The innocents abroad, or, The new Pilgrim's

progress being some account of the steamship Quaker City's pleasure excursion to Europe and the Holy land ; with descriptions of countries, nations, incidents and adventures, as they appeared to the author |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. |

| 11. |

| 12. |

| 13. |

| 14. |

| 15. |

| 16. |

| 17. |

| 18. |

| 19. |

| 20. |

| 21. |

| 22. |

| 23. |

| 24. |

| 25. |

| 26. |

| 27. |

| 28. |

| 29. |

| 30. |

| 31. |

| 32. | CHAPTER XXXII. |

| 33. |

| 34. |

| 35. |

| 36. |

| 37. |

| 38. |

| 39. |

| 40. |

| 41. |

| 42. |

| 43. |

| 44. |

| 45. |

| 46. |

| 47. |

| 48. |

| 49. |

| 50. |

| 51. |

| 52. |

| 53. |

| 54. |

| 55. |

| 56. |

| 57. |

| 58. |

| 59. |

| 60. |

| 61. |

| CHAPTER XXXII. The innocents abroad, or, The new Pilgrim's

progress | ||

32. CHAPTER XXXII.

HOME, again! For the first time, in many weeks, the

ship's entire family met and shook hands on the

quarter-deck. They had gathered from many points of the

compass and from many lands, but not one was missing; there

was no tale of sickness or death among the flock to dampen

the pleasure of the reunion. Once more there was a full

audience on deck to listen to the sailors' chorus as they got the

anchor up, and to wave an adieu to the land as we sped away

from Naples. The seats were full at dinner again, the domino

parties were complete, and the life and bustle on the upper

deck in the fine moonlight at night was like old times—old

times that had been gone weeks only, but yet they were weeks

so crowded with incident, adventure and excitement, that they

seemed almost like years. There was no lack of cheerfulness

on board the Quaker City. For once, her title was a misnomer.

At seven in the evening, with the western horizon all golden

from the sunken sun, and specked with distant ships, the full

moon sailing high over head, the dark blue of the sea under

foot, and a strange sort of twilight affected by all these different

lights and colors around us and about us, we sighted

superb Stromboli. With what majesty the monarch held his

lonely state above the level sea! Distance clothed him in a

purple gloom, and added a veil of shimmering mist that so

softened his rugged features that we seemed to see him through

a web of silver gauze. His torch was out; his fires were

smoldering; a tall column of smoke that rose up and lost

he was a living Autocrat of the Sea and not the spectre of a

dead one.

At two in the morning we swept through the Straits of

Messina, and so bright was the moonlight that Italy on the

one hand and Sicily on the other seemed almost as distinctly

visible as though we looked at them from the middle of a

street we were traversing. The city of Messina, milk-white,

and starred and spangled all over with gaslights, was a fairy

spectacle. A great party of us were on deck smoking and

making a noise, and waiting to see famous Scylla and Charybdis.

And presently the Oracle stepped out with his eternal

spy-glass and squared himself on the deck like another Colossus

of Rhodes. It was a surprise to see him abroad at such an

hour. Nobody supposed he cared anything about an old fable

like that of Scylla and Charybdis. One of the boys said:

“Hello, doctor, what are you doing up here at this time of

night?—What do you want to see this place for?”

“What do I want to see this place for? Young man, little

do you know me, or you wouldn't ask such a question. I wish

to see all the places that's mentioned in the Bible.”

“Stuff—this place isn't mentioned in the Bible.”

“It ain't mentioned in the Bible!—this place ain't—well

now, what place is this, since you know so much about it?”

“Why it's Scylla and Charybdis.”

“Scylla and Cha—confound it, I thought it was Sodom and

Gomorrah!”

And he closed up his glass and went below. The above is

the ship story. Its plausibility is marred a little by the fact

that the Oracle was not a biblical student, and did not spend

much of his time instructing himself about Scriptural localities.

—They say the Oracle complains, in this hot weather, lately,

that the only beverage in the ship that is passable, is the

butter. He did not mean butter, of course, but inasmuch as

that article remains in a melted state now since we are out of

ice, it is fair to give him the credit of getting one long word in

the right place, anyhow, for once in his life. He said, in

Rome, that the Pope was a noble-looking old man, but he

never did think much of his Iliad.

