23. CHAPTER XXIII.

IF there is any life that is happier than the life we led on our

timber ranch for the next two or three weeks, it must be

a sort of life which I have not read of in books or experienced

in person. We did not see a human being but ourselves during

the time, or hear any sounds but those that were made by the

wind and the waves, the sighing of the pines, and now and

then the far-off thunder of an avalanche. The forest about us

was dense and cool, the sky above us was cloudless and brilliant

with sunshine, the broad lake before us was glassy and

clear, or rippled and breezy, or black and storm-tossed, according

to Nature's mood; and its circling border of mountain

domes, clothed with forests, scarred with land-slides, cloven by

canons and valleys, and helmeted with glittering snow, fitly

framed and finished the noble picture. The view was always

fascinating, bewitching, entrancing. The eye was never tired

of gazing, night or day, in calm or storm; it suffered but one

grief, and that was that it could not look always, but must close

sometimes in sleep.

We slept in the sand close to the water's edge, between two

protecting boulders, which took care of the stormy night-winds

for us. We never took any paregoric to make us sleep. At

the first break of dawn we were always up and running footraces

to tone down excess of physical vigor and exuberance of

spirits. That is, Johnny was—but I held his hat. While

smoking the pipe of peace after breakfast we watched the sentinel

peaks put on the glory of the sun, and followed the conquering

[ILLUSTRATION]

AT BUSINESS.

[Description: 504EAF. Page 174. In-line image of two men sitting in a row boat at night.

They are seated low in the boat and are looking around.]

light as it swept down among the shadows, and set the

captive crags and forests free. We watched the tinted pictures

grow and brighten upon the water till every little detail of

forest, precipice and pinnacle was wrought in and finished, and

the miracle of the enchanter complete. Then to “business.”

That is, drifting around in the boat. We were on the

north shore. There, the rocks on the bottom are sometimes

gray, sometimes white.

This gives the marvelous

transparency of the water

a fuller advantage than it

has elsewhere on the lake.

We usually pushed out a

hundred yards or so from

shore, and then lay down

on the thwarts, in the

sun, and let the boat

drift by the hour whither it would. We

seldom talked. It interrupted the Sabbath

stillness, and marred the dreams the luxurious

rest and indolence brought. The shore

all along was indented with deep, curved bays and coves,

bordered by narrow sand-beaches; and where the sand ended,

the steep mountain-sides rose right up aloft into space—rose

up like a vast wall a little out of the perpendicular, and

thickly wooded with tall pines.

So singularly clear was the water, that where it was only

twenty or thirty feet deep the bottom was so perfectly distinct

that the boat seemed floating in the air! Yes, where it was

even eighty feet deep. Every little pebble was distinct, every

speckled trout, every hand's-breadth of sand. Often, as we lay

on our faces, a granite boulder, as large as a village church,

would start out of the bottom apparently, and seem climbing

up rapidly to the surface, till presently it threatened to touch

our faces, and we could not resist the impulse to seize an oar

and avert the danger. But the boat would float on, and the

boulder descend again, and then we could see that when we

had been exactly above it, it must still have been twenty or

thirty feet below the surface. Down through the transparency

of these great depths, the water was not

merely transparent,

but dazzlingly, brilliantly so. All objects seen through it had

a bright, strong vividness, not only of outline, but of every

minute detail, which they would not have had when seen

simply through the same depth of atmosphere. So empty and

airy did all spaces seem below us, and so strong was the sense

of floating high aloft in mid-nothingness, that we called these

boat-excursions “balloon-voyages.”

We fished a good deal, but we did not average one fish a

week. We could see trout by the thousand winging about in

the emptiness under us, or sleeping in shoals on the bottom, but

they would not bite—they could see the line too plainly, perhaps.

We frequently selected the trout we wanted, and rested

the bait patiently and persistently on the end of his nose at a

depth of eighty feet, but he would only shake it off with an

annoyed manner, and shift his position.

We bathed occasionally, but the water was rather chilly, for

all it looked so sunny. Sometimes we rowed out to the “blue

water,” a mile or two from shore. It was as dead blue as indigo

there, because of the immense depth. By official measurement

the lake in its centre is one thousand five hundred and

twenty-five feet deep!

Sometimes, on lazy afternoons, we lolled on the sand in

camp, and smoked pipes and read some old well-worn novels.

