The prisoner of the border a tale of 1838 |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. |

| 30. |

| 31. |

| 32. |

| 33. |

| 34. |

| 35. |

| 36. |

| 37. |

| 38. |

| 39. |

| 40. |

| 41. |

| 42. |

| 43. |

| 44. |

| 45. |

| 46. |

| 47. | CHAPTER XLVII.

ROUGH VISITORS. |

| 48. |

| CHAPTER XLVII.

ROUGH VISITORS. The prisoner of the border | ||

47. CHAPTER XLVII.

ROUGH VISITORS.

Immediately before the carriage stopped, Gordon, who was

driving, observed that they passed a man who was slowly approaching

the jail, bearing some light burden, and who, in fact

was a domestic in the family of the keeper. He approached the

vehicle when it became stationary, and, without speaking, stood

looking at it for some moments, much to the alarm of the driver,

who feared that he might discover its occupants, although the

windows were closed.

Gordon hesitated a moment as to the proper course to pursue,

but as it was important to gain time, and he expected Johnson's

appearance momentarily at the front door, he remained silent as

long as the reconnoiterer did not speak. He did speak soon,

however, and inquired in a careless way whom the carriage belonged

to.

Gordon replied,

“It's a livery-stable hack, and I've come for a Yankee that I

brought here early in the evening. He's some friend of the poor

fellow that's going to swing to-morrow.”

“Oh, yes,” drawled the man, sauntering a little nearer, and

looking attentively at the coach and horses.

“You've seen this Vrail, I suppose,” Gordon continued, thinking

to engage his attention, so as to keep him from looking into the

carriage.

“Oh, yes, I've seen 'em all. I've seen eleven hung. Twice I

saw three strung up at a time. There's only to be one to-morrow;

that's nothing.”

“Do you mean to see it?”

“Yes.”

The fellow, whose proximity to the carriage had become in the

highest degree alarming, started suddenly at this point of the

conversation, as if he had seen or heard something which surprised

him, and if he had uttered a word indicating suspicion, or

had started to go into the house, Gordon had resolved to leap

down and seize him at all hazards, and to secure his silence by

threats or by force. But the man instantly resumed the conversation,

quite in his previous manner, and after continuing it a

little while, he turned slowly about, and walked on his way toward

a gate which led to a back entrance into the building.

Gordon was in a most painful state of indecision, since to stop

him forcibly might cause an alarm which would prove fatal to

their project, while if his suspicions had been excited, it was

equally dangerous, nay, far more so, to allow him to proceed.

But believing that his own fears had deceived him, he chose what

he thought to be the least risk, and allowed the man to depart.

As he went, however, he called to him, asking him if he would

inform the gentleman inside that his carriage was ready and

waiting. The man replied in the affirmative, but quickened his

step as he did so, and instantly disappeared through the gateway.

Had Gordon seen his changed manner then, he would have known

how great was the cause for alarm. Darting quickly forward, he

entered a basement door, and hurriedly inquired for the jailer,

and when informed that he was in the main hall, he hastened up

stairs, and to the side of his employer, to whom he said in a loud

whisper,

“There's something looks wrong outside, sir; a carriage quite

full of men, all very still, and the driver is a Yankee, I know by

that he is waiting for this man. It may be all right, but it ain't

a livery-stable `turn-out,' I know, for it is too stylish for that.”

The alarmed jailer cast a hurried look of suspicion on the

pretended lawyer, and then suddenly called out to the men in the

hall,

“Don't open the front door, but step around the back way and

see. There may be another Theller plot here.”

An electric-like light flashed from the outlaw's eyes, and his

frame seemed to dilate and tower while the hasty alarm was

spoken, but ere the words were ended, he leapt almost at a single

bound, to the door, turned back the huge bolts with the key,

which remained inside, and swung wide the massive portal.

“Now, my boys!” he shouted, “quick, for your lives!”

The carriage-door, though closed, had been left unfastened, to

admit of instantaneous egress when the signal should be given,

and instantly at the call, four men leaped out, three of whom, together

with Gordon, rushed up the steps and into the hall. Yet

quickly as they came, Johnson was attacked on all sides before

they reached him, but he stood with his back against the opened

door, only solicitous to keep it unclosed until his comrades came,

and regardless of the blows he received in maintaining his post.