We spent one pleasant day skirting along the Isles of

Greece. They are very mountainous. Their prevailing tints

are gray and brown, approaching to red. Little white villages

surrounded by trees, nestle in the valleys or roost upon the

lofty perpendicular sea-walls.

We had one fine sunset—a rich carmine flush that suffused

the western sky and cast a ruddy glow far over the sea.—Fine

sunsets seem to be rare in this part of the world—or at least,

striking ones. They are soft, sensuous, lovely—they are exquisite,

refined, effeminate, but we have seen no sunsets here

yet like the gorgeous conflagrations that flame in the track of

the sinking sun in our high northern latitudes.

But what were sunsets to us, with the wild excitement upon

us of approaching the most renowned of cities! What cared

thousand other heroes of the great Past were marching in

ghostly procession through our fancies? What were sunsets

to us, who were about to live and breathe and walk in actual

Athens; yea, and go far down into the dead centuries and bid

in person for the slaves, Diogenes and Plato, in the public

market-place, or gossip with the neighbors about the siege of

Troy or the splendid deeds of Marathon? We scorned to consider

sunsets.

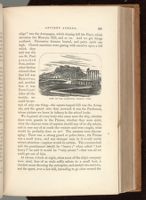

We arrived, and entered the ancient harbor of the Piræus at

last. We dropped anchor within half a mile of the village.

Away off, across the undulating Plain of Attica, could be seen

a little square-topped hill with a something on it, which our

glasses soon discovered to be the ruined edifices of the citadel

of the Athenians, and most prominent among them loomed the

venerable Parthenon. So exquisitely clear and pure is this

wonderful atmosphere that every column of the noble structure

was discernible through the telescope, and even the smaller

ruins about it assumed some semblance of shape. This at a

distance of five or six miles. In the valley, near the Acropolis,

(the square-topped hill before spoken of,) Athens itself could

be vaguely made out with an ordinary lorgnette. Every body

was anxious to get ashore and visit these classic localities as

quickly as possible. No land we had yet seen had aroused

such universal interest among the passengers.

But bad news came. The commandant of the Piræus came

in his boat, and said we must either depart or else get outside

the harbor and remain imprisoned in our ship, under rigid

quarantine, for eleven days! So we took up the anchor and

moved outside, to lie a dozen hours or so, taking in supplies,

and then sail for Constantinople. It was the bitterest disappointment

we had yet experienced. To lie a whole day in

sight of the Acropolis, and yet be obliged to go away without

visiting Athens! Disappointment was hardly a strong enough

word to describe the circumstances.

All hands were on deck, all the afternoon, with books and

maps and glasses, trying to determine which “narrow rocky

elevation the Museum Hill, and so on. And we got things

confused. Discussion became heated, and party spirit ran

high. Church members were gazing with emotion upon a hill

which they

said was the

one St. Paul

preached

from, and another

faction

claimed that

that hill was

Hymettus,

and another

that it was

Pentelicon!

After all the

trouble, we

could be certain

of only one thing—the square-topped hill was the Acropolis,

and the grand ruin that crowned it was the Parthenon,

whose picture we knew in infancy in the school books.

We inquired of every body who came near the ship, whether

there were guards in the Piræus, whether they were strict,

what the chances were of capture should any of us slip ashore,

and in case any of us made the venture and were caught, what

would be probably done to us? The answers were discouraing:

There was strong guard or police force; the Piræus

was a small town, and any stranger seen in it would surely

attract attention—capture would be certain. The commandant

said the punishment would be “heavy;” when asked “how

heavy?” he said it would be “very severe”—that was all we

could get out of him.

