The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| VI. |

| VI. 1. |

| VI. 2. |

| VI. 3. |

| VI. 4. |

| VI. 5. |

| VI.6. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

ARTICLE 10

On arson and the compensation payable therefor.[62]

1. If someone sets fire at night to somebody's property, and

ignites the house of a free man (or of a serf) he is bound, first of all,

to pay a fine according to the rank of the person and make restitution

for all of the buildings; and whatever he sets on fire there,

furnishings and equipment, he will have to restore. And with all

free men who have escaped from said fire without their clothes on,

he will have to settle according to their wound money; in the case of

women, however, this will have to be doubled. Moreover, for the

roof of the house, he will have to settle with a fine of 40 shillings.

2. And in the case of the barn[63]

of a free man, if it is enclosed

with walls and provided with a lockable bar, he will have to settle

for the roof with a fine of 12 shillings; if, however, it is unenclosed,

what the Bajuvarians call a scof,[64]

i.e., a shed without any walls, he

will have to settle with a fine of 6 shillings.

In the case of such a granary, however, as they call a parc,[65]

he

will have to settle with a fine of 4 shillings.

But in the case of a mita,[66]

if he un-roofs it or sets it on fire, he

will have to settle with a fine of 3 shillings.

But in the case of a smaller one, which they call a scopar,[67]

he

will have to settle with a payment of 1 shilling.

And everything he will have to restore in like.

3. In the case of smaller buildings, if someone devastates them,

or tears their roofs down, as often happens, or surrenders them to

fire, which they call firstfalli,[68]

he will have to settle for every one

which is separately built, such as a bathhouse, a bakehouse, a

kitchen house, or any other structure of this sort, with a fine of 3

shillings and will have to restore whatever is destroyed or burned

down.

4. However, if he sets fire to a house so that it bursts into flame

yet the house does not burn down and is saved by the members of

the household, he will have to settle the wound money for each of

the free people, because he inunwan[69]

them, as they say, i.e., put

them in fear of their life, and beyond that he will not have to make

any further compensations in excess of that which has been consumed

by the fire.

The fines forfeited to the duke, however, remain unaffected.

And if he wishes to contest any of these he will have to defend

himself with a champion or must take an oath supported by 12

oath helpers.

As far as the serfs are concerned the destruction of a house

(firstfalli) will have to be settled in like manner as the cutting off of

a hand.

5. And now, since we deem our ruling on the burning of buildings

completed, it is not inappropriate that we explore in greater

detail the fines imposed upon the destruction of the living quarters

of a household.

6. If someone with criminal or any other intent, through arrogance

or hostility, through negligence or a certain lack of understanding,

tears down the roof of a free man, he will have to settle

with a fine of 40 shillings.

7. If [he tears down] that post by which the ridge is held in place

and which they call firstsul ("ridge post"), he will have to settle

with a fine of 12 shillings.

8. If he tears down in the interior of the building that post which

they call winchilsul ("corner post"),[70]

he will have to settle with a

fine of 6 shillings.

9. For the other posts of this order, however, he will have to

settle with a fine of 3 shillings.

10. But for the corner posts of the outer order he will have to

settle with a fine of 3 shillings.

11. For all the other posts of this order he will have to settle, for

each individually, with 1 shilling.

12. For the tie beams,[71]

however, he will have to settle each with

a fine of 3 shillings.

13. For the outer beams, however, which we call spanga[72]

[literally,

"clamp"] because they hold together the order of the walls,

he will have to settle with a fine of 3 shillings.

14. For everything else, however, that is the boards,[73]

the

shingles,[74]

and the bracing-struts,[75]

or whatever else is used in the

construction of a building, he will have to settle with 1 shilling each.

And if a person has inflicted all of this damage to the building

of another person, he shall not be compelled to pay more than what

is due for the destruction of the roof and whatever crimes he has

committed greater than this. Minor infractions of this person are

not to be prosecuted with the exception of those for which restitution

has to be made according to law.

The article then goes on to define the compensation set

for damage to the yard, the braided wattle enclosures, the

pastures, roads, and pathways.

Of all surviving literary sources on early medieval architecture

this article of the Lex Bajuvariorum offers the

fullest and most detailed information on the nature of

contemporary domestic building. In the first place it

confirms what had already been demonstrated by the Lex

Alamannorum, namely, the fact that the West Germanic

farmhouse of the eighth century consisted of an aggregate

of separate structures, which included a living house (domus),

a bathhouse (balnearius), a bakehouse (pistoria), and a

kitchen house (coquina), plus an entire group of agricultural

service structures, such as the various barns and stables

(scoria, granarium quod parc appellant, etc.). But more

importantly, in paragraphs 6-14 we are furnished with an

item by item account of the component members of the

roof-supporting frame of timber. Their functions are defined

by their names, listed often both in Latin and in their

vernacular Old High German form; and their varying

size and structural importance are reflected in the weight

of the fine that is placed upon their damage or destruction.