The mêlée instantly became general, but the keepers had no fire-arms,

and the outlaw's party used none, so that the contest was

one only of physical strength, in which no fatal wounds were

like to be received. In numbers the opponents were equal, for

the terrified servant had fled at the first onset of the assailants,

chiefly from fear, but also for the purpose of giving the alarm, and

bringing more aid to his master.

If the belligerents were numerically equal, however, they were

far from being so in strength, for Johnson, when roused, was

quite a match for two ordinary men, and his own followers had

been chosen for their great muscular power, as well as their cour

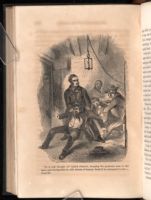

"It is well thought of," replied Johnson, dragging the prostrate man to the door, and shoving him in, with threats of instant death if he attempted to rise—Page 359.

[Description: 463EAF. Image of Johnson dragging a prostrate man towards the door. Two men are fighting just behind them while shocked patrons look on from the background shadows. There is a large hanging light in the center of the image, which highlights Johnson's angry face.]

for any one to encounter. Brom, much to his chagrin, had been

left in charge of the horses, and he found sufficient employment in

restraining the restive animals, which were frightened by the

tumult, from running away.

It was not enough, however, for the assailants that they could

master their opponents, unless they could do it very speedily, and

make good their escape with their prize, for a few minutes, at the

most, would suffice to bring a powerful addition to the enemy,

which no strength of theirs could oppose. Unfortunately it takes

many words to tell what really occurred in a few seconds of time.

No sooner did the leader see his friends at his side, than he called

to them each to engage his man, and setting the example, he

knocked the nearest down, and was hesitating how to keep him

so, when he heard the voice of Vrail, who had shuffled himself

along to the doorway of the room in which he had been left.

“Draw him in here,” he said, “and drive in the rest, if possible.

We can lock them in; there is no time to bind them.”

“It is well thought of,” replied Johnson, dragging the prostrate

man to the door, and shoving him in, with threats of instant death

if he attempted to rise.

Gordon was scarcely behind him with another fallen foe, and

Van Vrank, who had attacked the jailer himself, pushed him

rapidly backwards to the door, and thrust him in, yet standing, but

tumbling over his prostrate companions as he entered.

“Lock it now—we can quickly deal with the others!” shouted

Johnson, and the door was immediately closed and fastened, and

the key removed.

The two remaining men, who had thus far fought well and

maintained their ground, did not longer keep up the unequal contest,

but threatened by a suddenly drawn pistol in the hands of

Gordon, which he did not mean to use, they both turned and fled.

Scarcely had they done so, when the herculean Johnson caught

The remainder of the party instantly followed, and as

every man knew his post, no time was lost in taking places. Van

Vrank and another followed Johnson into the carriage, one climbed

with Gordon to the box, and Brom, after resigning the reins, got

up behind. The driver's call to his horses was lost in the louder

shout of alarm which was already resounding through the building,

but the steeds felt the tightening reins and the crackling

thong, and they started forward at an encouraging, though far

from their greatest speed. It was too dark to admit of a headlong

velocity, when an accident might prove so fatal to their

hopes, and Gordon rather restrained than urged his mettled

chargers, while as yet there was no actual pursuit. Within the

vehicle all was excitement. Johnson, on his knees before Vrail,

was busily engaged, with tools brought for that purpose, in breaking

the lock which fastened the fetters upon his ankles. Under

his skillful blows they soon fell clanking to the floor of the coach,

and Harry, in ecstasy, exclaimed,

“Is it possible that I have the free use of my limbs once more,

and that I am outside of a prison? I cannot realize all this—it

seems like some wild, bright dream.”

“Ay, you are outside of a prison, and behind a pair of fleet

horses, too,” replied Johnson; “yet it seems to me we are not

going over fast. I say, Gordon,” he continued, addressing the

latter through the open window, “are these your twelve mile

horses? What is the matter?”

“Nothing is the matter,” replied Gordon. “Would you have

a quiet party of ladies and gentlemen, on their way to Col.

B—'s party, go dashing through the streets like mad? We

don't want to raise an alarm, you know, as long as we are not

chased. Besides, it's unsafe to go faster in this darkness.”

A church-bell, which seemed to be very near them, rang out at

that instant a loud and startling peal, like that which usually

heard, crying indistinctly in the distance.

“That means us,” said Gordon, cracking his whip, and urging

his horses into a quicker pace; “now we'll show you what we

can do.”

