The innocents abroad, or, The new Pilgrim's

progress being some account of the steamship Quaker City's pleasure excursion to Europe and the Holy land ; with descriptions of countries, nations, incidents and adventures, as they appeared to the author |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. | CHAPTER XXIII. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. |

| 30. |

| 31. |

| 32. |

| 33. |

| 34. |

| 35. |

| 36. |

| 37. |

| 38. |

| 39. |

| 40. |

| 41. |

| 42. |

| 43. |

| 44. |

| 45. |

| 46. |

| 47. |

| 48. |

| 49. |

| 50. |

| 51. |

| 52. |

| 53. |

| 54. |

| 55. |

| 56. |

| 57. |

| 58. |

| 59. |

| 60. |

| 61. |

| CHAPTER XXIII. The innocents abroad, or, The new Pilgrim's

progress | ||

23. CHAPTER XXIII.

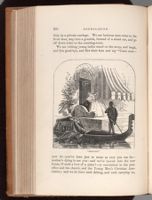

The Venetian gondola is as free and graceful, in its

gliding movement, as a serpent. It is twenty or thirty

feet long, and is narrow and deep, like a canoe; its sharp

bow and stern sweep upward from the water like the horns

of a crescent with the abruptness of the curve slightly modified.

The bow is ornamented with a steel comb with a battle-ax

attachment which threatens to cut passing boats in two occasionally,

but never does. The gondola is painted black because

in the zenith of Venetian magnificence the gondolas became

too gorgeous altogether, and the Senate decreed that all

such display must cease, and a solemn, unembellished black be

substituted. If the truth were known, it would doubtless

appear that rich plebeians grew too prominent in their affectation

of patrician show on the Grand Canal, and required a

wholesome snubbing. Reverence for the hallowed Past and

its traditions keeps the dismal fashion in force now that the

compulsion exists no longer. So let it remain. It is the

color of mourning. Venice mourns. The stern of the boat

is decked over and the gondolier stands there. He uses a

single oar—a long blade, of course, for he stands nearly erect.

A wooden peg, a foot and a half high, with two slight crooks

or curves in one side of it and one in the other, projects above

the starboard gunwale. Against that peg the gondolier takes

a purchase with his oar, changing it at intervals to the other

side of the peg or dropping it into another of the crooks, as

the steering of the craft may demand—and how in the world

around a corner, and make the oar stay in those insignificant

notches, is a problem to me and a never diminishing matter

of interest. I am afraid I study the gondolier's

marvelous skill more than I do the

sculptured palaces we glide among. He

cuts a corner so closely, now and then, or

misses another gondola by such an imperceptible

hair-breadth that I feel myself

“scrooching,” as the children say, just as

one does when a buggy wheel grazes his

elbow. But he makes all his calculations

with the nicest precision, and goes darting

in and out among a Broadway confusion of busy craft with

the easy confidence of the educated hackman. He never

makes a mistake.

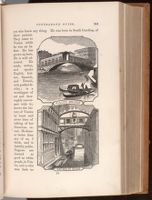

Sometimes we go flying down the great canals at such a gait

that we can get only the merest glimpses into front doors, and

again, in obscure alleys in the suburbs, we put on a solemnity

suited to the silence, the mildew, the stagnant waters, the

clinging weeds, the deserted houses and the general lifelessness

of the place, and move to the spirit of grave meditation.

The gondolier is a picturesque rascal for all he wears no

satin harness, no plumed bonnet, no silken tights. His attitude

is stately; he is lithe and supple; all his movements are

full of grace. When his long canoe, and his fine figure, towering

from its high perch on the stern, are cut against the

evening sky, they make a picture that is very novel and striking

to a foreign eye.

We sit in the cushioned carriage-body of a cabin, with the

curtains drawn, and smoke, or read, or look out upon the passing

boats, the houses, the bridges, the people, and enjoy ourselves

much more than we could in a buggy jolting over our

cobble-stone pavements at home. This is the gentlest, pleasantest

locomotion we have ever known.

But it seems queer—ever so queer—to see a boat doing

front door, step into a gondola, instead of a street car, and go

off down town to the counting-room.

We see visiting young ladies stand on the stoop, and laugh,

and kiss good-bye, and flirt their fans and say “Come soon—

now do—you've been just as mean as ever you can be—

mother's dying to see you—and we've moved into the new

house, O such a love of a place!—so convenient to the post-office

and the church, and the Young Men's Christian Association;

and we do have such fishing, and such carrying on,

come—no distance at all, and if you go down through by St.