At eleven o'clock at night, when most of the ship's company

were abed, four of us stole softly ashore in a small boat, a

clouded moon favoring the enterprise, and started two and two,

and far apart, over a low hill, intending to go clear around the

stealthily over that rocky, nettle-grown eminence, made me

feel a good deal as if I were on my way somewhere to steal

something. My immediate comrade and I talked in an undertone

about quarantine laws and their penalties, but we found

nothing cheering in the subject. I was posted. Only a few

days before, I was talking with our captain, and he mentioned

the case of a man who swam ashore from a quarantined ship

somewhere, and got imprisoned six months for it; and when

he was in Genoa a few years ago, a captain of a quarantined

ship went in his boat to a departing ship, which was already

outside of the harbor, and put a letter on board to be taken to

his family, and the authorities imprisoned him three months

for it, and then conducted him and his ship fairly to sea, and

warned him never to show himself in that port again while he

lived. This kind of conversation did no good, further than to

give a sort of dismal interest to our quarantine-breaking expedition,

and so we dropped it. We made the entire circuit of

the town without seeing any body but one man, who stared at

us curiously, but said nothing, and a dozen persons asleep on

the ground before their doors, whom we walked among and

never woke—but we woke up dogs enough, in all conscience—

we always had one or two barking at our heels, and several

times we had as many as ten and twelve at once. They made

such a preposterous din that persons aboard our ship said they

could tell how we were progressing for a long time, and where

we were, by the barking of the dogs. The clouded moon still

favored us. When we had made the whole circuit, and were

passing among the houses on the further side of the town, the

moon came out splendidly, but we no longer feared the light.

As we approached a well, near a house, to get a drink, the

owner merely glanced at us and went within. He left the

quiet, slumbering town at our mercy. I record it here proudly,

that we didn't do any thing to it.

Seeing no road, we took a tall hill to the left of the distant

Acropolis for a mark, and steered straight for it over all obstructions,

and over a little rougher piece of country than

Part of the way it was covered with small, loose stones—we

trod on six at a time, and they all rolled. Another part of it

was dry, loose, newly-ploughed ground. Still another part of

it was a long stretch of low grape-vines, which were tanglesome

and troublesome, and which we took to be brambles.

The Attic Plain, barring the grape-vines, was a barren, desolate,

unpoetical waste—I wonder what it was in Greece's Age

of Glory, five hundred years before Christ?

In the neighborhood of one o'clock in the morning, when

we were heated with fast walking and parched with thirst,

Denny exclaimed, “Why, these weeds are grape-vines!” and

in five minutes we had a score of bunches of large, white, delicious

grapes, and were reaching down for more when a dark

shape rose mysteriously up out of the shadows beside us and

said “Ho!” And so we left.

In ten minutes more we struck into a beautiful road, and

unlike some

others we

had stumbled

upon at

intervals, it

led in the

right direction.

We

followed it.

It was broad,

and smooth,

and white—

handsome

and in perfect

repair,

and shaded

on both sides

for a mile or

so with single

ranks of

trees, and also with luxuriant vineyards. Twice we entered

from some invisible place. Whereupon we left again. We

speculated in grapes no more on that side of Athens.

Shortly we came upon an ancient stone aqueduct, built upon

arches, and from that time forth we had ruins all about us—

we were approaching our journey's end. We could not see

the Acropolis now or the high hill, either, and I wanted to

follow the road till we were abreast of them, but the others

overruled me, and we toiled laboriously up the stony hill immediately

in our front—and from its summit saw another—

climbed it and saw another! It was an hour of exhausting

work. Soon we came upon a row of open graves, cut in the

solid rock—(for a while

one of them served Socrates

for a prison)—we

passed around the shoulder

of the hill, and the

citadel, in all its ruined

magnificence, burst upon

us! We hurried across

the ravine and up a

winding road, and stood

on the old Acropolis, with

the prodigious walls of

the citadel towering

above our heads. We

did not stop to inspect

their massive blocks of

marble, or measure their

height, or guess at their

extraordinary thickness,

but passed at once

through a great arched

passage like a railway

tunnel, and went straight to the gate that leads to the ancient

temples. It was locked! So, after all, it seemed that we were

not to see the great Parthenon face to face. We sat down and

structure of wood—we would break it down. It seemed like

desecration, but then we had traveled far, and our necessities

were urgent. We could not hunt up guides and keepers—we

must be on the ship before daylight. So we argued. This

was all very fine, but when we came to break the gate, we

could not do it. We moved around an angle of the wall and

found a low bastion—eight feet high without—ten or twelve

within. Denny prepared to scale it, and we got ready to follow.

