| | ||

A Printer's Manuscript of 1508 by W. H. Bonds

Joannes Jovianus Pontanus, the Neapolitan humanist, died in 1503, leaving a number of important unpublished works in verse and prose, and an active coterie of friends and admirers who were determined that they should be published. During his lifetime, Pontanus had been the leading spirit of the academy which took his name. After his death, the Accademia Pontaniana embarked upon an ambitious program of gathering and editing his works, a program which was to bring forth eight volumes from the press of Sigismund Mayr at Naples between 1505 and 1512, some of the texts of which eventually served as the basis for Aldus's collected edition in three volumes, 1518-1519.

The labor of preserving these works was well organized and devotedly carried out. Jacopo Sannazaro, famous as the author of Arcadia and one of Pontanus's leading disciples, assisted in collecting the texts; Francesco Puderico undertook the raising of funds to make publication possible; and Pietro Summonte assumed the editorial burden. No doubt they were also assisted by the scholarly printer, Mayr, who never failed to refer to himself in the colophons of the several books in some such terms as "singularis ingenii artifex." In order to protect the venture, Summonte secured a ten-year patent for the publication of Pontanus's works in the Kingdom of Naples, which he announced in the colophon of the first of the series in these terms: "Nequis praeter unum P. Summontium aut hoc: aut alia Ioannis Iouiani Pontani opera in tota Regni Neapolitani ditione imprimere: siue haec ipsa aliunde aduecta uendere per decennium impune queat: amplissimo priuilegio cautum est." (Parthenopei, 1505, sig. T8v).

These publications were prepared with extraordinary care, and great pains were taken to preserve the prototype manuscripts after the works were in print. Although the manuscripts were scattered during the sixteenth century, most of them survive, the greatest numbers being in the Vatican Library and at Vienna.[1] In the British Museum is preserved the

The edition is question is a well-printed folio of 94 unnumbered leaves, and its collation is a-g8 h6 i-m8. The title-page reads: PONTANI | De Prudentia : ac deinceps alii de Phi-|lofophia libri : ut per indicem qui in | calce operis eft : licet uidere.

Evidently, when typesetting began, it had been determined that De Prudentia was not to stand alone, but no decision had been reached as to what other work or works should accompany it. De Prudentia occupies quires a to h, and the remainder of the volume is taken up with the De Magnanimitate of Pontanus. The colophon to which the title refers is on sig. m8v, and it reads, "Quae toto contineantur libro: haec sunt. De Prudentia libri quinque: De Magnanimitate duo. Cum decennali priuilegio."

No date appears in the book, but Michele Tafuri, the bibliographer of Pontanus, established its date beyond reasonable doubt as 1508.[3] He showed that references in Summonte's dedications to Pontanus's Actius (1507) and De Sermone (1509) indicate that it must have appeared after the one and before the other. The situation is a little complicated by the fact that a dated octavo edition of De Prudentia was published by Filippo Giunta in Florence, also in 1508. But the Giunta edition has no direct connection with the Mayr edition. It was derived from a different manuscript and passed through the hands of a different editor. It is thus for all practical purposes totally distinct from the Mayr edition, and it needs no further consideration in the present instance.

In common with all of Mayr's editions of Pontanus, De Prudentia contains a most circumstantial explicit. It occurs on m7r, following the register, and reads, "Neapoli per Sigismundum Mayr Alemanum: singularis ingenii artificem: Ac fideliter ex archetypis: Pontani ipsius manu scriptis: quae post operum editionem: P. Summontius qua par fuit in Iouianum suum pietate: Neapoli in bibliotheca Diui Dominici seruanda collocauit."

What is known of Pontanus's library casts some light on this explicit. When Pontanus died in 1503, he was succeeded as head of the Accademia by Summonte, who at once began the pious labor of preserving the master's works from dispersal and loss. Pontanus's two daughters, Aurelia and Eugenia, seem to have placed little value on either the achievements or the library of their father. Summonte made it his first task to persuade them to turn over to him the bulk of the holograph and other manuscripts of the unpublished books, and these were to form the basis for the Accademia's editions. The transaction appears to have taken place shortly after Pontanus's death, and by it Summonte became both custodian and literary executor of the writings. In 1505 the younger daughter, Eugenia, was persuaded to present the remainder of her father's library to the church of S. Domenico in Naples. The inventory of the gift lists forty-nine volumes, and includes four of Pontanus's works, while several of the classical manuscripts were copied out in his own hand.[4] De Prudentia and De Magnanimitate do not appear in the list. Presumably they were among the manuscripts already in Summonte's safekeeping.

