But since he had borne the sins of the world, the

top of his head had become bare, and was not here a plain

indication that it ought to be covered? He accepted the

augury, and put on the wig.

Next came a richly embroidered white neckerchief, for

which he also found its appropriate use. Then in the

bottom of the hat remained a gold watch, which he cheerfully

put into his fob; a plump porte-monnaie which he

pocketed with a smile; and a thin package of manuscripts

betwixt dainty morocco covers, which, untying its neat

pink ribbons, he proceeded to examine.

The miracle was complete. The package was a sermon.

“This is all direct from Heaven!” said Hillbright, delighted,

and having no more doubt of the truth of his

surmise than if he had seen the buggy and its contents let

down in a golden cloud from the sky.

Thinking to find room for the package in the broad

breast-pocket of his coat, he discovered an obstacle, which

he removed. It proved to be a little oval pocket-mirror.

He held it up before him, and had reason to be pleased

with the flattering account it gave of himself. The graceful

blue-black suit became him wonderfully well; they made

a new man of him. Had he known Dodd of Coldwater, he

would almost have taken himself for that well-got-up bachelor

parson.

Then for the hat, which was a stylish black beaver,

somewhat the worse for its ride; giving it a little needful

polishing before putting it on, he noticed a letter protruding

from the lining. He opened it and read:—

“Reverend and dear Sir: — We have made all the arrangements.

The Ex. is all right. You preach for Selwyn at

Longtrot, on Sunday, the 7th.

This seemed plain enough to the gratified Hillbright.

“We” he understood to mean his unseen friendly guardians.

The “arrangements” they had made were, so far

as he could see, excellent; he was provided with everything!

The “Ex.” undoubtedly alluded to his exit from

the Asylum; and that was certainly “all right.” To-day

was Sunday, the 7th; and here was his work all laid

out for him. Who Selwyn was, and where Longtrot was,

he did not know; but doubtless it would be revealed.

The signature of the missive puzzled him at first; but

soon a happy interpretation occurred to him. It was

evidently no signature at all, but an injunction. “B. B.”

stood for “Be! Be!” and it signified, “Be a man! Be

a great man! Be thyself! BE HILLBRIGHT!”

Yet when he came to scrutinize the address of the letter,

he perceived that the name of Hillbright, against which

the world had conceived an unreasonable prejudice, was to

be dropped for a season. “It appears,” said he, “I am to

be known as Dodd, — E. Dodd, — Rev. E. Dodd. I don't

see what the E. stands for. I wonder what my first

name is?”

So saying, he stepped into the buggy, gathered up the

reins from the dasher, put under his feet the carpet that

was lately on his back, and set off grandly on his grand

mission.

The bay mare was herself again; she did not balk.

5. V.

JAKES IN PURSUIT.

Among the officers sent out in pursuit of the fugitive

from the Asylum was the superintendent of the Asylum

farm, a stout, red-faced man, named Jakes, — a brother,

by the way, of our friend Colonel Jakes of Coldwater.

He took with him an Irish laborer named Collins, also a

strong rope with which to bind, and a coarse farmer's suit

with which to clothe, the madman when caught.

The superintendent and his man put a horse before a

light carryall, and had a fine time driving about on the

pleasant country roads, while others of the pursuing party

scoured fields and woods on foot. At last they struck the

Longtrot road, and turned off toward Coldwater.

They had not driven far in that direction before they

saw a man coming in a buggy.

“A minister, ye may know by his white choker,” observed

Collins.

“You 're right, Patrick,” said Jakes, “and I vow, I

believe I know who he is! I know that bay mare,

anyhow. She 's a brute my brother over in Coldwater got

shaved on by a travelling jockey; and he told me last

week, with a grin on one side of his face, he had put her

off on the minister. I bet my head that 's Parson Dodd!

Jakes reined up on the roadside. “Have you seen — have

you met — hold on, if you please, sir — a minute!”

Thus appealed to, the stranger stopped his horse.

