5. CHAPTER V.

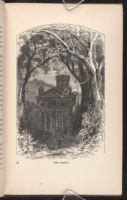

AT THE CASTLE.

By the time August reached Andrew Anderson's

castle it was dark. The castle was built in

a hollow, looking out toward the Ohio River, a

river that has this peculiarity, that it is all beautiful,

from Pittsburgh to Cairo. Through the trees,

on which the buds were just bursting, August looked out on the

golden roadway made by the moonbeams on the river. And

into the tumult of his feelings there came the sweet benediction

of Nature. And what is Nature but the voice of God?

Anderson's castle was a large log building of strange construction.

Everything about it had been built by the hands of

Andrew, at once its lord and its architect. Evidently a whimsical

fancy had pleased itself in the construction. It was an

attempt to realize something of medieval form in logs. There

were buttresses and antique windows, and by an ingenious transformation

the chimney, usually such a disfigurement to a loghouse,

was made to look like a round donjon keep. But it was

strangely composite, and I am afraid Mr. Ruskin would have

considered it somewhat confused; for while it looked like a

rude castle to those who approached it from the hills, it looked

like something very different to those who approached the

front, for upon that side was a portico with massive Doric

columns, which were nothing more nor less than maple logs.

Andrew maintained that the natural form of the trunk of a tree

was the ideal and perfect form of a pillar.

To this picturesque structure, half castle, half cabin, with

hints of church and temple, came August Wehle on Saturday

evening. He did not go round to the portico and knock at the

front-door as a stranger would have done, but in behind the

donjon chimney he pulled an alarm-cord. Immediately the

head of Andrew Anderson was thrust out of a Gothic hole—

you could not call it a window. His uncut hair, rather darker

than auburn, fell down to his waist, and his shaggy red beard

lay upon his bosom. Instead of a coat he wore that unique garment

of linsey-woolsey known in the West as wa'mus (warm

us?), a sort of over-shirt. He was forty-five, but there were

streaks of gray in his hair and beard, and he looked older by

ten years.

“What ho, good friend? Is that you?” he cried. “Come

up, and right welcome!” For his language was as archaic and

perhaps as incongruous as his architecture. And then throwing

out of the window a rope-ladder, he called out again, “Ascend!

ascend! my brave young friend!”

And young Wehle climbed up the ladder into the large upper

room. For it was one peculiarity of the castle that the upper

part had no visible communication with the lower. Except

August, and now and then a literary stranger, no one but the

owner was ever admitted to the upper story of the house, and

the neighbors, who always had access to the lower rooms, re

[ILLUSTRATION]

THE CASTLE.

[Description: 555EAF. Page 041. Illustration page. Engraving with arched top of stone building

with a tower or turret in the woods. A small figure approaches in the foreground.]

garded the upper part of the castle with mysterious awe.

August was often plied with questions about it, but he always

answered simply that he didn't think Mr. Anderson would like

to have it talked about. For the owner there must have been

some inside mode of access to the second story, but he did

not choose to let even August know of any other way than

that by the rope-ladder, and the few strangers who came to see

his books were taken in by the same drawbridge.

The room was filled with books arranged after whimsical

associations. One set of cases, for instance, was called the

Academy, and into these he only admitted the masters, following

the guidance of his own eccentric judgment quite as much

as he followed traditional estimate. Homer, Virgil, Dante, and

Milton of course had undisputed possession of the department

devoted to the “Kings of Epic,” as he styled them. Sophocles,

Calderon, Corneille, and Shakespeare were all that he admitted

to his list of “Kings of Tragedy.” Lope he rejected on literary

grounds, and Goethe because he thought his moral tendency

bad. He rejected Rabelais from his chief humorists, but accepted

Cervantes, Le Sage, Molière, Swift, Hood, and the then

fresh Pickwick of Boz. To these he added the Georgia Scenes

of Mr. Longstreet, insisting that they were quite equal to Don

Quixote. I can only stop to mention one other department in

his Academy. One case was devoted to the “Best Stories,” and

an admirable set they were! I wish that anything of mine

were worthy to go into such company. His purity of feeling,

almost ascetic, led him to reject Boccaccio, but he admitted

Chaucer and some of Balzac's, and Smollett, Goldsmith, and

De Foe, and Walter Scott's best, Irving's Rip Van Winkle, Bernardin

St. Pierre's “Paul and Virginia,” and “Three Months

under the Snow,” and Charles Lamb's generally overlooked

“Rosamund Gray.” There were cases for “Socrates and his

Friends,” and for other classes. He had amused himself for

years in deciding what books should be “crowned,” as he called

it, and what not. And then he had another case, called “The

Inferno.” I wish there was space to give a list of this department.

Some were damned for dullness and some for coarseness.

Miss Edgeworth's Moral Tales, Darwin's Botanic Garden,

Rollin's Ancient History, and a hideously illustrated copy of

the Book of Martyrs were in the first-class, Don Juan and some

French novels in the second. Tupper, Swinburne, and Walt

Whitman he did not know.

In the corner next the donjon chimney was a little room

with a small fireplace. Thus the hermit economized wood, for

wood meant time, and time meant communion with his books.

All of his domestic arrangements were carried on after this frugal

fashion. In the little room was a writing-desk, covered with

manuscripts and commonplace books.

“Well, my young friend, you're thrice welcome,” said Andrew,

who never dropped his book language. “What will you have?

Will you resume your apprenticeship under Goethe, or shall we

canter to Canterbury with Chaucer? Grand old Dan Chaucer!

Or, shall we study magical philosophy with Roger Bacon—the

Friar, the Admirable Doctor? or read good Sir Thomas More?

What would Sir Thomas have said if he could have thought that

he would be admired by two such people as you and I, in the

woods of America, in the nineteenth century? But you do not

want books! Ah! my brave friend, you are not well. Come

into my cell and let us talk. What grieves you?”

And Andrew took him by the hand with the courtesy of a

knight, with the tenderness of a woman, and with the air of an

astrologer, and led him into the apartment of a monk.

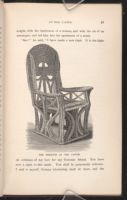

“See!” he said, “I have made a new chair. It is the highest

evidence of my love for my Teutonic friend. You have

now a right to this castle. You shall be perpetually welcome.

I said to myself, German scholarship shall sit there, and the

Backwoods Philosopher will sit here. So sit down on my

sedilium, and let us hear how this uncivil and inconstant world

treats you. It can not deal worse with you than it has with me.

But I have had my revenge on it! I have been revenged! I

have done as I pleased, and defied the world and all its hollow

conventionalities.” These last words were spoken in a tone of

misanthropic bitterness common to Andrew. His love for

August was the more intense that it stood upon a background

of general dislike, if not for the world, at least for that portion

of it which most immediately surrounded him.

August took the chair, ingeniously woven and built of rye

straw and hickory splints. He knew that all this formality and

apparent pedantry was superficial. He and Andrew were bosom

friends, and as he had often opened his heart to the master of

the castle before, so now he had no difficulty in telling him his

troubles, scarcely heeding the appropriate quotations which Andrew

made from time to time by way of embellishment.