However that may be, the original manuscripts (or archetypi, as Summonte always called them) of the works printed between 1505 and 1512 were added by their editor to the library of S. Domenico as they appeared in print. Apparently this scheme for their preservation developed after Eugenia's gift, for there is no mention of it in the poems of 1505 or the Actius of 1507, the first two publications in the series. But most of the later volumes contain some such statement as that in De Prudentia, and it is reasonable to assume that Summonte placed all the manuscripts in S. Domenico.

But the plan for safeguarding the manuscripts and books of Pontanus was doomed to failure. In the turbulent years of the mid-sixteenth century, the library of S. Domenico was dispersed. How, when, or by whom is not known. Some volumes eventually found their way into the Vatican Library, and it is possible that they came there by way of the collection of Cardinal Guglielmo Sirleto (1504-1585). Sirleto had strong Neapolitan connections, and he began and ended his career at Rome as custodian of the Vatican Library. He was also a notable collector in his own right. At his death, his collection passed into the hands of Cardinal Ascanio Colonna, and at last into the Vatican. Several more of the manuscripts came into the possession of Joannes Sambucus, and with the rest of his extensive collection were added to the Imperial Court Library at Vienna. The manuscript of De Prudentia here under consideration contains no indication that it was

Add. MS. 12,027 is written on paper in a clear humanist hand, with some additions and revisions in the same hand, and further revisions by at least two other hands. The book is a folio, and the normal page contains twenty-three lines of text. Its gatherings are unsigned, and its collation is 1-310 414 5-1110 1212 1310, one hundred and thirty-six leaves in all; the last five leaves are blank, as are also leaves 99 and 100. Catchwords appear only on the last verso of each gathering, written downwards vertically at the foot of the inner margin. The volume is foliated in an early hand, and the old foliation runs to 138. There is a gap of two numbers following the last page of text, and it may be that the last quire once contained twelve leaves, of which the central pair is now missing.

Two leaves of a different kind of paper precede the text. These were originally end-leaves, and the verso of the first bears the inscription in an early hand, "Pontani manu opus conscriptum, et jn Actij Sinceri Bibliotheca Repertum." This inscription has been said to be in the hand of Aldus Manutius, but comparison with specimens of Aldus's autograph indicates that it is not; nor is it in the hand of the younger Aldus. A later, probably eighteenth-century, hand has added beneath this the words, "ejusque Actii Sinceri Sannazarii manu castigatum." On the facing page what appears to be the same later hand has written, "Joannis Joviani Pontani opus M. S. ad Tristanum Caracciolum et Franciscum Pudericum, de Prudentia in quinque libros distributum; repertum in Actii Sinceri Bibliotheca. Codex chartaceus manu ipsius Pontani castigatum."[6] This last inscription agrees best with the evidence supplied by the manuscript itself. There is no indication other than these three inscriptions that the book was ever in the possession of Jacopo Sannazaro,[7] whose distinctive autograph certainly does not appear anywhere in the manuscript. The text itself is not holograph, but the work of a good professional scribe. However, many of the corrections and revisions are in the hand of Pontanus, and the second revising hand was that of Summonte. In addition to the work of author and editor, the manuscript contains various markings made by the printer

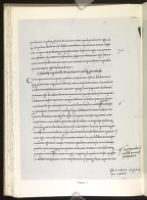

The work of the author is limited almost entirely to the rectification of scribal errors: the insertion of omitted words and phrases and, in one or two cases, lacking chapter-headings. It is impossible to determine who made many of the smaller changes of capitalization and orthography. Page 8b (fig. 1) may be taken as an example. The interpolation at the foot is undoubtedly in Pontanus's autograph, and his was probably the hand that altered "beneficitia" to "benificentia" in the last sentence preceding the heading "De Fortuna." Who corrected the q of "assqutrices" to c, capitalized the F of "Fortuna," and deleted "per" before "multa" in the penultimate line, can scarcely be determined. In any event, it is obvious that Pontanus read through the manuscript with care and attention, looking principally for places where scribal carelessness had altered his meaning.