Mark's and the Bridge of Sighs, and cut through the alley and

come up by the church of Santa Maria dei Frari, and into the

Grand Canal, there isn't a bit of current—now do come, Sally

Maria—by-bye!” and then the little humbug trips down the

steps, jumps into the gondola, says, under her breath, “Disagreeable

old thing, I hope she won't!” goes skimming away,

round the corner; and the other girl slams the street door and

says, “Well, that infliction's over, any way,—but I suppose

I've got to go and see her—tiresome stuck-up thing!” Human

nature appears to be just the same, all over the world.

We see the diffident young man, mild of moustache, affluent

of hair, indigent of brain, elegant of costume, drive up to her

father's mansion, tell his hackman to bail out and wait, start

fearfully up the steps and meet “the old gentleman” right on

the threshold!—hear him ask what street the new British

Bank is in—as if that were what he came for—and then

bounce into his boat and skurry away with his coward heart

in his boots!—see him come sneaking around the corner

again, directly, with a crack of the curtain open toward the

old gentleman's disappearing gondola, and out scampers his

Susan with a flock of little Italian endearments fluttering

from her lips, and goes to drive with him in the watery

avenues down toward the Rialto.

We see the ladies go out shopping, in the most natural way,

and flit from street to street and from store to store, just in

the good old fashion, except that they leave the gondola, instead

of a private carriage, waiting at the curbstone a couple of

hours for them,—waiting while they make the nice young

clerks pull down tons and tons of silks and velvets and moire

antiques and those things; and then they buy a paper of pins

and go paddling away to confer the rest of their disastrous

patronage on some other firm. And they always have their

purchases sent home just in the good old way. Human nature

is very much the same all over the world; and it is so

like my dear native home to see a Venetian lady go into a

home in a scow. Ah, it is these little touches of nature that

move one to tears in these far-off foreign lands.

We see little girls and boys go out in gondolas with their

nurses, for an airing. We see staid families, with prayer-book

and beads, enter the gondola dressed in their Sunday best, and

float away to church. And at midnight we see the theatre

break up and discharge its swarm of hilarious youth and

beauty; we hear the cries of the hackman-gondoliers, and

behold the struggling crowd jump aboard, and the black

multitude of boats go skimming down the moonlit avenues;

we see them separate here and there, and disappear up divergent

streets; we hear the faint sounds of laughter and of

shouted farewells floating up out of the distance; and then,

the strange pageant being gone, we have lonely stretches of

glittering water—of stately buildings—of blotting shadows—

of weird stone faces creeping into the moonlight—of deserted

bridges—of motionless boats at anchor. And over all broods

that mysterious stillness, that stealthy quiet, that befits so well

this old dreaming Venice.

We have been pretty much every where in our gondola.

We have bought beads and photographs in the stores, and wax

matches in the Great Square of St. Mark. The last remark

suggests a digression. Every body goes to this vast square in

the evening. The military bands play in the centre of it and

countless couples of ladies and gentlemen promenade up and

down on either side, and platoons of them are constantly

drifting away toward the old Cathedral, and by the venerable

column with the Winged Lion of St. Mark on its top, and out

to where the boats lie moored; and other platoons are as constantly

arriving from the gondolas and joining the great

throng. Between the promenaders and the side-walks are

seated hundreds and hundreds of people at small tables,

smoking and taking granita, (a first cousin to ice-cream;) on

the side-walks are more employing themselves in the same

way. The shops in the first floor of the tall rows of buildings

that wall in three sides of the square are brilliantly lighted,

the scene is as bright and spirited and full of cheerfulness as

any man could desire. We enjoy it thoroughly. Very many

of the young women are exceedingly pretty and dress with

rare good taste. We are gradually and laboriously learning

the ill-manners of staring them unflinchingly in the face—not

because such conduct is agreeable to us, but because it is the

custom of the country and they say the girls like it. We wish

to learn all the curious, outlandish ways of all the different

countries, so that we can “show off” and astonish people

when we get home. We wish to excite the envy of our untraveled

friends with our strange foreign fashions which we

can't shake off. All our passengers are paying strict attention

to this thing, with the end in view which I have

mentioned. The gentle reader will never, never know

what a consummate ass he can become, until he goes abroad.

I speak now, of course, in the supposition that the gentle

reader has not been abroad, and therefore is not already a consummate

ass. If the case be otherwise, I beg his pardon and

extend to him the cordial hand of fellowship and call him

brother. I shall always delight to meet an ass after my own

heart when I shall have finished my travels.