Superintendent Jakes thought that face was somehow

familiar, and so thought Collins. In fact, they had seen

it more than once about the Asylum grounds, within a

few days, as the owner of the said face knew very well.

But since one sometimes fails to recognize old friends

in strange circumstances, it is no wonder that these

farmers did not identify the new patient in Dodd's

clothes.

“We 're looking for a crazy man that got away from the

Asylum this morning,” said Jakes. “A man about five feet

nine or ten. Rather portly. Good-looking and gentlemanly

when dressed; but he ran off naked. Have you

seen or heard of such a man?”

“I have n't seen anybody crazier than you or I,” said

the supposed parson.

This sounded so much like a joke, thought uttered very

gravely, that Jakes was tempted to speak of the bay

mare.

“I think I know that beast you 're driving. You had

her of Colonel Jakes of Coldwater, did n't you? Well,

he 's my brother. Your name is Dodd, I believe.”

“I have been called Dodd. But can you tell me what

my first name is? It begins with E,” said the driver of

the bay mare, with a shrewd, almost a cunning look, which

did not strike Jakes as being very ministerial. Yet he had

heard that Dodd was something of a joker.

“I never heard you called anything but Parson Dodd.

Yes, I have too. You made a speech at the convention;

I read it in the paper. E stands for Ebenezer.”

“Thank you,” said the other. “I 'm glad I 've found

his eyes on the ground.

“How do you find the mare?” said Jakes, by way of

retort.

“Perfect; arrangements all perfect.”

“That so? No bad tricks? Of course she 's all right;

glad you find her so,” grinned Jakes.

“How far is it to Longtrot?” asked the counterfeit Dodd.

“About a mile 'n' a half — two mile — depends upon

where in Longtrot you 're going.”

“Do you know Selwyn?”

“Minister Selwyn, preacher in the yaller meetin'-house?

I don't know him, but I know of him. How does she

start off?”

“You shall see.”

The bay mare started off very well; and the fugitive

from the Asylum, having obtained from his pursuer rather

more valuable information than he gave in return, disappeared

over the crest of the hill, on his way to the “yaller

meetin'-house” in Longtrot.

“Wonder if she re'lly ha'n't balked with him yet?” said

Superintendent Jakes, as he drove on. “I guess he 's a

jolly sort of parson. I 've seen him somewhere, sure 's the

world, though I can't remember where.”

“You have, and I was there,” said Collins; “though

where it was, I remember no more than yourself.”

They made inquiries for the fugitive all along the route,

but could hear of no more extraordinary circumstance, that

Sunday morning, than a runaway horse, seen by one or

two families, as it passed on the road to Longtrot.

“It must have gone by before we turned the corner,”

said Jakes, “for we 've seen no nag but the parson's.”

At last they came in sight of a little red-painted house,

standing well back from the street. “This is the home of

'em a call.”

He turned up the lane, driving between the house and

the rye-field, and stopped in front of the wood-shed. The

dog, still bristling from his recent excitement, gave a surly

bark, and went growling away. At the same time, five

vivacious female faces appeared, three in the doorway and

two at an open window, and “set up such cackling” (as

Jakes ungallantly expressed it) that he could “hardly hear

himself think.”

“Is this Mr. Jakes?” cried one.

“From the Asylum?” cried another.

“I told you so, sister! I told you so!” cried a third.

“I knowed the man was —” cried a fourth.

“Crazy!” cried the fifth, and all together.

“Dog Bruce chased him out of the rye —”

“Sneaked off behind the fences —”

“Over toward Neighbor Lapham's —”

“An' sister Delia declares —”

“Hush, hush, sister!”

“Yes, I will! She declares she believes he had n't a

rag o' clothin' to his back!”

“Thank you,” said Jakes, having got all the information

he wanted almost without the asking. “He 's my man!

Thank ye, sisters! Good morning.”

6. VI.

THE WIDOW GARCEY.