By this time another bell began to respond to the first, and a

third and fourth almost instantly joined the clangor, while the

tumult and shouts in the streets rapidly increased.

“They will send a party of horse after us if they know which

way we have gone,” said Johnson. “Can't your span do a little

better than that?”

“Yes, they can do a great deal better when it becomes necessary,”

replied the imperturbable Gordon.

“It is necessary now,” returned the outlaw, with a suddenly

changed air. “Put them to their utmost speed this instant, I

command you, and keep them so until we reach the boats, or until

they drop!”

Gordon complied without reply. Indeed, his whole attention

was required, for the road over which his flying chariot was passing,

and with which, of course, he was not familiar, although he

had travelled it twice that day.

“If we break down,” continued Johnson, addressing his friends

inside, “the horses must be cut loose, when they will easily carry

two apiece, and the rest must follow as best they can; or, if the

horses themselves should fail, we must all take to our feet across

the fields and to the river. They are really coming,” he said, as

the increased and nearer sound of pursuit was distinctly heard.

“How could they so soon organize a force and get upon our track?”

“You forget that one man fled and gave the alarm at the

moment of your first irruption into the jail,” replied Vrail. “It

does not take long to call out a Canadian police.”

“I fear we have something worse than a police behind us. It

does not take long to call out a British troop of horse. The fire-bells

cause of alarm has been quickly spread by shouts and cries. It is

well that we are out of the city.”

“Harik! that certainly was the report of a musket,” said Van

Vrank.

“It was fired to frighten us, then,” replied Vrail; “they are

certainly too far off to see us, much less to do us any harm, and

they will not gain upon us while we go at this rate.”

“It is best not to make too sure,” answered Johnson; “we

may have to sell our lives yet for what they will fetch. I think

I am good for three men at least. But we forget, Vrail, that you

and I are both unarmed. Where are our pistols?”

“They are here, all ready to speak for themselves,” said Van

Vrank, producing a couple of brace from the seat of the carriage

which he was occupying. Each took his weapons, and while

doing so, a voice was heard through the back window of the

vehicle.

“Better hand over one or two dem pop-guns out here, Massa

Harry. I shall be de fust man 'tacked, and I got nothing to fight

with but a rope and a gag.”

“You shall have them, if necessary, Brom,” said Johnson;

“keep cool, and don't get frightened. Do you see any lights

down the road?”

“No, Massa; but I hear a gun, and think I hear a officer call

`Forward!' bery loud.”

“I think Gordon could get a little more `go' out of these

horses,” said Van Vrank, though we are certainly travelling very

fast.”

“I wish he could,” answered Johnson; “for it is not enough

that we reach the boats ahead of our pursuers; we must be far

enough from shore when they come up to be out of the reach of

their guns. But I fear to urge Gordon too far, for I can't deny

that he knows far more about horses than I do.”

“Another gun! and another! Do you hear that? What

can it mean?”

“It is sheer folly if it is meant to intimidate us. It only shows

us where they are, and enables us better to escape them. There

is another!”

At this moment the headlong velocity of the carriage suddenly

subsided into a moderate speed of six or seven miles to the hour,

and those within hurriedly inquired the cause.

“We are approaching a turnpike gate,” replied Gordon, “where

they will be sure to suspect something wrong if we come up so

fast, and they may shut down the gates.”

“That, then, is what the shots are for,” said Vrail quickly; “to

give the alarm to the gate-keeper.”

“Aha! is that the game? Go on then, Gordon!” shouted the

outlaw; “faster! faster than ever! I have the tickets here

which will carry us through.”

As he spoke he thrust one arm out of the side window of the

carriage, and held a pistol, pointing to the ground, but ready for

instant use. With all their former speed, and more, they dashed

forward and approached the gate, with a momentum that had well

nigh precipitated the horses against it before they could be

checked. It was shut, and the keeper, lantern in hand, stood

beside it, while his wife and three or four children were assembled

in the doorway, attracted by the extraordinary arrival.

“What's the matter? What's the matter? What's all this

firing?” said the man, without offering to perform his usual

office.

“Step this way, and I will tell you,” replied Johnson coolly.

The man came near the door, when he was suddenly seized by

the outlaw with one hand, while with the other he presented a

pistol to his breast.

“Bid your wife open the gate instantly, or you are a dead

man.”

His terrific voice reached the trembling woman, who did not

wait the bidding of her husband to pull up the gate, and give

free passage to so dangerous a customer.