Listed in the sequence of their constructional importance

they are:

1. Culmen or first: the "ridge" or "ridge beam" to

which the head of the rafters is fastened. Its demolition

entails the collapse of the entire roof; hence, the largest

fine is set for its destruction (40 shillings). In the Lex

Bajuvariorum the term is alternatingly used in the specific

sense of "ridge" or "ridge pole" or as pars pro toto for the

entire roof of the house.

2. Firstsul: "the post by which the ridge is carried" (eam

columnam a qua culmen sustentatur). The structural importance

of this column finds recognition in the fact that the fine

imposed upon its demolition is set at 12 shillings, almost a

third of the fine imposed for the destruction of the whole

house.

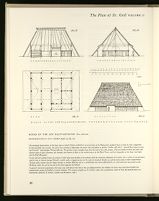

HOUSE OF THE LEX BAJUVARIORUM. 8TH CENTURY

287.B

287.A

287.D

287.C

RECONSTRUCTION BY OTTO GRUBER (1926, 24, fig. 13)

The principal characteristic of the house type on which Gruber modeled his reconstruction of the Bajuvarian standard house is that its roof is supported

by three parallel rows of posts, the center row carrying a ridge beam, the outer rows roof plates or purlins. Gruber calls this a "ground floor house for man

and livestock" (ebenerdiges Wohnstallhaus). The earliest extant examples date from the end of the 15th century. They are found on both the Swiss and

German sides of Lake Constance, the Aargau, the Kanton of Bern in the southern parts of the Black Forest, and less frequently in the Saar river basin

and the Eifel Mountains.

In late and post-medieval times the interior of this house was divided, in accordance with the transverse alignment of its posts, into a series of compartments

used for hay or harvest storage (Schopf), usually under a hipped portion of the roof; for livestock (Stall); as central access area to other compartments

(Tenne) and in winter also for wagon storage; as kitchen (Küch); and as a withdrawal area often subdivided by an axial wall into two private rooms

(Stuben), under the roof at the end of the house opposite the Schopf.

In general structural organization this house may well derive from that of the Lex Bajuvariorum, but whether the latter may have been divided into

compartments cannot be decided on textual evidence. (For extant examples see O. Gruber, 1926, and a posthumous study by him, Bauernhäuser am

Bodensee, edited by K. Gruber, Lindau and Konstanz, 1961.)

3. Winchilsul: this member is explicitly said to stand in

the interior of the building (interioris aedificii). It is part of

a columnar order whose individual posts (assessed at 3

shillings) rate only half of its own value (6 shillings).

The context leaves no doubt that winchilsul was the Old

High German designation for the four corner posts of the

freestanding inner frame of timbers which carried the roof

plates and separated the house internally into a center

space and a peripheral suite of aisles. The corner posts

were obviously of a heavier make than "the remaining

posts of this order" (ceterae huius ordinis), since they were

rated twice their value. But rising only midway up to the

roof, they rate in turn only half the value of the ridge-supporting

firstsul.

4. Columna angularis exterioris ordinis: "the corner

column of the outer order of posts." Its penal value amounts

to 3 shillings, in contradistinction to the "other members

of this order" (aliae columnae huius ordinis) which are

assessed at 1 shilling each.

The relative value assessed to all of these members

suggests that the outer wall posts had only half the strength

of the posts of the inner frame.

5. Trabes: the horizontal long and cross pieces ("tie

beams" and "roof plates"), which frame the principal

uprights together. The relation of paragraph 12 to paragraph

13 leaves no doubt that trabes is used as a generic

designation for all those horizontal timbers which connect

the uprights lengthwise and crosswise. Paragraph 12 deals

with the trabes of the inner order, i.e., the "tie beams"

and "roof plates" which connect the principal inner posts

that separate the nave from the aisles of the hall. Their

penal value (3 shillings) is identical with that of the supports

on which they rest, save for the heavier corner posts

(winchilsul) which rate twice that value. Paragraph 13

deals with the trabes of the outer order (exterioris vero) and

refers to them with the Old High German designation:

6. Spanga, "clamp," so-called "because they hold the

walls together." The fine assessed for the destruction of

these timbers, in modern architectural terminology referred

to as "wall plates," is identical with that of the corresponding

pieces of the inner order (3 shillings).

7. Asseres, laterculi, and axes, the "rafters," the "shingles,"

and the "bracing struts". Their penal value is 1

shilling each.

We are not the first, of course, to try our hand at a

reconstruction of the Bajuvarian standard house based on

this meticulous enumeration of its component structural

members. A first attempt of this kind, consisting of a plan

only, was made in 1902 by Karl Gustav Stephani (fig.