Summonte's hand may be seen in a variety of alterations in the text and directions to the press. His editorial duties were discharged with exemplary thoroughness, and his work throughout shows that he was thinking not only of the accuracy but also of the visual effect of the publication. These two aspects of his labors are epitomized in the interesting and unusual publisher's "blurbs" which appeared on the two parts of the volume which next followed De Prudentia from Mayr's press, the De Bello Neapolitano et De Sermone of 1509. On the last verso of the first section of this book, completed in May, are the words, "Mira orthographiae ratione impressum," and on the last verso of part 2, finished in August, "Rara impressionis elegantia." Each of these phrases appears alone on its page, where it would be exposed to tempt the buyer as the unbound sheets lay in the bookseller's shop. No one can doubt what Summonte considered to be the strongest points of the publications.

Some, if not most, of the minor alterations of single letters in the text are the editor's. At least one long interpolation, that at the foot of 128b, is in his handwriting. He inserted the formal headings of Books II-V inclusive (that of the first book is in the scribe's hand), and indicated the form the headlines were to take in the printed volume. Fols. 1-11 have in his hand at the top of the versos "DE PRV." (see fig. 1) and at the top of the rectos "LIB. I." After fol. 11, he contented himself with merely writing the

Summonte was also responsible for the rectification of one major disarrangement of the text in this manuscript, where the order of certain sections of Book V was incorrect or had been revised. A large part of Book V is taken up with brief paragraphs setting forth examples of prudentia culled from the pages of history. In the manuscript, the paragraph dealing with Hostilius is followed (109b) by that concerning the Roman Senate. But the final order placed there instead the paragraph on Fabius Ambustius, which occurs in the manuscript on 112a, followed in turn by the next five sections in order, running to the middle of 118a. The new arrangement then returns to the paragraph on the Senate and runs on through the two following sections, which complete the rearrangement; the text then skips back to 118a and takes up the remaining sections to the end of the book in the order in which they appear in the manuscript. The text affected by this change appears in the published book on sigs. g5v-h1r. Summonte's method of indicating the changed order was very simple. In the margin at the beginning of each of the sections he placed an encircled capital letter, the alphabetical order showing the proper position of each in the rearrangement. (These index letters are printed without their circles in the ensuing discussion.) The section on the Senate is thus lettered G. In the margin above the G is an encircled A preceded by the section-mark, §, indicating to the compositor that he was to seek the section so marked. The section on Fabius Ambustius, of course, bears the letter A. At the end of the section F, on 118a, is the marginal note, "quaere hanc litteram G et pone omnes per ordinem usque ad I."

The short paragraphs of Book V also show an editorial policy determined and then abandoned. The manuscript as originally written set the paragraphs down without headings. Summonte then inserted all the headings, and at last, before publication, struck them all out again (see margin in fig. 3). This may have been done either to save space, or to improve the appearance. A number of the sections occupy no more than two lines of type. Section-headings for all would have swelled the size of the book, and would also have given it a choppy and cut-up look.

Besides the disarrangement in Book V, the text of the manuscript is seriously defective at two points: it lacks the prologues to Books IV and V. These were evidently supplied for the printed book from another manuscript. At the head of Book IV (82b) is drawn a long acute angle enclosing an encircled dot, to indicate an insertion. At the head of Book V (101a) is a more complicated signal, consisting of two concentric circles cut by a vertical

The altered decision on the section-headings of Book V and the estimate of the length of its prologue reflect a concern for the physical appearance of the printed book which is to be seen even more clearly in a series of directions to the printer which runs through the whole manuscript. Summonte wrote most of these on small slips of paper or labels inserted at the appropriate points; a few were simply written in the margins. They represent what must be one of the earliest attempts at book-design by a person outside the staff of the printing-office, and as such they are extraordinarily interesting.