At night, by the camp-fire, we played euchre and seven-up to

strengthen the mind—and played them with cards so greasy

and defaced that only a whole summer's acquaintance with

them could enable the student to tell the ace of clubs from the

jack of diamonds.

We never slept in our “house.” It never recurred to us,

for one thing; and besides, it was built to hold the ground,

and that was enough. We did not wish to strain it.

By and by our provisions began to run short, and we

went back to the old camp and laid in a new supply. We

were gone all day, and reached home again about night-fall,

pretty tired and hungry. While Johnny was carrying the

main bulk of the provisions up to our “house” for future use,

I took the loaf of bread, some slices of bacon, and the coffee-pot,

ashore, set them down by a tree, lit a fire, and went back to the

boat to get the frying-pan. While I was at this, I heard a

shout from Johnny, and looking up I saw that my fire was

galloping all over the premises!

Johnny was on the other side of it. He had to run through

the flames to get to the lake shore, and then we stood helpless

and watched the devastation.

The ground was deeply carpeted with dry pine-needles, and

the fire touched them off as if they were gunpowder. It was

wonderful to see with what fierce speed the tall sheet of flame

traveled! My coffee-pot was gone, and everything with it.

In a minute and a half the fire seized upon a dense growth of

dry manzanita chapparal six or eight feet high, and then the

roaring and popping and crackling was something terrific. We

were driven to the boat by the intense heat, and there we remained,

spell-bound.

Within half an hour all before us was a tossing, blinding

tempest of flame! It went surging up adjacent ridges—surmounted

them and disappeared in the cañons beyond—burst

into view upon higher and farther ridges, presently—shed a

grander illumination abroad, and dove again—flamed out again,

directly, higher and still higher up the mountain-side—threw

out skirmishing parties of fire here and there, and sent them

trailing their crimson spirals away among remote ramparts

and ribs and gorges, till as far as the eye could reach the lofty

mountain-fronts were webbed as it were with a tangled net-work

of red lava streams. Away across the water the crags

and domes were lit with a ruddy glare, and the firmament above

was a reflected hell!

Every feature of the spectacle was repeated in the glowing

mirror of the lake! Both pictures were sublime, both were

beautiful; but that in the lake had a bewildering richness about it

that enchanted the eye and held it with the stronger fascination.

We sat absorbed and motionless through four long hours.

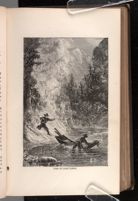

[ILLUSTRATION]

FIRE AT LAKE TAHOE.

[Description: 504EAF. Illustration page containing a man in a boat, and another man jumping

from the shore into the boat. In the background there are high trees and smoke.]

We never thought of supper, and never felt fatigue. But at

eleven o'clock the conflagration had traveled beyond our range

of vision, and then darkness stole down upon the landscape

again.

Hunger asserted itself now, but there was nothing to eat.

The provisions were all cooked, no doubt, but we did not go

to see. We were homeless wanderers again, without any property.

Our fence was gone, our house burned down; no insurance.

Our pine forest was well scorched, the dead trees all

burned up, and our broad acres of manzanita swept away.

Our blankets were on our usual sand-bed, however, and so we

lay down and went to sleep. The next morning we started

back to the old camp, but while out a long way from shore, so

great a storm came up that we dared not try to land. So I

baled out the seas we shipped, and Johnny pulled heavily

through the billows till we had reached a point three or four

miles beyond the camp. The storm was increasing, and it became

evident that it was better to take the hazard of beaching

the boat than go down in a hundred fathoms of water; so we

ran in, with tall white-caps following, and I sat down in the

stern-sheets and pointed her head-on to the shore. The instant

the bow struck, a wave came over the stern that washed crew

and cargo ashore, and saved a deal of trouble. We shivered

in the lee of a boulder all the rest of the day, and froze all

the night through. In the morning the tempest had gone

down, and we paddled down to the camp without any unnecessary

delay. We were so starved that we ate up the rest of the

Brigade's provisions, and then set out to Carson to tell them

about it and ask their forgiveness. It was accorded, upon

payment of damages.

We made many trips to the lake after that, and had many

a hair-breadth escape and blood-curdling adventure which will

never be recorded in any history.