At the bay-window of the pretty Gothic parsonage in

Longtrot sat the widow of the late pastor. She was

dressed in voluminous black, exceedingly becoming to her

“sighing and grief” had not produced on her precisely the

effect of which Falstaff complained, it had not certainly

wasted her to a shadow. No wonder if the contemplation

of those generous proportions, of those cheeks still fair and

round, and of the serene temper that served to keep them

so, had persuaded Parson Dodd that there might be something

yet left for him in the future better than the lonely

life he was living.

There was a book in the fair hand that had embroidered

the white neckcloth “for her dear husband.” It was that

absorbing poem of Pollok's, “The Course of Time,” which

she justly deemed not too lively for Sunday reading. Her

serious large eyes were fixed on its pages, except when

ever and anon they glanced restlessly over it, out of the

window and down the pleasant, shady street, as if in expectation

of somebody quite as interesting as the poet

Pollok. Somebody who did not make his appearance,

driving down betwixt the overhanging elms, past the

church-green, and up to the gate of the parsonage, as in

fancy she saw him so plainly whenever her eyes were on

the book. Why did they look up at all, since it was only

to refute the pretty vision?

Poor Melissa sat there until she seemed living the

Course of Time, instead of reading it. Occasionally she

varied the direction of her glances by looking at her

watch; and she grew more and more troubled as she saw

the hour slipping irrevocably by which the husband's

friend should have given to comforting the fatherless and

widow that Sunday morning.

“What can have happened?” she asked herself. “He

must have taken offence at something! What have I said

or done? It must be the cravat! Why did I do so foolish

a thing as send it with a note?” She could have

write it!

The first bell rang. And now people were going to

church. The children were teasing to start. They were

tired of sitting still in the house. What was she waiting

for? Was that old Dodd coming again to-day?

“Levi! never let me hear you call him old Dodd again!

Mr. Dodd is still a young man, and he has been a good

friend to your poor mother. There!” she exclaimed, with

a little start, for her eyes, wandering down the street again,

saw the long-expected buggy coming at last.

It was a peculiar buggy, high in the springs, and with a

high and narrow top. She could not mistake it. She was

equally sure of the stylish hat and wavy brown locks and

ample shirt-frill of the driver. But in an instant the thrill

of hope the sight inspired changed to a chill of disappointment

and dismay. Parson Dodd did not drive on to the

parsonage, as he had always done before, when coming to

preach for Selwyn. The buggy turned up to the meeting-house,

and disappeared in the direction of the horse-sheds.

She waited awhile, in deep distress of mind, to see it

or its owner reappear; but in vain.

“Levi,” she said, “go right over to the church, and see

if Mr. Dodd has come. Go as quick as you can, but don't

let anybody know I sent you.”

It seemed to her that the boy was never so provokingly

slow in executing an errand.

At last she saw him returning leisurely, watching the

orioles in the elms, while her heart was bursting with impatience.

She signalled him from the window, and lifted

interrogating brows at him. Levi grinned and nodded

vivaciously in reply. Yes, the minister had come.

“Are you — are you very sure?” she tremblingly inquired,

meeting him at the door.

“A'n't I!” said the lad. “Did n't I first go and look at

his buggy under the shed? He 's got a new horse; but I

guess I ought to know that buggy, often as it 's been in our

barn. Then I peeked in through the door, and saw him

just going up into the desk.”

Poor Mrs. Garcey was now quite ready to go to church.

Since Dodd would not come to her, she must go to him;

she must see his face, and get one look from him, even if

across the space that separated pulpit from pew.

“How was he looking, Levi?” she asked.

“Kind o' queer. I always thought Dodd felt big enough,

but I never saw him carry his head quite so high. Looked

as if he was mad at something.”

“O, I must have offended him!” sighed the unhappy

Melissa, putting on her things.

With slow and decorous steps she marshalled forth her

little tribe from the gate of the parsonage across the green

to the church-porch. The bell was ringing again, its brown

back just visible in the high belfry, tumbling and rolling

like a porpoise in the waves of its own sound. Wagons

were arriving, and the usual throng of church-goers were

alighting on the platform or walking up the steps. In the

vestibule she found a group of friends inquiring seriously

concerning each other's health, and in suppressed voices

talking of the latest news. There seemed to be some excitement

with regard to an insane man who had that morning

escaped from the Asylum, whom nobody appeared to

have seen, though he had been heard of by several through

those who were out in pursuit of him. Somehow, Melissa

took not much interest in the greetings and the gossip of

these worthy people, and parting from them, she passed

on into the aisle.