On this subject let me remark that there are Americans

abroad in Italy who have actually forgotten their mother

tongue in three months—forgot it in France. They can not

even write their address in English in a hotel register. I append

these evidences, which I copied verbatim from the register

of a hotel in a certain Italian city:

“Wm. L. Ainsworth, travailleur (he meant traveler, I suppose,) Etats Unis.

“George P. Morton et fils, d'Amerique.

“Lloyd B. Williams, et trois amis, ville de Boston, Amerique.

“J. Ellsworth Baker, tout de suite de France, place de naissance Amerique, destination la Grand Bretagne.”

I love this sort of people. A lady passenger of ours tells

of a fellow-citizen of hers who spent eight weeks in Paris and

then returned home and addressed his dearest old bosom

and said, “'Pon my soul it is aggravating, but I cahn't help it

—I have got so used to speaking nothing but French, my dear

Erbare—damme there it goes again!—got so used to French

pronunciation that I cahn't get rid of it—it is positively annoying,

I assure you.” This entertaining idiot, whose name

was Gordon, allowed himself to be hailed three times in the

street before he paid any attention, and then begged a thousand

pardons and said he had grown so accustomed to hearing

himself addressed as M'sieu Gor-r-dong,” with a roll to the r,

that he had forgotten the legitimate

sound of his name! He wore a rose

in his button-hole; he gave the French

salutation—two flips of the hand in

front of the face; he called Paris Pairree

in ordinary English conversation;

he carried envelopes bearing foreign

postmarks protruding from his breast-pocket;

he cultivated a moustache and

imperial, and did what else he could to

suggest to the beholder his pet fancy

that he resembled Louis Napoleon—

and in a spirit of thankfulness which is

entirely unaccountable, considering the

slim foundation there was for it, he

praised his Maker that he was as he

was, and went on enjoying his little

life just the same as if he really had

been deliberately designed and erected by the great Architect

of the Universe.

Think of our Whitcombs, and our Ainsworths and our

Williamses writing themselves down in dilapidated French

in foreign hotel registers! We laugh at Englishmen, when

we are at home, for sticking so sturdily to their national ways

and customs, but we look back upon it from abroad very forgivingly.

It is not pleasant to see an American thrusting his

nationality forward obtrusively in a foreign land, but Oh, it is

male nor female, neither fish, flesh, nor fowl—a poor, miserable,

hermaphrodite Frenchman!

Among a long list of churches, art galleries, and such

things, visited by us in Venice, I shall mention only one—the

church of Santa Maria dei Frari. It is about five hundred

years old, I believe, and stands on twelve hundred thousand

piles. In it lie the body of Canova and the heart of Titian,

under magnificent monuments. Titian died at the age of

almost one hundred years. A plague which swept away fifty

thousand lives was raging at the time, and there is notable

evidence of the reverence in which the great painter was

held, in the fact that to him alone the state permitted a public

funeral in all that season of terror and death.

In this church, also, is a monument to the doge Foscari,

whose name a once resident of Venice, Lord Byron, has made

permanently famous.

The monument to the doge Giovanni Pesaro, in this church,

is a curiosity in the way of mortuary adornment. It is eighty

feet high and is fronted like some fantastic pagan temple.

Against it stand four colossal Nubians, as black as night,

dressed in white marble garments. The black legs are bare,

and through rents in sleeves and breeches, the skin, of

shiny black marble, shows. The artist was as ingenious as

his funeral designs were absurd. There are two bronze skeletons

bearing scrolls, and two great dragons uphold the sarcophagus.

On high, amid all this grotesqueness, sits the departed

doge.

In the conventual buildings attached to this church are the

state archives of Venice. We did not see them, but they

are said to number millions of documents. “They are the

records of centuries of the most watchful, observant and suspicious

government that ever existed—in which every thing

was written down and nothing spoken out.” They fill nearly

three hundred rooms. Among them are manuscripts from the

archives of nearly two thousand families, monasteries and

convents. The secret history of Venice for a thousand years

of hireling spies and masked bravoes—food, ready to

hand, for a world of dark and mysterious romances.

Yes, I think we have seen all of Venice. We have seen, in

these old churches, a profusion of costly and elaborate

sepulchre ornamentation such

as we never dreampt of before.

We have stood in the dim religious

light of these hoary

sanctuaries, in the midst of

long ranks of dusty monuments

and effigies of the great

dead of Venice, until we

seemed drifting back, back,

back, into the solemn past,

and looking upon the scenes

and mingling with the peoples

of a remote antiquity. We

have been in a half-waking

sort of dream all the time. I

do not know how else to describe

the feeling. A part of

our being has remained still

in the nineteenth century,

while another part of it has

seemed in some unaccountable

way walking among the phantoms

of the tenth.

