The prisoner of the border a tale of 1838 |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. |

| 30. |

| 31. | CHAPTER XXXI.

AN UNLUCKY WALK. |

| 32. |

| 33. |

| 34. |

| 35. |

| 36. |

| 37. |

| 38. |

| 39. |

| 40. |

| 41. |

| 42. |

| 43. |

| 44. |

| 45. |

| 46. |

| 47. |

| 48. |

| CHAPTER XXXI.

AN UNLUCKY WALK. The prisoner of the border | ||

31. CHAPTER XXXI.

AN UNLUCKY WALK.

Daylight dispelled the horrors of distempered dreams, only to

supplant them with more dreadful realities. It was a day of military

executions, and Gertrude did not escape the knowledge of the

appalling deeds which were taking place around her, and which

were reflected in painful significance from every face she encountered.

The streets were thronged with a mob of the lower classes,

gathering to witness the fearful tragedy which was soon to be enacted,

and, alas! how often yet to be repeated!

She understood now why it was that Mr. Strong had proposed

to call upon her, on that morning, for further conference, instead

of requesting her to visit him at his place of business, which for a

lady would have been almost an impossible undertaking, and she

appreciated, too, the kind consideration which had foreborne to

allude to the cause of so marked a departure from professional

habits.

He came to find Gertrude prostrated with painful excitement,

yet rallying at his approach, and stimulated to fresh exertion for

her friend by the very terrors she had been obliged to contemplate.

There was little in the interview that needs to be narrated.

The lawyer had some further inquiries and some suggestions to

make, but he dealt out as sparingly as ever to his distressed client

words to catch the meaning of each oracular sentence, and how

skillfully she extracted from them the most auspicious interpretation

they could be made to bear! How, when he was gone, she

tried to recall the exact words in which his views had been expressed,

and the very tone and look which had given them significance,

ingeniously arguing herself into the belief that he entertained

a greater hope than he revealed to her!

The day wore heavily away, for having wisely confided all preparations

for the trial to the able barrister, there was nothing that

she could do, excepting to await in painful inaction that great event.

Van Vrank paid a second visit to the prisoner in the afternoon,

and during his absence, which was unexpectedly prolonged, Gertrude

remembered that she had omitted to make a certain suggestion

to Mr. Strong which she thought it might be important to

bring early to his mind, and she looked anxiously and often for

Garret's return, in order that he might accompany her to the lawyer's

office. The streets had become comparatively quiet, although

there were still many passing, but there was no throng that could

prevent them being easily traversed by a lady under the escort of

a gentleman. But Garret did not come, and Getty grew more and

more impatient. As she went again and again to the window to

watch for his approach, she observed that the number of passers

still diminished in the streets, that there were more well dressed

people, and occasionally a pair of ladies unaccompanied by a gentleman,

and she began to contemplate venturing out with no other

attendant than Ruth. She would have engaged a carriage, but she

could not brook the delay which she had learned by experience

that such a step would occasion. It was not a long walk to the

barrister's office, which adjoined his house, and they both were

familiar with the way; and while Gertrude yet hesitated, Ruth

herself proposed that they should go, and with her usual impulsive

action, was almost instantly arrayed to start.

“We shall meet Mr. Van Vrank, I know,” she said; “and if we

don't, it is no matter. The sun is an hour high.”

They went, and so slight was the obstruction in the streets that

Gertrude soon forgot her apprehensions, and under the refreshing

effects of a walk in the open air, she even obtained a momentary

respite from her more absorbing grief. When however, they had

turned into another street, she became uneasy at observing that it

was less quiet than the one they, had left, and that occasional sounds

of wassail and revelling were to be heard from some of the lower

inns and drinking-shops which they were compelled to pass.

Groups of men of rough exterior were standing on grocery stoops,

and at the corners of the streets, noisily discussing the revolting

scenes of the day, and others whom they met, in boisterous parties

of two or three, gave similar evidence of having been witnesses

of the same fearful spectacle.

Gertrude and Ruth quickened their steps, for having accomplished

more than half their journey, it was easier to proceed than

to return, and the evil neighborhood seemed to be of but brief extent.

A little further on, the street bore a more respectable aspect,

and it improved in the distance into a genteel and fashionable vicinity,

but before attaining these promising precints, there were several

blocks to be passed, and a vacant lot of considerable extent.