By dint of hard scrambling he finally straddled the top,

but some loose stones crumbled away and fell with a crash

into the court within. There was instantly a banging of doors

and a shout. Denny dropped from the wall in a twinkling,

and we retreated in disorder to the gate. Xerxes took that

mighty citadel four hundred and eighty years before Christ,

when his five millions of soldiers and camp-followers followed

him to Greece, and if we four Americans could have remained

unmolested five minutes longer, we would have taken it too.

The garrison had turned out—four Greeks. We clamored

at the gate, and they admitted us. [Bribery and corruption.]

We crossed a large court, entered a great door, and stood

upon a pavement of purest white marble, deeply worn by fool-prints.

Before us, in the flooding moonlight, rose the noblest

ruins we had ever looked upon—the Propylæ; a small Temple

of Minerva; the Temple of Hercules, and the grand Parthenon.

[We got these names from the Greek guide, who

didn't seem to know more than seven men ought to know.]

These edifices were all built of the whitest Pentelic marble,

but have a pinkish stain upon them now. Where any part is

broken, however, the fracture looks like fine loaf sugar. Six

caryatides, or marble women, clad in flowing robes, support

the portico of the Temple of Hercules, but the porticos and

colonnades of the other structures are formed of massive Doric

and Ionic pillars, whose flutings and capitals are still measurably

perfect, notwithstanding the centuries that have gone

over them and the sieges they have suffered. The Parthenon,

originally, was two hundred and twenty-six feet long, one hundred

eight in each, at either end, and single rows of seventeen

each down the sides, and was one of the most graceful and

beautiful edifices ever erected.

Most of the Parthenon's imposing columns are still standing,

but the roof is gone. It was a perfect building two hundred

and fifty years ago, when a shell dropped into the Venetian

magazine stored here, and the explosion which followed

wrecked and unroofed it. I remember but little about the

Parthenon, and I have put in one or two facts and figures for

the use of other people with short memories. Got them from

the guide-book.

As we wandered thoughtfully down the marble-paved length

of this stately temple, the scene about us was strangely impressive.

Here and there, in lavish profusion, were gleaming

white statues of men and women, propped against blocks of

all looking mournful in the moonlight, and startlingly

human! They rose up and confronted the midnight

intruder on every side—they stared at him with stony eyes

from unlooked-for nooks and recesces; they peered at him

over fragmentary heaps far down the desolate corridors; they

barred his way in the midst of the broad forum, and solemnly

pointed with handless arms the way from the sacred fane; and

through the roofless temple the moon looked down, and banded

the floor and darkened the scattered fragments and broken

statues with the slanting shadows of the columns.

What a world of ruined sculpture was about us! Set up in

rows—stacked up in piles—scattered broadcast over the wide

area of the Acropolis—were hundreds of crippled statues of all

sizes and of the most exquisite workmanship; and vast fragments

of marble that once belonged to the entablatures, covered

with bas-reliefs representing battles and sieges, ships of

war with three and four tiers of oars, pageants and processions

—every thing one could think of. History says that the temples

of the Acropolis were filled with the noblest works of

Praxiteles and Phidias, and of many a great master in sculpture

besides—and surely these elegant fragments attest it.

We walked out into the grass-grown, fragment-strewn court

beyond the Parthenon. It startled us, every now and then, to

see a stony white face stare suddenly up at us out of the grass

with its dead eyes. The place seemed alive with ghosts. I

half expected to see the Athenian heroes of twenty centuries

ago glide out of the shadows and steal into the old temple

they knew so well and regarded with such boundless pride.