“Poor dear! She can't forgit him,” whispered kind-hearted

Mrs. Allgood, with a tear of sympathy gathering

figure.

“Huh! she 's thinkin' of another husband a'ready!”

answered sharp-tongued Miss Lynx, with a toss.

It cannot be denied that of the two, Miss Lynx had the

clearer perception of the hard fact in the case. Yet as she

set it forth, unclothed by grace and the warm tissues of

human sympathy, it was no more the truth than a skeleton

is a living body; and Mrs. Allgood's gentler judgment

was more just. Melissa had not forgotten that good man,

Garcey; and if now, in her loneliness and bereavement,

she cherished hope of other companionship, was it for

tart Miss Lynx to condemn her? Nay, who, without

knowledge of the human heart, and compassion for its sufferings

and its needs, had even a right to judge her?

She passed down the aisle, preceded by her little ones

(the elder of whom, by the way, were beginning to be not

so very little), and followed them into the pew in which she

had first sat when a bride. She would have been alone in

it then, but for the two or three poor persons to whom

she was always glad to give seats. But one after another

a little Garcey had appeared, first in her arms, perhaps,

then in the seat beside her, and thus, year by year, the

family row had increased, until now it almost filled the

cushioned slip. A mist of tender, regretful sentiment

seemed to suffuse the very atmosphere about her as she

listened to the tone of the bell, and thought what changes

had come over her dream of life since she first sat there

and looked up with pride to see the beloved, the eloquent

— her Garcey — in the desk! Now, here she was again,

looking with anxious eyes and a troubled heart for another.

There were the well-known wavy chestnut-brown locks,

and a shoulder of the blue-black coat, just visible from the

deign to look at her. He held his head bowed behind the

desk, as if in devout contemplation, and thoughts in which

she, alas! had no share. She longed to see him lift it,

and turn toward her those gracious, sympathizing features,

the very sight of which was a comfort to her heart. And

it must be confessed she had a strong curiosity regarding

the embroidered cravat.

“I must speak with him after the service,” thought she.

“I will make him come to the house.” And she turned

and whispered to the topmost head of the little row.

“It has just occurred to me, Levi, you 'd better go and

put his horse in our barn. It will be too bad to have the

poor beast standing under the shed all day.”

“'T won't hurt anything; besides, he might have drove

over there himself, if he wanted his horse put out,” said

Levi, with a scowl.

“You can get into the buggy and ride over,” said his

mother, grown all at once wonderfully solicitous with regard

to the welfare of the poor beast.

The ride was an object, and Levi went.

The bell stopped ringing, the choir ceased singing, the

congregation was in its place, all hushed and expectant;

and still Levi did not return. His mother would have felt

anxious about him at any other time; but now a greater

trouble absorbed the less.

It was not like Parson Dodd to sit so long in that way

with his head down. A movement of the arm, and a rustle

of leaves heard in the stillness of the house, showed that

he was turning over the manuscript of his sermon, or selecting

hymns, or looking up chapter and verse. But all

that should have been done before. He ought not now to

keep the people waiting.

The silence was broken by a cough. This was followed

suppressed. Then entered four of the Five Sisters, uncommonly

late this morning, for some reason. In spite of

untoward circumstances, they had come to hear Mr. Dodd

— that dear, good man — preach. And now a buzz of

whispers began to run through the congregation; hushed,

however, as soon as the preacher rose.

Melissa, watching intently, saw the noble head of luxuriant

chestnut-brown hair slowly lifted. Then bloomed

the abundant shirt-ruffle over the desk, together with —

yes, the white neckerchief embroidered by her own hand!

But even while she recognized it, a thrill of amazement, a

chill of consternation, passed over her, as the wearer,

stretching forth his hands, cried out in a loud, strange

voice, —

“We will pray for the sins of the world!”