286);[76]

a second, consisting of a plan and various sections

and elevations, in 1926 by Otto Gruber (fig. 287);[77]

and a

third, in the form of an isometric perspective, in 1951 by

Torsten Gebhard (fig. 288).[78]

Stephani's interpretation (fig. 286) of the house as a one-room

structure with a porch on one of its narrow ends

misses the basic message of the text, which makes a clear

distinction between an "inner" and an "outer order of

posts" and within each of these between their "regular

members" and their "corner posts." This suggests a house

that is composed of a center space and a peripheral belt of

outer spaces. Even more untenable is Stephani's explanation

of firstsul as a ridge-supporting center post. I presume

that it was the fact that this term is used in the singular

which induced Stephani to interpret the passage to mean

that the ridge of the Bajuvarian house was supported by a

single post that stood in the very center of the building.

Such an arrangement is constructively incongruous and

must be refuted on both linguistic and architectural

grounds. Linguistically, one finds, the singular form appears

again in the very next paragraph, and there it refers

to a structural member (winchilsul, "corner post") which

by definition cannot have possibly existed in a singular

form, since a house with one corner post would be a logical

absurdity. Constructionally, a ridge beam may be supported

by a center post, but a center post alone could not

possibly hold it in place; its stability required additional

supports at each end of the beam. It must have been

Stephani's faulty exegesis of the text that induced Dehio

to remark with regard to the Lex Bajuvariorum that "the

attempt to reconstruct the Bajuvarian standard house is

unconvincing."[79]

The criticism is fully justified when

applied to Stephani, but it would be wrong if it implied, as

the context suggests, that the source did not lend itself to a

convincing reconstruction.

Gruber's reconstruction (fig. 287) comes considerably

closer to the truth; but his internal subdivision of the house

into areas used as stables, barns, and living quarters are derived

from post-medieval house forms (Old Upper Suebian

farmhouse and Hotzen house) and are, therefore, purely

conjectural. Decidedly wrong in Gruber's reconstruction

is the application of the term winchilsul to all the members

of the "inner order" (designated with the Arabic figure 2

in his plan), because the text distinguishes clearly between

the "corner posts" (winchilsul) and the "other columns

of this order" (ceterae vero huius ordinis).

By far the most convincing of all the existing reconstructions

is that of Thorsten Gebhard (fig. 288). As a point of

minor criticism it might be noted that there is nothing in

the Lex Bajuvariorum which would suggest that the center

space was boarded off against the outer space by the solid

wooden paneling shown in Gebhard's reconstruction;

while, conversely, this reconstruction fails to show a feature

that is explicitly mentioned in the text, namely, the "remaining

posts of the inner order" (ceterae huius ordinis

[columnae]). Gebhard is probably right when he assumes

that the Bajuvarian standard house had its principal

entrance in the middle of one of its long sides, but again

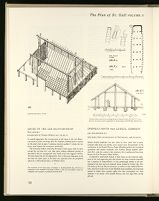

HOUSE OF THE LEX BAJUVARIORUM

288. AXONOMETRIC VIEW

8TH CENTURY

[reconstruction by Thorsten Gebhard, 1951, 234, fig. 3]

In overall appearance this reconstruction of the house of the Lex Bajuvariorum

is fairly convincing. But like Stephani, Gebhard fails to account

for the inner order of posts ("columnae interioris aedificii") which, the text

states, stood between the cornerposts (winchilsul).

The horizontal timbers connecting the heads of these posts could not have

carried the roof load over very wide spans without additional posting as

described in the text; unsupported, they would surely have sagged or broken.

The same holds true for the ridge purlin. Nor is there any indication in the

text that the center space of the house was separated from the peripheral

spaces by a solid wall partition, as Gebhard shows.

The orientation of the large group of buildings at Zwenkau-Harth (fig. 288.X.a) is

conspicuous in the treatment to be found in Quitta, 1958, and was possibly to gain advantageous

solar exposure, or protection from the wind.

ZWENKAU-HARTH NEAR LEIPZIG, GERMANY

288.X.b SECTION

3RD MILLENNIUM B.C.

[after Quitta, Neue Ausgrabungen in Deutchland, 1958, 69 and 75]

Houses divided lengthwise into four aisles by three axial rows of posts,

carrying ridge beam and purlins, were among main characteristics of the

architecture of the Banded Pottery People (Bandkeramiker) who introduced

agriculture and animal husbandry into Central Europe between 50003000

B.C., and who, owing to their sedentary life of seeding and harvesting,

became the first European village builders.

A distinctive construction feature of their houses is the transverse alignment

of the roof-supporting posts that divide the house crosswise internally

into a sequence of compartments—a trait perplexingly similar to the partitioning

of the late and post-medieval houses studied by Gruber (fig. 287).