We have seen famous pictures until our eyes are weary with

looking at them and refuse to find interest in them any longer.

And what wonder, when there are twelve hundred pictures by

Palma the Younger in Venice and fifteen hundred by Tintoretto?

And behold there are Titians and the works of other

artists in proportion. We have seen Titian's celebrated Cain

and Abel, his David and Goliah, his Abraham's Sacrifice.

We have seen Tintoretto's monster picture, which is seventy-four

feet long and I do not know how many feet high, and

of martyrs enough, and saints enough, to regenerate the

world. I ought not to confess it, but still, since one has no

opportunity in America to acquire a critical judgment in art,

and since I could not hope to become educated in it in Europe

in a few short weeks, I may therefore as well acknowledge

with such apologies as may be due, that to me it seemed that

when I had seen one of these martyrs I had seen them all.

They all have a marked family resemblance to each other, they

dress alike, in coarse monkish robes and sandals, they are all

bald headed, they all stand in about the same attitude, and

without exception they are gazing heavenward with countenances

which the Ainsworths, the Mortons and the Williamses,

et fils, inform me are full of “expression.” To me there

is nothing tangible about these imaginary portraits, nothing

that I can grasp and take a living interest in. If great Titian

had only been gifted with prophecy, and had skipped a martyr,

and gone over to England and painted a portrait of Shakspeare,

even as a youth, which we could all have confidence in

now, the world down to the latest generations would have forgiven

him the lost martyr in the rescued seer. I think posterity

could have spared one more martyr for the sake of a

great historical picture of Titian's time and painted by his

brush—such as Columbus returning in chains from the discovery

of a world, for instance. The old masters did paint

some Venetian historical pictures, and these we did not tire of

looking at, notwithstanding representations of the formal introduction

of defunct doges to the Virgin Mary in regions beyond

the clouds clashed rather harshly with the proprieties, it

seemed to us.

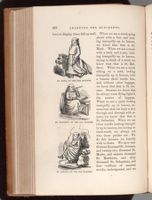

But humble as we are, and unpretending, in the matter of

art, our researches among the painted monks and martyrs

have not been wholly in vain. We have striven hard to learn.

We have had some success. We have mastered some things,

possibly of trifling import in the eyes of the learned, but to

us they give pleasure, and we take as much pride in our little

acquirements as do others who have learned far more, and we

about with a lion and looking

tranquilly up to heaven,

we know that that is St.

Mark. When we see a monk

with a book and a pen, looking

tranquilly up to heaven,

trying to think of a word, we

know that that is St. Matthew.

When we see a monk

sitting on a rock, looking

tranquilly up to heaven, with

a human skull beside him,

and without other baggage,

we know that that is St. Jerome.

Because we know that

he always went flying light in

the matter of baggage.

When we see a party looking

tranquilly up to heaven, unconscious

that his body is shot

through and through with arrows,

we know that that is

St. Sebastian. When we see

other monks looking tranquilly

up to heaven, but having no

trade-mark, we always ask

who those parties are. We

do this because we humbly

wish to learn. We have seen

thirteen thousand St. Jeromes,

and twenty-two thousand St.

Marks, and sixteen thousand

St. Matthews, and sixty

thousand St. Sebastians, and

four millions of assorted

monks, undesignated, and we

of these various pictures, and had a larger experience, we

shall begin to take an absorbing

interest in them like our cultivated

countrymen from

Amerique.

Now it does give me real pain

to speak in this almost unappreciative

way of the old masters

and their martyrs, because good

friends of mine in the ship—

friends who do thoroughly and

conscientiously appreciate them

and are in every way competent

to discriminate between good

pictures and inferior ones—have

urged me for my own sake not

to make public the fact that I

lack this appreciation and this

critical discrimination myself.

I believe that what I have written

and may still write about

pictures will give them pain, and

I am honestly sorry for it. I

even promised that I would

hide my uncouth sentiments in

my own breast. But alas! I

never could keep a promise. I

do not blame myself for this

weakness, because the fault

must lie in my physical organization. It is likely that such a

very liberal amount of space was given to the organ which

enables me to make promises, that the organ which should

enable me to keep them was crowded out. But I grieve not.

I like no half-way things. I had rather have one faculty

nobly developed than two faculties of mere ordinary capacity.

I certainly meant to keep that promise, but I find I can not do

of pictures, and can I see them through others' eyes?

If I did not so delight in the grand pictures that are spread

before me every day of my life by that monarch of all the

old masters, Nature, I should come to believe, sometimes, that

I had in me no appreciation of the beautiful, whatsoever.