7. VII.

FARMER LAPHAM'S EXPLOIT.

When Parson Dodd withdrew from the society of the

Five Sisters and their dog Bruce, he descried across the

fields a house and barn situated on another road, and

made toward them, under the shelter of walls and fences,

thinking that if he could take them in the rear, and enter

the barn unperceived, he might at least secure a horse-blanket

in which to introduce himself to the family.

He found, however, to his dismay, that they must be

finally approached across a range of barren pasture, unsheltered

even by a shrub. No friendly rye-field here;

and he was too far off to make known his wants by shouting.

cow-house in which he took refuge, but timidly, and without

the desired effect. What was to be done?

He had turned aside to visit the cow-house, in the feeble

hope of finding there some relief to his forlorn condition.

But it was empty even of straw.

As he cast about him in his despair, seeking for something

wherewith to cover his farther advance, his eye fell

upon the cow-house door. “If I only had that off its

hinges, I might carry it before me,” thought he. He took

hold of it and found it could be easily removed. In a

minute he had it in his arms. “Samson carrying off the

gates of Gaza!” was the lively comparison that occurred

to him, — but with this difference: whereas, in familiar

Bible pictures, the strong man was represented as bearing

his burden on his back, this modern Samson poised his

upon his portly bosom. “Circumstances alter cases,”

thought he.

With arms stretched across it, grasping its edges with

his hands, and just lifting it from the ground (it was not

very heavy), he moved forward with it cautiously, — much

like a Roman soldier under cover of his immense scutum,

or door-shaped shield, occasionally setting it down to rest

(being careful at such times to take his toes from under

it), or reconnoitring his ground from behind it; but always

keeping it skilfully betwixt his person and the enemy's

walls.

Now, one can easily picture the amazement of the worthy

Lapham family, when its younger members reported a

wonderful phenomenon in the cow-pasture, that calm Sunday

morning; and mother and children running to look,

behold! there was the cow-house door advancing in this

extraordinary manner to pay them a visit; staggering

slightly, and balancing itself occasionally on its lower corners,

the art of walking! Close scrutiny might perhaps have

revealed to them the human fingers clasping the edges of

it; or the feet of flesh and blood taking short steps under

it; or the glistening crown of the bearer peeping furtively

from behind. But when the vulgar mind is greatly astonished,

it is prone to see only that which most astonishes;

and, accordingly, good Mrs. Lapham and the little Laphams,

failing to discriminate in such trifling matters as

hands and feet, saw only the gross phenomenon of the

perambulating door. It was like Birnam Wood coming to

Dunsinane.

What gave a sort of dramatic effect to the apparition

was the grotesque outline of a human figure, large as life,

which the boys had chalked on the outside of the door, for

a target. As soon as they saw this advance, grinning at

them, they were greatly excited; and one ran for the

gun.

“Keep back, mother!” said he; “I 'll give the old

thing a shot, if 't is Sunday!”

“Stop! You sha' n't, Jason! Martin, run for your

father! Run!”

Mr. Lapham had been talking with a stranger at the

gate, who had just driven up when the children ran out to

proclaim the wonder.

“Nonsense, children!” said he. “A door don't move

across the country without somebody to help it; you ought

to know that, mother. Wal! there!” he exclaimed, witnessing

the miracle from the kitchen window. “It is on

its travels, sure enough! Jason, run and see if you can

catch that man I was talking with. Holler! scream! Be

quick!”

“Who is he, father?” asked mother.

“A man from the Asylum — says one of their crazy folks

behind that door, I 'll bet a dollar!”

This seemed a very plausible explanation of the mystery;

but it did not serve to tranquillize the mother and

children. Was not a live madman as much to be dreaded

as a walking door?

“Don't be frightened. Just shet the house and keep

dark. I 'll head him off. Give me the gun, I may want

it.” And arming himself, out the farmer sallied.