The simplest of the directions relate to the oblong space six lines deep containing only a guide-letter, which occurs at the beginning of each prologue and book in the printed work, intended for the insertion of an illuminated or pen-work initial. On fol. 4a is the first of these, a label which reads, "Spatium pro Tonsa, secundum primum." (See fig. 4.) This is at the beginning of the text of the main part of Book I; if any direction was inserted for the beginning of the prologue, it has disappeared. At any rate, the printer was ordered to leave a space for the initial just as he had the first time. At the beginning of the prologue to Book II is simply the word "tonsa" in the margin, while at the head of the main text of Book II is the notation, "Tonsa come la prima." Thereafter only the word "tonsa" is used.[10]

A second class of direction relates to the insertion of additional chapter-headings, which were written in by Summonte. Where space permitted, he inserted them in the text as they would normally have appeared; where there was not enough space, he indicated their proper point of insertion in the text with a gallows-like paragraph mark, repeated in the margin with the heading following it. The label pasted at the foot of fol. 72a (fig. 2) is the earliest and most detailed of the directions dealing with this circumstance: "Questa é rubrica et pero farite qua capitulo."[11] Simpler labels to this effect were pasted on fols. 73a and 73b, after which a number of insertions were permitted to pass without comment; but when another insertion was made somewhat later, Summonte felt it wise to be specific again, and a label on fol. 122a reads, "fate capitulo et cosi farete in li altri conveneno appresso" (fig. 3).

Even more directly concerned with the design are the labels intended by Summonte to indicate differences in layout between manuscript and printed book. In the manuscript the prologue to Book II ends with a blank space of nearly half a page; here Summonte wrote, "vna riga vacua in mezo." Unfortunately in this case good typography forbade the following of the instruction, for the prologue ended only seven lines short of a full page (sig. c4r). Leaving one line blank would have allowed only the six lines necessary for the "tonsa" at the beginning of the main text of Book II, with a totally unacceptable visual effect. Very wisely Summonte's direction was countermanded or ignored; the manuscript contains no further mark to indicate which.

But Summonte's other instructions of this kind were carried out as nearly as possible by the printer. The last section of Book II has no heading, and in the manuscript (fol. 56a) it is set off from the preceding section by a blank line. Summonte inserted a label reading, "la ultima riga sia meza o poco piu ó manco di meza / et lo capitulo che seguita non habia da sú riga vacua ma siano continuate le righe." In the printed book (sig. d3v), the preceding section ends with a little more than half a line of type. The last section follows immediately in the next line, only being indicated in the usual fashion by having its initial letter set out in the left margin. Very similar labels appear in similar circumstances on fols. 69a and 122a (fig. 3), and both are likewise carried out in print. Finally, on fols. 100b and 130b appear instructions to leave a blank line in the text, also carried out in print.

Summonte's attentions to the manuscript thus ranged from the purely textual to the purely typographical, and his concern is clearly perceptible

The marks made in the manuscript by the printer were, as one might expect, on a severely practical level. First of all, he cast off the copy to determine how many pages of print it would occupy. Probably by experiment he found that forty-nine lines of manuscript produced about one page (forty-two lines) of printing; so one of his first acts was to mark the manuscript every seventh line, that being the common denominator of these two figures. Some of this marking was done in pencil, but most with a very light pen-stroke, usually in the left margin. The entire manuscript, with very few exceptions, was so marked; in a few instances, the unit of measurement was eight lines, but these seem to represent mistakes. The rubricated section-headings were counted as normal lines.

The manuscript was also marked to show the division into pages of type. The exact point where it was divided was indicated within the line by the step-like mark of division commonly used by printers, and in the margin was written the number of the page within the particular quire which began at that point. Thus, the beginning of the text of sig. d1r in the printed book is marked in the manuscript, "D.pa.1."; d1v is marked "2"; d2r is "3"; and so on. The signature-letter is given for only the first page of each quire.

Some of these marks appear to represent experimental casting-off or else trial settings, where as many as three divisions appear for each page. In these cases, all but the mark for the eventual division are deleted by crossing out. In fig. 2, the cancelled division-mark is opposite the numeral 6; the true division-mark is about a line later, a smaller T-shaped mark. In the printed book this is the division between e3r and e3v (the beginning of the sixth page of quire e).