It seems to me that whenever I glory to think that for once

I have discovered an ancient painting that is beautiful and

worthy of all praise, the pleasure it gives me is an infallible

proof that it is not a beautiful picture and not in any wise

worthy of commendation. This very thing has occurred

more times than I can mention, in Venice. In every single

instance the guide has crushed out my swelling enthusiam

with the remark:

“It is nothing—it is of the Renaissance.”

I did not know what in the mischief the Renaissance was,

and so always I had to simply say,

“Ah! so it is—I had not observed it before.”

I could not bear to be ignorant before a cultivated negro,

the offspring of a South Carolina slave. But it occurred too

often for even my self-complacency, did that exasperating “It

is nothing—it is of the Renaissance.” I said at last:

“Who is this Renaissance? Where did he come from?

Who gave him permission to cram the Republic with his

execrable daubs?”

We learned, then, that Renaissance was not a man; that

renaissance was a term used to signify what was at best but an

imperfect rejuvenation of art. The guide said that after

Titian's time and the time of the other great names we had

grown so familiar with, high art declined; then it partially

rose again—an inferior sort of painters sprang up, and these

shabby pictures were the work of their hands. Then I said,

in my heat, that I “wished to goodness high art had declined

five hundred years sooner.” The Renaissance pictures suit me

very well, though sooth to say its school were too much given

to painting real men and did not indulge enough in martyrs.

The guide I have spoken of is the only one we have had

slave parents.

They came to

Venice while

he was an infant.

He has

grown up here.

He is well educated.

He

reads, writes,

and speaks

English, Italian,

Spanish,

and French,

with perfect facility;

is a

worshipper of

art and thoroughly

conversant

with it;

knows the history

of Venice

by heart and

never tires of

talking of her

illustrious career.

He dresses

better than

any of us, I

think, and is

daintily polite.

Negroes are

deemed as

good as white

people, in Venice,

and so this

man feels no

I have had another shave. I was writing in our front room

this afternoon and trying hard to keep my attention on my

work and refrain from looking out upon the canal. I was

resisting the soft influences of the climate as well as I could,

and endeavoring to overcome the desire to be indolent and

happy. The boys sent for a barber. They asked me if I

would be shaved. I reminded them of my tortures in Genoa,

Milan, Como; of my declaration that I would suffer no more

on Italian soil. I said “Not any for me, if you please.”

I wrote on. The barber began on the doctor. I heard him

say:

“Dan, this is the easiest shave I have had since we left the

ship.”

He said again, presently:

“Why Dan, a man could go to sleep with this man shaving

him.”

Dan took the chair. Then he said:

“Why this is Titian. This is one of the old masters.”

I wrote on. Directly Dan said:

“Doctor, it is perfect luxury. The ship's barber isn't any

thing to him.”

My rough beard was distressing me beyond measure. The

barber was rolling up his apparatus. The temptation was too

strong. I said:

“Hold on, please. Shave me also.”

I sat down in the chair and closed my eyes. The barber

soaped my face, and then took his razor and gave me a rake

that well nigh threw me into convulsions. I jumped out of

the chair: Dan and the doctor were both wiping blood off

their faces and laughing.

I said it was a mean, disgraceful fraud.

They said that the misery of this shave had gone so far beyond

any thing they had ever experienced before, that they could not

bear the idea of losing such a chance of hearing a cordial

opinion from me on the subject.

It was shameful. But there was no help for it. The skinning

was begun and had to be finished. The tears flowed

with every rake, and so did the fervent execrations. The

barber grew confused, and brought blood every time. I think

the boys enjoyed it better than any thing they have seen or

heard since they left home.

We have seen the Campanile, and Byron's house and Balbi's

the geographer, and the palaces of all ancient dukes

and doges of Venice, and we have seen their effeminate descendants

airing their nobility in fashionable French attire

in the Grand Square of St. Mark, and eating ices and drinking

cheap wines, instead of wearing gallant coats of mail and

destroying fleets and armies as their great ancestors did in the

days of Venetian glory. We have seen no bravoes with poisoned

stilettos, no masks, no wild carnival; but we have seen

the ancient pride of Venice, the grim Bronze Horses that

figure in a thousand legends. Venice may well cherish them,

for they are the only horses she ever had. It is said there are

hundreds of people in this curious city who never have seen a

living horse in their lives. It is entirely true, no doubt.

And so, having satisfied ourselves, we depart to-morrow,

and leave the venerable Queen of the Republics to summon

her vanished ships, and marshal her shadowy armies, and

know again in dreams the pride of her old renown.

| CHAPTER XXIII. The innocents abroad, or, The new Pilgrim's

progress | ||