Parson Dodd had by this time perceived that his approach

was creating a sensation. For want of a pocket,

he had tied his handkerchief to his wrist. He now fluttered

that white flag over a corner of the door for a signal;

then, with his hand behind his mouth for a trumpet, summoned

a parley. Looking to see some friendly recognition

of his flag of truce, great was his consternation at beholding

so warlike a demonstration as a man running to the

ambush of some quince-bushes with a gun. In vain he

fluttered his white flag, and called for help.

“I a'n't goin' to fall into no trap sot by a crazy pate!”

thought shrewd Farmer Lapham, as he concealed himself.

Poor Dodd was in a terrible situation. He could not

advance without the risk of receiving a bullet; neither

could he lay the door down, unless, indeed, he first laid

himself down, and then drew it over him for a blanket.

He might retreat, but that movement, too, presented difficulties.

So there he stood, holding up the target, beckoning

and shouting himself hoarse to no purpose.

And now the musical clamor of church bells rose on the

tranquil morning air. “The wedding-guest here beat his

breast, for he heard the loud bassoon!” thought he; for still

he could not keep odd fancies out of his brain. Yet how

far off those bells sounded! — not in distance only; they

seemed to be in a world of which he had once dreamed.

day as something he might have written in a previous

state of existence, something quite foreign to the dread

realities of life.

“I can't stand here holding up a door forever!” thought

he at last. And he determined to move on, in spite of

bullets. So he took up the door, and resumed his march.

Observing the point he was aiming at, Lapham thought

it wise to get into the barn before him, and station himself

where he could keep guard over his property, watch the

supposed madman, and fire a defensive shot if necessary.

Dodd, bearing up the door, did not perceive this flank

movement; but advancing to within a few yards of the

barn, he was astonished at hearing a voice thunder forth

from a window, “Stop, or I 'll shoot!”

Dodd stopped and peeped forth from behind his portable

screen, showing a bald crown which was very much against

him.

“His keeper said he was bald on top of his head,” the

farmer reasoned. And he called out, “What do you

want?”

“Rest and a guide and food and fire,” was running in

Dodd's mind; but he answered in plain prose, and very

emphatically, “I want clothes.”

This was another corroborating circumstance, and a very

strong one.

“How came you here without clothes?”

“I lost them by a singular accident. I am a clergyman,

on my way to preach.”

This was conclusive. “The very chap! His keeper said

he imagined himself a preacher,” thought the farmer.

“Wonder if I can't manage to trap him!” And he cast

about him for the means.

“I 'll explain everything; only give me something to

cover myself, and don't keep me standing here!” said Parson

Dodd, growing impatient.

By this time Lapham had formed his plan. “Do just

as I tell ye now, and you shall have clothes. Come into

the barn, turn to the right, and you 'll find a harness-room,

and in it you 'll find a frock and overalls. Do you hear?”

Dodd heard, and the prospect of even so poor a covering

thrilled his heart with gratitude. He came on with

his door, left it leaning against the barn, and entered.

He found the harness-room as described, and seized

eagerly upon the frock and overalls. But just as he was

putting them on the door of the room flew together with a

bang; the crafty farmer, who had hidden behind it, sprang

and turned the key, and the “madman” was locked in.

Having accomplished this daring feat, Farmer Lapham,

deaf to the cries of his victim, ran out excitedly to call for

help, just as Patrick Collins was taking down a pair of

bars on the other side of the pasture for Superintendent

Jakes to drive through. Their errand was soon made

known.

“I 've ketched the feller for ye!” cried the elated

farmer. And he led Jakes to the dungeon within which

the entrapped parson was calling lustily.

“Unlock the door; don't be afraid, man!” said Jakes.

Lapham opened it and stepped cautiously back while

the superintendent entered, followed by Collins with a

rope and a bundle of clothes.

Within stood the captive, a comical figure, in loose blue

frock and overalls, barefoot and wigless, and with a countenance

in which indignation at the farmer, joy at the

prospect of deliverance, and a consciousness of his own

ludicrous situation, were mingled in an expression which

was very droll indeed.

“How are you?” said Jakes in an offhand way. “We

have brought your clothes; would you like to put 'em on?”