Lightly but crudely pencilled numerals appear in the margins against the section headings in the first dozen leaves of the manuscript. The number 25 preceding "De Fortuna" in fig. 1 is an example. These relate to one series of the cancelled division-marks, and indicate the number of lines of

One other mark appears in the manuscript, and it very probably has nothing to do with either the editing or the printing of it. This is the word "breue" which appears nine times in the margins of Book V, in a hand which I cannot identify. There is no unusual effort at compression of text in either manuscript or printed book at these points, and there seems to be no ready explanation of the appearance of the word there. Possibly it is an indication by some unknown reader of the manuscript that certain portions of the text were to be summarized for his notes.

The printed text contains, in fact, more abbreviations throughout than the manuscript, and within the printed book the amount of abbreviation varies widely from page to page; in some portions there are only one or two abbreviations to the line, in others as many as five or six to the line. It is evident that as usual the compositor followed his own whim and the requirements of justification in employing abbreviations; there is no observable relation to the manuscript in this respect. Otherwise, he followed the manuscript very faithfully, regarding in particular the changes in orthography and capitalization which had been made in it. He also followed its punctuation exactly, with one major change. The most common mark of punctuation in the manuscript was the slant or virgule, and this apparently was not in his roman fount, so it is everywhere replaced by the colon—not, perhaps, a happy choice, as it tends to break up the type-page.

We have, then, in the British Museum manuscript of De Prudentia, a good example of scholarly editor and scholarly printer working harmoniously together to produce an edition not only meticulously edited but also carefully designed—certainly a very early instance of such a partnership.

Notes

See the introduction by Benedetto Soldati to his edition of Ioannis Ioviani Pontani Carmina (Firenze, 1902), I, ix-xxxiii; and Erasmo Percopo, "La Biblioteca di Gioviano Pontano," In Onore di Giovanni Gioviano Pontano, L'Accademia Pontaniana (Naples, 1926), pp. 53-65.

I am indebted to Mr. T. J. Brown, of the Department of Manuscripts, British Museum, for calling the manuscript to my attention. I have also to acknowledge the permission of the Trustees of the British Museum to reproduce four pages of the MS. as illustrations of this study.

The glory of Pontanus's library had been the great Vatican Virgil; but this had passed into Pietro Bembo's possession on the way to its eventual destination some years before Pontanus's death.

Actius Sincerus was the sobriquet bestowed on Sannazaro by Pontanus, in accordance with the custom of the Accademia. Thus Pontanus had also given himself a middle name, Jovianus.

Bound in at the beginning of Add. MS. 12,027 is a modern manuscript in French containing fourteen leaves (two are blank), signed "E. Audin" and dated "Florence, 30 November 1821." In it Audin discusses the manuscript and attempts to relate it to the printed editions known to him. Unfortunately, the undated edition actually printed from the manuscript was not among these, and consequently much of Audin's speculation is without foundation.

Similar markings are used at several other points in the manuscript to indicate shorter insertions.

Tonsa is an abbreviation for littera tonsa (lettera tonda, lettre tondue). In the thirteenth century litterae tonsae meant a perpendicular and elongated alphabet, derived in part from capitals and uncials and in part from minuscules, used for the headings of papal bulls and to signalize letters or words supplied in copies of earlier documents to fill lacunae; see L. Delisle, "Les 'Litterae Tonsae' à la Chancellerie romaine au XIIIe Siècle," Bibliothèque de l'École des Chartes, LXII (1901), 256-263. I am indebted to Mr. Stanley Morison for this reference. But to the humanist scribes and their followers, litterae tonsae came to mean the upright roman script as differentiated from the cursive. Thus at the end of the sixteenth century the writing-master Marc'Antonio Rossi (Giardino de Scrittore, Rome, 1598) explains that his lettera antica tonda derives from the ancient Roman majuscule (plate 80), and proceeds to give nine plates of specimens of various sizes. Evidently the phrase meant the same a century earlier, and Summonte's direction referred to a roman capital to be inserted in the manner customary in early books.

| | ||