While hastening to get past these dreaded localities, Gertrude's

alarm was greatly increased by observing that they were followed

by two men, who, without attempting to overtake them, seemed to

keep at a uniform distance in their rear. It might be accident, she

knew; indeed she believed it was, and rapidly as she and Ruth had

been walking, they still increased their speed, but only to find, to

their great alarm, that their followers also walked faster than

before.

Miss Van Kleeck looked in every direction for some one to

whom she could appeal for help in case of necessity, but she saw

no one near them in the garb of gentlemen, and she was just try

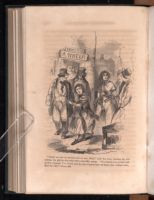

"Tain't no use to scream, nor to run, Ruth," said the man, rushing up, and seizing the girl by the wrist with a vice-like grasp. "I've found you at last, and pretty company I've found you in, too—I know how all these fine clothes come. Ha! ha! ha!"—Page 289.

[Description: 463EAF. Image of Ruth being grabbed from behind by a violent looking man in a grimy top hat. Ruth is stepping away from him towards the reader with a look of terror on her face. There are people walking among them on the street, but no one is paying attention to Ruth.]

groundless, when the elder and shorter of their pursuers stepped

suddenly in front of them, and peered into the face of Ruth.

Screaming and springing backwards, the terrified child attempted

to run, yet clinging to Gertrude, whom she tried to drag with her.

“Tain't no use to scream, nor to run, Ruth,” said the man, rushing

up, and seizing the girl by the wrist with a vice-like grasp.

“I've found you at last, and pretty company I've found you in, too

—I know how all these fine clothes come. Ha! ha! ha!”

Ruth was so utterly overcome with fright at the sight of the

abhorred man who had so long been her master and tyrant, under

the name of relative, and her mind so readily fell back into its accustomed

thraldom, that she could not articulate a word. In any

other presence or power, however great, she could have said something

in self-vindication, but here was the man who from her earliest

infancy had controlled and subjugated her will, and whose very

voice and eye seemed to have power to re-impose upon her those

mental fetters which she had temporarily thrown off.

Gertrude, indeed, spoke for her friend, as soon as her great

terror permitted, but her faint voice was lost amid the jeers of a

mob which had gathered quickly around to witness the unusual

sport.

“You can go, if you want to,” said Shay; “I don't want

nothin' of you; though you ought to be took up, if rights was

done.”

Placing Ruth between himself and his companion as he spoke,

they attempted to march off with her, but the poor child having

recovered a little vitality, struggled violently, and called piteously

on Gertrude for aid.

“Oh, will no one help us?” exclaimed Miss Van Kleeck, flitting

around the outside of the circle of men and boys interposed between

her and her late companion; “is there no good man here

to save the child?”

“What's the row?” inquired one of a pair of shabby-genteel

young men, with cigars in their mouths, who came up at the moment

and stopped near to Gertrude.

“Oh, sir, they are carrying off a little girl; they have no right

to her, I assure you. Won't you please to stop them?”

“Hallo there!” shouted one of the men, “let that girl alone,

won't you? Joe run around to the station and call a police officer

—we'll see about this”

“It's all right, Jem,” said another, addressing the would-be

philanthropist; “it's his daughter, and she ran away, and this

one is”—

A wink finished the sentence, and the man, after staring a few

seconds rudely at Gertrude, passed on heedless of her protestations.”

Shay and his assistant, in the meantime, had succeeded in starting

with their prisoner, whom they half dragged, half carried a

few steps, followed by the rabble, and by the almost swooning

young lady.

“Bring her in here,” said a burly, red-faced man, who had stood

in the doorway of his own grocery, watching the fracas, and who

now thought he could turn it to his own account, by getting the

crowd into his shop; “bring her in here, and let's have the whole

story.”

The mob poured into the groggery, nothing loth, completely

filling it, and Shay at once began to explain his conduct, which

was in substance as follows: The girl, he said, was his niece, but

that she in fact had always been the same as his daughter, as she

had lived with him since her infancy, and her parents were both

dead. She had been enticed away from his house by one of those

piratical Yankees who was to be tried and hung in a few days.

How she came here, he did not know, but he supposed after the

man's arrest she had fallen in with bad women, who had brought

her here.

The grocery keeper said she ought to be ashamed of herself,

and a dozen others said the same, and whatever Ruth had to

say was lost in the clinking of glasses and decanters which followed.

Shay and his companions treated pretty freely, and altogether

a Bedlamite confusion was soon produced, during which

the child became mute, despairing, and motionless.