“I would; and I am infinitely obliged to you, my good

friends!” said poor Dodd, thinking the worst of his

troubles now over. “How did you find — But what —

These — these are not my clothes!”

“A'n't they?” said Jakes. “You 'd better put 'em on,

though. They 'll do till you get back to the doctor's.”

“To the doctor's? What do you mean? I am a clergyman.

I was on my way to preach —”

“Yes, we understand all about that. Come, on with

the clothes. We don't expect you 'll give us any trouble,

Mr. Hillbright.”

“Hillbright! I am Dodd, — Dodd of Coldwater, — a

minister!”

“There are two of you, then!” said Jakes, laughing

incredulously. “We just met one Parson Dodd, in his

buggy, driving the bay mare he had of my brother, going

over to preach at Longtrot. He 's there by this time.”

“Dodd — Longtrot — the bay mare!” gasped out the

astonished parson. “Impossible!”

“Come, no nonsense, Mr. Hillbright! Colonel Jakes,

of Coldwater, is my brother, and I know the mare perfectly

well, — the balky brute!”

“There is some mistake here, Mr. Jakes, — if that is

your name. I knew the Colonel had a brother at the Insane

Asylum, and I suspect you are he.”

“Yes, and you 've seen me there often enough, I suppose.

Now, no more fooling. I don't want to use force,

if it can be avoided; but you must go with us, — that 's all

there is about it. Collins, pass along that rope.”

“Never mind the rope,” said Dodd. “Just hear my

explanation, and you 'll save yourself and me some trouble.

That mare balked with me in the middle of the river, and

in the wagon, and she ran away with them.”

“A very ingenious story,” said Jakes; “but you

would n't have thought on 't if I had n't just said she was

a balky brute. Come, this won't do. Mr. Hillbright, or

Mr. Dodd, or whatever your name, you must go with us;

and you can take your choice, whether to go peaceably or

be tied with this rope. We 're much obliged to you, Mr.

Lapham.”

Seeing resistance to be vain, Parson Dodd stepped into

the wagon, stared at by the whole family of Laphams, who

had come out to get a view of the madman, and was carried

off triumphantly by Jakes and Collins.

8. VIII.

DÉNOUEMENT.

Animated by the prospect of a ride, young Levi Garcey

backed the minister's buggy out from under the shed, got

up into it, took the reins, and was having his simple reward,

when, as he was crossing the street, a slight misunderstanding

occurred between him and the bay mare. She

wanted to return homeward, never yet having enjoyed the

hospitalities of the Garcey stable. Not being permitted

to follow her own sweet will, she refused to move at all, —

balked, in short. And this was the reason why Levi did

not go back into church.

There he was in the middle of the street, when a man

in a chaise drove up. He was the same who had stopped

at Farmer Lapham's gate, and whom Jason Lapham had

failed to overtake. To be more explicit, it was Jervey.

Stopping to help the boy out of his trouble, or to make

inquiries concerning Hillbright, he remarked in the bottom

of the buggy something that had a familiar look. He

pulled it up, and recognized the strip of carpet belonging

to the doctor's boat.

“How came this thing here?”

“I d'n' know. I found it in the buggy.”

“Whose buggy is it?”

“The minister's, — Mr. Dodd's.”

“Where is he?”

“In the meetin'-house, where I ought to be,” said Levi.

“Just look out for my horse a minute,” said Jervey.

And he started for the church door, rightly regarding the

carpet as a clew which might lead to something.

What it did lead to was the most astonishing thing that

ever happened in all his remarkable experience. He had

thought that, if he could get a word with the minister, he

might perhaps hear from Hillbright, and lo! the minister

was Hillbright himself! He did not recognize him at first

in that wonderful costume, which seemed little short of

miraculous; and he could scarcely credit his senses when

the madman's phraseology and tones of voice (he was still

praying at a furious rate for the sins of the world) betrayed

his identity.

The prayer was an incoherent outpouring of mingled

sense and nonsense; and the congregation was beginning

to show marked signs of uneasiness and excitement under

it.