The house of the Lex Bajuvariorum, as well as its late medieval derivatives,

may have its first roots in this Neolithic house tradition, but the precise

manner in which these concepts might have been transmitted over three

milennia is not known. (For possible Bronze and Iron Age links, see fig.

289.A)

(fig. 289) I have limited myself to showing only those members

which are explicitly mentioned in the Lex. The Lex

does not tell us anything about the position of the hearth,

but the location of the hearth is not in question. In structures

of this type the hearth was always in the middle, or

somewhere else along the axis of the center space, at

maximal distance from the incendiary timbers of the walls

and the roof.

Dehio, then, greatly underrated the importance of the

Lex Bajuvariorum for the history of early medieval house

construction. This code not only lends itself to a structural

reconstruction of the Bajuvarian standard house, but it does

so with singular explicitness, and from the information thus

obtained we can draw general conclusions that are of

importance for the broader issues of our study. Foremost

among these is the recognition that during the eighth

century a European house type existed with a general

design that closely resembled the North Germanic house of

the Saga period. Like the latter, it is a skeletal timber

structure and is covered by a large pitched roof, whose

rafters converge in a ridge pole.

There are some distinctive differences, to be sure. In the

Saga house, as has been pointed out, the ridge pole was carried

by short king posts (dvergr) that rose from the center of

the cross beams. In the house of the Bajuvarians the ridge

was supported by posts that rose from the ground. The

Saga house was three-aisled like the Germanic all-purpose

house discussed below, pp. 45ff. The house of the Lex

Bajuvariorum is four aisled, bearing striking, yet so far

inexplicable, resemblance to a house type common in

Central Europe in the 3rd millenium B.C. (see caption,

288X).

Professor Stefan Riesenfeld in the School of Law, University of

California, Berkeley, has had the kindness to check this translation for

correctness of its legal terminology.

scoria. Other Old High German versions are: scura, sciura, or

schiure; New High German: Scheuer; French: écurie; cf. Heyse, II,

1849, 667.

scof. Other Old High German versions are: scopf, schopf; Middle

High German: shopf and schopfe; New High German: Schopfen, i.e., a

"weather roof"; cf. Grimm, IX, 1899, col. 153.

parc. Other Old High German versions are: pharrich, pherrich;

Middle and New High German: pferch; from Middle Latin parcus, an

enclosure or shed either for animals, or for the storage of grain or

hay; cf. Grimm, VII, 1889, col. 1673.

mita: from Latin meta; Low German: mite; Dutch: mijte; New

High German: Miete; all in the sense of a haystack or stack of sheaves

protected by a conical roof of thatch which rested on poles and could be

lowered and raised according to need; cf. Grimm, VI, 1885, col. 2177.

A typical example of this type of structure can be seen in the background

of the picture of Ruth and Boas in the Dutch Bible of about 1465,

reproduced in fig. 368.

scopar. Other Old High German versions are sopar, sober; New

High German: Schober; a stack of hay, straw, or grain sheaves piled in

the open field; cf. Heyse, II, 1849, 775.

first: identical with New High German First; Middle High German

virst or fuerst; Anglo-Saxon fierst, first; cf. Grimm, III, 1862, cols.

1677-78.

The verb inunwan does not occur in any of the Old High German

dictionaries and glossaries that are available to me, and Eckhardt leaves

it untranslated. However, from the explanatory apposition that follows

(in disperationem vitae fecerit), one would suspect it to be equivalent with

"exposed them to the danger of losing life and limb."

winchil: identical with New High German Winkel, "angle" or

"corner"; cf. Steinmeyer and Sievers, III, 1895, 128, No. 63 (Angulus

winchel, winkil).

trabes: in classical as well as in Medieval Latin this term is used for

the horizontal cross and long beams, which frame the principal uprights

together, i.e., "tie beams," and the "plates."

spanga: identical with New High German Spange, a "clamp," here

used in the specific sense of "wall plate," the horizontal beams that

frame the wall posts together.

asseres. Since we are obviously not dealing here with primary

structural members, asseres cannot be used here in the sense of "post"

or "pole," but is more likely to stand for "board" or "lath," and may

refer to either the covering material of the walls or the grill of laths on

the roof into which the shingles are keyed.

laterculus: in classical Latin "a small brick"; in Medieval Latin,

however, also used for "shingle," as follows from a passage quoted by

Du Cange: "Turris laterculis ligneis cooperta, id est, scandulis" (V, 1938,

35).

axis: in classical Latin "axle tree"; but also "board" or "plank."

Since in its primary sense this term appears to denote a connecting

piece of timber, I should be inclined to assume that it may be used here

for the smaller subsidiary "struts," which stiffen the main frame of the

building, or for the "collar beams," which brace the rafters.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||