The full moon was riding high in the cloudless heavens,

now. We sauntered carelessly and unthinkingly to the edge

of the lofty battlements of the citadel, and looked down—a

vision! And such a vision! Athens by moonlight! The

prophet that thought the splendors of the New Jerusalem

were revealed to him, surely saw this instead! It lay in the

level plain right under our feet—all spread abroad like a picture—and

we looked down upon it as we might have looked

house, every window, every clinging vine, every projection,

was as distinct and sharply marked as if the time were noonday;

and yet there was no glare, no glitter, nothing harsh or

repulsive—the noiseless city was flooded with the mellowest

light that ever streamed from the moon, and seemed like some

living creature wrapped in peaceful slumber. On its further

side was a little temple, whose delicate pillars and ornate front

glowed with a rich lustre that chained the eye like a spell; and

nearer by, the palace of the king reared its creamy walls out

of the midst of a great garden of shrubbery that was flecked

all over with a random shower of amber lights—a spray of

golden sparks that lost their brightness in the glory of the

moon, and glinted softly upon the sea of dark foliage like the

pallid stars of the milky-way. Overhead the stately columns,

majestic still in their ruin—under foot the dreaming city—in

the distance the silver sea—not on the broad earth is there another

picture half so beautiful!

As we turned and moved again through the temple, I wished

that the illustrious men who had sat in it in the remote ages

could visit it again and reveal themselves to our curious eyes

—Plato, Aristotle, Demosthenes, Socrates, Phocion, Pythagoras,

Euclid, Pindar, Xenophon, Herodotus, Praxiteles and

Phidias, Zeuxis the painter. What a constellation of celebrated

names! But more than all, I wished that old Diogenes,

groping so patiently with his lantern, searching so zealously

for one solitary honest man in all the world, might meander

along and stumble on our party. I ought not to say it, may

be, but still I suppose he would have put out his light.

We left the Parthenon to keep its watch over old Athens, as

it had kept it for twenty-three hundred years, and went and

stood outside the walls of the citadel. In the distance was the

ancient, but still almost perfect Temple of Theseus, and close

by, looking to the west, was the Bema, from whence Demosthenes

thundered his philippies and fired the wavering patriotism

of his countrymen. To the right was Mars Hill, where

the Areopagus sat in ancient times, and where St. Paul defined

daily” with the gossip-loving Athenians. We climbed

the stone steps St. Paul ascended, and stood in the square-cut

place he stood in, and tried to recollect the Bible account of

the matter—but for certain reasons, I could not recall the

words. I have found them since:

“Now while Paul waited for them at Athens, his spirit was stirred in him,

when he saw the city wholly given up to idolatry.

“Therefore disputed he in the synagogue with the Jews, and with the devout

persons, and in the market daily with them that met with him.

“And they took him and brought him unto Areopagus, saying, May we know

what this new doctrine whereof thou speakest is?

“Then Paul stood in the midst of Mars hill, and said, Ye men of Athens, I perceive

that in all things ye are too superstitious;

“For as I passed by and beheld your devotions, I found an altar with this inscription:

To the Unknown God. Whom, therefore, ye ignorantly worship, him

declare I unto you.”—Acts, ch. xvii.”

It occurred to us, after a while, that if we wanted to get

home before daylight betrayed us, we had better be moving.

So we hurried away. When far on our road, we had a parting

view of the Parthenon, with the moonlight streaming through

its open colonnades and touching its capitals with silver. As

it looked then, solemn, grand, and beautiful it will always

remain in our memories.

As we marched along, we began to get over our fears, and

ceased to care much about quarantine scouts or any body else.

We grew bold and reckless; and once, in a sudden burst of

courage, I even threw a stone at a dog. It was a pleasant

reflection, though, that I did not hit him, because his master

might just possibly have been a policeman. Inspired by this

happy failure, my valor became utterly uncontrollable, and at

intervals I absolutely whistled, though on a moderate key.

But boldness breeds boldness, and shortly I plunged into a

vineyard, in the full light of the moon, and captured a gallon

of superb grapes, not even minding the presence of a peasant

who rode by on a mule. Denny and Birch followed my example.