Gertrude had not waited to hear the speech of Shay, for she

saw that she could neither get into the room, nor be listened to

if she did. As a last hope, therefore, she ran up the street with

great rapidity towards the residence of Mr. Strong, hoping she

might get there in time to bring him to the rescue of her

friend.

From the moment that Ruth found herself in the power of her

soi-disant uncle, and deserted by Miss Van Kleeck, utter despair

took possession of her mind, benumbing all her faculties, and

rendering her incapable of any serious resistance to her persecutor's

designs. She felt certain that she was doomed to a return

to her former dreadful state of bondage, the horrors of which she

shuddered to contemplate, and that the late magical change in

her condition, with all its dazzling hopes for the future, was

to pass away like a dream forever. Without a struggle, for

struggles she had seen to be useless, she accompanied Shay to his

lodgings at a second-rate hotel in an obscure quarter of the town,

and she heard without reply the harsh invectives which he bestowed

upon her by the way. It was even with something like

a sense of guilt that she listened to her tyrant, so great was his

influence over her, and so accustomed had she been to be told,

from her infancy, that she was perverse and wicked. He told her

now, what he had often said before, and what she feared was true,

that she had been given to him by her parents before their death,

and that he had the same lawful power over her until she came of

age, which her own father would have had, if living. There was no

law, he said, which could take her from him, and certainly no

to do it without the help of the law.

The case looked too strong for hope, and so Ruth gave it up,

and thought the sooner it was all over, and she was back again to

feel the worst of what she had to endure, the better.

She soon learned there was to be no delay in sending her

home. Shay could not, indeed, himself leave the city, because

he was compelled to remain as a witness in the approaching trial

of Vrail. But Hull, the man who had assisted in capturing the

child, was a neighbor of his, who having come to town on business

of his own, had been induced to take part in the rare sport

which had resulted so successfully, and was now made willing, by

a slight compensation, to hasten his departure for home, in order

to secure the trophy of his own and his friend's valor. For Shay

had had a glimpse of Ruth's late protector, the heavy-fisted Garret,

and notwithstanding his assumed confidence of retaining his

prize, he preferred not to come in conflict with the young man.

It had been, indeed, while Ruth was walking with him and Gertrude

on the previous day, that Shay had first discovered and

recognized her, and he had been carefully watching, with his ally,

ever since for an opportunity to meet her unaccompanied by so

formidable a champion. Gertrude's presence alone had almost

deterred him from his design, for guilt is always cowardly; but he

feared so good an opportunity might not again occur, and trusting

to the favorable locality in which he was enabled to encounter

his victim, and to the promptness of his measures for removing

her beyond reach, he resolved on the attempt.

The inn at which he had taken lodgings, and to which he had

conducted Ruth, was not many rods distant from the steamboat

landing, and he remained with his friend and their trembling

prisoner in his room until a little before five o'clock in the afternoon,

which was the stated time for the vessel to start, when they

set out together for the boat. Ruth, of course, had no baggage,

take in his hand, when the more wary Shay, beckoning to a stout,

broad-shouldered porter at the door, placed the box in his

charge.

“It is to go to the steamboat,” he said, “and we want you to

keep close by us until we get on board. I will see you paid.”

He added something in a low tone, which did not reach Ruth's

ear.

“Oh, if that's the case,” said the porter, “you had better let

me call Joe, the ostler; he's a jolly fellow for a row, and he'll be

glad to go.”

“Let him come along, though I don't think there'll be any

trouble, for they'll be safe aboard in five minutes, and in ten more

the steamer will be under way.”

Joe was called, however, and grinning with satisfaction at the

implied compliment to his prowess, he took hold of one end of the

small trunk, of which the porter held the other, and the two, carrying

their light load like some plaything between them, followed

close on the steps of the travellers. Ruth did not suspect that

they were a guard for her, and having no longer any hope, their

presence, fortunately, gave her no additional apprehension. She

submitted passively to all the requirements of her master, walking

faster or slower, as directed by him, and even trying to remember

some messages which he bade her deliver to his wife when she

arrived at home. But the hated vision of that home rose before

her as he spoke, and with it came the sweet remembrance of all

which she had lost, renewing her agitation, and increasing it

almost to madness; but she was hurried rapidly along, amidst a

crowd which thickened as they approached the wharf, among

carriages, and carts, and porters staggering under heavy loads,

all hastening to the landing, where the ready vessel was adding

to and outsounding all the din with the noise of discharging

steam.

| CHAPTER XXXI.

AN UNLUCKY WALK. The prisoner of the border | ||