“I was jis goin' to get down and open it myself,” said Brom,

as the carriage again rattled on, “but he won't give me a chance

to do nuffin.”

The delay had been brief, but it was sufficient to considerably

lessen the distance of the pursuers from the flying party, and the

incident would also serve, unfortunately, to make them more certain

they were on the right track.

It was no longer necessary to listen closely to hear the sound

of pursuit. A cavalry gallop makes itself audible a long way,

and the enemy was certainly not very far behind the fugitives, and

was momentarily gaining on them. Gordon's boasted team had

doubtless accomplished all that he had claimed, on his first trial

of them, but that was done by the full light of day, and with a

load materially less than that which they were now drawing. He

had great difficulty now in keeping them at a speed which he

estimated at ten miles an hour, and so pantingly was even this

task performed, that he feared to urge them beyond it, lest they

should altogether break down. But, on the other hand, far more

than half their brief journey was already accomplished, and if

they could maintain even their present rate of progress for the

remaining distance, there was no danger of being overtaken,

unless it might be by some of the random shots of the foe.

All hearts grew sanguine of reaching the boats in safety, but

many fears were entertained lest they should not be able to obtain

a secure “offing” before the arrival of the enemy on the beach.

“There will be nine of us to go in the boats,” said Johnson,

and we all know how little speed we can make with a loaded

skiff. At the best, we shall be within musket shot of the shore

for many minutes, unless Captain — has ventured the steamboat

far nearer the land than we have any reason to hope.”

“Do you think our pursuers are dragoons?” inquired Vrail.

“Certainly, judging from the musket reports which we have

already heard, and we know that there are several companies of

dragoons now in Kingston. Doubtless this is a detachment of

them.”

“If we are to be exposed for several minutes to the fire of all

their guns, we can scarcely hope to escape.”

“It looks doubtful, certainly—but we must hope for the best.

It is too dark for any certain aim, and those who are not rowing

must lie on the bottom of the boats. The oarsmen, of course, must

be exposed.”

“And at that post we may all be shot down in turn,” interposed

Van Vrank.

“Dat are is a fact, Massa Johnson and gemmen, what Massa

Garret tells you,” said the negro, who, with head partly protruded

through the rear window, had listened to the conversation; “we

shall all be shot down like crows off a dry tree. Now, you jis

listen to me; I haven't done nuffin' yet for Massa Harry, 'cept

hold the hosses at de jail, and I ain't satisfied. I can drive hosses

too, jes as well as Massa Gordon, 'zactly. Now, what you gwine

to do with these horses and carriage when you go to the boats—

leave em to the inimy, ain't you?”

“Of course,” answered Harry, who knew Brom too well to

doubt that he had something important to say.

“Bery well—you all get out quietly when we get near the boats,

and Brom will drive on a mile or so furder, and all de sogers will

follow me—don't you see?”

“Capital!” exclaimed Johnson.

“And when dey come most up to me, I jump off and run across

lots to de river, and back to de same place, where you can send a

boat for me.”

“Brom, you are certainly a noble fellow, and your stratagem is

worthy of a wiser head. I have no doubt of its perfect success for

will do all we can to bring you off afterwards.”

“I take de risk, Massa Johnson, not for you, but for Massa Harry.

I know what I'm doin'—I take de risk.”

“If my life alone were at stake, my good friend,” said Harry,

addressing the negro, “I should hesitate long before accepting

your generous offer; but I do not feel at liberty to refuse it now.

I believe we shall be able to save you. Certainly we will not

desert you, while the shadow of a hope remains.

The carriage had proceeded with undiminished speed during

this conversation, and they were now within a minute's drive of

their stopping place, which minute was devoted to giving some

directions to Brom, and to concerting a signal by which he should

indicate his position on the coast when the boat should be sent for

him. The call of the screech owl, which he knew well how to imitate,

and which is not an unusual sound in a Canadian forest, was

agreed upon for this purpose.

Near two tall maples, which partly overshadowed the road, the

carriage stopped, and when the noise of its motion had ceased,

the sound of the galloping troop behind was more distinctly

heard, and seemed frightfully near. All instantly alighted, and

Brom, hastily climbing to the vacated seat of Gordon, drove

immediately off more rapidly for the lightening of the carriage,

and with a flourish of the whip, and an encouraging cry to the

steeds, which was intended not so much for the animals, as to

attract the attention of the foe.