Jackson was all swollen up with courage, too, and he was

obliged to enter a vineyard presently. The first bunch he

seized brought trouble. A

frowsy, bearded brigand

sprang into the road with

a shout, and flourished a

musket in the light of the

moon! We sidled toward

the Piræus—not running,

you understand, but only

advancing with celerity. The brigand shouted again, but still

we advanced. It was getting late, and we had no time to fool

away on every ass that wanted to drivel Greek platitudes to us.

We would just as soon have talked with him as not if we had

not been in a hurry. Presently Denny said, “Those fellows

are following us!”

We turned, and, sure enough, there they were—three fantastic

pirates armed with guns. We slackened our pace to let

them come up, and in the meantime I got out my cargo of

grapes and dropped them firmly but reluctantly into the shadows

by the wayside. But I was not afraid. I only felt that

it was not right to steal grapes. And all the more so when the

owner was around—and not only around, but with his friends

around also. The villains came up and searched a bundle Dr.

it had nothing in it but some holy rocks from Mars Hill, and

these were not contraband. They evidently suspected him of

playing some wretched fraud upon them, and seemed half inclined

to scalp the party. But finally they dismissed us with

a warning, couched in excellent Greek, I suppose, and dropped

tranquilly in our wake. When they had gone three hundred

yards they stopped, and we went on rejoiced. But behold,

another armed rascal came out of the shadows and took their

place, and followed us two hundred yards. Then he delivered

us over to another miscreant, who emerged from some mysterious

place, and he in turn to another! For a mile and a half

our rear was guarded all the while by armed men. I never

traveled in so much state before in all my life.

It was a good while after that before we ventured to steal

any more grapes, and when we did we stirred up another

troublesome brigand, and then we ceased all further speculation

in that line. I suppose that fellow that rode by on the

mule posted all the sentinels, from Athens to the Piræus,

about us.

Every field on that long route was watched by an armed

sentinel, some of whom had fallen asleep, no doubt, but were

on hand, nevertheless. This shows what sort of a country

modern Attica is—a community of questionable characters.

These men were not there to guard their possessions against

strangers, but against each other; for strangers seldom visit

Athens and the Piræus, and when they do, they go in daylight,

and can buy all the grapes they want for a trifle. The

modern inhabitants are confiscators and falsifiers of high repute,

if gossip speaks truly concerning them, and I freely

believe it does.

Just as the earliest tinges of the dawn flushed the eastern

sky and turned the pillared Parthenon to a broken harp hung

in the pearly horizon, we closed our thirteenth mile of weary,

round-about marching, and emerged upon the sea-shore abreast

the ships, with our usual escort of fifteen hundred Piræan dogs

howling at our heels. We hailed a boat that was two or three

was a police-boat on the lookout for any quarantine-breakers

that might chance to be abroad. So we dodged—we were

used to that by this time—and when the scouts reached the

spot we had so lately occupied, we were absent. They cruised

along the shore, but in the wrong direction, and shortly our

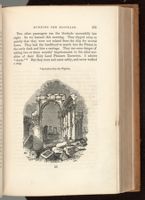

own boat issued from the gloom and took us aboard. They

had heard our

signal on the

ship. We

rowed noiselessly

away,

and before

the police-boat

came in

sight again,

we were safe

at home once

more.

Four more

of our passengers

were

anxious to

visit Athens,

and started

half an hour

after we returned;

but

they had not been ashore five minutes till the police discovered

and chased them so hotly that they barely escaped to their boat

again, and that was all. They pursued the enterprise no further.

We set sail for Constantinople to-day, but some of us little

care for that. We have seen all there was to see in the old

city that had its birth sixteen hundred years before Christ was

born, and was an old town before the foundations of Troy were

laid—and saw it in its most attractive aspect. Wherefore,

why should we worry?

Two other passengers ran the blockade successfully last

night. So we learned this morning. They slipped away so

quietly that they were not missed from the ship for several

hours. They had the hardihood to march into the Piræus in

the early dusk and hire a carriage. They ran some danger of

adding two or three months' imprisonment to the other novelties

of their Holy Land Pleasure Excursion. I admire

“cheek.”[1] But they went and came safely, and never walked

a step.

| CHAPTER XXXII. The innocents abroad, or, The new Pilgrim's

progress | ||