Vrail and his friends, elated to exhilaration by the new aspect

of affairs, clambered quickly and silently over the roadside fence,

and ran across a vacant field which alone interposed between them

and the river, where, to their inexpressible joy, they found their

boats waiting, ready for instantaneous flight.

No word of inquiry or of congratulation was spoken; all was

understood, as the running fugitives leaped into the boats, and the

silently to their task.

In less than a minute, with emotions it would be impossible to

portray, they heard the galloping dragoons dash past on the highway,

and then for the first time they knew that they were safe—

safe from the utter ruin which had impended over them, and free

as the chainless waters across whose calm surface they were

gliding towards a land of freedom. Harry was rescued! The

horrible gallows, with all its attendant terrors, had passed from

before his mental vision, which for so many weeks it had not ceased

to haunt by day and night, and never again was its fearful shadow

to fall upon his young heart.

With what exultation was that heart now beating; with what

boundless gratitude to the great Deliverer; with what inexpressible

thankfulness to the heroic friends at his side; with what tender

and melting emotions towards her whose agents they were, and

who in turn was but the agent of Heaven, in accomplishing his

deliverance.

Five minutes' rowing brought them within sight of the steamboat,

upon the deck of which Gertrude, and Ruth, and Thomas

Vrail were awaiting, with distressing solicitude, the return of the

boats. Three boisterous cheers, which rang far and wide across

the still water, announced to them the perfect success of their

approaching friends, and Gertrude, overcome with the sudden

transport of joy, was carried, swooning, below. Ruth danced, and

clapped her hands in glee, while the large tears rolled unheeded

down her cheeks, and Thomas sent back an answering shout which

spoke his own delight, and imparted new rapture to the heart of

his affectionate brother.

These spontaneous greetings were the result of irrepressible

feelings, which had rendered all parties momentarily oblivious of

the prudence which should still have influenced their actions.

One of their number was yet on Canadian soil, and the chance of

shouts of triumph, if they should unfortunately reach the enemy's

ears. But elated by so great success, it was no longer possible for

the triumphant party to feel apprehension, and as soon as they

had reached the steamboat, one of the skiffs, manned by two

volunteers, of whom Gordon was one, returned in pursuit of Brom.

To depict the scenes which, meanwhile, followed the arrival of

Harry upon the vessel's deck, and to portray the emotions with

which he and Gertrude met, would be a task in which the most

graphic pen would fail, or, if successful, would still be outstripped

by the imagination of the intelligent reader.

But unutterable as was the joy of each, it could not be complete

until they knew that the generous and devoted servant, who

had so nobly risked his life for his friends, was safe. Nor was

this addition to their pleasure long denied them. The negro was

readily found, by means of the signal which had been agreed

upon, and was brought off without difficulty, exulting almost to

madness in his success. He had decoyed the enemy about a mile

and a half beyond the place of embarkation, and had only quitted

the carriage when he plainly heard the musket-balls whistling

past him.

“I tought it time to go den,” he said, “'kase I knew Massa

Harry must be safe enough den, so I jis jump off, and hit de nigh

horse a tremendious whack, which kept 'em going a good while

yet as fast as ever. De dragoons warn't more'n fifty rods behind,

and so I jis climbed over de fence, and laid down mighty still

until dey gallop pass, and den I up and run like a wild Injun,

right straight for de river.”

“Were you followed?”

“No, sir—nobody seed me; dey all went on chasing de carriage.

Besides, 'twas berry dark, and Massa Gordon says I'm so

black I can't be seen after sundown. Ha! ha! I glad of it dis

time.”

“What did you do when you reached the river?”

“I run right on down stream until I tought I got about to de

right place, and den I climb a tree, and screech every little

while.”

“What did you climb a tree for?”

“'Kase de owls allers screech in de trees; dey don't come and

sit down on de ground and screech.”

“Oh, very true. And you did not have to wait long?”

“Oh, no; 'twan't long afore I heard de oars, and den I come

down and wade out to meet de boats.”

Brom found himself a great hero when he reached the steamboat,

and he was astonished to learn how highly his services were

estimated. He did not seem to think he had done anything very

wonderful, and his delight was not a little allayed by the reflection

that the beautiful carriage and horses, which had cost so

much money, had been lost. If he could only have brought them

off, his satisfaction would have been complete.

| CHAPTER XLVII.

ROUGH VISITORS. The prisoner of the border | ||